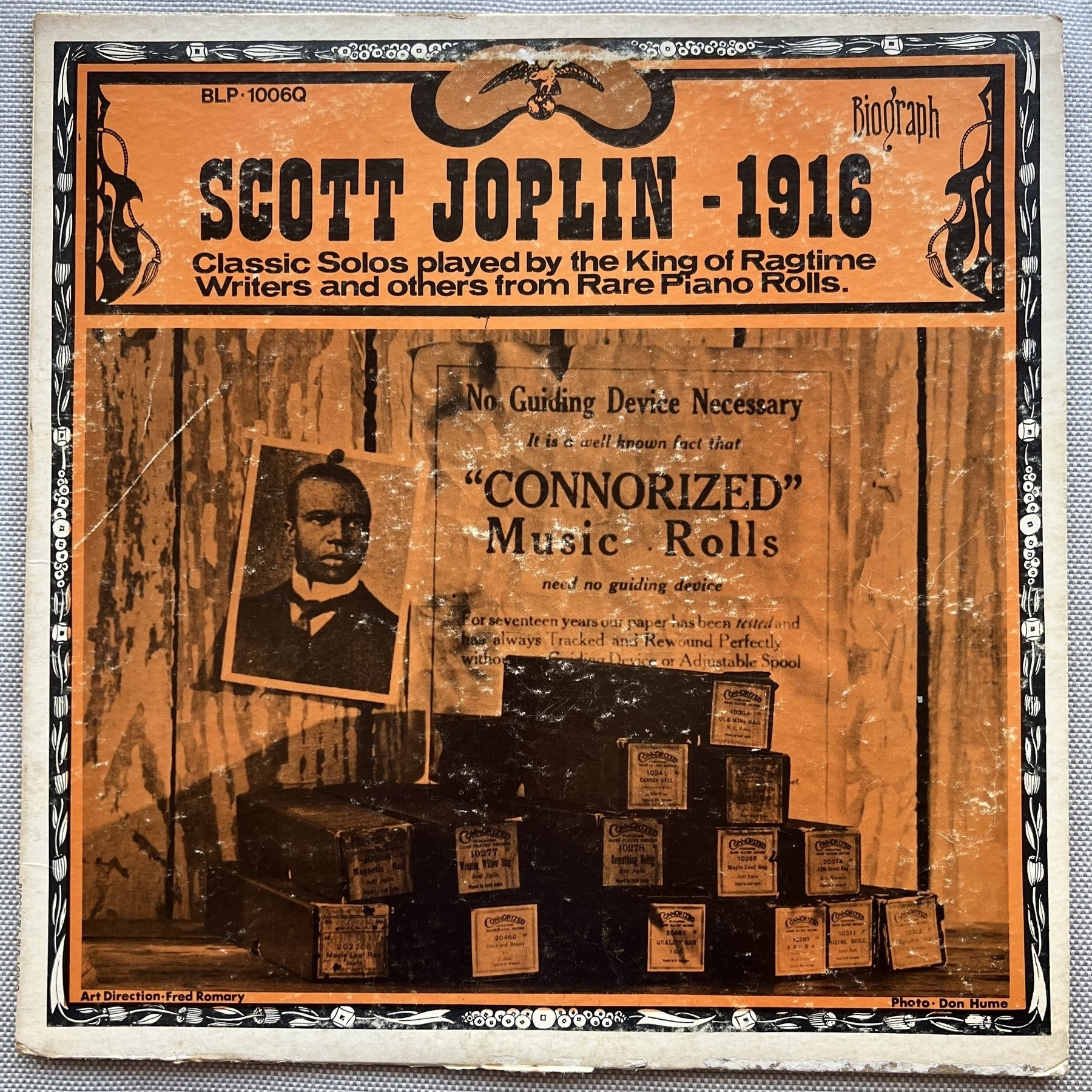

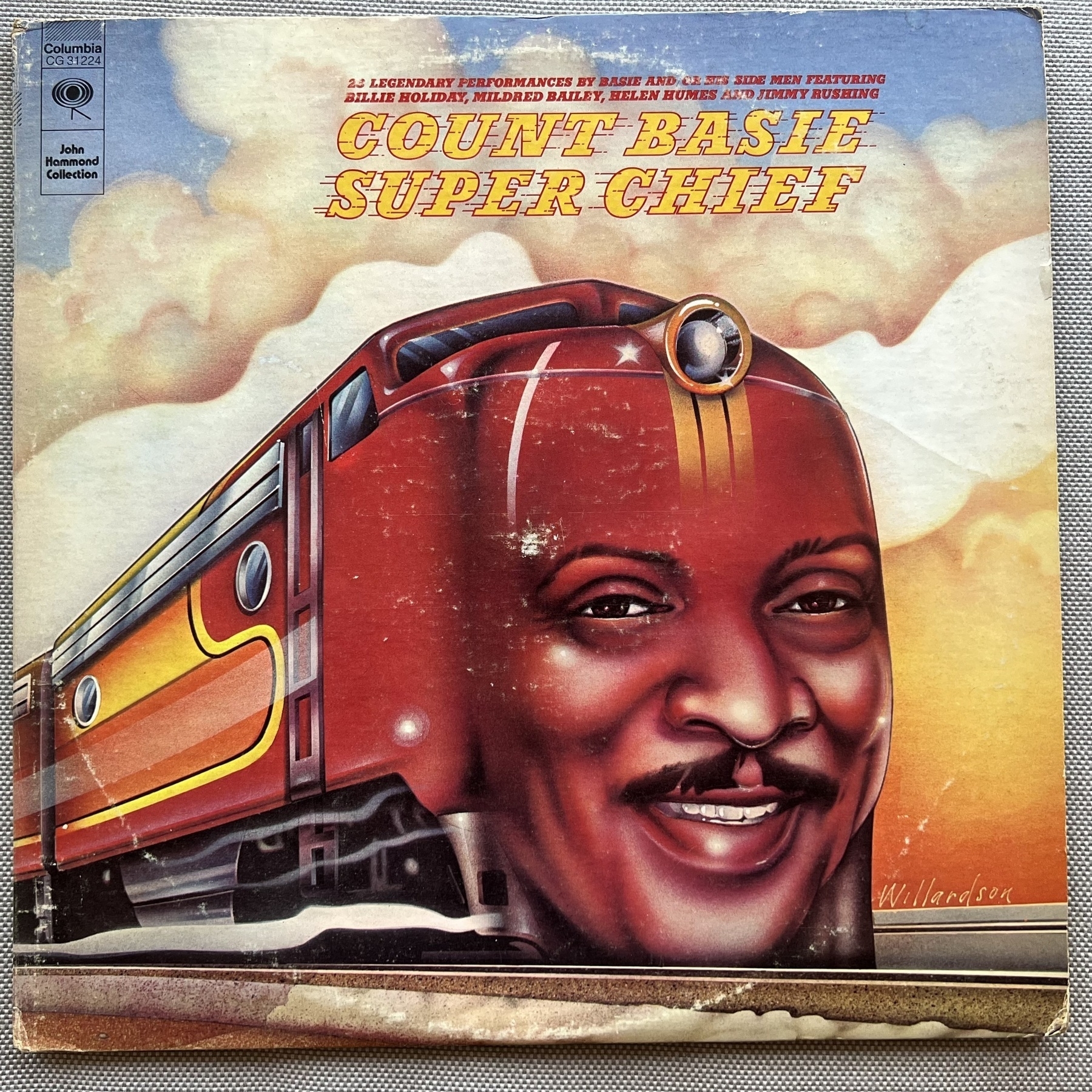

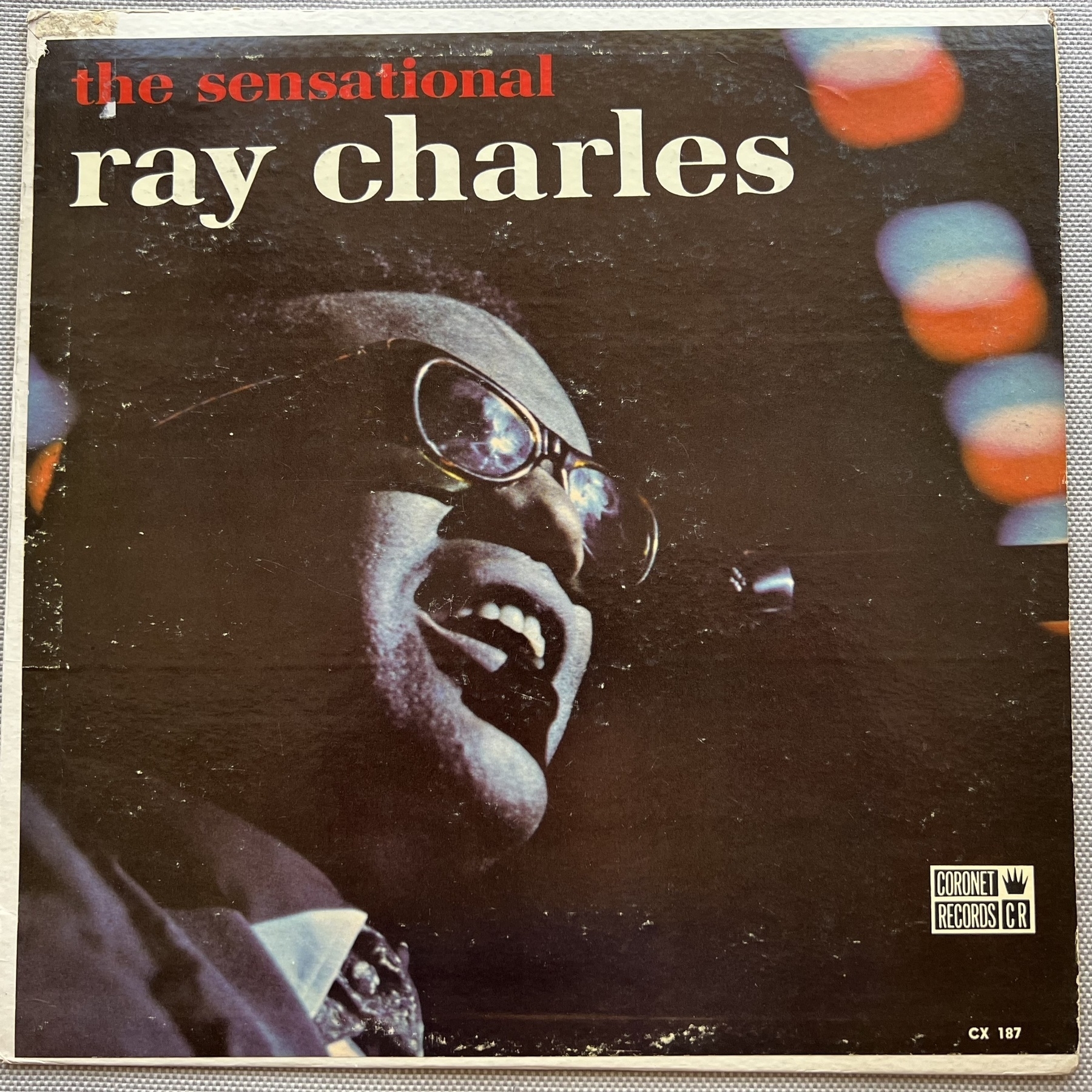

Hit up some used-record stores in Austin today – all these from the 3-dollar bins!

Gary Saul Morson: “The Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation, published 50 years ago, was much more than a detailed account compiled from the testimonies of hundreds of people; it was also arguably the 20th century’s greatest piece of nonfiction prose." At the moment I’m thinking that its primary competition for that title is Rebecca West’s Black Lamb and Grey Falcon and Claude Levi-Strauss’s Tristes Tropiques.

I read and annotated that new Tara Isabella Burton essay on postrationalism in Silicon Valley.

From William James’s speech at the dedication of a memorial in Boston to a soldier named Robert Gould Shaw (1887):

The deadliest enemies of nations are not their foreign foes; they always dwell within their borders. And from these internal enemies civilization is always in need of being saved. The nation blest above all nations is she in whom the civic genius of the people does the saving day by day, by acts without external picturesqueness; by speaking, writing, voting reasonably; by smiting corruption swiftly; by good temper between parties; by the people knowing true men when they see them, and preferring them as leaders to rabid partisans or empty quacks. Such nations have no need of wars to save them. Their accounts with righteousness are always even; and God’s judgments do not have to overtake them fitfully in bloody spasms and convulsions of the race.

Currently reading: The Metaphysical Club by Louis Menand 📚

Finished reading: Richard Hofstadter: Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, The Paranoid Style in American Politics, Uncollected Essays 1956-1965 (LOA #330) by Richard Hofstadter. Eerily relevant to our moment. 📚

Tara Isabella Burton’s essay about post-rationalism in Silicon Valley is a vital read.

Elon Musk, self-proclaimed “free-speech absolutist,” is happily cooperating with the Turkish government’s silencing of its political opponents. Cool.

I wrote about the Three Paths of micro.blog.

the three paths of micro.blog

I’ve written here from time to time about the excellent service known as micro.blog — and I still want to commend it to those of you who have had enough of the big social-media platforms. You have to pay for it, but you get a lot for your money, including freedom from advertising.

Micro.blog is a highly flexible service with many intriguing features, and it may be hard for new users to decide just which ones are most useful for them. Perhaps it would help if you think of micro.blog as offering three different (though overlapping) paths, and spend some time considering which path best meets your needs.

Path One: Community. For many users, micro.blog is a smallish community of like-minded people — a place to connect with interesting folks, in a much more low-key and undramatic way than what places like Facebook and Twitter (and even Mastodon) offer. If you go to the Discover page you’ll find something that looks like this:

That’s a great way to find people who share your interests.

Path Two: Blog. Micro.blog is also a great blogging platform. It was, as its name suggests, originally designed for small posts, but it scales up to posts of any size. When your post gets longer than 300 characters, you get the option to add a title to the post; then people looking at your timeline will see that title as a link, which they can click on to see the full post. Micro.blog also offers categories that you can use to organize different kinds of posts. Basically, it can replace any of the cruftier and less agile blog platforms, like WordPress — but it has a much more streamlined and elegant UI for posting. Best of both worlds, I think. (For longer posts, like this one, I still use the WordPress-powered blog you’re reading, because I have 15 years of tags here, but for everything else I use micro.blog because it provides such a comfortable environment for writing.)

Path Three: Journal. This has become my primary way to use micro.blog. I mainly post (a) photos, (b) links to what I’ve been reading — micro.blog is definitively the best blogging platform for readers — and listening to, and (c) the occasional brief audio post (AKA microcast). It’s a great way for me to share what I’m up to for folks who may be interested — but also, and for me primarily, to keep a kind of life journal.

Here’s the key takeaway for you: Micro.blog is equally useful for each of these paths. So if you start out using it just for blogging but then decide you want more of an interactive community, you can shift in that direction. It will accommodate your needs. Now, as I have said before, it will — by design — never be a place for you to monetize your brand, troll, shitpost, or become an influencer. But hey, there are plenty of other platforms better suited for that kind of thing. Micro.blog is better suited for the more human and humane paths I have identified here.

Currently listening: Ry Cooder - Jazz. One of my all-time favorites. ♫

Jenny Odell: “I felt like I needed to protect my time more so that I could do things that I wanted, and it obscured the fact that what I wanted was a sense of connection and meaning, and in order to get that I would have to do something that looked like giving my time away. Since you mentioned kids: A couple of weeks ago, I was hanging out with a friend who has a 3-year-old, and it took us half an hour to walk two blocks. There is a way in which … you could view that experience as potentially boring, but you could also see that the reason we were walking slowly is that kids are looking at stuff in a weird way!”

Augustine, De Trinitate I.iii.5: “Dear reader, whenever you are certain about something as I am go forward with me; whenever you hesitate, seek with me; whenever you discover that you have gone wrong come back to me; or if I have gone wrong, call me back to you. In this way we will travel along the street of love together as we make our way toward Him of whom it is said, ‘Seek His face always.’”

People say Arsenal couldn’t handle the intensity of a title challenge, and while there’s probably some truth to that, I think the far bigger issue is: They got tired. They don’t have City’s depth, and their best players just wore down over the last month. ⚽️

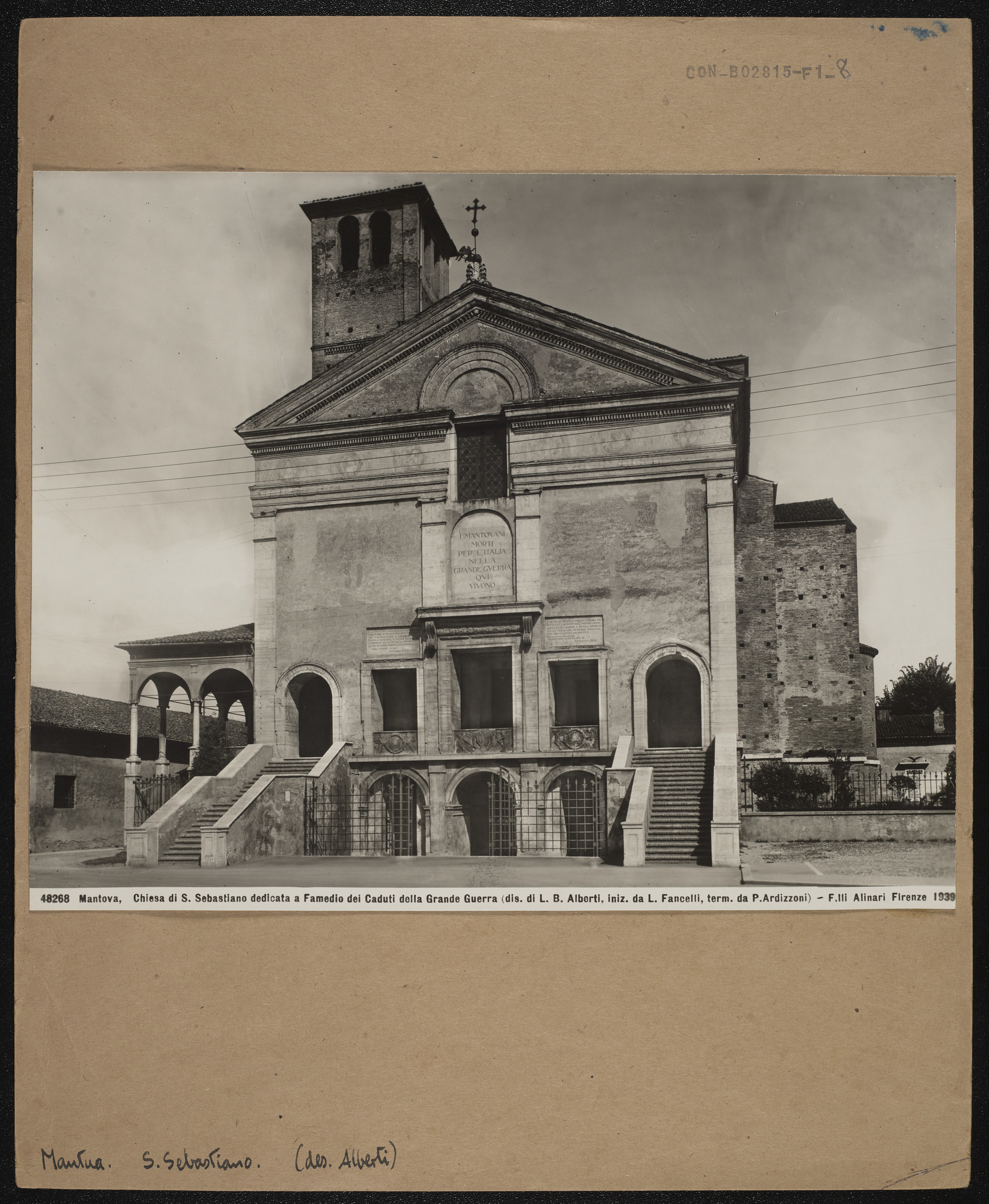

From the remarkable collection of photographs at the Courtauld Institute.

Currently reading: Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, The Paranoid Style in American Politics, Uncollected Essays 1956-1965 by Richard Hofstadter 📚