A fascinating look at the etymology of the Greek word doulos — “slave.” The cognates are remarkable.

I don’t think I appreciated how much a democracy depends upon regular people standing up to defend their rights and their powers against the elites who try to usurp them. These days people are happy to give up their rights and power if they can find some strongman or strongwoman willing to take it. This is a much larger part of human nature than I thought.

The tech media is largely failing to tell this story, so I’ll mark the moment: fall 2025 is when the new Luddite movement really began to accelerate. For the first time in a long time, there is palpable energy – positive energy – in tech. It’s directed away from the Big Tech companies, and toward alternative platforms and mindsets. Many people are trying to opt out of Big Tech altogether.

Come with me! Come with me to FREEDOM!

The Most Revd Dr Laurent Mbanda, Chairman, Gafcon Primates’ Council: “As has been the case from the very beginning, we have not left the Anglican Communion; we are the Anglican Communion.”

Finished reading: Shadow Ticket by Thomas Pynchon. I’m not yet ready to do a review — that will have to wait for a second reading — but I will say that the people who see this as the third in a detective trilogy, following Inherent Vice (2009) and Bleeding Edge (2013), are mostly wrong. The essential point of this book is to trace a line that links the multiple timelines of Against the Day (2006) to the next-door-to-ours hippiecentric moral universe of Vineland (1990) — a connection made pretty explicit when in the final chapter we see a U-boat (“an encapsulated volume of pre-Fascist space-time”) that travels through an alternate dimension in just the way that the Chums of Chance travel in Against, and then read a letter from Skeet Wheeler, on his way to California, quite obviously the father of Vineland’s Zoyd Wheeler. This alternate history of our world runs from the Chicago World’s Fair to the Tunguska Event to Prohibition to the rise of European fascism and ultimately to Reagan’s America. But passage from one terminus to the other takes us through what the narrator of Mason & Dixon (1997) calls “Worlds alternative to this one” — which is why you need a shadow ticket. 📚

The hype is expected — new tech runs on speculation. You can feel the residue of the last 30 years of booms. There is a sense that people missed their chance to get rich on the internet, on ecommerce, on the app store, on social media, on crypto, on meme stocks, on NVIDIA. The hype bubbles get inflated because individuals don’t want to miss their chance at another windfall, and companies don’t want to get displaced by any nascent technological shifts. The history of tech has calcified into stories of dramatic wins and unforeseen downfalls, and what results is a tech culture of near compulsory participation in prediction rather than creating value or serving needs.

The whole talk is great.

Dan Cohen is officially my hero:

I have begun adding art museum [Model Context Protocols] to my custom rig in Claude, including connectors to the collections of the Met and the Art Institute of Chicago. With the article databases our team has attached to Claude through our MCP server, my test setup has reached a level of comprehensiveness that enables me to turn off web retrieval (RAG) entirely, and I now can rely solely on library- and museum-augmented responses. The results are very promising. When I ask about “Cubism,” for instance, instead of web-based regurgitation, Claude returns a good array of articles on Cubism, as well as representative artwork that has been digitized by museums and related curatorial text.

Learn more about Model Context Protocols here. @dancohen is my hero because he is not accepting the defaults imposed the AI megafauna but instead is engaged in an imaginative critical filtering that is, IMO, paving the way for how smart university leaders could leverage LLMs for legitimate educational purposes — instead of just trying to obey and please Sam Altman.

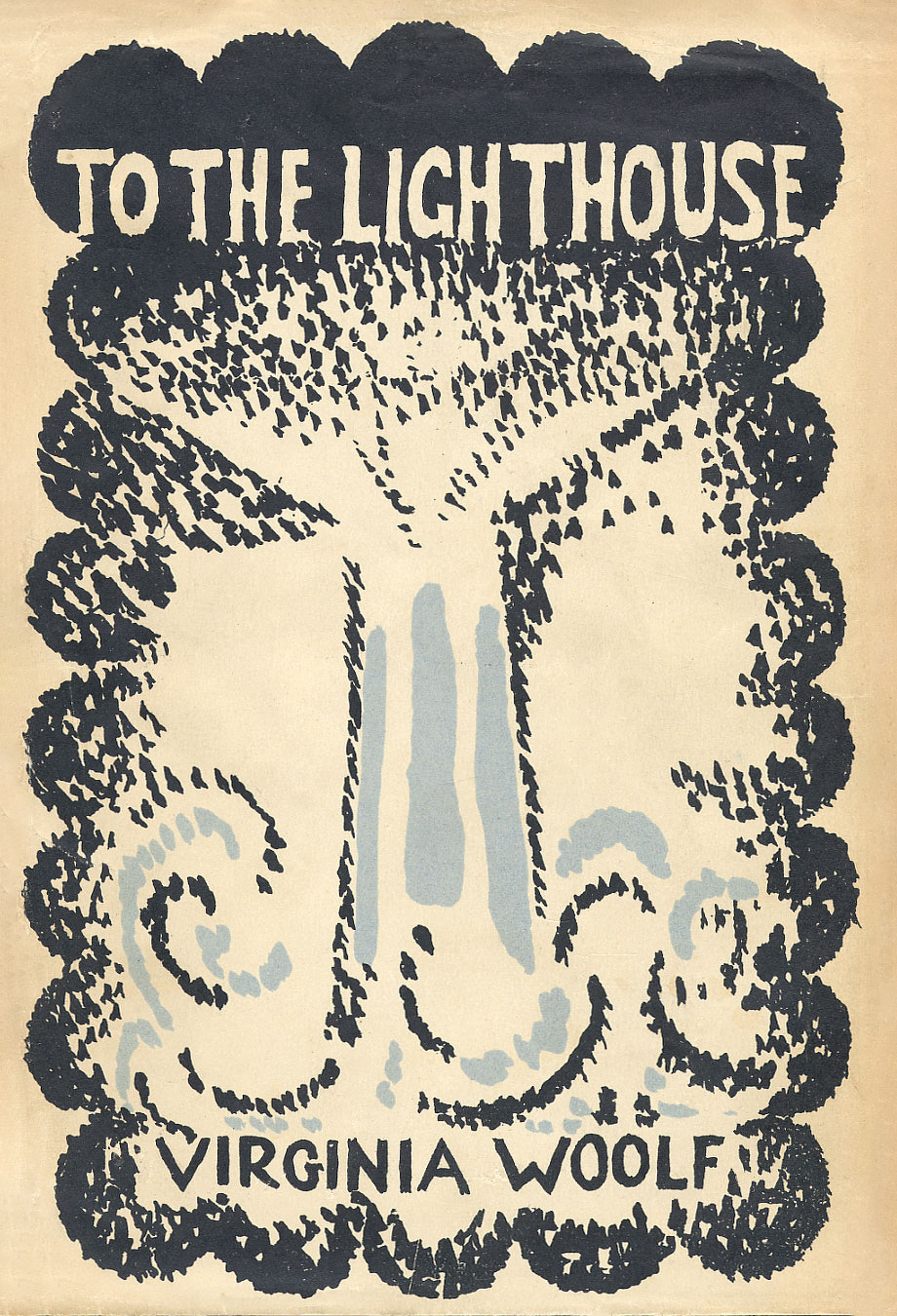

Cover of the first edition of To the Lighthouse (1927), designed and drawn by Woolf’s sister Vanessa Bell.

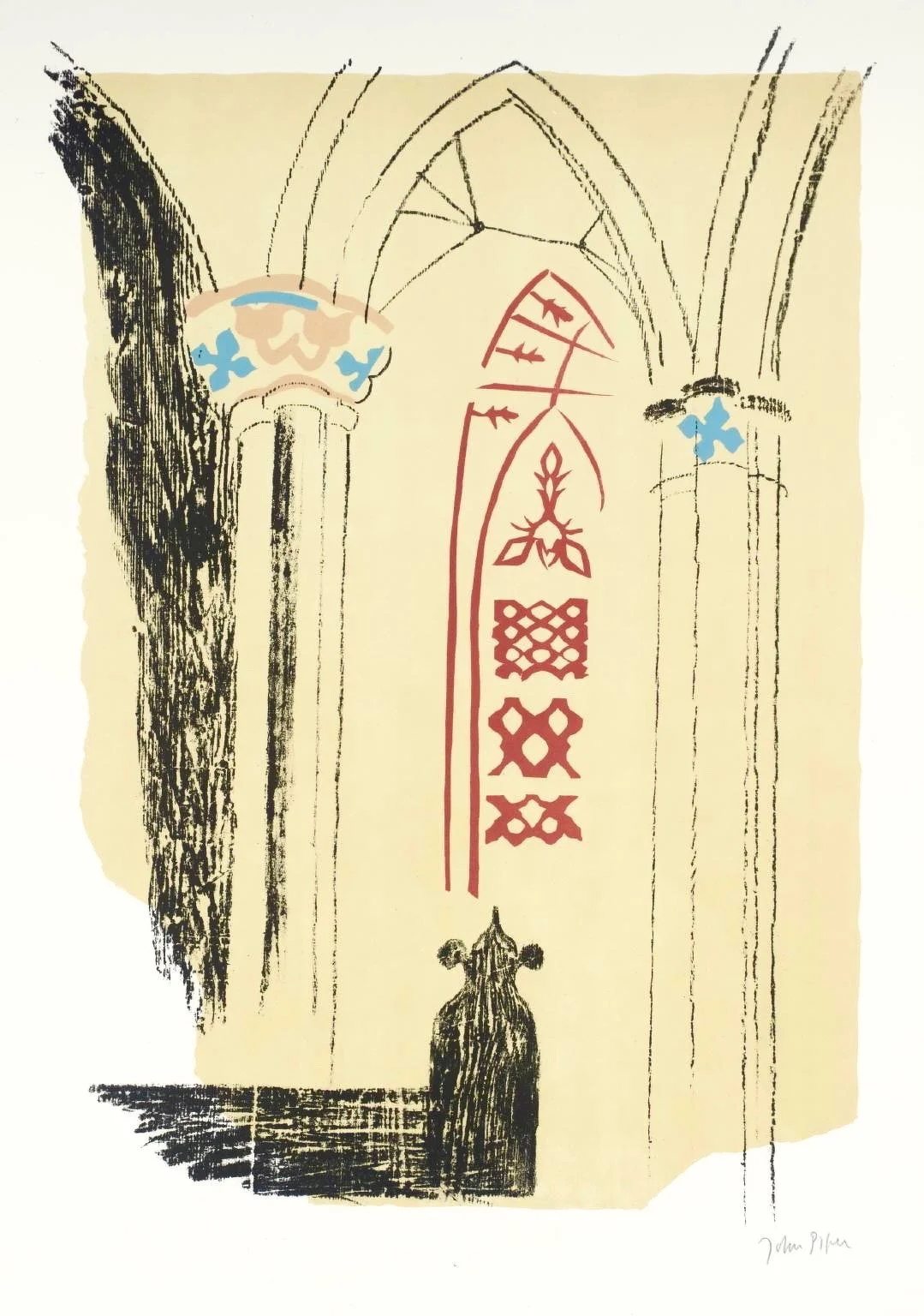

John Piper, Llan-y-Blodwell, Shropshire 1964

In art, I argue, process matters as much as product.

In his famous 2021 essay, “Moore’s Law for Everything,” [Sam] Altman made the following grandiose prediction:

“My work at OpenAI reminds me every day about the magnitude of the socioeconomic change that is coming sooner than most people believe. Software that can think and learn will do more and more of the work that people now do. Even more power will shift from labor to capital. If public policy doesn’t adapt accordingly, most people will end up worse off than they are today.”

Four years later, he’s betting his company on its ability to sell ads against AI slop and computer-generated pornography.

Finished reading: Yeah! Yeah! Yeah! by Bob Stanley. The first half is brilliant; then, starting around 1970, the pace picks up and Stanley’s attention starts to grow variable. There’s a bit of a British tilt: though he knows that country, and later alt-country, are important, he doesn’t have much to say about them — Gram Parsons, one of the most lastingly influential musicians of the last half-century, goes wholly unmentioned. Also, he is quite dismissive of Joni Mitchell; and inexplicably, given his British vantage-point, he has next-to-nothing to say about Led Zeppelin. Reading this book, you’d think that Marc Bolan was far more important than Zep. All that said, I learned a great deal from the first half of the book, and hope soon to make a playlist of cool & unusual songs Stanley mentions. 📚

I don’t know what makes a good social media network, but I do know what makes it so that when they go bad, you’re not stuck there. You and I might want totally different things out of our social media experience, but I think that you should 100 percent have the right to go somewhere else without losing anything. The easier it is for you to go without losing something, the better it is for all of us.

This is why I’m on the open web.

Two questions:

-

Do I want to read/watch/listen to this?

-

Should I read/watch/listen to this?

When I was younger the second question often dominated my decision-making. Now that I am officially ancient that question has virtually disappeared and the first one is usually the only one I ask. That’s been the single most notable change in my personality in these my declining years.

Why does Scott Alexander devote 30,000 words to examining the Fatima Sun Miracle? Because “if the God of Fatima exists, we are in deep trouble.”