Brewster Kahle, Internet Archive:

The dream of the Internet was to democratize access to knowledge, but if the big publishers have their way, excessive corporate control will be the nightmare of the Internet. That is what is at stake. Will libraries even own and preserve collections that are digital? Will libraries serve our patrons with books as we have done for millennia? A positive ruling that affirms every library’s right to lend the books they own, would build a better Internet and a better society.

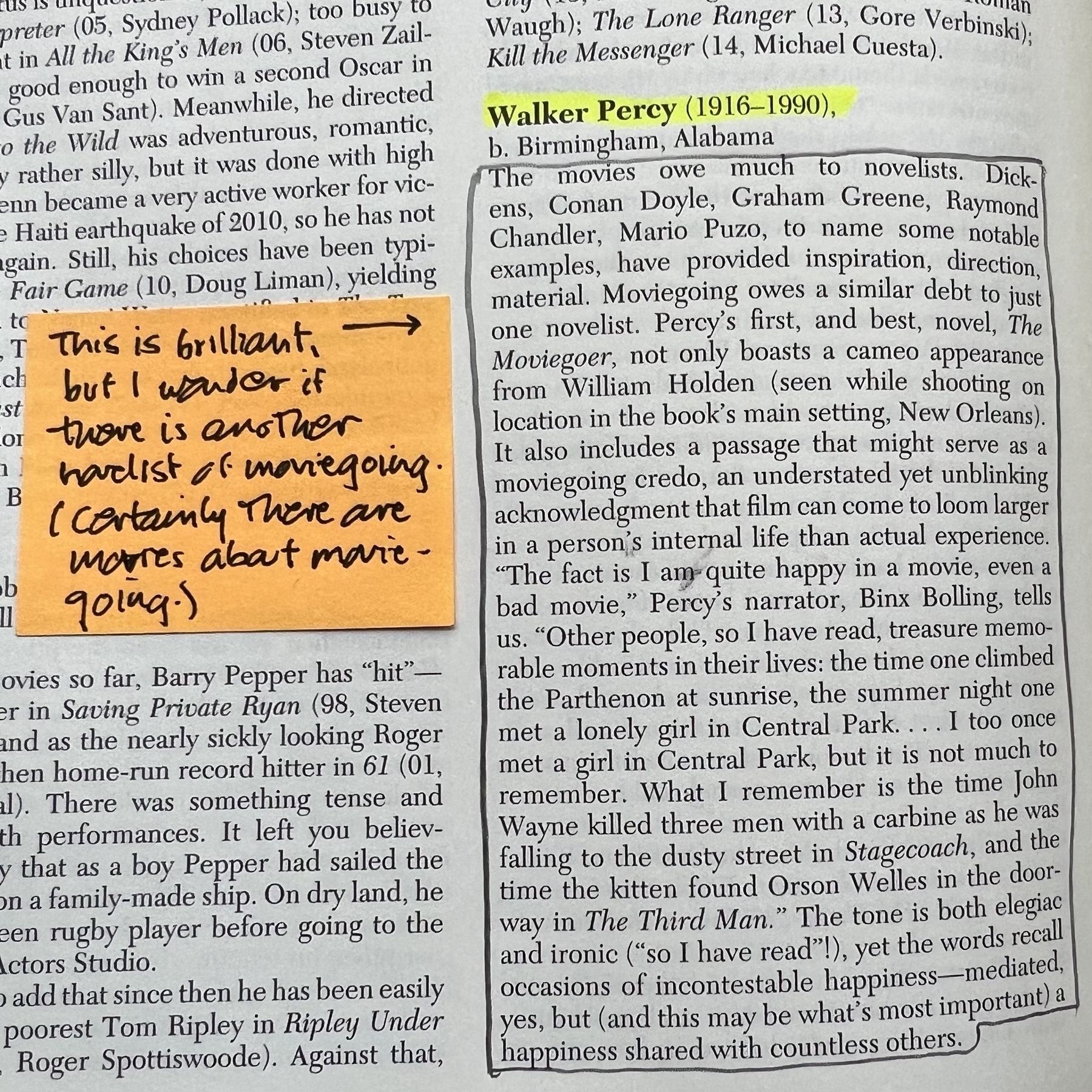

Finished reading: The New Biographical Dictionary of Film: Sixth Edition by David Thomson. This too I did not read every word of – it’s considerably longer than War and Peace – but it is an invaluable resource and you can find something delightful on almost every page. Thomson has the great gift of often being fascinatingly wrong. 📚

Finished reading: Paul and the Faithfulness of God by N.T. Wright. Didn’t read it all, but read most of it – all that I need. (Most of the rest involves disputes among New Testament critics that this amateur does not need to know about.) 📚

Angus has figured out how to get up onto our bed. Returning from the toilet this morning this is what I found in my place.

slight return

I’m back! — well, partially. Posting will be light for a while. But I certainly learned that for me micro.blog works best as a place to post images and sounds (and to make note of books I’m reading).

Oh, and you can’t trust Amazon with your newspapers and magazines either. If you want to own your reading and listening and viewing material, you just gotta buy your own copies.

The new issue of The Hedgehog Review is just extraordinary. I am especially taken by Malloy Owen’s essay on the strange history of critical theory. My annotated copy is available as a PDF here.

Lionel Shriver: “I don’t always want my novels to be focused on the culture wars, but I have used the culture wars and more broadly, I have found the whole experience of the last several years informative, not necessarily in a cheerful manner. It’s been very discouraging — in the same way that I found the whole Covid era incredibly discouraging — and I think less of humanity as a result.” Relatable.

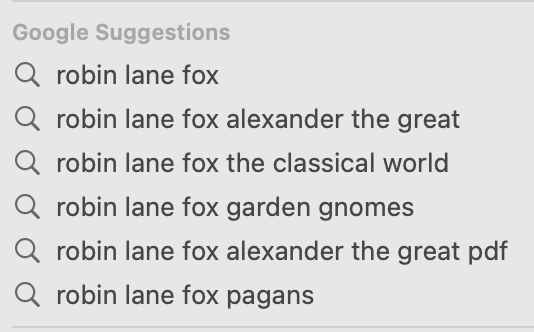

One of these things is not like the others

James Bridle: “The lesson of the current wave of ‘artificial’ ‘intelligence’, I feel, is that intelligence is a poor thing when it is imagined by corporations. If your view of the world is one in which profit maximisation is the king of virtues, and all things shall be held to the standard of shareholder value, then of course your artistic, imaginative, aesthetic and emotional expressions will be woefully impoverished.”

“A group of property developers have been ordered to rebuild a Grade II-listed pub that they demolished without permission. The historic Punch Bowl Inn at Hurst Green, Lancashire, needs to be rebuilt brick by brick within a year, a judge has ruled.”

Mark Zuckerberg famously said that the Twitter founders drove a clown car into a gold mine. Now it looks like he’s driving a Lamborghini into a garbage dump.

David Stromberg on Israel: “It is really an age-old question: When things turn dark in your country, do you resist from within or go into exile?”

Here I am on David Hume’s Guide to Social Media.

Here’s another one of my little experiments in sharing ideas: Paul Kingsworth recently published an essay and I annotated it.