Here I am on David Hume’s Guide to Social Media.

Here’s another one of my little experiments in sharing ideas: Paul Kingsworth recently published an essay and I annotated it.

I think if I could use only one recording to demonstrate how good vinyl can be, it would be this one. Spacious, rich, perfectly balanced.

Currently reading: Reporting World War II: Library of America 📚

“A Humanism of the Abyss” — my essay on the 50th anniversary of the publication of Oliver Sacks’ Awakenings — is unpaywalled.

Robin Sloan wants me to ask “What do I want from the internet, anyway?” I’ve been thinking about that a lot and I’ve decided that I want it to be (a) distributed, (b) slow, and (c) reticent. (Which may not answer his question.)

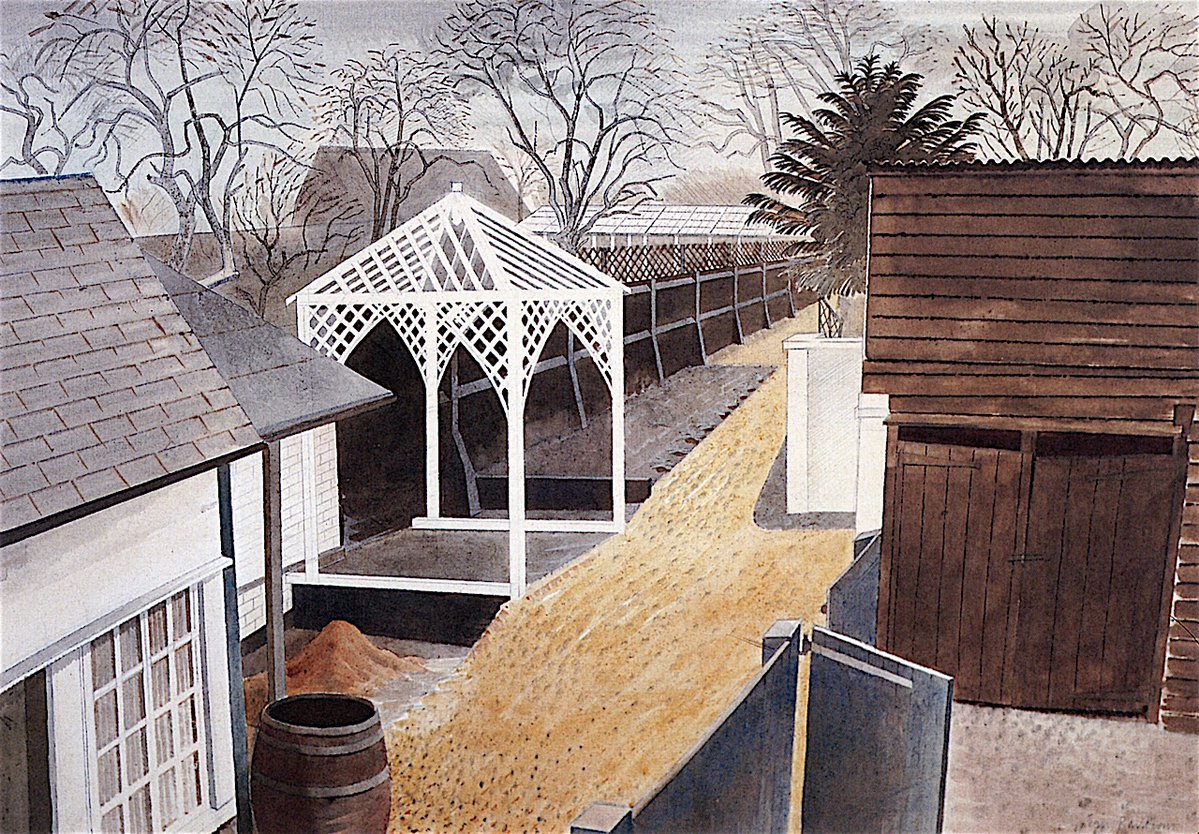

Garden Path by Eric Ravilious (1934)

Finished reading: The Lord of the Rings: 50th Anniversary, One Vol. Edition by J.R.R. Tolkien. I’m wondering how many times I’ve read this book straight through – maybe twelve? Fifteen? Every reading is different. This time I was especially moved by Eowyn’s story. 📚

That ridiculous black tail

Our friend David Hooker is an amazing artist, and we’re so excited about this fabulous new pot we got from him.

Huge if true

Over at my Buy Me a Coffee page, I explain the new ways I’ll be using micro.blog.

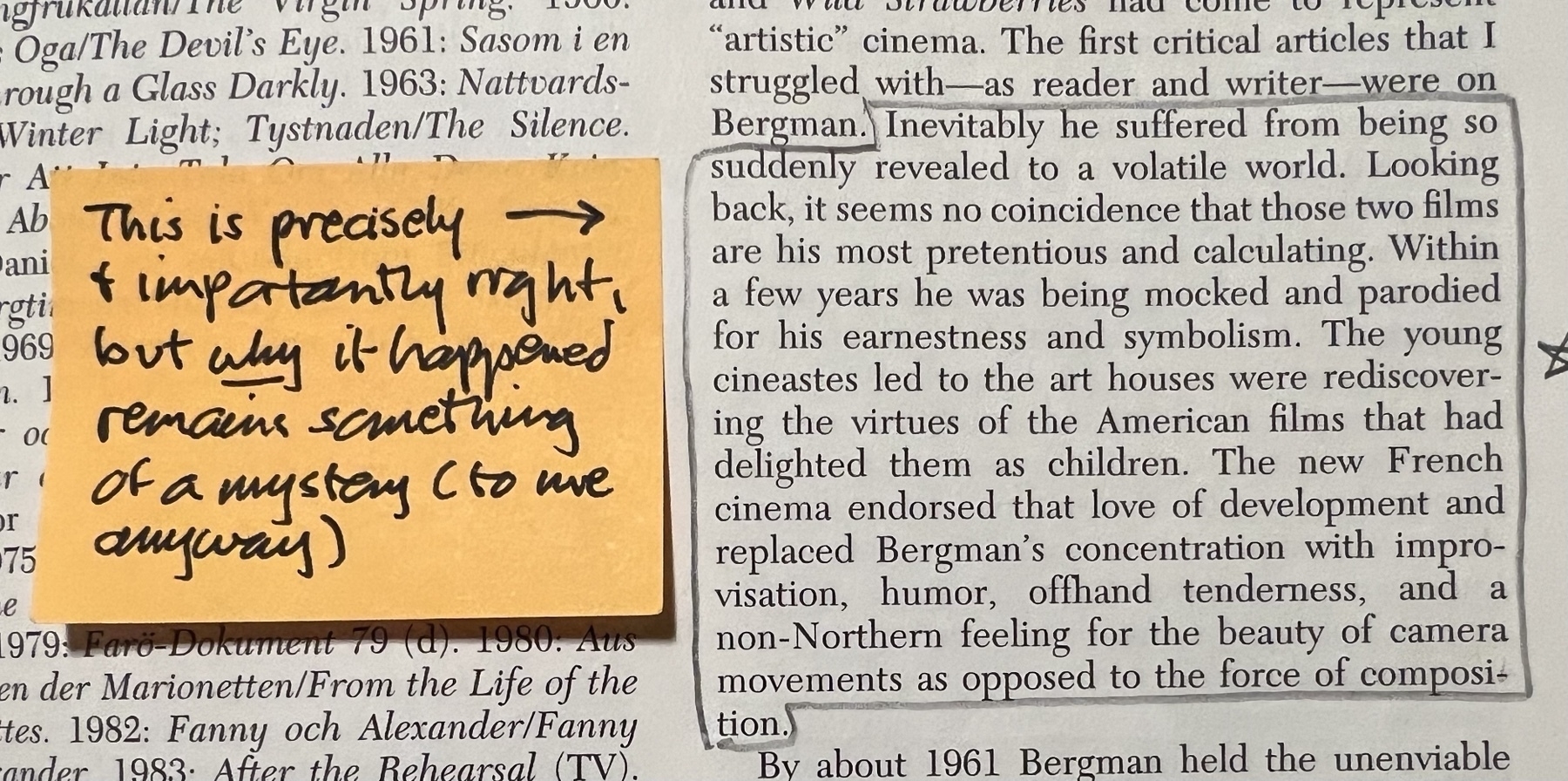

David Thomson on Ingmar Bergman

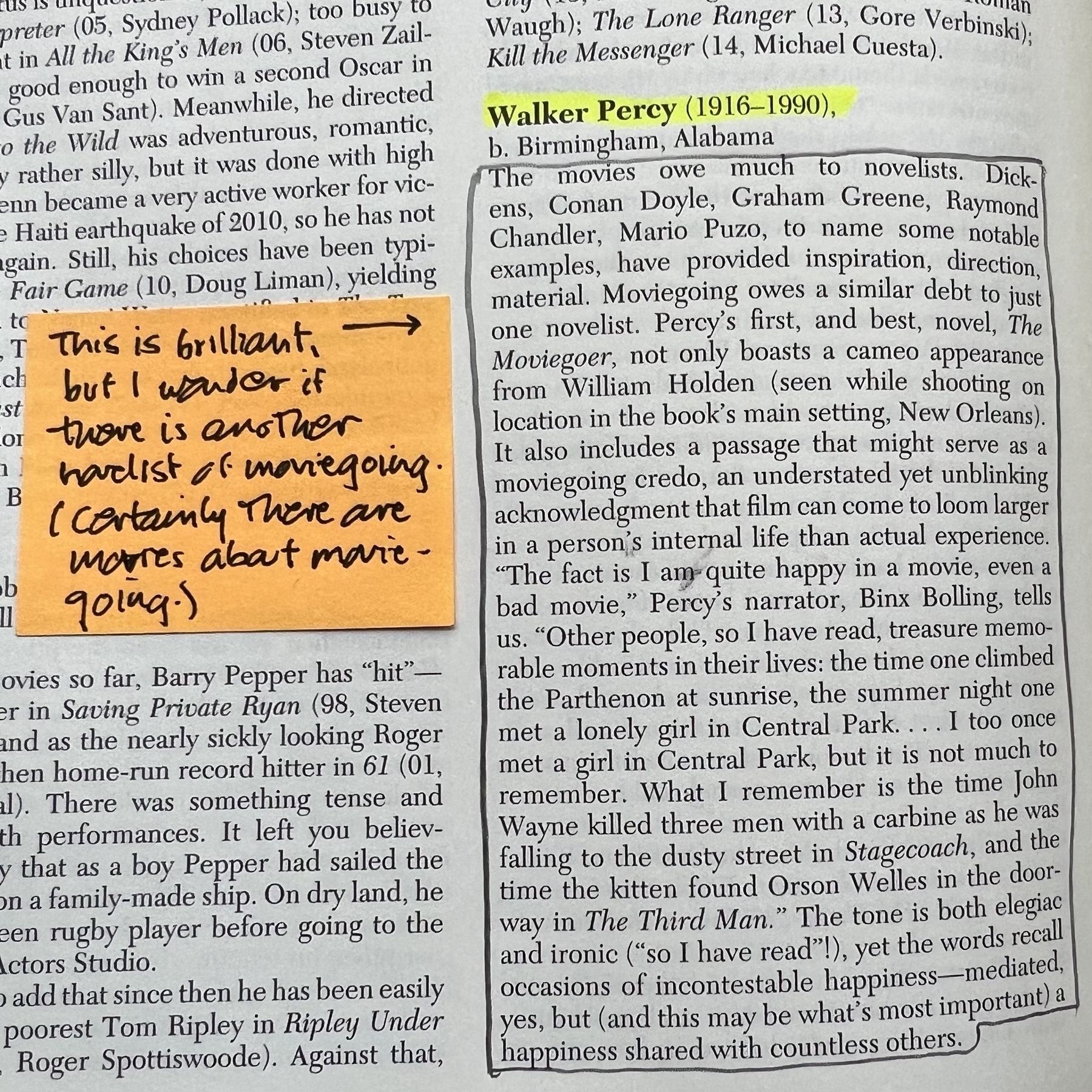

Currently reading: The New Biographical Dictionary of Film: Sixth Edition by David Thomson. This is another one of those that I won’t be finishing any time soon – and won’t ever “finish” in any strict sense. 📚

Cal Newport: “The open office boom is right up there with the spread of Slack as representing the peak of early 21st century distraction culture — a period in which the knowledge sector completely disregarded any realities about how human brains actually go about the difficult task of creating value through cogitation.”

Finished reading: Analogia: The Emergence of Technology Beyond Programmable Control by George Dyson. A fascinating, frustrating, and in the end I think incoherent book. 📚