Another pro tip: While you’re waiting a week for the limoncello to brew, add the juice from the Meyer lemons to bourbon and honey syrup to make Gold Rushes.

Pro tip: when life hands you Meyer lemons, make limoncello.

the end of the timeline era

With Mastodon, you’re not dealing with a giant, faceless company — or a constantly in-your-face CEO — making arbitrary decisions that are often impossible to understand or appeal. Instead, you join a Mastodon server — called an

instance

— run by an individual, company, or organization.

An individual, company, or organization equally free to make arbitrary decisions that are often impossible to understand or appeal. In a related article Fleishman writes,

Each Fediverse instance is its own Little Prince world that can choose to engage with other servers through federation, the interchange of information stored locally with other servers remotely. There’s no one in charge and no single place to go for definitive truth about the network.

“There’s no one in charge” on Mastodon-as-such, because Mastodon-as-such is just some open-source software, but there is very definitely someone in charge on any instance you join, and whoever that is can ban you any time for any reason or none. You can only escape that by creating your own instance of Mastodon, which possibly 0.01% of its users have the chops and resources to do.

Mastodon has certain virtues, at least for some, but let’s not attribute to it powers it does not have. In almost every respect Mastodon functions precisely as Twitter did, with, as I have said before, every single one of Twitter’s perverse incentives. And if you’re not running your own instance you’re not one whit less vulnerable than you were in Elon World.

People who are tempted by Mastodon should at least consider this from Luke: “I’m on Mastodon, but I’m bored of what I call ‘the timeline era.’ Scanning an unending stream of disconnected posts for topics of interest is no longer fun, I prefer deciding what to read based on titles, or topic-based discussion.” There are more things on the internet, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your timeline. And off the internet: far, far more.

note to self

Repair begins with redirection. Commencing the repair of our cultural ecosphere by shifting attention to neglected things.

Focal practices ➡ hypomene ➡ the good work of repair.

Or: shun the smooth things, get back to the rough ground. But rough ground must be thoroughly prepared for the seeds you want to sow. Only then can roots grow deep. We want food; we’re hungry; our temptation is to scatter the seed blindly and hope for the best. But that’s a recipe for failure.

What are the focal practices of the wise sower, the responsible gardener?

Wendell Berry, from “Standing by Words”:

As industrial technology advances and enlarges, and in the process assumes greater social, economic, and political force, it carries people away from where they belong by history, culture, deeds, association, and affection. And it destroys the landmarks by which they might return. Often it destroys the nature or the character of the places they have left. The very possibility of a practical connection between thought, and the world is thus destroyed. Culture is driven into the mind, where it cannot be preserved.

Dunsany's games

In the class I’m currently teaching on fantasy, we are moving from George MacDonald’s Phantastes to Lord Dunsany’s The King of Elfland’s Daughter. Phantastes is a classic quest romance, with the added dimension, as Harold Bloom pointed out in a justly famous early essay, that in Romantic and post-Romantic narrative any quest will be primarily an internal one, a psychological or spiritual searching.

More critics than I can readily count have said that Dunsany is the father of modern fantasy, but it’s very interesting in light of that claim to see how frequently he subverts the expectations of fantasy in all of its forms. For instance … well, why don’t you take just a few minutes now and read a very short story of his called “The Hoard of the Gibbelins”? I’ll wait.

See what he did there? One of the things that we always hear in quest romances, and in other forms of fantasy, is that the protagonist of our story is striving to succeed in an endeavor which many before him have unsuccessfully attempted. Our interest, then, in this protagonist is closely related to our belief that he will indeed succeed in his quest. But the protagonist of “The Hoard of the Gibbelins” does not succeed. It’s very shrewdly and wittily done.

Interestingly enough, the protagonist of that story has almost exactly the same name (Alderic) as the protagonist of The King of Elfland’s Daughter (Alveric). And that might suggest to us that Dunsany wants to play with the conventions and expectations of his chosen genre in that novel as well. Let’s take a look.

In the first chapter, the prince Alveric is given a task, a great Quest to pursue, and … he completes the quest by the end of chapter 3. The story has barely started, and it seems to be over. What that tells us is that Dunsany isn’t actually interested in Quest, at least not in any conventional way, and perhaps, at this point, we should remember that the name of this novel is not The Quest of Prince Alveric but rather The King of Elfland’s Daughter and revise our expectations in light of that title.

Some of you will know that long ago a scholar named A. J. Greimas – the OG Ayjay, as it were – declared that all stories are comprised of what he called actants. There were six of these, in three pairs: subject/object, sender/receiver, helper/opponent. In a standard quest romance, the Quester, however odd or ambiguous his quest, is always the subject. Thus our interest in Phantastes is always what happens to Anodos; we see the world through his eyes.

But in Dunsany’s novel things are different. One could say that in the first three chapters of the story, Alveric is the subject, the persons and things of Elfland as the objects, and various figures are helpers or opponents. The primary opponent seems to be the King of Elfland, the primary helper the witch Ziroonderel. But after the completion of his quest, Alveric recedes from the novel for quite some time and the focus moves elsewhere, primarily to the denizens of Elfland. At this point, we would do better to think of the subject of the story as Lirazel and the objects of the story as the things of our world – what Dunsany typically calls “the fields we know” –; and then we might see her husband, her son, and her father as helpers or opponents of hers. In MacDonald’s work women are almost always the helpers or opponents of men; but Lirazel is much more than that even if we can’t quite see her as in any simple sense the protagonist of the story.

It’s a very curious novel with shifting perspectives, and continual reminders that the understanding of one world is never to be given priority over the understanding of another, nor is the understanding of one character to be definitive for the readers. It’s full of sly subversions of the tropes of fantasy, often presented en passant. For instance, there’s a delightful little moment when a troll from Elfland comes to our world on his own Quest, happens to encounter a child, and suggests that perhaps the child would want to go to Elfland — from which, as we know from our fairy tales, she would never return. The child mulls the offer for a moment and then declines, because her mother has made her a jam roll and she wants to eat it. So nothing happens. The troll goes on about his business.

But we haven’t yet talked about senders and receivers. Here too Dunsany complicates things. At the outset the King of Erl sends his son Alveric to Elfland, and Elfland quite reluctantly receives him. But from that point on we are treated to a series of sendings and receivings, characters moving back and forth between Elfland and the fields we know, Elfland itself contracting and expanding — but hovering over it all are the three great runes of the King of Elfland: the magic he can send forth in power that no one can contest or deflect. The whole story builds to a final sending, a conclusive receiving.

It is a very strange book — it gets stranger the more you think about it — and is, I believe, a genuine masterpiece.

focal practices for pilgrim people: intervals

In one sense the question I posed in an earlier post — What are the proper focal practices for a pilgrim people? — has an obvious answer. In a sermon John Wesley wrote that the “chief … means” of God’s grace to us

are prayer, whether in secret or with the great congregation; searching the Scriptures (which implies reading, hearing, and meditating thereon); and receiving the Lord’s Supper, eating bread and drinking wine in remembrance of Him: And these we believe to be ordained of God, as the ordinary channels of conveying his grace to the souls of men.

Surely it is true, and has been true as long as Christians have walked the earth, and will always be true, that these three practices are permanently and non-negotiably focal for Christians. If we’re not doing these, then we’re going to be distracted, diffracted, “blown about by every wind of doctrine.”

But if these are the “ordinary channels” by which God conveys grace to us, might there be, in certain times and places, extraordinary channels — channels especially appropriate to a given context? I think so, and in this and future posts will be drawing on Byung-Chul Han’s The Burnout Society to identify some.

In this post I want to talk about intervals. In an especially provocative passage — and in another, later post I’ll discuss its context — Han writes,

Only by the negative means of making-pause can the subject of action thoroughly measure the sphere of contingency (which is unavailable when one is simply active). Although delaying does not represent a positive deed, it proves necessary if action is not to sink to the level of laboring. Today we live in a world that is very poor in interruption; “betweens” and “between-times” are lacking. Acceleration is abolishing all intervals. In the aphorism, “Principal deficiency of active men,” Nietzsche writes: “Active men are generally wanting in the higher activity ... in this regard they are lazy.... The active roll as the stone rolls, in obedience to the stupidity of the laws of mechanics.” Different kinds of action and activity exist. Activity that follows an unthinking, mechanical course is poor in interruption. Machines cannot pause. Despite its enormous capacity for calculation, the computer is stupid insofar as it lacks the ability to delay.

Almost everyone at times has the sense that we are not using our technologies but are being used by them. Which is why, in the long run, as Jaron Lanier has pointed out, “the Turing test cuts both ways. You can’t tell if a machine has gotten smarter or if you’ve just lowered your own standards of intelligence to such a degree that the machine seems smart. If you can have a conversation with a simulated person presented by an AI program, can you tell how far you’ve let your sense of personhood degrade in order to make the illusion work for you?” We therefore come to imitate the distinctive stupidity of machines. If we are to be stupid, at least let our stupidity be human.

So maybe the first focal practice, the one that enables all the others, is simply this: to pause. To create intervals in our busyness. Maybe we will later fill those intervals with prayer, for instance, but just to create them is the first desideratum. Pause, and breathe — that alone declares our humanity and distinguishes us from our machines. The pilgrim pauses along the Way, and in that manner combats the laziness peculiar to a technologically accelerated age.

Currently reading: Standing by Words by Wendell Berry 📚

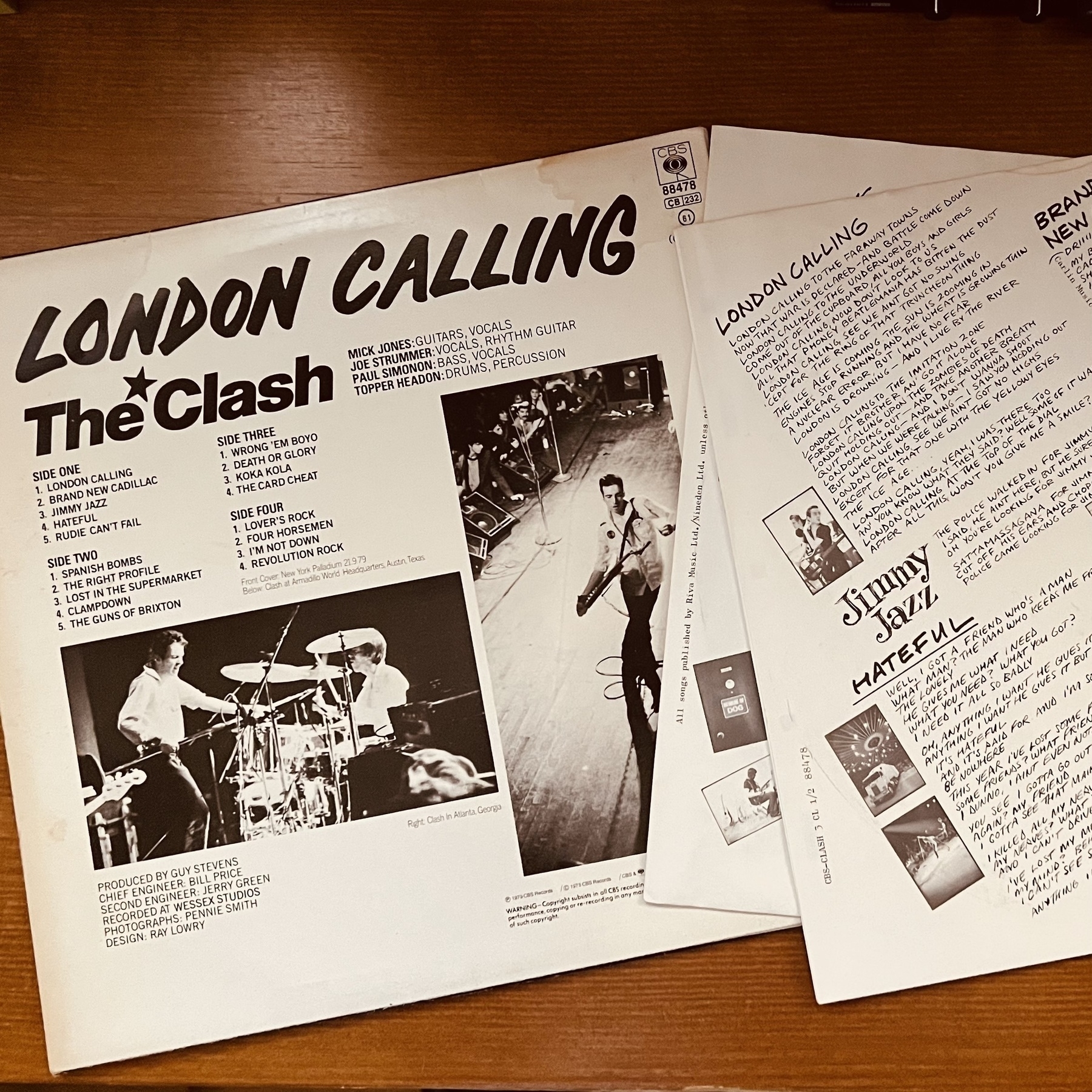

My buddy Rob Miner bought this for me in Amsterdam – and it sounds great. But I’m concerned that I’ll soon be haunting record stores and asking questions like “Do you happen to have the Dutch pressing? I’m led to believe that it’s especially fine.”

burn after reading

Dear colleagues,

I must congratulate you all on what is, so far, a perfect execution of our Plan. You will recall that when we first met, more than a decade ago, we found ourselves confronted with a dramatic decline in enrollment in university humanities courses — throughout the Western world, but especially in the U.S.A. The self-declared radicals who dominated teaching in the humanistic disciplines seemed determined to alienate students as thoroughly as possible from literature, philosophy, and the arts; meanwhile, parents were frantically pushing their offspring towards courses in business and computer science. Very few young readers and thinkers could resist this double discouragement, especially since the forces doing the discouraging seemed in other respects to stand for opposing visions of what the world should be.

We quickly came to agreement on two points: first, that our chances of restoring the university humanities to their proper calling were so small that we could scarcely justify extending any efforts in that direction; and second, that in any case what matters in the long term is not the university disciplines but rather the cultural achievements that those disciplines once cared for: the novels and plays and poems, the treatises and dialogues, the sonatas and symphonies, the paintings and sculptures and beautifully designed buildings.

The key moment in our deliberations, as I recall, came when one of you reminded us of a (probably apocryphal) statement by the novelist Stendhal, who upon eating ice cream for the first time declared, “This is perfectly delicious. What a pity it isn’t forbidden.”

What a pity it isn’t forbidden. With that thought our Plan was born. The key, we realized, was to transform the works we love from objects of praise to objects of suspicion: things that required “trigger warnings” and deserved skeptical critique — perhaps utter denunciation for racism or homophobia or racism or ableism or … anything else we could think of.

Of course, we had to be careful — we had to work by suggestion and implication. We thought that if we made these accusations directly and explicitly we would be laughed at. Looking back, we can see that our caution was in one sense unnecessary: in this environment, no charge against great works of art could possibly be too outrageous. Still, our caution has served us well: We whispered the quiet part, and our colleagues eagerly said the quiet part out loud. Soon enough they were pronouncing their fatwas day in and day out.

What a pity it isn’t forbidden — the universal human desire for what we are told to hate and despise is our greatest ally. If we persist in our efforts, perhaps one day even Bach will be wholly excluded from concerts, even Shakespeare from theaters, even Homer and Dante from literature classes … and then the Renewal can at last begin.

Yours in the Great Cause,

Comrade Gamma

Re: yesterday’s cover art, How to Think has now been translated into:

- Arabic

- Chinese (PRC)

- Chinese (Taiwan)

- Dutch

- Korean

- Portuguese

- Spanish

- Turkish

- Vietnamese

reflections

Phantastes is all about doubling: reflections in mirrors, a cave of making juxtaposed to a grotto of destruction, a loving womanly beech-tree versus a malicious Maiden of the Ash, a bedroom in an ordinary Victorian home and the twin of that bedroom in Fairy Castle. All of these doublings are most fully embodied in the contrast between our world — where the waters reflect but the sky does not — and Fairy Land — where just the opposite is true.

On the day after his 21st birthday, a man named Anodos enters Fairy Land, undergoes many adventures and trials, and returns to his home twenty-one days later — though the period feels to him like twenty-one years, that is, the equivalent of the time he had previously spent in our world. (The one life mirrors the other.) His parents both being dead, he has now, at reaching his majority, become the head of his household:

My mind soon grew calm; and I began the duties of my new position, somewhat instructed, I hoped, by the adventures that had befallen me in Fairy Land. Could I translate the experience of my travels there, into common life? This was the question. Or must I live it all over again, and learn it all over again, in the other forms that belong to the world of men, whose experience yet runs parallel to that of Fairy Land? These questions I cannot answer yet. But I fear.These concerns about the effects of such doubling (such “parallel” experiences) are, it seems clear, George MacDonald’s own concerns about the writing of fantasy. In his essay “The Fantastic Imagination” MacDonald confesses quite directly a complication in the writing of what we would now call fantasy but when he called (as he himself said, for lack of a better term) fairy tale:

- On the one hand, among the literary genres the fairy tale has a unique power to “wake a meaning” in its readers — and this is a great thing. “The best thing you can do for your fellow, next to rousing his conscience, is — not to give him things to think about, but to wake things up that are in him; or say, to make him think things for himself.” In seeking this effect the writer of a fairy tale is imitating Nature: “The best Nature does for us is to work in us such moods in which thoughts of high import arise.”

- On the other hand, there is nothing the writer of the fairy tale could or should do to determine what meaning is awakened in its readers. He says this repeatedly. "A genuine work of art must mean many things; the truer its art, the more things it will mean.” To determine that a single meaning be extracted from the tale is to write an allegory, and “a fairytale is not an allegory. There may be allegory in it, but it not an allegory. He must be an artist indeed who can, in any mode, produce a strict allegory that is not a weariness to the spirit.” No, “the greatest forces lie in the region of the uncomprehended,” and therefore the fairy-tale writer must be willing to accept, and indeed must (by opening his mind and spirit) court the uncomprehended. Otherwise, why bother writing a fairy tale?

If a writer's aim be logical conviction, he must spare no logical pains, not merely to be understood, but to escape being misunderstood; where his object is to move by suggestion, to cause to imagine, then let him assail the soul of his reader as the wind assails an aeolian harp. If there be music in my reader, I would gladly wake it. Let fairytale of mine go for a firefly that now flashes, now is dark, but may flash again. Caught in a hand which does not love its kind, it will turn to an insignificant ugly thing, that can neither flash nor fly.A work of fantasy, then — in addition to being a firefly, and a wind —, may be described as a mirror, but as with the Mirror of Galadriel, what one sees in it is largely determined by who one is. (And anyway, if G. C. Lichtenberg was right, that’s true of all books without exception: “A book is like a mirror,” he said; “If a jackass looks in, you can’t expect an apostle to look out.”)

But if this mirror will provide any kind of reflection at all in what Lord Dunsany liked to call “the fields we know,” what’s necessary, MacDonald believes, is a kind of consistency in the imagined world one offers to the reader.

Man may, if he pleases, invent a little world of his own, with its own laws; for there is that in him which delights in calling up new forms — which is the nearest, perhaps, he can come to creation. […] His world once invented, the highest law that comes next into play is, that there shall be harmony between the laws by which the new world has begun to exist; and in the process of his creation, the inventor must hold by those laws. The moment he forgets one of them, he makes the story, by its own postulates, incredible. To be able to live a moment in an imagined world, we must see the laws of its existence obeyed. Those broken, we fall out of it.This is obviously an adumbration of Tolkien’s more famous concept of “secondary worlds” — but it is clear (see my previous post on mythopoeic promiscuity) that when MacDonald talks about the “laws” of an imagined world he cannot possibly mean the kind of consistency in world-building that Tolkien so prized, and so lamented the absence of in Lewis’s fiction.

I think the laws that MacDonald refers to are mystical and spiritual, and unconnected altogether to the material furniture of the fictional environment. But I need to think about that further — and about the specific ways that MacDonald’s crazy-quilt fictional world just might possess a consistency that allows it to serve as a useful mirror of our own.

R. I. P. Lin Brehmer

I’m a Texas guy now and proud of it, but Chicago is deep in my heart and always will be — and an essential part of my Chicagoland experience for three decades was WXRT, one of the handful of truly great American radio stations. What made WXRT so wonderful could be summed up by pointing to Lin Brehmer, who came to Chicago a couple of months after I arrived in the area and who hand-crafted amazing musical sequences, year after year after year, until shortly before his death yesterday. (XRT was one of the last big stations to trust its DJs to program their own music — I don’t know whether they still do.)

For much of his time at XRT Lin featured little audio essays under the general title “Lin’s Bin,” and they were reliably entertaining. I particularly remember two of them.

One came soon after the death of Stevie Ray Vaughan in 1990, when Lin was tasked with trying to get comments on SRV from various musicians. He described his comical attempts to get in touch with Keith Richards, attempts that ended when he was hung up on by the assistant to Keef’s assistant. Discouraged, he turned to the next person on his list: the great blues singer Koko Taylor. He dialed the number he had, and a male voice answered:

Voice: “Hello?”

Lin: “Um, yeah, I’m trying to get in touch with Koko Taylor.”

Voice: “Hang on [hand over receiver to muffle voice] … HEY MOM!!!”

The second story involved Lin’s remembrance of growing up in New York City and getting his first opportunity, as a teenager, to go to a show at the now-legendary Fillmore East. Did he decide to see Jimi Hendrix? Led Zeppelin? The Allman Brothers? Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young? No, Lin didn’t choose any of those. He decided, he said, to see … and here he paused, only to resume with sonorous sobriety: Grand Funk Railroad.

Lin, you were one of the greats. R.I.P.

UPDATE: A really nice Twitter-thread tribute to Lin by the legendary producer Steve Albini.

There’s a lot of this. Also, Angus is committed to (a) peeing outside and (b) pooping inside.

Cover for the forthcoming Arabic translation of How to Think.

Currently reading: The King of Elfland’s Daughter by Lord Dunsany 📚

enshittification

The ‘Enshittification’ of TikTok | Cory Doctorow:

Here is how platforms die: First, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.

I call this enshittification, and it is a seemingly inevitable consequence arising from the combination of the ease of changing how a platform allocates value, combined with the nature of a "two-sided market," where a platform sits between buyers and sellers, hold each hostage to the other, raking off an ever-larger share of the value that passes between them.

A scathing and utterly compelling treatise, dedicated chiefly to pointing out the comprehensively obvious fact — which hundreds of millions of people seem determined not to face — that TikTok obeys the same enshittifying logic as every other social media platform: “TikTok … is just another paperclip-maximizing artificial colony organism that treats human beings as inconvenient gut flora. TikTok is only going to funnel free attention to the people it wants to entrap until they are entrapped, then it will withdraw that attention and begin to monetize it.” Ergo: “It's too late to save TikTok. Now that it has been infected by enshittifcation, the only thing left is to kill it with fire.” Q.E.D.

the buffered self in Fairy Land

A number of years ago I wrote an essay called “Fantasy and the Buffered Self” in which I applied Charles Taylor’s distinction between “porous” and “buffered selves” to the question of why fantasy is such a popular genre in our putatively disenchanted age. There’s a wonderful illustration of this distinction in Chapter VIII of George MacDonald’s Phantastes. Wandering in the woods of what he believes to be Fairy Land, our protagonist Anodos comes across a farmhouse into which he is welcomed by a kindly woman. Anodos tells her about his frightening experiences in the mysterious forest, and she replies,

“It is just as I feared, … but you are now for the night beyond the reach of any of these dreadful creatures. It is no wonder they could delude a child like you. But I must beg you, when my husband comes in, not to say a word about these things; for he thinks me even half crazy for believing anything of the sort. But I must believe my senses, as he cannot believe beyond his, which give him no intimations of this kind. I think he could spend the whole of Midsummer-eve in the wood and come back with the report that he saw nothing worse than himself. Indeed, good man, he would hardly find anything better than himself, if he had seven more senses given him.”Anodos meets this (as it were) well-buffered farmer, who is openly skeptical of any hint that there are strange creatures in the forest — "It is only trees and trees, till one is sick of them” — and then is put to bed in a room that looks not into the forest but across a plain open field.

I was somewhat sorry not to gather any experience that I might have, of the inhabitants of Fairy Land; but the effect of the farmer’s company, and of my own later adventures, was such, that I chose rather an undisturbed night in my more human quarters; which, with their clean white curtains and white linen, were very inviting to my weariness.Exhausted by his own porosity, Anodos seeks some protective buffers, some “more human quarters,” to shield him from his “own later [i.e. recent] adventures.” Seek and you shall find — even deep in the heart of Fairy Land.In the morning I awoke refreshed, after a profound and dreamless sleep. The sun was high, when I looked out of the window, shining over a wide, undulating, cultivated country. Various garden-vegetables were growing beneath my window. Everything was radiant with clear sunlight. The dew-drops were sparkling their busiest; the cows in a near-by field were eating as if they had not been at it all day yesterday; the maids were singing at their work as they passed to and fro between the out-houses: I did not believe in Fairy Land.