master to master

One of Christian’s Gibsons has survived, and here it is being played by the (also great) Julian Lage:

The English language is beautiful. It’s immensely rich and untidy with so many influences from other cultures, and I glory in it. People say to me that they have to go to the dictionary. Is that a great trouble? The dictionary is one of the most precious things you have in your house. You should be thanking me for the excuse to go to it. I say to them: “I bet when you went to look up whatever word, you came across four or five new ones. So you gained! I did you a favour!”

Alas, most of Banville’s readers would’ve looked up the words on Google. It’s only the dictionary in codex form that works the way Banville wants it to work — the way it should work. Trust me on that — and also trust my buddy Austin Kleon. If you don’t have any other books in codex form, have a dictionary and a Bible. They’ll surprise you and teach you every time you pick them up.

P.S. Unrelated, but here’a another great passage from that interview:

You know, someone said to me recently: “John, I suppose you’ll be writing your Covid novel?” I said: “I certainly will not, and I hope nobody else does either.” The art of fiction isn’t for commenting on events of the time. It may do that, but that’s not its object, which is to imagine the world.

Don’t know why that book info has the author’s name in Russian, but it looks cool so I decided to keep it.

Currently reading: The Complete Short Novels by Антон Павлович Чехов 📚

Musil was not the only writer of his time to think of the essay as the method and intellectual mode most appropriate to ethical reflection. A predilection for this flexible genre had taken strong root by the end of the nineteenth century, with brilliant standards established by Søren Kierkegaard, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Friedrich Nietzsche, and half a dozen prominent others. Their essays bent “positivistic” accounts of objective phenomena to the purposes of feeling and subjective need, to matters of spiritual and moral import. A loose manner of prose composition without fixed rules of method — incorporating aphorism, lyrical condensation, confession, invective, and satire — the essay straddled a spectrum along which Western metaphysics seemed to have arrayed two components of human experience: head and heart, science and art, truth and fiction, body and soul, law and desire.

This is why the essay is such a culturally vital and underrated genre, a topic on which I hope soon to write an … essay, I guess.

[Some of you may have seen that I originally posted this as a screenshot from Instapaper, which was easy and looked pretty good … but because it was an image rather than text (a) the text so imaged didn’t resize properly in different-sized browser windows and (b) the content isn’t searchable. So I’m back to the usual way of posting. But I dunno, I might try again at some point; it not being searchable isn’t such a big deal if I have tags. The value for me is that it’s a way of sharing with less friction.]

You Can Forget About Crypto Now: “Imagine your debit card suddenly stopped working because the executives at your bank were out making high-risk trades with your money while you were trying to pay for groceries — that’s roughly analogous to what Bankman-Fried is accused of pulling off.”

This Adam Neely video on the ways that intellectual property law is simply unsuited to music is just superb.

Currently reading: The Quest for Corvo: An Experiment in Biography by A.J.A. Symons 📚

Prediction: By this time in 2024, Elon will have sold Twitter to people who will pledge to return it to the Good Old Days of 2018. And all the journalists and politicos will rush back. Mark my words: Revenant Twitter is coming.

The most amazing part of this story is the teacher who says that he used to keep his smartphone on his desk so he could “check in with the outside world” while he was teaching.

negative worlds all the way down

Here's something people have been asking me to weigh in on for quite a while, but I’ve been putting it off, because ... well, what’s the point? But here at last I am.

You know that argument by Aaron Renn about “The Three Worlds of Evangelicalism"? Well, it's wrong. Let me explain ... no, there is too much. Let me sum up.

I can sum up just by quoting one of the first parts, because that is where the argument goes wildly off the rails:

Positive World (Pre-1994): Society at large retains a mostly positive view of Christianity. To be known as a good, churchgoing man remains part of being an upstanding citizen. Publicly being a Christian is a status-enhancer. Christian moral norms are the basic moral norms of society and violating them can bring negative consequences.

The “pre-1994” timeframe is obviously wrong. Few of the Founding Fathers held anything remotely approximating orthodox Christian faith; Abraham Lincoln had famously unknowable and shifting religious beliefs, and never joined a church. At the time of the Founding probably no more than 10% of Americans belonged to any church. You can get the details on all this in Mark Noll’s magisterial America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln; America became a markedly more religious country in the 1950s, a process described by George Marsden in another authoritative history, The Twilight of the American Enlightenment. Turns out that for much of America’s history, and in most of America’s places, whether someone was demonstrably a Christian or not really didn’t matter all that much. You can find that out, if you take the time.

So, you see, we’re already in the midst of major difficulties. Renn has begun with a big historical claim that is demonstrably untrue. If instead of “Pre-1994” he had written “1945-1994” then we could at least have proceeded. So let’s pretend he did and come to his first sentence.

That sentence is the general claim, the next three unpack it. Sentence 2 strikes me as being generally correct, but irrelevant or ambiguous in import. (Was Jesus considered “an upstanding citizen”?) Sentence 3 would be correct if the phrase “being a Christian” were replaced with “professing Christianity.” Sentence 4 would be correct if its first word were “Some,” but because it isn’t, the sentence is incorrect, and incorrect in a way that destroys the entire argument.

Here’s what I mean: Some Christian moral norms carried social authority in many though not all parts of America. For instance, generally speaking, a married person could not openly conduct extramarital affairs, nor could an unmarried one be openly promiscuous. Certainly homosexuality was almost always seen as a sin. Whether divorce damaged you socially — well, that varied a lot from place to place. Renn doesn’t cite any examples, so I don’t know what else he might have in mind. Maybe “honor your father and mother”? — That certainly was a commandment held in far higher regard before the social upheavals of the Sixties.

But for much of America’s history there were very large sections of the country in which, if you wanted to argue that all human beings are made in the image of God and the laws of America should in this respect follow the law of God, you were, shall we say, unlikely to get a respectful hearing. (And as David French recently pointed out, those problems, and other related ones, haven’t altogether gone away.) Does Renn seriously think that the slaves in the cotton fields singing their spirituals were living in a Christianity-positive world? But wait — that’s pre-1945, sorry. Does Renn think that six-year-old Ruby Bridges, praying for those who cursed and reviled her, was living in a Christianity-positive world? (And, to me anyway, this ain’t ancient history: Ruby Bridges is just four years older than I am.) Or Jonathan Daniels, who stood between a black woman and a deputy sheriff and got himself shot dead for his trouble — and whose killer was acquitted and lived out his life in peace?

Now, I’m sure many of those who screamed abuse at Ruby, or voted to acquit the murderer of Jonathan Daniels, would have insisted that they were good and faithful Christians — which takes me back to the distinction I made above, and that Renn failed to make, between “publicly professing Christianity” and “publicly being a Christian.” Those who hated Ruby may have professed Christianity, but did they live it?

If they had not professed Christianity they probably would have suffered social disapproval; if they had sought to practice it in relation to Ruby Bridges and their other black neighbors they certainly would have been excoriated — or worse. (Look at what happened to my old colleague Julius Scott, for the crime of saying that Black people should be welcomed into all-white churches.)

What David French means when he says that “It’s Always a ‘Negative World’ for Christianity” is simply this: Professing Christianity is what Renn calls a “status-enhancer” when and only when the Christianity one professes is in step with what your society already and without reference to Christian teaching describes as “being an upstanding citizen.” If you don’t believe me, try getting up on stage in an evangelical megachurch and reckoning seriously with Jesus’s teaching on wealth and poverty. Even a sermon on loving your enemies, like Ruby Bridges, and blessing those who curse you, can be a hard sell — as many pastors since 2016 have discovered. News flash: if you make a point of never saying anything that would make people doubt your commitment to their preferred social order, they’ll probably think you an upstanding citizen. (Who knew?)

There are pretty much always some elements of Christian teaching that you can get away with publicly affirming; but you can never get away with affirming them all. If American Christians sixty years ago felt fully at home in their social world, that’s because they quietly set aside, or simply managed to avoid thinking about, all the biblical commandments that would render them no longer at ease in the American dispensation. Any Christians who have ever felt completely comfortable in their culture have already edited out of their lives the elements of Christianity that would generate social friction. And no culture that exists, or has ever existed, or ever will exist, is receptive to the whole Gospel.

As I said at the outset: What’s the point even of writing this? Renn saw French’s essay, and he simply congratulated himself on getting attention. He didn’t answer any of the arguments made against his scheme, and I doubt he ever will. He’s articulated a tall tale that some people want to live by, and that seems to be good enough for him.

But there’s another reason why I doubt the usefulness of this whole debate: It doesn’t matter. Doesn’t matter one whit. I’ve said this over and over again: Whether it’s a positive world or a neutral world or a negative world or a multiverse or just a crazy old world, my job is the same: to strive for faithfulness to the Lord Jesus. What I hear him saying is, “What is all that to you? Follow me.” And following him is hard, because I am subjected to precisely the same pressures against faithful Christian witness that every other Christian faces. I’m fighting for my spiritual life here. So I'm done with this topic; my time is better spent in other ways.

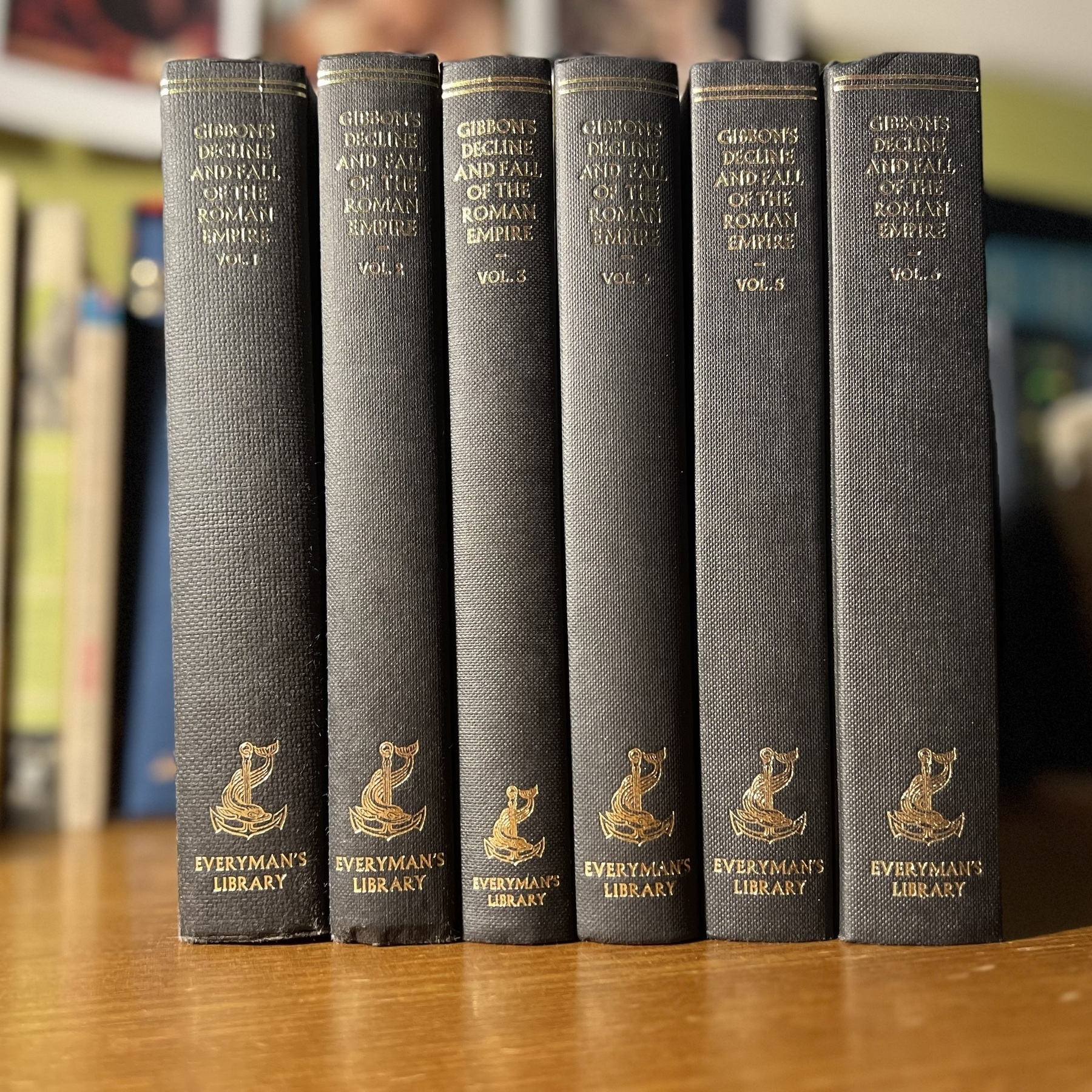

On ne peut jamais quitter les Romains.

And now, perhaps, time to reward myself with a little light reading?

Just sent off my critical edition of Auden’s The Shield of Achilles to my editors at Princeton University Press. WOW that was a lot of work, and while there’s still more to be done — editing and formatting something like this is time-consuming and difficult — this feels like an achievement. Happy Hour come my way!

stats

Just a quick reminder that the use of statistics to mislead is a never-ending thing: The Guardian, in an attempt to cast a skeptical eye on Ron DeSantis, notes that Florida “had the third-highest death toll of any US state.” Now, I am no fan of Ron DeSantis, to say the least, but come on: Florida is the third most populous state, so it would be very surprising if it didn’t have one of the highest death tolls. Plus, it has a very high percentage of elderly residents, and as we all know, the elderly are significantly more endangered by Covid than any other age group.

The relevant statistic here — if you’re interested specifically in deaths — is number of deaths per 100,000 residents, and by that measure Florida is 12th. Nothing to boast about, certainly, but better than Michigan and New Jersey and only slightly worse than Pennsylvania and New York — again, despite having an older population than any of those states. It’s also 21st in percentage of residents vaccinated.

I’m calling attention to this not because I want to defend DeSantis, but merely to note a reliable journalistic practice: If the relevant statistics don’t tell the story you want to peddle, then choose irrelevant statistics that do. Most readers won’t ask questions.

The actual story of Florida and Covid is extremely interesting, I think, precisely because the evidence doesn’t yield clear answers. Derk Thompson has a good piece on these complexities.

It’s what nihilists do.

Pevearsion

Recently I had cause to remember Gary Saul Morson’s devastating critique of the Pevear/Volokhonsky translations of Russian literature. (When you’re done with Morson’s critique you might want to go on to Janet Malcolm’s.) I decided that I need to read War and Peace again — I used to teach it occasionally, but I haven’t read it in maybe twenty years — and I picked up the beautiful Knopf hardcover of the P&V translation that someone gave me years ago.

In the second chapter we’re introduced to Princess Bolkonskaya, Prince Andrei’s young wife. Here’s that introduction in the old Louise and Alymer Maude translation:

The young Princess Bolkónskaya had brought some work in a gold-embroidered velvet bag. Her pretty little upper lip, on which a delicate dark down was just perceptible, was too short for her teeth, but it lifted all the more sweetly, and was especially charming when she occasionally drew it down to meet the lower lip. As is always the case with a thoroughly attractive woman, her defect — the shortness of her upper lip and her half-open mouth — seemed to be her own special and peculiar form of beauty.

Here’s Ann Dunnigan’s translation:

The young Princess Bolkonskaya had brought her needlework in a gold-embroidered velvet bag. Her pretty little upper lip, shadowed with a barely perceptible down, was too short for her teeth and, charming as it was when lifted, it was even more charming when drawn down to meet her lower lip. As always with extremely attractive women, her defect — the shortness of her upper lip and her half-open mouth — seemed to be her own distinctive kind of beauty.

And here is the P&V version:

The young princess Bolkonsky came with handwork in a gold-embroidered velvet bag. Her pretty upper lip with its barely visible black mustache was too short for her teeth, but the more sweetly did it open and still more sweetly did it sometimes stretch and close on the lower one. As happens with perfectly attractive women, her flaw — a short lip and half-opened mouth — seemed her special, personal beauty.

Her black mustache? The down on a woman’s upper lip is very much not a mustache. What a bizarre word-choice. Horrified, I set the book down, lovely as it is to look at, and went back to the Dunnigan translation, the friend of my youth.

But all that said: It’s remarkable, if inexplicable, how the P&V translations of Russian fiction have brought those wonderful books into the hands of many readers who otherwise might never have read them. So thanks be for that.

Finished reading: War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy. Just as I had remembered it: brilliant and bombastic, magnificent and maddening. 📚

For those of us who have been using Mastodon for a while (I started my own Mastodon server 4 years ago), this week has been overwhelming. I've been thinking of metaphors to try to understand why I've found it so upsetting. This is supposed to be what we wanted, right? Yet it feels like something else. Like when you're sitting in a quiet carriage softly chatting with a couple of friends and then an entire platform of football fans get on at Jolimont Station after their team lost. They don't usually catch trains and don't know the protocol. They assume everyone on the train was at the game or at least follows football. They crowd the doors and complain about the seat configuration.

It's not entirely the Twitter people's fault. They've been taught to behave in certain ways. To chase likes and retweets/boosts. To promote themselves. To perform. All of that sort of thing is anathema to most of the people who were on Mastodon a week ago. It was part of the reason many moved to Mastodon in the first place. This means there's been a jarring culture clash all week as a huge murmuration of tweeters descended onto Mastodon in ever increasing waves each day. To the Twitter people it feels like a confusing new world, whilst they mourn their old life on Twitter. They call themselves “refugees,” but to the Mastodon locals it feels like a busload of Kontiki tourists just arrived, blundering around yelling at each other and complaining that they don't know how to order room service. We also mourn the world we're losing.

I’m a bit concerned about micro.blog — I don’t use Mastodon — for just this reason. That’s why I wrote a few months ago, “On micro.blog, you have absolutely no incentive to flex, shitpost, self-promote, or troll. You’re there to post interesting things and/or chat with people. Nothing else makes sense.”

End-Times Tales

Venkatesh Rao — End-Times Tales:

We are drowning in a sea of reboots, reruns, and recycled stories on television and movie screens for the same reason dying people supposedly see their lives flash before their eyes. The story is ending. Despite living through arguably the greatest era of storytelling technology in history, we have no new stories to tell ourselves.

Now this is not entirely true. I’ve found the occasional fresh new story. Station 11 is an example, a lovely recent TV show, but rather tellingly, set in a post-apocalyptic world where for some reason the survivors perform budget Shakespeare reboot productions in a slightly nicer Mad Max world (really? the world ended and Shakespeare is still the source of the most interesting stories you can tell yourself?).

Yep: really. Anyone who’s ever seen a good production of a Shakespeare play — budget or otherwise — can confirm. Possibly the most powerful evening of art I have ever experienced was a performance of Measure for Measure, by a small company of actors on a bare stage surrounded by folding chairs. (Also, FYI: new performances of a play are not “reboots.”)

Also, w/r/t this: "Despite living through arguably the greatest era of storytelling technology in history, we have no new stories to tell ourselves” — replace “Despite” with “Because we are” and the sentence makes an important point.