the history of literacy

We can also kiss goodbye to the “marketplace of ideas”. This might have seemed plausible when everyone aspired to long-form, deliberative, rationalism and a broadly shared moral framework. When these are things of the past, we all absorb disaggregated, de-contextualised snippets of information at speed, our reading material rewards us for not concentrating long enough to think something through, and we can see everyone else thinking in real time on our screens?

Ah yes, I remember it well: that halcyon era when everyone sat around reading Hobbes’s Leviathan and earnestly buttonholing passersby in impassioned search for a shared moral framework.

Harrington relies heavily on a melancholy essay by Adam Garfinkle on the subject of Literacy Lost, and for people like Harrington and Garfinkle I have some questions:

Do you know anything — anything at all — about the history of literacy? About what people in any society, any society in the whole world, at any point in history, could read and did read? For instance: what percentage of people in France in 1900, or England in 1850, or China in 1800, or the U.S.A. in 1950, had ever in their lives read a single book? If they had read books, how intellectually demanding and substantive were those books? If they were assigned those books in school, did they actually do the reading? How were the books taught to them? That is, were the best qualities of those books explored in ways that were comprehensible and meaningful to the students? How common, or how rare, was the education in “deep reading” that you commend?

I ask because if you don’t have this information, then you have no business making comparative judgments between our own moment and any moment in the past. And this information is hard to find. What we do know mainly makes us want to know more. You may wish that more people read, and read good books — I certainly do — but without actual data you can’t compare us to our ancestors.

I will just say this: I think the hidden assumption in essays like Harrington’s and Garfinkle’s is that if people weren’t on social media and staring at their iPhones they’d be reading books instead. And I don’t believe for one second that that’s a safe assumption.

Currently reading: Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War by Mark Harris 📚

the final frame

James Agee, the best writer ever to review movies for a living, was never better than in his review for The Nation of William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) — for which, FYI, there will be many spoilers below. The movie concerns three returning servicemen — each struggling in his own way to find his way back into the civilian world — and the people who love them. “At its worst,” Agee writes, “this story is very annoying in its patness, its timidity, its slithering attempts to pretend to face and by that pretense to dodge in the most shameful way possible its own fullest meanings and possibilities.” He goes on in this vein for some time, and sums up his critique thus:

In fact, it would be possible, I don’t doubt, to call the whole picture just one long pious piece of deceit and self-deceit, embarrassed by hot flashes of talent, conscience, truthfulness, and dignity. And it is anyhow more than possible, it is unhappily obligatory, to observe that a good deal which might have been very fine, even great, and which is handled mainly by people who could have done, and done perfectly, all the best that could have been developed out of the idea, is here either murdered in its cradle or reduced to manageable good citizenship in the early stages of grade school.

Thus ended his review — or, rather, the first half of his review, for in the next week’s issue he returned to explain why he absolutely loved the movie. And that, friends, is Exhibit A in my case for James Agee as Top Movie Reviewer.

In that second half of his review he singles out the photography of Gregg Toland — indeed, though Agee did not know it, The Best Years would be one of Toland’s last films: he died in 1948 at the age of forty-four, and thus the film world lost its greatest cinematographer. “I can’t remember a more thoroughly satisfying job of photography, in an American movie, since Greed. Aesthetically and in its emotional feeling for people and their surroundings, Toland’s work in this film makes me think of the photographs of Walker Evans.” (Agee had, famously, collaborated with Evans on Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.)

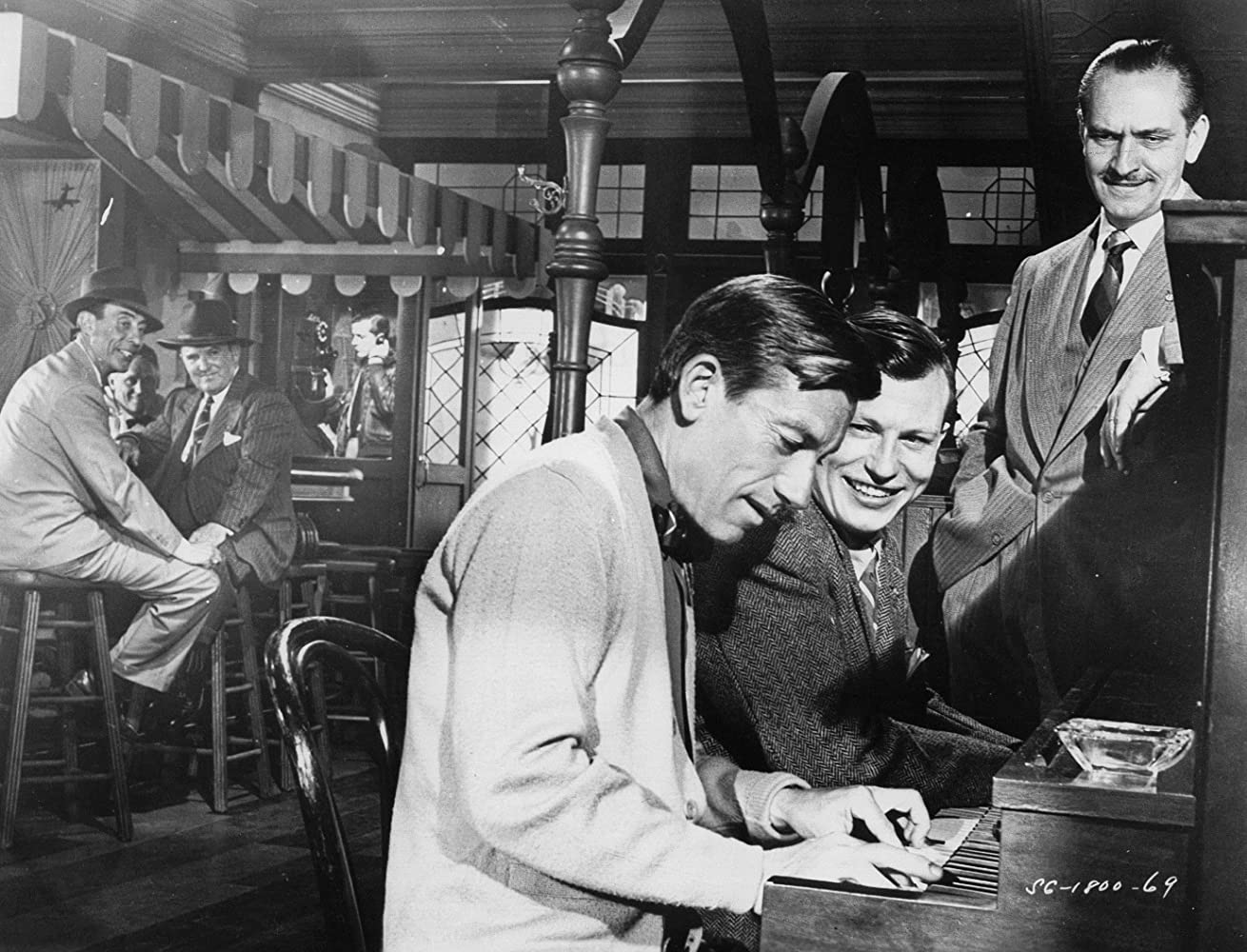

Let’s take one scene, a celebrated one, as an example of Toland’s skill — and of Wyler’s imaginative direction. Al Stephenson has a problem: his daughter Peggy is in love with another returning serviceman, Fred Derry; but Fred is married. Al asks Fred to meet him at a restaurant/bar called Butch’s, and he tells Fred not to see Peggy again. Fred is grieved, but he agrees; he’ll call her to cut all ties. As he enters the telephone booth next to the bar, Homer — the third serviceman in this story, a sailor who has lost his hands in a fire on his ship, comes in. (See the story of the actor, Harold Russell.) Butch, the owner, is his uncle, and Homer wants Al to watch him and Butch play a song on the piano — they’ve been practicing, Homer tapping the keys with his hooks and Butch filling in. Al’s mind is elsewhere, but he agrees.

The above shot appears to be a still from an alternate take, because in the movie Homer plays the melody while Butch provides bassline harmony. And in that scene Al can’t keep his eyes on the piano: he keeps looking back at Fred on the phone. But you can see here the famous Toland depth of field and a real compositional genius: Fred is a tiny figure in the back left, and yet he’s as present and vivid to the viewer as the jolly musicians in the foreground. It’s storytelling by photography, and it’s brilliant. Here’s a good clip.

There’s a scene later in the movie when Homer — who has been avoiding his fiancée Wilma because, he believes, she doesn’t understand how hard it would be to live with his disability — invites her to his room in his family’s house to see how helpless he is when he removes his prosthetic harness. (This is the one time we see Homer consciously acknowledging his limitations.) And when, instead of fleeing in horror, Wilma with infinite tenderness buttons up his pajama top, well, I let fall a manly tear.

Anyway, that clears the way for Homer and Wilma: the movie concludes with their wedding. And here the genius of Toland and Wyler comes to our aid again:

Foreground right: Homer and Wilma. Background center: Al and his wife Milly, and then, on the left, their daughter Peggy — who only has eyes for the now-divorced Fred, Homer’s best man, foreground left. (Al and Milly, like everyone else, look at the marrying couple.) And, as the scene unfolds, we discover that Fred only has eyes for her. It’s brilliant: the words of the service of Holy Matrimony unfold, and as happy as we are for Homer and Wilma, our attentions and our emotions are divided.

Teresa Wright plays Peggy, and Agee, in the second half of his review, singled her out for particular praise:

Almost without exception, down through such virtually noiseless bit roles as that of the mother of the sailor’s fiancé, this film is so well cast and acted that there was no possible room to speak of all the people I wish I might. I cannot, however, resist speaking, briefly anyhow, of Teresa Wright.… She has always been one of the very few women in movies who really had a face.… She has also always used this translucent face with a delicate and exciting talent as an actress, and with something of a novelist’s perceptiveness behind the talent. And … she has never been around nearly enough. This new performance of hers, entirely lacking in big scenes, tricks, or obstreperousness – one can hardly think of it as acting – seems to me one of the wisest and most beautiful pieces of work I have seen in years. If the picture had none of the hundreds of other things that it has to recommend it, I could watch it a dozen times over for that personality and its mastery alone.

The story of how Teresa Wright ran afoul of the studio system, and more particularly of Sam Goldwyn, and lost what could have been an extraordinary career, has been told in several different ways, most of which blame Goldwyn and the system. David Thomson, whose judgment is typically acute, seems to think that her decline was inevitable because she was “not glamorous enough to be a star,” was “relatively plain-faced.” Wright may not have been a classic beauty, but plain is not the word to describe that emotionally “translucent” face, and not much in all of movies is lovelier than her expression in the final frames of The Best Years of Our Lives, when Fred declares his love:

•

Abbas Kiorastami (1940–2016) was an Iranian film director (also a screenwriter, painter, photographer, poet) who made curious films — often seemingly simple, featuring quasi-documentary techniques, but hiding a shrewd complexity. His last film, which he had not quite completed at his death, was 24 Frames, which begins by gently, subtly animating Bruegel’s The Hunters in the Snow and then goes on to animate — always subtly, usually gently, sometimes disturbingly — a series of photographs taken by Kiorastami himself. It’s a kind of extended meditation on the very idea of a frame — a demarcated space within the confines of which we see, and see differently. See, perhaps, more vividly.

But Frame 24 is rather different. Like several of the others, it features a window. Through that window you see a night sky, and trees waving in the wind of a winter storm; in addition to the wind and rain pinging the glass, you hear, of all things, Andrew Lloyd Webber’s “Love Never Dies.” (Most the movie’s sounds are natural, though music is occasional.) In the foreground is a desk, at which a young woman is slumped over in sleep. Just above her drowsing head there’s a computer screen, and on that screen we see, in a very slow frame-by-frame advance, the last shot of The Best Years of Our Lives.

Gradually the light increases — dawn is coming — and (inch by inch) Peggy raises her gloved hand to embrace Fred, and Fred leans forward to kiss her, and down (inch by inch) goes her hat, and then: THE END.

Thus Abbas Kiorastami makes his last bow. And I find it really quite touching that his final message to us, or a big part of it anyway, is simply this: What could be more wonderful than the movies?

An Open Letter Responding to the NatCon "Statement of Principles" – The European Conservative:

In the end the National Conservative statement is neither conservative nor Christian. As critics of liberalism from both Left and Right, we must reject it. We acknowledge the importance of national cultures. We recognise the rightful place of the nation acting in defence of the common good on behalf of its citizens. But we cannot accept the idea that to fight globalisation we must uncritically embrace the nation-state as the one true political form, or the most complete community; or that the best good we can aim for is nation-states re-armed against each other, seeking their own interests in perpetual implied conflict.

Agreed wholly.

Too much of a good thing is a real problem — and in its final years, Prestige TV ran into that hard. The final season of Game of Thrones cost $15 million an episode — something fans could only dream of in terms of production value — but it couldn’t buy a plot fix. Getting back to telling stories that are well-written, around characters who are fully fleshed out, is more powerful than the biggest budget in the room. Let’s hope the next era of television understands this.

From your lips to the TV gods’ ears.

time out

I’m going to be taking a little time away from watching the Premier League, because VAR is simply ruining the experience for me. Even if it were well-implemented, VAR would be a mistake because it interferes so badly with the flow of the game and the game’s emotions — no one can celebrate anything any more without waiting to see if VAR flips the script. But it is not well-implemented. Especially in the Premier League it is more likely to result in a wrong decision than a correct one.

Of course, this is simply one element of the shockingly low level of officiating quality in the Premier League, but it greatly magnifies incompetence. I would rather live with ordinary human error than have to deal with technologically-enhanced human error. When people are already bad at their job, it’s unwise to give them even more opportunities to be bad.

I only watch footy because it’s fun, and VAR — plus other elements in the catastrophic mismanagement of English football in general and the Premier League in particular — takes away a lot of that fun. So why should I keep watching?

Currently reading: Awakenings by Oliver Sacks 📚

the end of <em>The This</em>

Start with Adam’s post about this podcast. In the podcast, Bill, Joel, and their guest Phil do a great deal to illuminate Adam’s novel The This — if you haven’t read the novel, you should, and if you have read it, you should listen to the podcast because you’ll learn a lot. I certainly did.

(And if Adam hadn’t warned me, I would have been greatly surprised to hear my name come up in the discussion! As Phil — I think it was Phil — says, Adam and Francis Spufford and I aren’t quite an -ism but we do form a kind of “vector.” I should think more about what that vector is. All I know for sure is that I greatly value my friendship with these two and don’t think that as a writer I am worthy to be mentioned in the same sentence with them.)

There are a thousand things I could say about The This, but for now — prompted by the podcast — I just want to talk about the brief final chapter. Because what I think is going on there is Adam playing the role of Alcibiades.

That final chapter says,

You are an old man, living in a European city big for its era, small by later standards, a philosopher, a teacher, a student. You, a subject of the king, have made Spirit the object of your study. You, objectively, wrote a book whose subject is Spirit. The bacterium Vibrio cholera enters your system and propagates through your gut. You experience fever, shivers, severe stomach pains. There is no diarrhoea and no swelling, and initially the physicians are hopeful. But you grow iller. You vomit gall. You cannot urinate. You begin hiccuping violently. You lie in your bed, on your side, the sheets damp from your sweat. You are shaking. You cannot stop hiccuping. You stare at the wall.

The dying old man is Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, and here you should know two things. The first is that a very similar chapter concludes Adam’s earlier novel The Thing Itself, only in that one it’s Immanuel Kant dying. Philosophers die, just as the rest of us do. The second thing you should know is Kierkegaard’s comment that Hegel’s philosophical System is a vast magnificent castle, and he lives in a little shack just outside it. Because all of us live in those little shacks, no matter how glorious our external constructions.

You are a man, you live a lonely life, you grow old and die. You are a man, you live a life rich with friends and lovers, you grow old and die.

You live, you die. Not another person. Nobody can die for you. You have to do this yourself.

That’s how it is. And here’s how else it is:

You see, love is not an abstraction. It's not a theory or a cosmic force or a slogan or any kind of diffuseness spread across the world. Love is particular. You do not love in general, you love this person, this thing, this life, you love this, this, this, this, this, and this, and this, and this loves you back. This is the only thing in the world, and it is precise and specific and real, and it is everything and infinitude.

Which brings us to Alcibiades.

Plato’s Symposium, many scholars over the years have said, — well, here’s one of them, Gregory Vlastos: the “cardinal flaw in Plato's theory” is that “it does not provide for love of whole persons, but only for love of that abstract version of persons which consists of the complex of their best qualities. This is the reason why personal affection ranks so low in Plato's scala amoris.” But as Martha Nussbaum points out, to say this is to assume that the speech of Diotima in the Symposium, narrated by Socrates and described by him as a view that has “persuaded” him, is Plato’s view. The problem, Nussbaum says, is that that’s not a safe assumption.

For after all the participants in this symposium (including Diotima-by-way-of-Socrates) have had their say about the nature of love, Alcibiades shows up, drunk and voluble, and he provides the dialogue's final account. Nussbaum: “Diotima connects the love of particulars with tension, excess, and servitude; the love of a qualitatively uniform ‘sea’ with health, freedom, and creativity.” But Alcibiades says this is all horseshit. “Asked to speak about Love, Alcibiades has chosen to speak of a particular love; no definitions or explanations of the nature of anything, but just a story of a particular passion for a particular contingent individual. Asked to make a speech, he gives us the story of his own life: the understanding of eros he has achieved through his own experience.” Asked to speak about Love, that distinguished abstraction, he instead tells stories about how much he loves Socrates — and in that way gives the lie to the account of Love by which Socrates himself has been persuaded. (Alcibiades has no “account of Love” — he doesn’t think it exists.)

Much of the The This portrays our various attempts to escape from … well, from this world, this space/time nexus, this life. Just on the pages that immediately precede the one I have quoted from we have the Hegelian Absolute, the timeless aesthetic perfection of Kubla Khan’s “stately pleasure dome,” the cyclical temporality of Joyce’s (and Vico’s) “commodious recirculation” — all ways to answer the question “Is this all there is?” with a strong firm NO. But the brief final chapter of the novel, in which Adam seems to speak in his own voice, rejects all such Systems and schemes as false comfort — or rather, as false and ultimately comfortless. What we have is not the Absolute but the This: this life, this love, and, in the end (there is an end), this death.

My view as a Christian is, of course, that they’re all wrong. (A topic for another post, which would begin by quoting Auden’s poem “Friday’s Child.”) But Adam is less wrong than those who seek to escape the this. He sees that, if we would understand our quotidian vale of tears and our place in it, we need poems and novels — accounts of our particulars — more than we need Systems “or any kind of diffuseness spread across the world.”

And maybe that’s the vector where Adam and Francis and I meet: Love calls us to the things of this world.

When we are caked with the mud of political struggle, and tired of Pyrrhic victories that seed new hatreds, and frightened by our own capacity for contempt, the way of life set out by Jesus comes like a clear bell that rings above our strife. It defies cynicism, apathy, despair and all ideologies that dream of dominance. It promises that every day, if we choose, can be the first day of a new and noble manner of living. Its most difficult duties can feel much like purpose and joy. And even our halting, halfhearted attempts at faithfulness are counted by God as victories.

God's call to us while not simplifying our existence does ennoble it. It is the invitation to a life marked by meaning. And even when, as mortality dictates, we walk the path we had feared to tread, it can be a pilgrimage, in which all is lost, and all is found.

Before such a consummation, Christians seeking social influence should do so not by joining interest groups that fight for their narrow rights and certainly not those animated by hatred, fear, phobias, vengeance or violence. Rather, they should seek to be ambassadors of a kingdom of hope, mercy, justice and grace. This is a high calling and a test that most of us (myself included) are always finding new ways to fail. But it is the revolutionary ideal set by Jesus of Nazareth, who still speaks across the sea of years.

Listening to: Mingus Ah Um by Charles Mingus ♫

There’ll always be an …

The-Sick-Soul-of-Europe Parties

In 1963 Pauline Kael — a freelance essayist, five years before her gig at the New Yorker — published an essay in the Massachusetts Review about some then-recent and then-widely-discussed European films. It’s a very interesting and (I think) convincing essay, animated by the strong views about what movies ought to be that would later make Kael notorious, but without the laying-down-the-law tone that makes so much of her later writing frustrating to read. She wasn’t yet “Pauline Kael of the New Yorker,” she was just another writer in a relatively obscure literary quarterly. Here’s how it starts:

La Notte and Marienbad are moving in a new filmic direction: they are so introverted, so interior that I think the question must be asked, is there something new and deep in them, or are they simply empty? When they are called abstract, is that just a fancy term for empty? La Notte is supposed to be a study in the failure of communication, but what new perceptions of this problem do we get by watching people on the screen who can't communicate if we are never given any insight into what they would have to say if they could talk to each other?

I think she is asking precisely the right questions here and leading her reader towards the right answers. The problem is not so much that these films are pretentious — though Lord knows they are — but that they are empty. They are empereurs sans vêtements.

Later:

In La Notte we are people for whom life has lost all meaning, but we are given no insight into why. They're so damned inert about their situation that I wind up wanting to throw stones at people who live in glass houses. At a performance of Chekhov's Three Sisters, only a boob asks, "Well, why don't they go to Moscow?" We can see why they don't. Chekhov showed us why these particular women didn't do what they said they longed to do. But in movies like La Notte or Marienbad, or, to some degree, La Dolce Vita the men and women are not illuminated or ridiculed — they are set in an atmosphere from which the possibilities of joy, satisfaction, and even simple pleasures are eliminated. The mood of the protagonists, if we can call them that, is lassitude; there is almost no conflict, only a bit of struggling — perhaps squirming is more accurate — amid the unvoiced acceptance of defeat. They are the post-analytic set — they have done everything, they have been to Moscow and everywhere else, and it's all dust and ashes: they are beyond hope or conviction or dedication. It's easy enough to say “They are alienated; therefore, they exist,” but unless we know what they are alienated from, their alienation is meaningless — an empty pose. And that is just what alienation is in these films — an empty pose; the figures are cardboard intellectuals — the middle-class view of sterile artists. Steiner's party from La Dolce Vita is still going on in La Notte, just as the gathering of bored aristocrats in La Dolce Vita is still going on in Marienbad.

Of the three films, Last Year at Marienbad is the most visually interesting, and visual interest is the only kind there can be in movies of this sort. But the interest doesn’t last long. This three-minute video essay about the film tells you all you need to know about it, I think.

Karl could have ended up in a kind of intellectual dead-end: she despised the emptiness of so much New European Cinema, and loved the rough vigor of Old Hollywood … but the world of movies is always mainly about the new, and Old Hollywood was clearly dying. (The amount of absolute trash that the studios cranked out through most of the Sixties is astonishing.) As Mark Harris shows in his brilliant book Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood, in 1967 — the year of Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate — the great pivot happened. And it was her essay in praise of Bonnie and Clyde that landed Kael her job at the New Yorker.

Watching Eurobasket this morning (which is awesome) and I just saw a European sports website identifying Luka Doncic as a player for “Maverick Dallas” – by analogy with Dynamo Kiev or Lokomotiv Moscow, I suppose. So that’s what I’m calling the team from now on: MAVERICK DALLAS.

Currently reading: Mike Nichols: A Life by Mark Harris 📚

wait, what?

I started telling people what a terrific writer Brian Phillips is back in 2008, when he wasn’t yet even a gleam in Bill Simmons’s eye, and since then I’ve written for his old site The Run of Play, we’ve eaten lunch together in Harvard Square, and once we joined forces to confront an enraged lunatic photographer on Flickr. When you’ve been through the wars like that, it forms a bond, you know? So I’m as proud as a slightly obnoxious big brother to learn that he’s a fantastic podcaster too.

I have enjoyed this whole series, but now that we’re at Dennis Bergkamp … well. My feelings about Dennis Bergkamp are strong. Watch the YouTube clips Brian has lined up there, and you’ll see why.

I’m going to make one point about that goal against Argentina — the ostensible subject of Brian’s episode — and then a more general point. Brian describes the goal well: the long, long pass from Frank de Boer; Bergkamp’s leaping first touch that kills the ball; the subtle pullback from the right side of his body to the left that sends Roberto Ayala flying. But then there’s the shot itself. Bergkamp can’t take the time to shape his body to take a proper shot, with either foot; all he has time for is a toepoke, a quick insouciant flick of the ball that looks a little like a dancer doing the can-can. And yet the ball just arrows into the roof of the net. The first touch and the pullback came from masterful technical skill; that shot from sheer imagination.

Thus my more general point: As Brian hints, Bergkamp’s distinctive style of play was simply made for YouTube, because all of Bergkamp’s greatest plays leave you saying, Wait … what? What did I just see? Let me rewind that.

Consider the two examples Brian gives near the end of that post (which transcribes the episode). On that assist to Freddie Ljungberg vs. Juventus the commentator doesn’t even mention the pass, because I don’t think he has any idea what has just happened. And to be fair, it’s almost impossible to see on a first viewing. You have to run it back and look again, because it’s that imagination again, that Bergkampian sublime. If you’re commenting on the match you just end up saying “Terrific goal from Ljungberg!” or the like — because the actual finish is something that happened in the world of space-time as we know it. The pass, by contrast, happens somewhere else.

The famous Newcastle goal is even weirder. I’ve seen it a hundred times, and every time I see it I say, “Wait … what?” What precisely did he just do? Also, how did he ever think of that? “Ah, when the ball gets to me I’ll just flick it to my right and behind me, while simultaneously pivoting to my left, so that the ball and I will meet in an enveloping pincer movement that will leave the defender and keeper helpless!” As Brian says: Ladies and gentlemen, Dennis Bergkamp!

But I want to look at one more, this one:

Again, the perfect first touch, followed by a little private game of keepy-uppy, and then the clinical finish. But what I love most about this is the reaction of the defender, who had been right there, who had been in perfect position, who had done his job … and yet look at what happened. As the ball goes into the net his hands fly up to his head: “Wait … what??”

Letter from Martin Luther King Jr. to Clarence Jordan and the people of Koinonia Farm in Georgia; from a fine reflection on Jordan by Starlette Thomas.

The original Yale Book of Quotations (2006), on which this new edition is closely based, was always a spunkier affair than the Oxford Dictionary. It had the North American bias implied by its title.

As opposed to books with “Oxford” in the title, which of course have no bias at all.

Stanley Fish, How Milton Works:

To those in whose breast it lodges, the holy is everywhere evident as the first principle of both seeing and doing. If you regard the world as God’s book before you ever take a particular look at it, any look you take will reveal, even as it generates, traces of his presence. If, on the other hand, the reality and omnipresence of God is not a basic premise of your consciousness, nothing you see will point to it and no amount of evidence will add up to it. You will miss it entirely, as Mammon [in Paradise Lost] does when all he can see in the soil and minerals of hell is material for a home-improvement project, one that will make up for the loss of heaven: “Nor want we skill or art, from whence to raise / Magnificence; and what can Heav’n show more?” He’s not kidding; he really means it. As far as he can see (a colloquialism I want to take very seriously), there is nothing more to see than the phenomena his art and skill will be able to produce; and those phenomena will bring heaven back to him because he never knew what it was in the first place…. Had he truly known heaven, he could not have moved away from it, for it would have been “a heaven within” (as it is for Abdiel, whose physical removal to the North leaves him unchanged in his essence); and were he now to know it by realizing what he had lost and could not replace by feats of construction, he would no longer have lost it, for its reality would be animating him even in exile and he would be in the position the Elder Brother imagines for his virtuous sister: “He that has light within his own clear breast / May sit i’th’ center, and enjoy bright day” (Comus, 381–382).

Currently listening: summerteeth by Wilco 🎵