I have always loved rain, but not until I moved to Texas did I really LOVE rain.

Currently reading: Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood by Mark Harris 📚

40-year report

When I first started teaching college students, at the University of Virginia forty years ago, I discovered that

- A few students were right on my wavelength and connected with almost everything I was trying to do: they worked hard, read carefully, wrote well;

- A few students didn’t connect with anything I tried to do, obviously didn’t want to be in the class, and did the least work they could, which means that they didn’t improve as readers or writers;

- The great majority of students weren’t either hostile or enthusiastic; they probably didn't especially want to be in my class, but they were cheerful and cooperative and willing to give it a shot, within reason; I and my class weren’t at the top of their list of priorities, but they weren’t going to blow me off either, and over time they got at least a little better at both reading and writing.

Forty years later … nothing has really changed. I often read lamentations of older teachers who write as though at the beginning of they careers they taught roomsful of Miltons-in-the-making and are now reduced to managing the inmates of Idiocracy. To me, these reports might as well come from Mars.

With some exceptions, of course, I really liked the students I taught in 1982 and I really like the ones I teach now. I don’t think they are noticeably worse at reading or writing than they were all those decades ago, though they’re less likely to have a lot of experience with the standard academic essay (introduction, three major points, conclusion) — which I do not see as a major deficiency. That kind of essay was never more than a highly imperfect tool for teaching students how to read carefully and write about what they have read, and, frankly, I believe that over the years I have come up with some better ones. As for reading: I often assign big thick books and quiz my students regularly to make sure they’re keeping up; some of them struggled with that way back then, and some of them struggle now; and I have always had students thank me for making them read big books that they probably would have given up on if I hadn’t been holding them accountable.

Sometimes I have gotten to know students well, learned about their hopes and fears, offered advice when I had some to offer, and offered affectionate support when I had no advice. Those have been very good experiences indeed. And then …

Around five years ago I was teaching Middlemarch in an upper-divisional class that had some science majors in it. One of them was a young woman about go to on to graduate school in physics — she was a star in the making who had already co-authored papers with her Baylor profs — and for her the academic study of literature was something like a third or fourth language. She never spoke up in class, and I couldn’t read her face very well. But then, at the end of our last day on the novel, I was stuffing my book and notes into my backpack as she was walking out. She veered over to me, put one hand on her heart, opened her eyes very wide, and silently mouthed: This book!

That’s why I’m in the game, people.

open letter

Politics is exceptionally difficult. I mean, think about it: what could be more complex and challenging and fraught with landmines than the attempt to figure out ways for all of us, with all our differences, to live in some semblance of just harmony together. Moreover, as we have seen repeatedly throughout human history, even the most well-intentioned and well-informed of policies can have unfortunate or even disastrous unforeseen consequences. (What William Goldman said about the movies is even more true of politics: “Nobody knows anything.”) And, to add to all that: I have no specialized political knowledge or experience. Sure, like everyone else, I have my preferences and inclinations and aversions, but there is absolutely no reason for me or for anyone else to think that my opinions have any particular weight or value. So, in public I will remain largely silent about political matters, and will focus instead on writing and speaking within my areas of expertise. In that way I hope to provide some public service while also avoiding the dangers of darkening counsel by words without knowledge.

Yours sincerely,

No academic ever

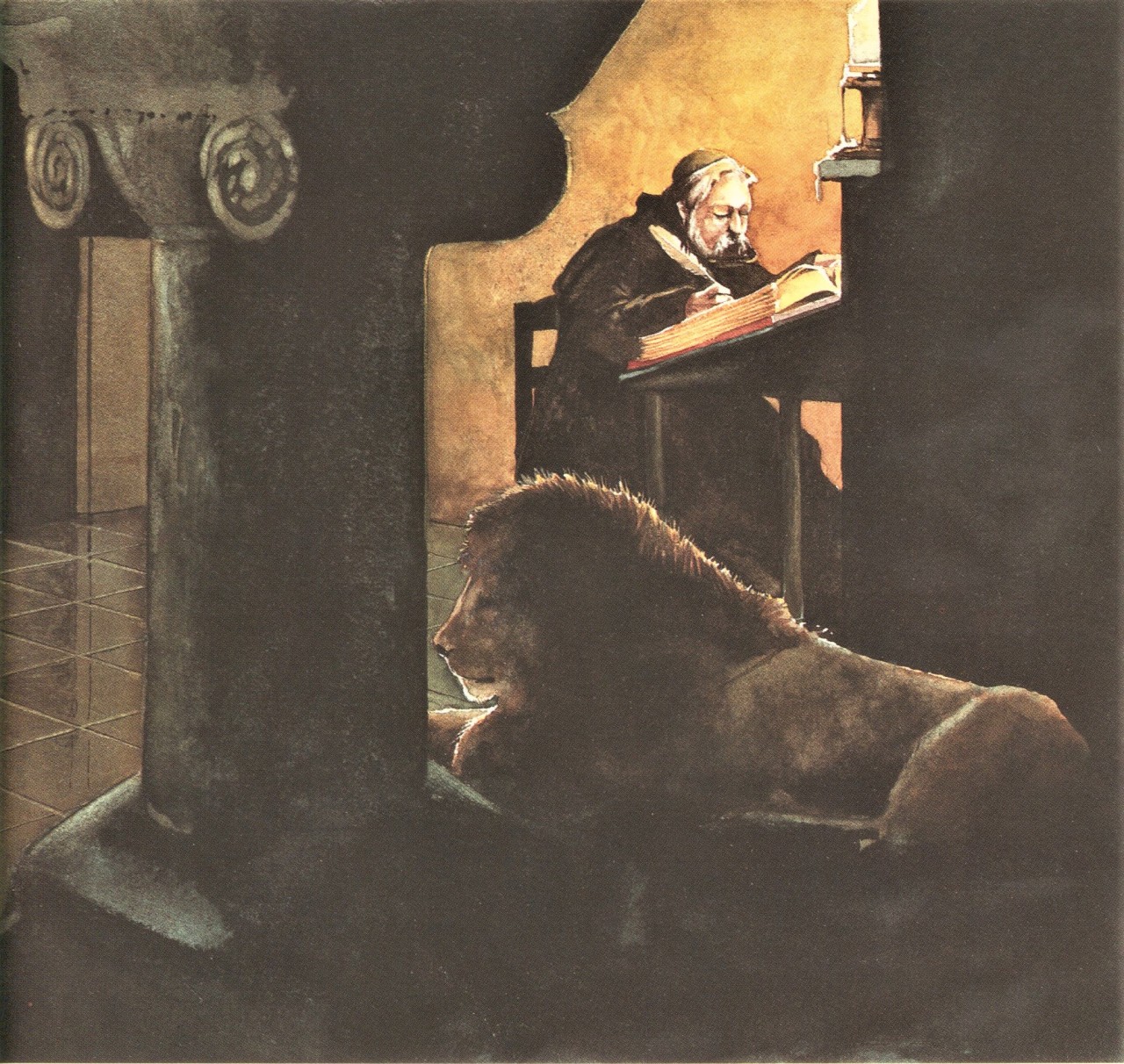

Barry Moser, St. Jerome and the Lion

Currently reading: A Light in the Dark: A History of Movie Directors by David Thomson 📚

quote unquote

I have no idea what is actually going to happen before I die except that I am not going to like it.

— W. H. Auden, 1966

How Moral Panic Has Debased Art Criticism - Alice Gribbin:

Artwords are not to be experienced but to be understood: From all directions, across the visual art world’s many arenas, the relationship between art and the viewer has come to be framed in this way. An artwork communicates a message, and comprehending that message is the work of its audience. Paintings are their images; physically encountering an original is nice, yes, but it’s not as if any essence resides there. Even a verbal description of a painting provides enough information for its message to be clear.

This vulgar and impoverishing approach to art denigrates the human mind, spirit, and senses. From where did the approach originate, and how did it come to such prominence? Historians a century from now will know better than we do. What can be stated with some certainty is the debasement is nearly complete: The institutions tasked with the promotion and preservation of art have determined that the artwork is a message-delivery system. More important than tracing the origins of this soul-denying formula is to refuse it — to insist on experiences that elevate aesthetics and thereby affirm both life and art.

I wonder if this move is driven, in large part, by the demands of the ancient warfare between art and criticism: the critical defining of art as a message-delivery system is a way of saying that art merely does what criticism does, just not as well. For critics are habitually in the message-delivery business.

two quotations on memory holes, present and future

Abstract

Technological and economic forces are radically restructuring our ecosystem of knowledge, and opening our information space increasingly to forms of digital disruption and manipulation that are scalable, difficult to detect, and corrosive of the trust upon which vigorous scholarship and liberal democratic practice depend. Using an illustrative case from China, this article shows how a determined actor can exploit those vulnerabilities to tamper dynamically with the historical record. Briefly, Chinese knowledge platforms comparable to JSTOR are stealthily redacting their holdings, and globalizing historical narratives that have been sanitized to serve present political purposes. Using qualitative and computational methods, this article documents a sample of that censorship, reverse-engineers the logic behind it, and analyzes its discursive impact. Finally, the article demonstrates that machine learning models can now accurately reproduce the choices made by human censors, and warns that we are on the cusp of a new, algorithmic paradigm of information control and censorship that poses an existential threat to the foundations of all empirically grounded disciplines. At a time of ascendant illiberalism around the world, robust, collective safeguards are urgently required to defend the integrity of our source base, and the knowledge we derive from it.

Science must respect the dignity and rights of all humans — Nature:

Advancing knowledge and understanding is a public good and, as such, a key benefit of research, even when the research in question does not have an obvious, immediate, or direct application. Although the pursuit of knowledge is a fundamental public good, considerations of harm can occasionally supersede the goal of seeking or sharing new knowledge, and a decision not to undertake or not to publish a project may be warranted.

Consideration of risks and benefits (above and beyond any institutional ethics review) underlies the editorial process of all forms of scholarly communication in our publications. Editors consider harms that might result from the publication of a piece of scholarly communication, may seek external guidance on such potential risks of harm as part of the editorial process, and in cases of substantial risk of harm that outweighs any potential benefits, may decline publication (or correct, retract, remove or otherwise amend already published content).

(N.B.: Nature’s policy does not address misinformation: the journal does not propose to be vigilant against falsehood, but rather to be vigilant against actual knowledge that risks harm to … well, to whatever groups Nature prefers to see unharmed.)

Currently reading: Making Movies by Sidney Lumet 📚

ELEMENT ANTYSOCJALISTYCZNY

While I’m in Covid-induced memory mode… This is my beloved, circa 1981, with what I think is her first selfie. She had been listening to a public radio show featuring Ben Wattenberg in which Wattenberg explained that the Communist government in Poland had been cracking down on “antisocialist elements” — which led to dissidents making shirts on which they proudly identified themselves as just that: ELEMENT ANTYSOCJALISTYCZNY. So Teri found an address and wrote to Wattenberg to see if he could get her such a shirt, and behold — this selfie. She still has the shirt, by the way, though that old Minolta SLR is long gone.

heads up

Might be kinda quiet around here for a few days — I (finally) have Covid, and feel like a dim bulb. A stuffy, achy, coughy dim bulb. Though if it gets no worse than this I will think I got off fairly easy.

I hope the posts earlier today about Oliver Sacks and (especially) Fred Buechner are reasonably clear, though I might not be the best judge of that.

One more thing: I can’t be absolutely precise about the timing because I don’t have access to a 1982 University of Virginia academic calendar, but: I taught my first class forty years ago this week. Which is an anniversary to remember.

Okay, TTFN.

Remembering Fred Buechner

My wife Teri and I first met Fred Buechner in 1984, when he came to Wheaton College for a ceremony acknowledging the donation of his papers to the college’s Special Collections. We only spoke briefly at that time, and my chief memory of our conversation is Fred’s passionate impromptu defense of Anthony Trollope as a great and deep novelist – not the relatively lightweight storyteller, the maker of fictional comfort food, that he is often said to be. I had not read Trollope at that time, and when I first sat down with his books I was glad to recall Fred’s words – they made me a better reader of that much-loved but still-underrated writer.

The next year Fred returned to Wheaton for an eight-week stint as a visiting professor, an adventure that he describes in the third of his series of brief memoirs, Telling Secrets. A couple of years earlier he had spent a term teaching homiletics at Harvard Divinity School, an experience he found always perplexing and sometimes discouraging:

Whatever may have bound my students together elsewhere in the way of common belief or commitment, I was much more aware of what divided them. It did not take me long to discover early in the game, as you might have thought I would have known before I came, that a number of them were Unitarian Universalists who by their own definition were humanist atheists. One of them, a woman about my age, came to see me in my office one day to say that although many of the things I had to teach about preaching she found interesting enough, few of them were of any practical use to people like her who did not believe in God. I asked her what it was she did believe in, and I remember the air of something like wistfulness with which she said that whatever it was, it was hard to put into words. I could sympathize with that, having much difficulty putting such things into words over the years myself, but at the same time I felt somehow floored and depressed by what she said. I think things like peace, kindness, social responsibility, honesty were the things she believed in – and maybe she was right, maybe that is the best there is to believe in and all there is – but it was hard for me to imagine giving sermons about such things. I could imagine lecturing about them or writing editorials about them, but I could not imagine standing up in a pulpit in a black gown with a stained glass window overhead and a Bible open on the lectern and the final chords of the sermon hymn fading away into the shadows and preaching about them. I realized that if ideas were all I had to preach, I would take up some other line of work.

This experience was still fresh in Fred’s mind when he came to Wheaton – and if you want to know what he thought about that event, well, you should read Telling Secrets, which is by any measure a beautiful book and more than worth reading even if you don’t care a fig about Harvard or Wheaton.

Teri and I spent a good bit of time with Fred during that eight-week period: we went to the Wheaton Theater to see Return to Oz (the Oz books were always totemic and iconic for Fred); on weekends we traveled into Chicago to eat at fancy restaurants, meals for which Fred always paid, referring to himself as “the rich man from the east”; and two or three times we ate at a local restaurant that he somewhat comically grew attached to. It was called the Viking, and was a more or less standard Midwestern steakhouse with one peculiarity on the menu: they served a spinach salad that they would flame at your table. At one point a salad was set afire directly behind Teri and me, and we flinched forward in our seats as the flames warmed our necks, which caused Fred to lean over and whisper conspiratorially to Teri: “This is a dangerous restaurant.” (Fred loved Teri, in part because she was the same age as one of his daughters – he and his wife Judy had three daughters – and he would occasionally say to me, “I only put up with you because of your wife.”)

A year or so later, I think, the Viking was badly damaged in a fire, and since nothing could have been less surprising, I hastily wrote Fred a letter about it. The relevant portion of his reply:

And the fiery fate of the Viking! I can only hope that by now it is back in commission again. I remember with extraordinary pleasure – together with so many other things about my Wheaton weeks – my suppers there. Steak, medium rare, with a baked potato and salad, and a glass or two of red wine for the stomach’s sake. I would always bring a book to read as I ate, but most of the time I would just sit there feasting my eyes on my fellow diners and the flames from the various chafing dishes ablaze around me. Had I only thought to warn them.

On several occasions that semester I got to hear Fred read from his own work, and he was an absolutely marvelous reader. His writing was, I think, and this is true of most of the best writers, emergent from speech. He loathed excessive punctuation, and a sentence didn’t have to have a lot of punctuation for him to consider it excessive: he wanted the pauses and emphases to be clear from the words. Read that passage from Telling Secrets aloud; it’s a marvel of timing and rhythm, like the phrasing of a great jazz singer. Or consider this passage from what I think is his best novel, Son of Laughter – a retelling of the story of Jacob, who refers to YHWH as the Fear:

The unclean blood no longer clung to our hands, but the small gods clung still to our hearts. They clung with silver fingers, with fingerless hands of wood and baked clay. Like rats, the gods gibbered in our hearts about the rich gifts they have for giving to us. The gods give rain. The swelling udder they give and the sweet fig, the plump ear of grain, the ooze of oil. They give sons. To Laban they gave cunning. They give their names as the Fear, at the Jabbok, refused me his when I asked it, and a god named is a god summoned. The Fear comes when he comes. It is the Fear who summons. The gods give in return for your gifts to them: the strangled dove, the burnt ox, the first fruit. There are those who give them their firstborn even, the child bound to the altar for knifing as Abraham bound Isaac till the Fear of his mercy bade the urine-soaked old man unbind him. The Fear gives to the empty-handed, the empty-hearted, as to me from the stone stair he gave promise and blessing, and gave them also to Isaac before me, to Abraham before Isaac, all of us wanderers only, herdsmen and planters moving with the seasons as gales of dry sand move with the wind. In return it is only the heart’s trust that the Fear asks. Trust him though you cannot see him and he has no silver hand to hold. Trust him though you have no name to call him by, though out of the black night he leaps like a stranger to cripple and bless.

Fred was one of the great prose stylists of his era, and while I don’t write like him — I don’t have the skill, and in any case the sorts of things that I write about and the ways that I write about them demand a different style than he developed — I’ve learned a great deal about the writing of prose from him. He made me think about prose in a different way than I ever had before, and if I have ever managed to write well, I think I owe a lot of that success to Fred.

But the most important lessons that I learned from Fred, lessons I’m still learning from him, arise from his temperament as a Christian. Not his beliefs, specifically, but his manner of approaching God and approaching the world. It was open-minded, to be sure, but more than that it was open-hearted, and continually aware of the ways that the world, like the Fear who made the world, can both hurt us and bless us. (He and I shared a great love for the passage in Anna Karenina in which Kitty gives birth to her first child and Levin, the new father, immediately thinks: Now the world has so many more ways to hurt me.) Fred was always fascinated by the many ways the God who loves us can use both the wounds and the blessings to form and shape our very being. Fred manifested – and in some ways this is even more evident from his personality than from his writing – a kind of gently ironic but faithful and hopeful bemusement. It’s very hard to describe, but I found it enormously winning, and the absence of it from the world is I think a real loss.

We hadn’t often been in touch in the past fifteen years. Once, I sent him a copy of W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn, a book I deeply love and that I felt sure Fred would also love. He wrote back to tell me that he had read it and indeed loved it, though he went on to say that he had absolutely no idea what it was about. Correspondence languished after that, alas. I thought many times over the last few years of writing to him, but I didn’t know what kind of shape he was in, and I didn’t know whether our relationship had ever been close enough to deserve that. I now regret not having made connection, as one does.

The last time Teri and I saw Fred and his quietly gracious wife Judy was at Calvin College some years ago, where Teri and Judy talked about their mutual love of horses. As we parted Judy asked Teri to come and ride with her sometime at their farm in Vermont, and of course that never happened, because Teri and I are the sort of people who are afraid of imposing, and fear that that sort of invitation might be pro forma rather than genuine. Now of course we wish we had put it to the test.

I am so thankful for Fred’s life and work and example, and I will miss him, and the world will miss him. May you rest in peace, good and faithful servant.

One more tiny thing: One autumn day in 1985, Fred came to our shabby apartment because he wanted to see my recent acquisition: an original Macintosh, complete with an ImageWriter printer. (My mom, who worked in a bank, had arranged a loan for me — the two items cost nearly three thousand bucks, as much as a car, and a fifth of my annual salary. But I had a dissertation to write and a determination not to take forever doing it.) Fred was quite taken with these devices, and ordered his own when he got back to Vermont; so I always smiled when I got ImageWriter-printed letters from him, like this one:

speed revisited

Consider this a kind of follow-up to my post from some weeks ago on moving at the speed of God.

I’ve been reading Lawrence Wechsler’s And How Are You, Dr. Sacks? — which is just fascinating. But for today I want to talk about something specific that comes up near the end of the book: the question of whether Sacks was a reliable narrator, whether his fantastic “clinical tales,” as he calls them, were just that, fantasies. Many of his fellow neurologists simply don’t trust him, and Wechsler gives over an entire chapter to their doubts. But Wechsler also provides the testimony of people who worked closely with Sacks, and among the most interesting of these is Margie Kohl (later Marjorie Kohl Inglis).

Kohl’s view is that many of the neurologists who are skeptical of what Sacks discovered simply aren’t patient enough to investigate as he investigated. “Most neurologists are so stuck in their checklists and their Medicare-mill fifteen-minute drills that they miss everything; Oliver missed nothing.”

Kohl worked with Sacks when he was treating the victims of encephalitis that he later described in his famous book Awakenings — perhaps also his most controversial book, because the changes he describes these people experiencing seem, to many neurologists, too dramatic to be true. So Wechsler asked Kohl whether Sacks had invented his patients’ spectacular response to the drug called L-DOPA, and she replied:

I know the charge is not true, and I was there. Sure, he would occasionally attribute higher vocabulary to some of the patients — Maria, for instance, was uneducated and he made her language flow, but this was as much as anything out of respect for her, an honoring and cherishing of her — and in a wider sense he embellished nothing. And many of the patients did talk fluently and with great subtlety.

But you had to be willing to sit at the bedside and listen. They didn't just up and tell you these things. You had to establish rapport and a context.

With Leonard, for instance, most people had never gotten to him because (and I am speaking here of the years before L-DOPA) they wouldn't spend the time with him: He was very slow, each letter might take a minute for him to spell out on his board, and everyone else would limit themselves to yes or no questions. But Oliver sat it out.

Leonard L. is one of the major characters in Awakenings — also one of its saddest stories. As you can tell from Kohl’s comment, for decades Leonard could not speak, but could only write his thoughts out with great labor on a chalkboard — which is why the neurologists who treated him would only ask him Yes/No questions: that way they only had to wait long enough to see that he was making a “Y” or an “N.” But Sacks asked him questions that required much longer answers — and then “sat it out” as Leonard wrote on his board. Can you even imagine what this meant to Leonard? — to have someone give him encouragement to say what he needed to say, no matter how long it took?

Some years after the book’s publication, when he learned that Leonard had died, Sacks wrote a letter to his mother, which concludes with these moving paragraphs:

Only the passage of years can give one perspective — and it comes to me that I have known Leonard — and you — for fifteen years; which is quite a long time in anyone's life. What I felt in 1966 I felt more strongly every year — what a remarkable man Leonard was, what courage and humour he showed, in the face of an almost life-long heart-breaking disease. I tried to give form to this feeling when I wrote of him in Awakenings … but was conscious of how inadequate and partial this was: perhaps even more so to you, for you were such a life-giver to him … Perhaps this only became clear to me in the years afterwards….

I have never had a patient who taught me so much — not simply about Parkinsonism, etc., but about what it means to be a human being, who survives, and fully, in the face of such affliction and such terrible odds. There is something inspiring about such survival, and I will never forget (nor let others forget) the lesson Leonard taught me; and, equally, there has been something very remarkable about you, and the way in which you dedicated so much of your strength and life to him … he could never have survived — especially these last years — without your giving your own life-blood to him…. You too are one of the most gallant people I know.

Now Leonard has gone, there will be a great void and a great grief — there has to be where there has been a great love. But I hope and pray that there will be good years, and real life, ahead for you yet … you have a great vitality, and you should live to a hundred! I hope that God will be good to you, and bless you, at this time, give you comfort in your bereavement, and a kind and mellow evening in the years that lie ahead.

With my deepest sympathy and heartfelt best wishes,

Oliver Sacks

Sacks loved Leonard, and admired him, and he could love and admire him only because he knew him, and he could only know him by spending a great deal more time with him than anyone else would have — as in more time by a factor of fifty. Checklists are sometimes absolutely necessary; but at other times they and a daily schedule of “rounds” are the worst tools a doctor can have. Sacks was willing to move at the speed of Leonard — at what felt like no speed at all, what felt like stasis — and as a result “Oliver missed nothing.” Having missed nothing, he garnered a testimony that he could pass on to his readers. And in that way, sisters and brothers, he moved at the speed of God.

Currently reading: And How Are You, Dr. Sacks?: A Biographical Memoir of Oliver Sacks by Lawrence Weschler 📚

W. H. Auden, writing in The Griffin (February 1959):

For several centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire, Greek culture was unknown to the West except through the Latin culture it had permeated. When the humanists of the Renaissance made contact with its literature at first hand, their admiration led them to believe that, by imitation, they could turn themselves into Greeks. This belief was fantastic, but the intense study of a past culture which it inspired initiated a new process of intellectual discovery. It is not really his technology which distinguishes “modern” man from his predecessors, but his historical consciousness. The discovery of the mind by itself is discovery in a unique sense. To discover something normally means to become aware or to understand the nature of something which was already there waiting to be discovered, but the discovery of the intellect is an act of creation: “The self does not come into being except through our comprehension of it.” The most significant intellectual advance of the last two hundred years has been the discovery that by reliving the stages through which we have come to be what we are, we change what we are.

Thesis: Our current lack of historical consciousness — indeed, it is a refusal of historical consciousness, a shunning of the past — causes a loss of what the rise of historical consciousness provided to us: an understanding of how we came to be what we are. The fully presentist mind can have no self.

More on this possibility in future posts….

An annoyance: Online security systems these days assume that everyone is surgically attached to their phone.

the publishing monoculture

Why We Need Independent Publishers:

The process of creating art and then asking others to assign it a somewhat made-up market value is admittedly one of the most bizarre aspects of a writer’s job, for all that it is necessary for those of us trying to make a living. It seems likely that the math could prove even less favorable to authors — especially debut authors, especially those from marginalized backgrounds — if smaller publishers cannot thrive and maintain their independence. Indies routinely bet on daring literature and play a crucial role in launching, building, and sustaining the careers of writers whose work we need. The work being published by these presses — places such as Tin House, Graywolf, Milkweed Editions, Coffee House, Akashic Books, New Directions, Melville House, and The Feminist Press — is one thing that gives me hope for the future of publishing. Whether or not one industry giant is ultimately able to acquire another, whether we end up with a Big Five, a Big Four, or a Big One and Everyone Else, the publishing ecosystem needs strong, flourishing independent presses — and authors and readers do too.

Nicole Chung is right. And (as a Penguin/Random House author) I really hope the proposed merger with Simon & Schuster is quashed. Indeed, I’d love to see a devolution in the publishing industry. Back in the 1970s, when I worked as a receiving clerk in a bookstore, shipments came from everywhere; it seemed that we got books from a thousand presses — though maybe it was just a hundred — all of which had their own niche, their own style, their own mission. The homogenization of the publishing world is sad, and, like the dominance of a handful of social media companies, bad for our intellectual and moral environment. Down with monocultures!

So, cue Ted Gioia:

When I was publishing my first three books … my editor had my trust and vice versa. We worked together closely as individuals on every issue, from writing to marketing, even down to the tiniest details. I knew publishing was a business, even back then, but it didn’t feel like one. That started to change in the new millennium, and every aspect of that downstream process became more acutely corporatized.

Fortunately, the rest of the world has changed too, especially technology. And authors have options that didn’t exist years ago. Or, in some instances, they have options that didn’t even exist just a few months ago.

Substack is one of those options.

So I’ve decided to publish my next book on Substack.

This is interesting to me, because Ted and I have similar writing trajectories: We’re about the same age, we’ve published roughly the same number of books over the same number of years, and we’re both “midlist” writers (though he has more consistently been at the upper end of the midlist than I have). I’ve also experienced the “corporatizing” that he speaks of, but perhaps in slightly different ways: the chief factor making my life unpleasant has been the outsourcing of much of the editorial business to freelance copyeditors and production companies, which has led to extreme problems with quality control. (One reason I enjoy working with Princeton University Press is that they still keep most elements of the process in-house — though the freelance copy-editor for my Book of Common Prayer biography helped me allow some embarrassing errors to slip through.) I have several books that I want to write but I find myself thinking, mournfully: Do I really want to go through all that yet again?

I tell you, Ted’s post makes me fret — and not for the first time — about all the money I might be leaving on the table by not moving to Substack. But I love being on the open web; and in any case I would only have a fraction of the subscribers that Ted has. (I just don’t know how small a fraction: 1/10? 1/100? 1/1000?) I think I’m better off where I am. Probably. Maybe.