“Repeated, long-term exposure to standing also has been implicated in the development of serious health problems.” Exposure to standing? Like, being in the same room with a standing person?

The Constitution Is Broken and Should Not Be Reclaimed:

Americans could learn simply to do politics through ordinary statute rather than staging constant wars over who controls the heavy weaponry of constitutional law from the past. If legislatures just passed rules and protected values majorities believe in, the distinction between “higher law” and everyday politics effectively disappears.

Hard to see what could go wrong! No Constitutional guarantees for freedom of speech, freedom of the press — heck, no Constitutional prohibition of slavery! Let whatever “values majorities believe in” reign! I mean, come on, when have majorities ever believed in unjust things?

What logicians used to call the “planted axiom” — the fundamental unstated assumption — is pretty obvious here: People who agree with me will always be in charge. So if there’s no freedom of the press, how is that a problem? We’ll just use our power to shut down Fox News, not any of the networks we approve of.

As I’ve been saying for many years, I am always fascinated by the number of philosophers who habitually consider political questions from the position of power. They never seem to imagine what the situation might look like if their enemies were the ones in charge.

taste and judgment

Re: Freddie’s post on the various ways you can like or dislike something, I wonder of this from Auden’s “commonplace book” A Certain World might help:

As readers, we remain in the nursery stage so long as we cannot distinguish between Taste and Judgment, so long, that is, as the only possible verdicts we can pass on a book are two: this I like; this I don’t like.

For an adult reader, the possible verdicts are five: I can see this is good and I like it; I can see this is good but I don’t like it; I can see this is good and, though at present I don’t like it, I believe that with perseverance I shall come to like it; I can see that this is trash but I like it; I can see that this is trash and I don’t like it.

I’m borderline-obsessed with these differently-angled straight lines.

revisiting Saul

After further reflection: I’m the mark. The easy mark. It pains me to say so, but I fell for it. Jimmy didn’t change — didn’t change at all; but he made me think he did. You got me, Jimmy. You’re good, man.

You have to play the cards you’re dealt, and Jimmy was dealt some very bad cards. But in the end, during that final courtroom scene, he played them beautifully — he worked a simultaneous double con.

Con one: To make the court — and ultimately the public, when the news is out — believe that he was the real mastermind behind the Heisenberg drug empire. Sure, he could’ve taken the seven years in cushy prison that he negotiated: but that would have meant being portrayed as a small-timer, a minor player in a game full of bigger players (Walt, Gus, Lalo). Not the deal he wants. So he trades in those seven years for a life sentence — but a life sentence in which he is forever known as the genius, the power behind the throne, the Big Player who had simply been disguised as, in the words of Betsy Kettleman, “the kind of lawyer guilty people hire” — and poor guilty people at that.

Con two: He makes absolutely certain that Kim is there, because at the same time that he is testifying to his own artistry and skill he also works to convince Kim that he has been moved by her example to become a brave truth-teller. (With the Sphinx-like Kim you can never be sure, but I’m inclined to think that she buys it. I don’t think she’d have visited him in prison otherwise.) Note that this idea — that Kim’s courage in making her affidavit stung his conscience and impelled him to reveal his real importance — also works for the public narrative: it makes his claim that he was the real mastermind feel like a confession rather than a boast.

Anyway: it’s fabulous! — the two parts moving in opposite directions, like a complex mechanism that opens one door even as it closes another. He cons the court and the public in one direction while conning Kim in the other. And life in prison is just the price he has to pay for executing that brilliant move. His satisfaction is in knowing that he is the absolute master of his chosen craft. That’s something he can meditate on for the next forty years or so. With or without ice cream.

Lambeth

Whither the Lambeth Conference 2022? I’ve been turning that question over and over in my mind, and I’ve finally realized what I think.

Imagine a married couple. The wife is dynamic, energetic, involved in the community and the pillar of the household too. The husband doesn’t do much, but he does love his weekly poker night with his friends. One afternoon he returns home after buying some beer for his poker buddies and discovers that his wife is gone. He has no idea where she is or when she might be coming back. But, you know, it’s poker night, so off he goes to Bill’s house.

That’s what I think Lambeth 2022 was. Poker night at Bill’s house, while one’s spouse is missing.

Kubrick the idealist

Diane Johnson, novelist and co-author with Stanley Kubrick of the screenplay of The Shining, writing just after the director's death:

Kubrick had a strong, offended sense of the ridiculousness of the human being, and the futility of human endeavor. He returned to these points again and again — with the recruit in Full Metal Jacket, everyone in Dr. Strangelove (the characters associated with Terry Southern), the victims in A Clockwork Orange. He assailed married life and artistic pretension in The Shining, which was also to have assailed racism (the Overlook Hotel had been built on an Indian burial ground), a theme that fell by the way. The new film may assail psychiatry, another subject he was skeptical of.

His pessimism seems to have arisen from his idealism, an outraged yearning for a better order, a wish to impose perfection on the chaotic materials of reality. This impulse is behind much art, after all, and Kubrick was above all an artist. His art was an expression of his view of things through the complicated medium of film. Like any artist, he felt an interest in controlling as many aspects of his medium as he could — set, music, costume, take — an attitude that unfairly earned him the reputation of monomaniacal difficulty.

But he thought of art as fun. Art in his view was also moral. People have tried to enlist him in the cause of hip nihilism, but this is to mistake his orthodox Sixties but rather conservative views. What was A Clockwork Orange — which he withdrew in England after some copycat killings — but a diatribe against violence? What were Dr. Strangelove and Full Metal Jacket but antiwar films?

It is very strange to me to hear the co-author of the the movie’s screenplay say that The Shining “assails” “married life” — a thought that has never occurred to me and still, despite her statement, refuses to occur to me. But in other respects I find this meditation interesting, because I have at least some sympathy for David Thomson’s view of Kubrick — in writing about The Shining, he says, “A masterpiece. How wonderful that this straining, chilly, pretentious, antihuman director should have stumbled into it.”

Thomson utterly despised 2001: writing in 2008 or thereabouts, he stated, as if giving testimony in court, “I believe now, as I did in 1968, that 2001 was a lavish travesty and an elaborate defense of vacancy or the reluctance to use real imagination. Of course, space can still work on film — we have had Alien, E.T., and others — but the lack of humanity is a dead end.” I think the “lack of humanity” is one of the chief points of that movie, and therefore it needed to be directed by someone whose style could fairly be described as “straining, chilly, pretentious, antihuman”; but Diane Johnson’s comments — along with those of people who knew Kubrick well — suggest that the apparent antihumanity is a mask for something deeper and more tender.

But it’s telling that if Kubrick did indeed have that more richly humanistic side — and I believe he did — he was never able to find a way to express it directly in his films. It’s something evoked by its absence, as when Shakespeare writes of “bare ruin’d choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.”

Incoming.

forgetting and propaganda

Jacques Ellul, Propaganda:

To the extent that propaganda is based on current news, it cannot permit time for thought or reflection. A man caught up in the news must remain on the surface of the event; he is carried along in the current, and can at no time take a respite to judge and appreciate; he can never stop to reflect. There is never any awareness — of himself, of his condition, of his society — for the man who lives by current events. Such a man never stops to investigate any one point, any more than he will tie together a series of news events. We already have mentioned man's inability to consider several facts or events simultaneously and to make a synthesis of them in order to face or to oppose them. One thought drives away another; old facts are chased by new ones. Under these conditions there can be no thought. And, in fact, modern man does not think about current problems; he feels them. He reacts, but he does not understand them any more than he takes responsibility for them. He is even less capable of spotting any inconsistency between successive facts; man's capacity to forget is unlimited. This is one of the most important and useful points for the propagandist, who can always be sure that a particular propaganda theme, statement, or event will be forgotten within few weeks. Moreover, there is a spontaneous defensive reaction in the individual against an excess of information and — to the extent that he clings (unconsciously) to the unity of his own person — against inconsistencies. The best defense here is to forget the preceding event. In so doing, man denies his own continuity; to the same extent that he lives on the surface of events and makes today's events his life by obliterating yesterday's news, he refuses to see the contradictions in his own life and condemns himself to a life of successive moments, discontinuous and fragmented.

This situation makes the “current-events man” a ready target for propaganda. Indeed, such a man is highly sensitive to the influence of present-day currents; lacking landmarks, he follows all currents. He is unstable because he runs after what happened today; he relates to the event, and therefore cannot resist any impulse coming from that event. Because he is immersed in current affairs, this man has a psychological weakness that puts him at the mercy of the propagandist.

Cf. my comment from a few years ago that “Silicon Valley serves the global capitalist order as its Ministry of Amnesia.”

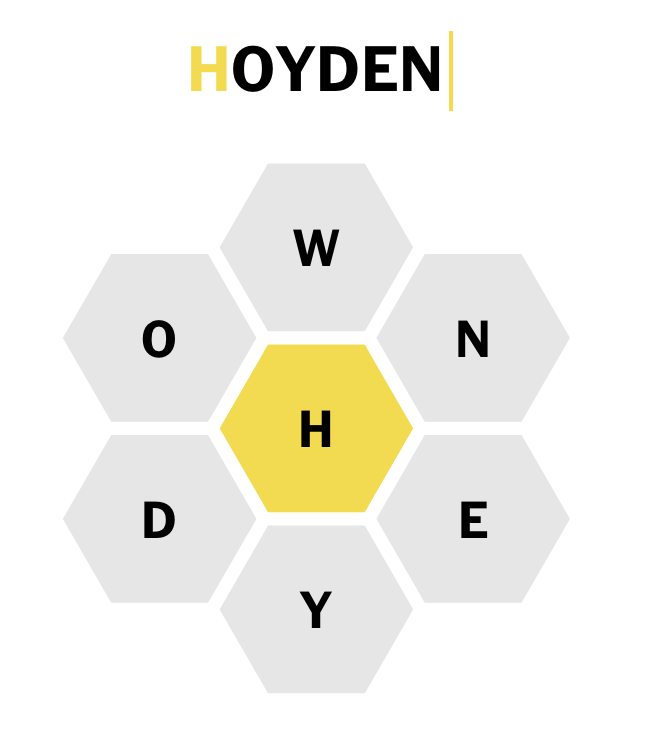

“Not in word list.” These people are barbarians.

liberalism vs. centrism, adjacency and action

I’ve written often about philosophical liberalism on this blog, because I have a complicated relationship to it. On the one hand, like John Milton, I don’t believe most of the things that philosophical liberals believe. On the other hand, it’s clear that at least some of the common critiques of liberalism fail to account for the complexity of the views of the smartest liberals, especially John Stuart Mill. Also, while the idea that liberalism provides a “level playing field” for all is and always has been a fiction, I believe that a more level playing field is something worth striving for, and that the current tendency among many Americans to make illiberal power grabs, or anyway to fantasize such power grabs, on the grounds that “politics ain’t beanbag,” is regrettable and makes me nostalgic for liberal proceduralism.

When people stop wanting a level playing field, they opt for a more confrontational model of politics — but there are several such models on offer, or perhaps it would be better to say that there are several kinds of confrontational practices, from the snarky to the murderous. In a new essay at the Hog Blog, I have tried to offer a taxonomy of those confrontational practices, and a suggestion that those of us who would like to see a lowering in our current level of toxicity should probably focus our attention on the people whose behavior is closest to our own. Adjacency as a guide to action.

Let me add to this gumbo one more idea — one that I should probably develop further at some point.

I often hear it said that people who reject illiberalism (of the right and the left, insofar as those terms have any meaning today) and who are committed to proceduralism are “centrists,” and while that might often be the case, it’s isn’t necessarily. I do not consider myself a centrist — indeed, my recent move towards anarchism (about which I’d like to say more, but I have to wait until my essay on the subject comes out) takes me considerably farther from the “center” of the current system than the Left Purity Cultists or the MAGA-heads, both of whom basically just want Management to take their side. There’s a simple distinction between ends and means at work here: the political ends I envision are pretty radical, but the means by which I hope to achieve them are peaceable and centered on persuasion, fair-mindedness, respect for the integrity of my political opponents, even charity. By contrast, the illiberals of left and right want to employ drastic means, but their ends would leave transnational capitalism securely in place. They’d just have managed to climb the greasy pole to the top; I’d like to take down the pole.

Bit of a scramble to get down to this part of the river, but it was worth it.

Evening coming on in the canyon