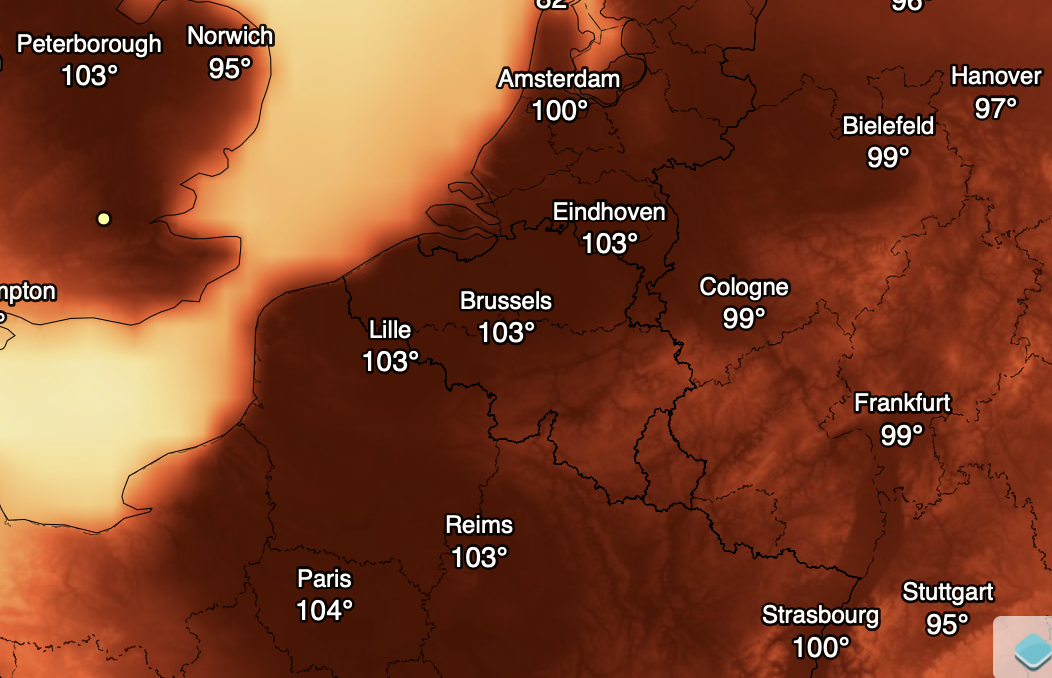

Being in London this week has been like having your home teleported somewhere else: You look around and everything is the same, but isn’t. The air is like Florida’s, hot and heavy to touch, the haze like a postcard of Los Angeles. My son went to school this morning in shorts, a vest, and a baseball cap that he turned backwards, as if he were actually in America. A mosquito buzzed in my ear as I sat in my darkened living room, the curtains drawn tight to keep the sun out. We don’t have air-conditioning in England, you see. That is the kind of thing people have in other countries, where the weather is extreme, where you go indoors to escape the heat—and where there are mosquitoes.

I just wrote an email to my friend Adam Roberts, who, like almost everyone in southern England and Western Europe, has been having a rough go of it:

Two years ago, when we had the Big Freeze here in Texas — three days without power, 35º F in most of the house, some warmth generated in one room only and by a rapidly diminishing supply of firewood (a friend eventually brought some over in his pickup) — the people responsible for the power generating stations said that their equipment wasn't prepared for that kind of cold, and why should it have been, it was a freakish thing, once in a lifetime, etc. To which more reasonable people replied that that excuse works only once at most. From now on, they said, given the swings of temperature that we'll surely be seeing, the Texas power grid will need to prepare for cold the way it prepares for heat.

It seems to me that the opposite may need to happen in northern Europe: an infrastructure preparing for heat the way it prepares for cold. And a mild-weathered place like Britain might need to invest in better preparation for both ends of the thermometer.

Fortunately, your nation and my state are blessed with exceptionally competent governments — they really know how to Level Up!!

what's done

Things without all remedy Should be without regard: what's done, is done.As regular visitors to this blog know, I recently read the four extant volumes of Robert Caro’s biography of Lyndon Johnson, and if there is a single message that Caro hammers relentlessly home it’s this: LBJ was a titanically horrible person – mean, vindictive, cruel, thieving – who nevertheless made vital things happen (electricity in the Texas Hill Country, massive national civil rights legislation) that would have been delayed a decade or longer if anyone else but him had been manipulating the levers of power. And then Caro leaves you, the reader, to decide whether you’re okay with the trade-off. Whether the good outweighs the bad.

Which brings us to the final season of Better Caul Saul, and particularly the ninth episode of the season, which explicitly calls into question our usual practices of double-entry moral bookkeeping.

Throughout the series, but especially in the last couple of seasons, we have seen the two sides of Kim Wexler: on one hand the woman who enjoys, with her lover and then husband Jimmy McGill (AKA Saul Goodman), con-artist “Fun and Games” – the bitterly ironic title of this episode – and on the other hand a dedicated public defender, a friend of the friendless, a skilled lawyer who even when she worked for a fancy law firm insisted on leaving plenty of time to do pro bono work for the insulted and the injured. Doesn’t the good outweigh the bad?

Season 6 episode 9 is the moment when Kim decides that the answer is No. Or rather: It’s the wrong question, the wrong system of accounting. She’s not willing to do the comparative weighing any more. She doesn’t know what she’ll do next, but she won’t do that.

Almost simultaneously, Mike Ehrmantraut visits the father of Nacho Varga, the young drug dealer and servant of the cartel who died in the third episode of this season. Mike wants to tell Mr. Varga that his son “had a good heart,” that he wasn’t like the other criminals, “not really.” Mike is surely thinking of his own son, whom he taught to be a crooked cop; and perhaps of himself also. But Mr. Varga isn’t having it. “You gangsters,” he says. “You’re all the same.” He won’t participate in double-entry accounting. And, along the same lines, he scorns Mike’s claim that “justice” will come to the Salamanca family at whose hands Nacho died. He knows that it’s mere vengeance.

“What’s done can be undone.” That’s what Jimmy/Saul says when Kim rejects the balancing act she’s been performing for almost the entire series. But the entire message of this fictional world — from Breaking Bad to Better Call Saul — is that it can’t be. Lady Macbeth knew: “What’s done cannot be undone.” Thus we’re all left to pick up the pieces, if we can. No system of accounting can rescue us from that dark obligation.

LOST, NOT STOLEN: The Conservative Case that Trump Lost and Biden Won the 2020 Presidential Election [PDF] — very well done, patiently detailed and thorough.

Is there a more user-hostile website on the internet than Patheos? I saw that my colleague Philip Jenkins had a new post and — momentarily forgetting what a bad idea this is — clicked the link rather than sending it straight to Instapaper. This is what I saw. Patheos thinks it a good idea to make the writing they publish impossible, and I mean impossible, to read without in some way bypassing the site itself. (The Mac/iOS Reader View usually works to achieve this, but occasionally gets confused by all the ads.) Even more than readers I feel sorry for the site’s writers, since many visitors will leave without discovering what those writers say.

Currently reading: Collected Poems by C. P. Cavafy 📚

Posted an update to my Buy Me a Dragon page.

Instagram’s transformation into QVC is now complete and absolute. Instagram is dead — or at least the Instagram I knew and loved is dead. It is no longer part of my photographic journey.

It’s way past time for anyone who actually cares about photos, and sharing photos, to ditch Instagram. Om himself has a photo blog, which is also how I’m using micro.blog. My friend Sara Hendren just told me about finite.photos, which looks promising. Glass isn’t, I think, quite right for me, but it’s lovely. Heck, there are even people still using Flickr, though my experience there was horrible. But anything is better than Instagram.

Sympathy for my northern European friends. (I could say “At least it won’t last long,” but they might reply, “At least you have A/C.")

improving

Education Doesn’t Work 2.0 - Freddie deBoer:

Entirely separate from the debate about genetic influences on academic performance, we cannot dismiss the summative reality of limited educational plasticity and its potentially immense social repercussions. What I’m here to argue today is not about a genetic influence on academic outcomes. I’m here to argue that regardless of the reasons why, most students stay in the same relative academic performance band throughout life, defying all manner of life changes and schooling and policy interventions. We need to work to provide an accounting of this fact, and we need to do so without falling into endorsing a naïve environmentalism that is demonstrably false. And people in education and politics, particularly those who insist education will save us, need to start acknowledging this simple reality. Without communal acceptance that there is such a thing as an individual’s natural level of ability, we cannot have sensible educational policy.Or: “Put more simply and sadly, nothing in education works.” By which he means: We haven’t yet found a system of education that reliably changes students’ success relative to other students. Young children who are the smartest in their cohort are almost certain to become adults who are the smartest in their cohort, and the same is true on down the line. Sobering, but, it seems, incontestable.

My own experience, for what little it’s worth, is that sometimes you get students who undergo dramatic changes in their academic performance, for good or for ill, but those changes have nothing to do with intelligence. Someone’s performance drops because of illness or emotional upheaval. Or, conversely: Many years ago I had a student who took several classes from me and never got anything better than a C. At the beginning of his senior year he came to my office and asked me why. I reminded him that I had always made detailed comments on his paper; he said, yeah, he knew that, but he had never read the comments and always just threw the papers away. So I explained what his problem was. He nodded, thanked me, went away, and in the two classes he had from me that year he got the highest grades in the class.

indestructible

This long post by Jesse Singal makes one key point perfectly clear: People on Twitter may know that 10,000 alarmist posts about their political enemies have been thoroughly debunked and discredited, but when that ten-thousand-and-first comes along they’ll instantly retweet it and add, “CAN YOU BELIEVE THIS CRAP???” And of course the lies will get a hundred times the exposure of the corrections. We all do well to remember Mark Twain’s “Advice to Youth”:

Think what tedious years of study, thought, practice, experience, went to the equipment of that peerless old master who was able to impose upon the whole world the lofty and sounding maxim that “Truth is mighty and will prevail” — the most majestic compound fracture of fact which any of woman born has yet achieved. For the history of our race, and each individual's experience, are sown thick with evidences that a truth is not hard to kill, and that a lie well told is immortal. There in Boston is a monument to the man who discovered anesthesia; many people are aware, in these latter days, that that man didn't discover it at all, but stole the discovery from another man. Is this truth mighty, and will it prevail? Ah, no, my hearers, the monument is made of hardy material, but the lie it tells will outlast it a million years. An awkward, feeble, leaky lie is a thing which you ought to make it your unceasing study to avoid; such a lie as that has no more real permanence than an average truth. Why, you might as well tell the truth at once and be done with it. A feeble, stupid, preposterous lie will not live two years — except it be a slander upon somebody. It is indestructible, then, of course, but that is no merit of yours.

My friend Chad Holley — lawyer, teacher, writer — describing a bold pedagogical decision:

If it was sage to leave well enough alone, I slipped up last month adding Solzhenitsyn’s lecture to the syllabus of a Law and Literature course I’m teaching at a local law school. Surely now I needed some intelligible comment on it, some ready defense. At least one faculty member, after all, had pushed back against the course on grounds of, well, frivolity. Fortunately, the dean who hired me had a delightfully simple view: the course would make students better people, and better people would make better lawyers. It carried the day, who am I to quibble? But for the Solzhenitsyn piece I was on my own. In the end I muttered to myself something about it offering an aesthetic that relates literature to morality, politics, and even the global order without succumbing to the instrumentalism of the savage. Eh. Close enough for adjunct work.

But did I say I added the piece to the syllabus? Friend, I began the course with it. We introduced ourselves, shared reasons for being here, covered some ground rules. Then I said, as distracted as I sounded, “Allll righty …so …” I had not anticipated just how much respect, how much admiration, I would feel for this small, diverse, self-selected group. They had read War and Peace “twice, but in Spanish,” their families had fled Armenia to escape Stalin, they were raising children, running businesses, staffing offices, nearly every one of them holding down a full-time day job while attending law school in the evenings, on the weekends. Had I really required these serious, ass-busting, tuition-remitting people to read an essay suggesting — I could barely bring myself to mouth it — beauty will save the world? What was I going to say for this in the face of their withering skepticism, their yawn of silence?

Read on to find out.

Didn’t think this guy was going to bloom this summer, but we returned from a few days away to find him going gangbusters.

Vast resources have been devoted over time to efforts to intervene in, ameliorate, and perhaps cure the mysterious conditions that constitute mental disorder. Yet, two centuries after the psychiatric profession first struggled to be born, the roots of most serious forms of mental disorder remain as enigmatic as ever. The wager that mental pathologies have their roots in biology was firmly ascendant in the late nineteenth century, but that consensus was increasingly challenged in the decades that followed. Then, a little less than a half century ago, the hegemony of psychodynamic psychiatry rapidly disintegrated, and biological reductionism once again became the ruling orthodoxy. But to date, neither neuroscience nor genetics have done much more than offer promissory notes for their claims, as I shall show in later chapters. The value of this currency owes more to faith and plausibility than to much by way of widely accepted science. […]

But the fundamental point remains: the limitations of the psychiatric enterprise to date rest in part on the depths of our ignorance about the etiology of mental disturbances.

Well hello

Small detail from Wildflowers (2017) by María Berrío

At The Modern in Forth Worth today, I was totally captivated by the mixed-media paintings of María Berrío.