And I’ve been saying for a long time now that we need to get out of this rut. You can shut things down for 15 days to slow the spread. You can even keep things semi-closed for a year until the arrival of vaccines. But you can’t just permanently impair the basic functioning of society due to a new respiratory virus; it doesn’t pass cost-benefit scrutiny. But that doesn’t mean there are no costs. We are living with lots of people dying of a virus that didn’t previously exist. We also have people going to the hospital and suffering long-term damage to their lungs or other organs. What the Covid hawks get right is that this is genuinely a very bad situation, and not just something we can declare ourselves “over.”

But the response we need is a pharmacological one, and that’s where we are failing.

The virus is evolving faster than our vaccines. And while scientists keep diligently plugging away at next-generation vaccination ideas, the idea of a whole-of-America effort to do R&D and production and fast-tracked regulatory approval seems gone and forgotten. That’s a disaster for the country, and we need to change course.

The whole post is very good, and unfortunately accurate in its diagnosis. See also this Eric Topol post. I’m not afraid, but I’m concerned.

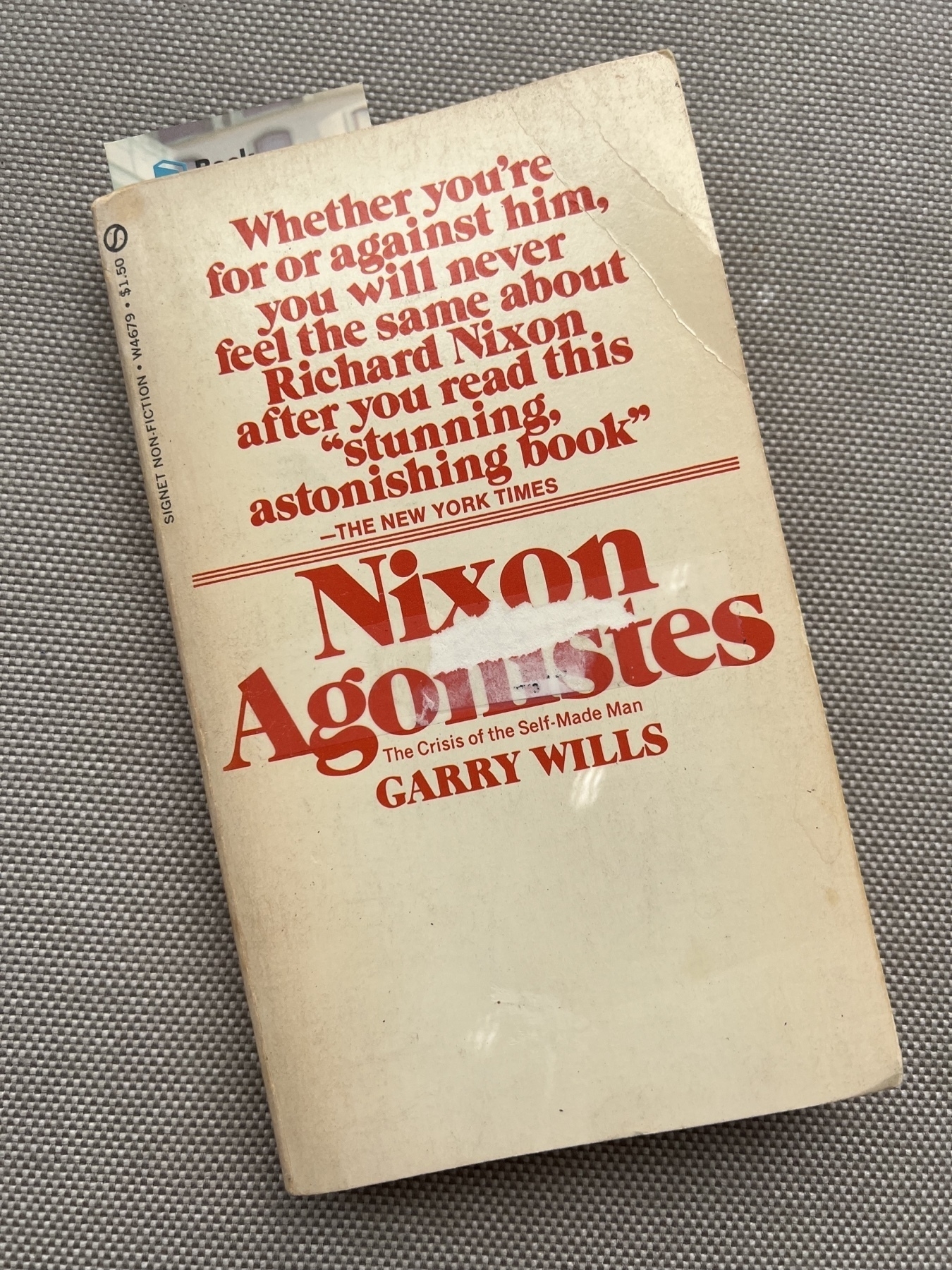

📚 Currently reading, in a copy I acquired in (I think) 1972:

A heartbreaking and powerful essay from Leah Libresco Sargeant:

A previous surgeon had told me to stop crying during a miscarriage, so this time my husband and I took a train ride to reach the hospital of a Catholic surgeon in New Jersey. We wanted a surgeon who took the loss of our child as seriously as the danger to my life.

The first person to see us was another ultrasound technician. Her voice got sharp when I asked if our baby had a heartbeat. “It’s not a baby, don’t talk like that,” she told me, as I lay on the table. Her voice softened a little, “You don’t have to think of it that way.” For her, part of providing care was denying there was any room for grief. […]

Doctors can’t value women more by dismissing our babies as worth less. Even women who support abortion access may find it jarring to have their child’s life dismissed when they hoped they would hold this baby. It’s better to be honest about tragedy and loss, than to pretend that only one person is on the table.

Caro's LBJ

After all these years, I am finally getting around to reading Robert Caro’s biography of Lyndon Johnson, and you know what? It is just as great as everyone says it is, maybe even greater. I’ve never read a better biography. What astonishes me is the skill with which Caro paces his story, considering its length, and considering how many digressions are necessarily embedded in it.

Caro is fabulously skilled at those digressions; he knows just how long they need to be in order to give the information that readers need if they are to grasp what LBJ was doing and why it mattered. In the first volume, his portrait of Sam Rayburn is a masterful mini-biography that tells us everything we need to know about that remarkable man in a dozen pages; it faithfully guides us when we see Rayburn’s actions later in the story. There are many such character sketches in this book, and each of them is a little marvel of lucidity, compression, and the art of the well-chosen detail. Thus we hear that W. Lee “Pappy” O’Daniel, the supposedly populist governor, when told that some people thought that his policies were betraying his supporters, plaintively replied, “How can they say I’m against the working man when I buried my daddy in overalls?”

But of these digressions, the best one in the first volume, surely, accompanies the account of how LBJ brought electricity to the farms and ranches of the Texas Hill Country. Caro gives us a brief but brilliant history of the daily lives of people of that region in the years before electricity: how they got their water; how they cooked and cleaned; how they milked their cows in the dark, not daring to bring a kerosene lantern into the barn for fear of fire. (Also: precisely how much light kerosene lanterns of the time provided.) He tells us why many of them were afraid of the coming of electricity, and afraid that the government would cheat them, as it had so often cheated them in the past. And then he tells us just how the electrical lines were built:

The poles that would carry the electrical lines had to be sunk in rock. Brown & Root’s mechanical hole-digger broke on the hard Hill Country rock. Every hole had to be dug mostly by hand. Eight or ten-man crews would pile into flatbed trucks – which also carried their lunch and water – in the morning and head out into the hills. Some trucks carried axemen, to hack paths through the cedar; others contained the hole-diggers. “The hole-diggers were the strongest men,” Babe Smith says. Every 300 or 400 feet, two would drop off and begin digging a hole by pounding the end of a crowbar into the limestone. After the hole reached a depth of six inches, half a stick of dynamite was exploded in it, to loosen the rock below, but that, too, had to be dug out by hand. “Swinging crowbars up and down – that’s hard labor,” Babe Smith says. “That’s back-breaking labor.” But the hole-diggers had incentive. For after the hole-digging teams came the pole-setters and “pikemen,” who, in teams of three, set the poles – thirty-five-foot pine poles from East Texas – into the rock, and then the “framers” who attached the insulators, and then the “stringers” who strung the wires, and at the end of the day the hole-diggers could see the result of their work stretching out behind them – poles towering above the cedars, silvery lines against the sapphire sky. And the homes the wires were heading toward were their own homes. “These workers – they were the men of the cooperative,” Smith says. Gratitude was a spur also. Often the crews didn’t have to eat the cold lunch they had brought. A woman would see men toiling toward her home to “bring the lights.” And when they arrived, they would find that a table had been set for them – with the best plates, and the very best food that the family could afford. Three hundred men – axemen, polemen, pikers, hole-diggers, framers – were out in the Edwards Plateau, linking it to the rest of America, linking it to the twentieth century, in fact, at the rate of about twelve miles per day.

All of this comes not from reading books – there’s much here that no book has told – but from interviewing people who were present when the electrification of the Hill Country happened. (In the late Seventies Caro and his wife, though lifelong and happy New Yorkers, moved for a couple of years to the Hill Country, because it took that long to acquire the older folks’ trust.)

Eventually, twelve miles a day, the electrification was done, though not without strain of many kinds. Here’s how the chapter concludes:

Brian Smith had persuaded many of his neighbors to sign up, and now, more than a year after they had paid their five dollars, and then more money to have their houses wired, his daughter Evelyn recalls that her neighbors decided they weren’t really going to get it. She recalls that “All their money was tied up in electric wiring” – and their anger was directed at her family. Dropping in to see a friend one day, she was told by the friend’s parents to leave: “You and your city ways. You can go home, and we don’t care to see you again.” They were all but ostracized by their neighbors. Even they themselves were beginning to doubt; it had been so long since the wiring was installed, Evelyn recalls, that they couldn’t remember whether the switches were in the ON or OFF position.

But then one evening in November, 1939, the Smiths were returning from Johnson City, where they had been attending a declamation contest, and as they neared their farmhouse, something was different.

“Oh my God,” her mother said. “The house is on fire!”

But as they got closer, they saw the light wasn’t fire. “No, Mama,” Evelyn said. “The lights are on.”

They were on all over the Hill Country. “And all over the Hill Country,” Stella Gliddon says, “people began to name their kids for Lyndon Johnson.”

Currently reading: The High Sierra: A Love Story by Kim Stanley Robinson 📚

The Amazon store experience, while presented as frictionless, contains a lot of friction—so much so that many people are excluded from entry. On top of the complex surveillance system, every customer needs to have a smartphone, have downloaded the Amazon app, logged in to an Amazon account, and connected a means of payment. When an Amazon Fresh store opened in West London in March 2021, a journalist observed an old man trying to go in to pick up some groceries, but he gave up when he was told all the steps he would have to take just to enter. “Oh f*** that, no, no, no — can’t be bothered,” he said, then kept walking to reach a normal grocery store. But in the future he may run into similar issues at even more stores, as countries like Sweden pioneer a cashless economy and the Amazon model inevitably spreads.

The extension of inequities, and even the creation of new ones, is a key part of the frictionless society that gets hidden by the digital services that claim to increase convenience and reduce barriers to consumption. Researcher Chris Gilliard coined the term “digital redlining” to describe the series of technologies, regulatory decisions, and investments that allow them to scale as actions that “enforce class boundaries and discriminate against specific groups.” In the same way that biases in artificial intelligence systems were long ignored, if not purposefully hidden, to protect companies' business interests, these frictionless tools also claim they will eliminate inequities, even as Gilliard argued that “the feedback loops of algorithmic systems will work to reinforce these often flawed and discriminatory assumptions. The presupposed problem of difference will become even more entrenched, the chasms between people will widen.”

The great thing about humility tweets is that you’re not trying to show that you are better than anybody else. You are showing that you are a regular, normal person, despite the fact that your life is so much more fabulous than those of the people around you. You are showing the world that you haven’t let your immense achievements go to your head! You’ve remained completely egalitarian — you just happen to be a better egalitarian than most people (and you are humbled by that fact). It’s easy to be humble when you’re most people. But just think about how amazing it is to be humble when you’re as impressive as you!

While plants do not demonstrate ESP or identify murderers, the fact that they are to some extent sentient, communicative, and social has been borne out by lots of recent scientific research far beyond what the polygraphers of Backster’s era might have imagined. At this point we know that plants can and do communicate among themselves and with other species: in forests, trees share information through underground mycelial networks, transmitting nutrients and news of climatic conditions through veins and roots and spores. It is through plant root structures that “the most solid part of the Earth is transformed into an enormous planetary brain,” according to Emanuele Coccia in The Life of Plants.

In an essay about nonhuman sociality, the anthropologist Anna Tsing says that plants do not have “faces, nor mouths to smile and speak; it is hard to confuse their communicative and representational practices with our own. Yet their world-making activities and their freedom to act are also clear — if we allow freedom and world-making to be more than intention and planning.” Tsing points out how bizarre it is that we have long assumed plants are not social beings — and that when we try to imagine them as such, it is through anthropomorphism: they are carnivorous murderers, or kindly creatures transmitting nature’s wisdom. Either way, the extent to which the plant is social depends on the extent to which the plant can socialize on our terms, with us. Who should speak for plants? Scientists? Filmmakers? Novelists?

Cf. this post.

If you could do it, I suppose, it would be a good idea to live your life in a straight line - starting, say, in the Dark Wood of Error, and proceeding by logical steps through Hell and Purgatory and into Heaven. Or you could take the King's Highway past the appropriately named dangers, toils, and snares, and finally cross the River of Death and enter the Celestial City. But that is not the way I have done it, so far. I am a pilgrim, but my pilgrimage has been wandering and unmarked. Often what has looked like a straight line to me has been a circling or a doubling back. I have been in the Dark Wood of Error any number of times. I have known something of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven, but not always in that order. The names of many snares and dangers have been made known to me, but I have seen them only in looking back. Often I have not known where I was going until I was already there. I have had my share of desires and goals, but my life has come to me or I have gone to it mainly by way of mistakes and surprises. Often I have received better than I deserved. Often my fairest hopes have rested on bad mistakes. I am an ignorant pilgrim, crossing a dark valley. And yet for a long time, looking back, I have been unable to shake off the feeling that I have been led — make of that what you will.

— Wendell Berry’s Jayber Crow

Digital natives are fit for their new environment but not for the old one. Coaches complain that teenagers are unable to hold a hockey stick or do pull-ups. Digital natives’ peripheral vision — required for safety in physical space — is deteriorating. With these deficits come advantages in the digital realm. The eye is adjusting to tunnel vision — a digital native can see on-screen details that a digital immigrant can’t see. When playing video games, digital immigrants still instinctively dodge bullets or blows, but digital natives do not. Their bodies don’t perceive an imaginary digital threat as a real one, which is only logical. Their sensorium has readjusted to ignore fake digital threats that simulate physical ones. No need for an instinctive fear of heights or trauma: in the digital world, even death can be overcome by re-spawning. Yet what will happen when millions of young people with poor grip strength, peripheral blindness, and no instinctive fear of collision start, say, driving cars? Will media evolution be there in time to replace drivers with autopilots in self-driving vehicles?

Currently reading: The Passage of Power (The Years of Lyndon Johnson, Vol. 4) by Robert A. Caro 📚

the sheepdog's view

I’ve been thinking about the weirdly intense hatred many conservatives feel for people like David French and Liz Cheney — for anyone they think isn’t “fighting.” Here’s my conclusion: The conservative movement has too many sheepdogs and not enough shepherds.

Sheepdogs do two things: they snap at members of the herd whom they believe to be straying from their proper place, and they bark viciously at wolves and other intruders. Sheepdogs are good at identifying potential predators and scaring them off with noisy aggression. (Often they suspect innocent passers-by of being wolves, but that just comes with the job description. Better to err on the side of caution, etc.)

What sheepdogs are useless at is caring for the sheep. They can't feed the sheep, or inspect them for injury or illness, or give them medicine. All they can do is bark when they see someone who might be a predator. And that's fine, except for this: the sheepdogs of the conservative movement think that everyone who is not a sheepdog – everyone who is not angrily barking — is a wolf. So they try to frighten away even the faithful shepherds. If they succeed, eventually the whole herd will die, from starvation or disease. And as that happens, the sheepdogs won't even notice. They will stand there with their backs to the dying herd and bark their fool heads off.

To give an honest accounting of ourselves, we must begin with our weakness and fragility. We cannot structure our politics or our society to serve a totally independent, autonomous person who never has and never will exist. Repeating that lie will leave us bereft: first, of sympathy from our friends when our physical weakness breaks the implicit promise that no one can keep, and second, of hope, when our moral weakness should lead us, like the prodigal, to rush back into the arms of the Father who remains faithful. Our present politics can only be challenged by an illiberalism that cherishes the weak and centers its policies on their needs and dignity.

annoyance

I like Independent Publisher, the WordPress theme you’re looking at, but I’m not crazy about it. I prefer Davis, the theme I was using before — but Davis just underwent an update that undid the custom CSS I was using to tweak it. Davis does something that many themes do, something indefensible and unforgivable: it renders all block quotes in italics. This is stupid, because sometimes such quotations contain italics of their own, which are wiped out by the CSS. Typically, it’s possible to use the Custom CSS feature in WordPress to fix things like that, and in the past I did that — but this new update has made the theme impervious to such changes. No matter what CSS I add, the theme ignores it. So I am back to Independent Publisher, which is … okay. Fine, I guess.

The whole situation is yet another reminder of how frustrating life in the indie web world can be if you don’t possess the tools you need to Do It Yourself. I really really don’t have the time to learn how to write my own WordPress theme … but that’s probably what I should do. Sigh.

Of course, another alternative would be to leave WordPress altogether for an alternative platform, but I suspect that will have to wait until I retire. Because that is a big job.

Today’s harvest

My iCloud issue: files I create on my iPhone take roughly 36 hours to show up on my Mac. This has been especially frustrating with photos, which I have to AirDrop to the Mac for editing. But getting out of the Apple ecosystem ain’t easy….