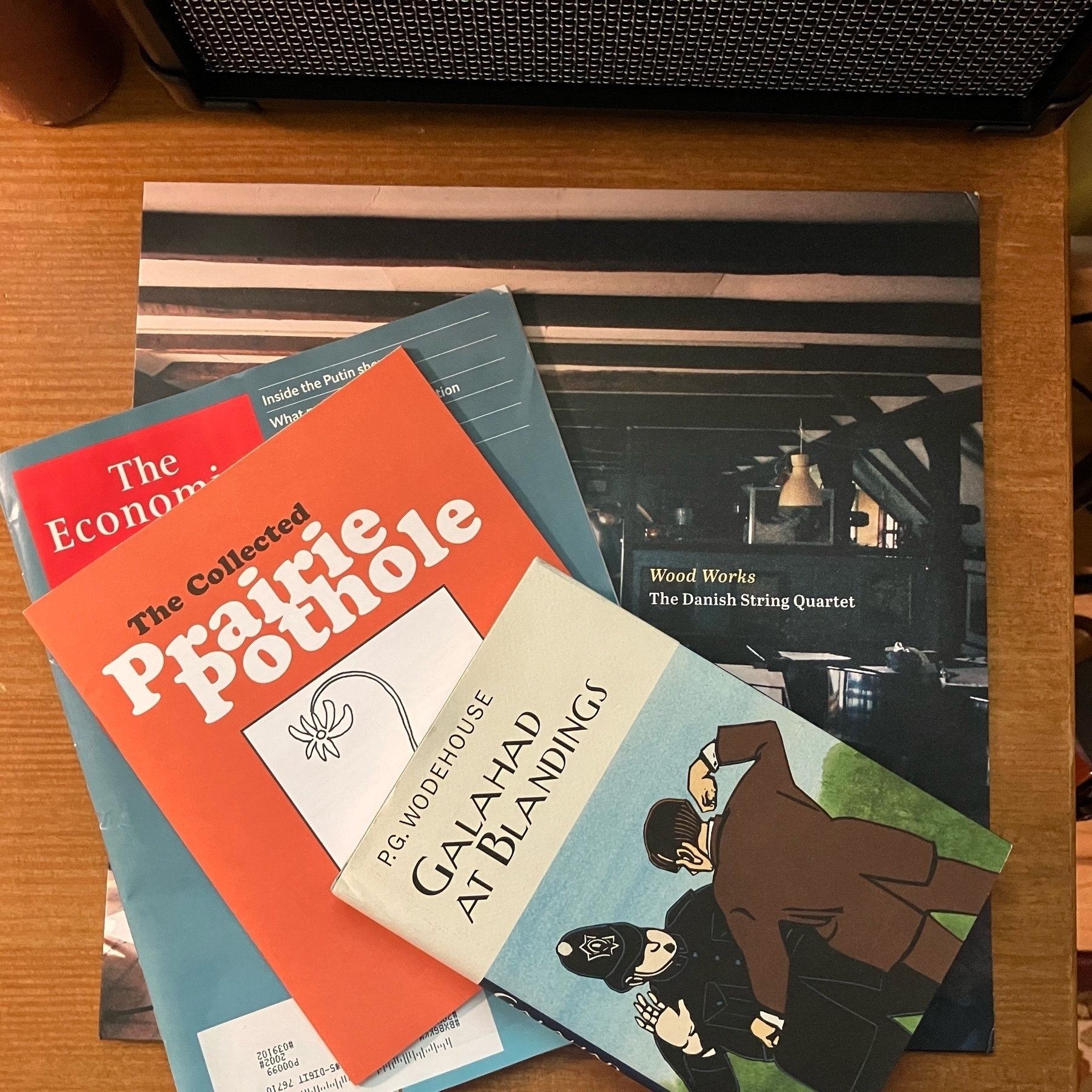

A festive harvest in the mail today. Listening to Wood Works right now and it’s utterly enchanting.

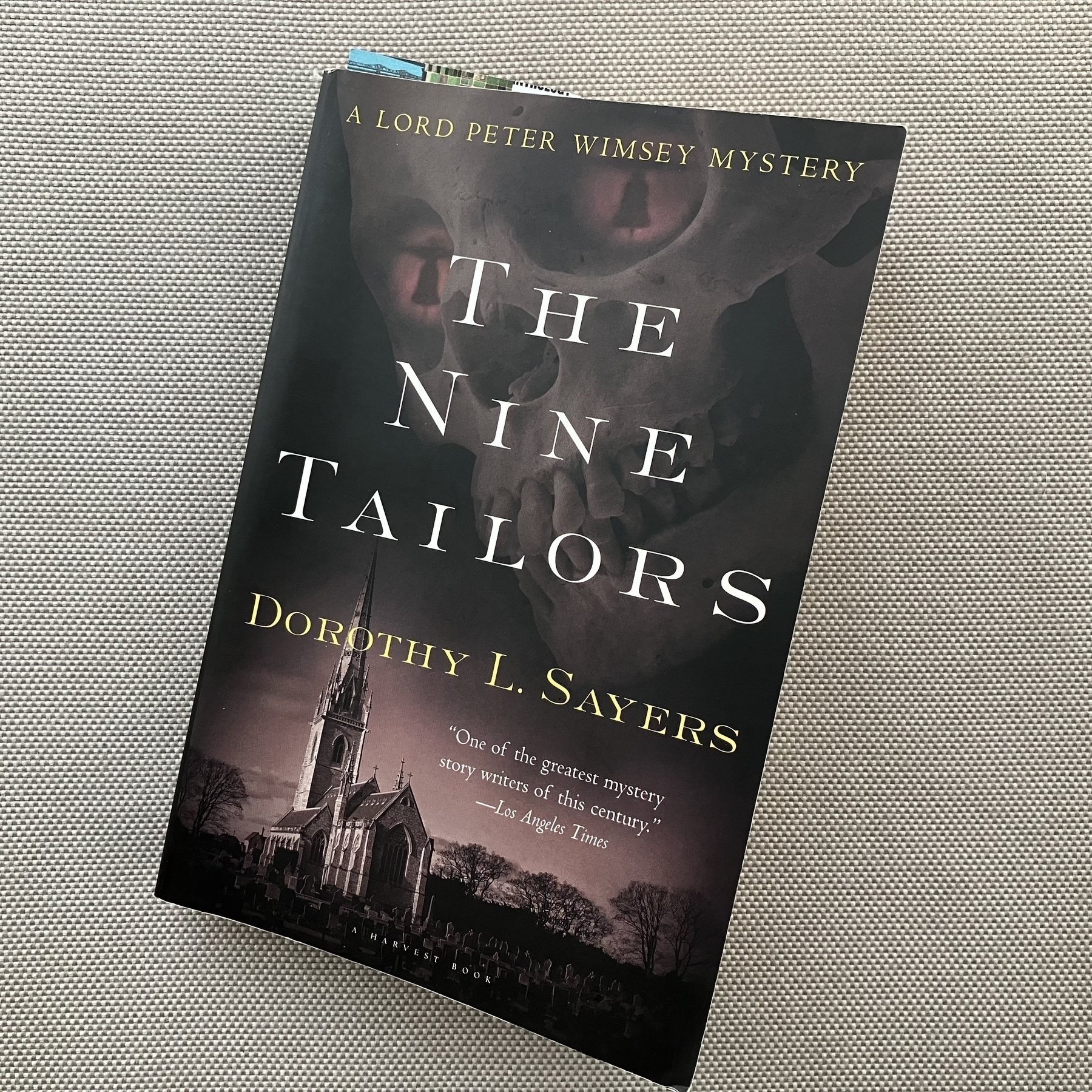

Currently reading: The Code of The Woosters by P G Wodehouse 📚 – I almost know this one by heart. In this difficult season of my life, Wodehouse’s stories have healing powers.

I have said that I think there is a strong case for the exclusion of the Moscow Patriarchate from the [World Council of Churches], and that they have a case to answer; I’m not suggesting that they should have no opportunity for such an answer. I don’t feel sanguine about their willingness to defend themselves in this particular “court”, but I would not advocate any precipitate decision without notice and consultation.

Should it come to this, however, my reasons for supporting an exclusion would be that we have a situation in which the hierarchy of one particular Christian organisation is actively advocating — not merely passively acquiescing in — a war of pure aggression, in which the routine slaughter of non-combatants is evidently a matter of accepted policy, and which is being presented by this hierarchy as a defence of Christian civilisation.

My question would be: If the behavior of the Moscow Patriarchate is insufficient to warrant an expulsion from the WCC, what would be sufficient? What kind of behavior, generally speaking, would lead to expulsion? My immediate feeling (subject to revision or correction) is that if this behavior isn’t bad enough to get you expelled, nothing is, and membership in the WCC is absolutely permanent.

Another dashed-off newsletter, though with some prime Wodehouse content.

The heat wave on the Indian subcontinent is making the terrifying opening chapter of Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future feel a good deal more prescient than KSR wants it to be.

when problems aren't trolley problems

A brief follow-up to my earlier post on effective altruism (EA): I have a feeling that what makes EA less effective than it aspires to be is its relentless presentism. EA always looks for strictly financial means to address a given problem and address it right now. But what if the interventions that make an immediate impact aren’t the ones that make the best long-term impact?

A decade ago Barbara H. Fried of Stanford Law School published an essay arguing that ethicists and legal scholars have a tendency to formulate all problems as trolley problems, in this sense:

The “duty not to harm” and conventional “duty of easy rescue” hypotheticals typically share the following three features: The consequences of the available choices are stipulated to be known with certainty ex ante; the agents are all individuals (as opposed to institutions); and the would-be victims (of the harm we impose by our actions or allow to occur by our inaction) are generally identifiable individuals in close proximity to the would-be actors). In addition, agents face a one-off decision about how to act. That is to say, readers are typically not invited to consider the consequences of scaling up the moral principle by which the immediate dilemma is resolved to a large number of (or large-number) cases.

I’m especially interested in the “one-off decision” business: What if interventions that are most effective in the short term are counter-productive in the long term? What if over the long haul attention to the cultivation of neighborliness is actually more effective? Something to consider.

There’s a good discussion of these matters in Matt Yglesias’s most recent newsletter.

my business

That said, I’m not sure that this is an issue we need to spend too much time on. The genuinely Christian view is, it seems to me, both longer and narrower. And maybe it’s not just Christians who need to think this way. I like to remind myself of this passage from Voltaire’s Candide:

In the neighborhood there was a very famous dervish who was considered the best philosopher in Turkey; they went to consult him; Pangloss was the spokesman and said to him: “Master, we have come to ask you to tell us why such a strange animal as man was ever created.”

“What are you meddling in?” said the dervish. “Is that your business?”

“But, Reverend Father,” said Candide, “there is a horrible amount of evil on earth.”

“What does it matter,” said the dervish, “whether there is evil or good? When his highness sends a ship to Egypt, is he bothered about whether the mice in the ship or comfortable or not?”

“Then what should we do?” said Pangloss.

“Hold your tongue,” said the dervish.

I'm pretty much with the dervish about this, but because as far as I can tell, Christ's call upon my life is essentially the same regardless of whether I think that current conditions are propitious or not. You people can keep debating these things if you want, but I have a couple of gardens to tend.

a story

In my first years at Wheaton College I had a colleague named Julius Scott. (He retired in 2000 and died in 2020. R.I.P.) Julius was a New Testament scholar, but earlier in life, in the 1960s, had been a Presbyterian pastor in Mississippi. He was raised in rural Georgia and loved the South, but he knew a good deal about our native region’s habitual sins also, and as the Civil Rights movement grew stronger and stronger, he understand that he had a reckoning to make. So he did.

After much prayer and study of Scripture, he decided that nothing could be more clear in Scripture, and nothing more foundational to Christian anthropology, than the belief that each and every human being is made in the image of God; that every human being is my neighbor; and that to “love your neighbor as yourself” is required of us all. Julius could not, therefore, avoid the conclusion that the Jim Crow laws common to the Southern states were incompatible with the Christian understanding of what human beings are and who our neighbors are; but even if those laws proved impossible to dislodge, and even if his pastoral colleagues thought them defensible, it was surely, certainly, indubitably necessary for all churches to welcome every one of God’s children who entered their doors, and to welcome them with open arms, making no distinction on the basis of race. When his presbytery — gathering of pastors in his region — next met, Julius felt that he had to speak up and say what he believed about these matters.

He did; and thus he entered into a lengthy season of hellish misery. He was prepared for the condemnation and shunning he received from almost every other member of the presbytery; what he wasn’t prepared for was what happened when word of his speech got out to the general public, I believe through a newspaper article: an ongoing barrage of threats against his life and the lives of his wife and children. For years, he told me, he had to sleep — and sleep came hard — with a loaded gun under his bed; the fear for his family didn’t wholly abate until he left Mississippi. (“I was afraid for my babies,” Julius said, and with those words the tears filled his eyes.) Of course he remained a pariah to most of his colleagues — and even the ones who respected him told him so in private, expressing their agreement with his theological conclusions only on condition that Julius never share their views with anyone else.

Think about that story for a while. Please understand that it’s not an uncommon one; and please understand, further, that Julius escaped with no worse than shunning and terror because he was white. (If you want to know more about Christians in Mississippi in that era, the persecuted and the persecutors alike, I recommend Charles Marsh’s book God’s Long Summer. And if you want to know what life in that era was like in Birmingham, Alabama, where I grew up, read Diane McWhorter’s Carry Me Home.)

Now: the next time you’re tempted to say that American Christians today experience hostility unprecedented in our nation’s history, and can escape condemnation only if they bow their knee to the dominant cultural norms; that it didn’t used to be like that, that decades ago no American Christian had to be hesitant about affirming the most elementary truths of the Christian faith — the next time you’re tempted to say all that, please, before you speak, remember Julius Scott.

Going around saying hello to the plants I wasn’t sure had made it through our cold snaps in the winter. (I mean, this is central Texas, so “winter.” But we had just a bit of genuine cold, and not all our plants made it through.)

Obviously, no one does this, I recognize this is a very niche endeavor, but the art and craft of maintaining a homepage, with some of your writing and a page that's about you and whatever else over time, of course always includes addition and deletion, just like a garden — you're snipping the dead blooms. I do this a lot. I'll see something really old on my site, and I go, “you know what, I don't like this anymore,” and I will delete it.

But that's care. Both adding things and deleting things. Basically the sense of looking at something and saying, “is this good? Is this right? Can I make it better? What does this need right now?” Those are all expressions of care. And I think both the relentless abandonment of stuff that doesn't have a billion users by tech companies, and the relentless accretion of garbage on the blockchain, I think they're both kind of the antithesis, honestly, of care.

Currently reading: David Copperfield by Charles Dickens 📚 – taking my own advice.

time

I want to connect a post of mine from five years ago —

There are always questions. Which ones arise — that’s not for us to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the questions that are presented to us. My one consistent position in all these matters is to resist taking the nuclear option of excommunication. It is the strongest censure we have, and therefore one not to be invoked except with the greatest reluctance. Further, I don’t think the patience that St. Paul commands is to be exhausted in a few years, or even a few decades. We need to learn to think in larger chunks of time, and to consider the worldwide, not just the local American and Western European, context. Many of us tend to think that, if we haven’t convinced someone after a few tweets and blog posts, we can be done with them and the questions they bring. But the time-frame of social media is not the time-frame of Christ’s Church.

— with a post of mine from ten days ago:

So it turns out that “the economic way of looking at life” – which is pretty much the American way of looking at life, and certainly the Silicon Valley way – means that you think of time as a scarce consumable resource. Which is indeed how most of us, it seems, think about time, and that, in turn, is why we might experience the idea of traveling at the speed of God as not just wrong but, more, offensive – a failure to maximize consumption.

Breaking that habit of thought, and imagining how to move at the speed of God – these are real and vital challenges. Maybe the first thing we need to learn how to repair is our disordered sense of time — time is not a scarce resource but rather a gift.

Increasingly I am convinced that we can’t make the changes we need to make — and I’m thinking not just of Christians, but also of all members of our current social order — until we reset our understanding and experience of time.

I even wonder whether the problem I posted about earlier today — what seems to me our increasing reluctance to pursue common rules for the social order, our disdain for proceduralism — is an outgrowth of a diseased experience of time. If we knew, if we really knew, that the people we despise are going to be our neighbors for the rest of our lives, then maybe we’d see the value in coming to some sort of procedural agreement with them before the shooting begins.

But then the shooting has already begun, hasn’t it?

points that don't need to be belabored

We know — we all know —

- That people impose standards on their Outgroup that they never impose on their Ingroup.

- That politicians do 180º turns on any and every issue, depending on which party controls Congress or the Presidency, or on what direction the Supreme Court seems to be leaning. (A quarter-century ago, when SCOTUS was left-dominated, the right complained about “the judicial usurpation of politics”; now that the composition of the court has changed, it’s the left making precisely the same complaint.)

- That people forgive politicians or actors or writers they approve of for sins that they vociferously condemn when committed by their cultural enemies.

- That people denounce “cancel culture” when someone they approve of is being hounded but call precisely the same behavior “accountability culture” when they’re hounding someone they hate.

- That the most inconsistent people in earth will furiously denounce their political enemies for inconsistency.

We know all that now, we don’t need to keep pointing it out. We also know that pointing it out won’t change anyone’s behavior. So what’s next? What’s the next step, socially and politically, if a common standard for all is no longer on the table?

Ross Douthat is a brilliant writer and an old friend, but I wish he wouldn’t participate — as he does in this essay — in the fiction that intra-Catholic disputes constitute the whole of Christian thought.

Puppets by Paul Klee named the Philistine, Matchbox Spirit, and the Crowned Poet — Source: Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The coming food catastrophe | The Economist:

By invading ukraine, Vladimir Putin will destroy the lives of people far from the battlefield — and on a scale even he may regret. The war is battering a global food system weakened by covid-19, climate change and an energy shock. Ukraine’s exports of grain and oilseeds have mostly stopped and Russia’s are threatened. Together, the two countries supply 12% of traded calories. Wheat prices, up 53% since the start of the year, jumped a further 6% on May 16th, after India said it would suspend exports because of an alarming heatwave.

The widely accepted idea of a cost-of-living crisis does not begin to capture the gravity of what may lie ahead. António Guterres, the un secretary general, warned on May 18th that the coming months threaten “the spectre of a global food shortage” that could last for years. The high cost of staple foods has already raised the number of people who cannot be sure of getting enough to eat by 440m, to 1.6bn. Nearly 250m are on the brink of famine. If, as is likely, the war drags on and supplies from Russia and Ukraine are limited, hundreds of millions more people could fall into poverty. Political unrest will spread, children will be stunted and people will starve.

Mr Putin must not use food as a weapon. Shortages are not the inevitable outcome of war. World leaders should see hunger as a global problem urgently requiring a global solution.

It’s hard to imagine anything more important for the world’s governments to focus on. I doubt that they will; I pray that they will.