Persillade in process.

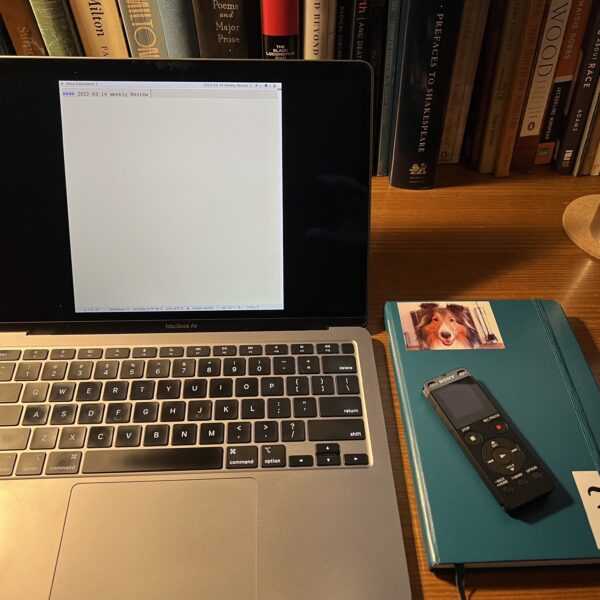

The Monday morning ritual: reviewing whatever inchoate ideas emerged during the past week and putting the useful ones in a text file. Sometimes I write by hand, sometimes I dictate thoughts, sometimes I type them. My so-much-missed dog Malcolm is on the cover of my notebook because I want to be like him: calm, sweet, and always a pleasure to be around. (He was also beautiful, but I don’t aspire to that.)

[caption id="" align=“aligncenter” width=“1280”] Lwów, Poland, 1938[/caption]

Lwów, Poland, 1938[/caption]

aspiring to realism

Adopting a realistic approach towards the world does not consist in always reaching for a well-worn toolkit of timeless verities, nor does it consist in affecting a hard-boiled attitude so as to inoculate oneself forever against liberal enthusiasm. Realism, taken seriously, entails a never-ending cognitive and emotional challenge. It involves a minute-by-minute struggle to understand a complex and constantly evolving world, in which we are ourselves immersed, a world that we can, to a degree, influence and change, but which constantly challenges our categories and the definitions of our interests. And in that struggle for realism – the never-ending task of sensibly defining interests and pursuing them as best we can – to resort to war, by any side, should be acknowledged for what it is. It should not be normalised as the logical and obvious reaction to given circumstances, but recognised as a radical and perilous act, fraught with moral consequences. Any thinker or politician too callous or shallow to face that stark reality, should be judged accordingly.I very much like this idea of Realpolitik not as a position but rather, properly understood, an aspiration. Often what people call their “realism” is simply their intellectual and moral laziness.

Perhaps related: I’ve always been slightly annoyed by the tagline of the New Criterion — “The New Criterion will always call things by their real names” — because it assumes that knowing the real names of things is easy. A better and more honest, if less resonant, tagline would be “We will always call things by their real names if we can figure out what they are.”

[caption id="" align=“aligncenter” width=“720”] Neil Young (1967) by Jini Dellaccio. See a lovely brief film about her work here.[/caption]

Neil Young (1967) by Jini Dellaccio. See a lovely brief film about her work here.[/caption]

[caption id="" align=“aligncenter” width=“700”] Imiri Sakabashira[/caption]

Imiri Sakabashira[/caption]

civil heart, disinterested charity

Well, it was very odd what Mr. Sammler found himself doing as he lay in his room, in an old building. Settling, the building had cracked its plaster, and along these slanted cracks he had mentally inscribed certain propositions. According to one of these he, personally, stood apart from all developments. From a sense of deference, from age, from good manners, he sometimes affirmed himself to be out of it, hors d'usage, not a man of the times. No force of nature, nothing paradoxical or demonic, he had no drive for smashing through the masks of appearances. Not "Me and the Universe." No, his personal idea was one of the human being conditioned by other human beings, and knowing that present arrangements were not, sub specie aeternitatis, the truth, but that one should be satisfied with such truth as one could get by approximation. Trying to live with a civil heart. With disinterested charity. With a sense of the mystic potency of humankind. With an inclination to believe in archetypes of goodness. A desire for virtue was no accident.New worlds? Fresh beginnings? Not such a simple matter. (Sammler, reaching for diversion.) What did Captain Nemo do in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea? He sat in the submarine, the Nautilus, and on the ocean floor he played Bach and Handel on the organ. Good stuff, but old. And what of Wells' Time Traveler, when he found himself thousands of years in the future? He fell in square love with a beautiful Eloi maiden. To take with one, whether down into the depths or out into space and time, something dear, and to preserve it – that seemed to be the impulse. Jules Verne was quite right to have Handel on the ocean floor, not Wagner, though in Verne’s day Wagner was avant-garde among the symbolists, fusing word and sound. According to Nietzsche the Germans, insufferably oppressed by being German, used Wagner like hashish. To Mr. Sammler’s ears, Wagner was background music for a pogrom. And what should one have on the moon, electronic compositions? Mr. Sammler would advise against that. Art groveling before Science.

— Saul Bellow, Mr. Sammler's Planet

"We know the next planet outside of our solar system is at least 5,000 years away," [Werner Herzog] tells Ars. "It's very hard to do that, and [whatever is there is] probably uninhabitable. And we know that on Mars, there's permanent radiation that will force us underground in little bunkers. We know that we have no breathing or water [on the surface], and Elon Musk once suggested exploding nuclear bombs at the poles to melt the ice and then, of course, with gigantic systems of pipelines, bring it somewhere to a city."— Ars Technica. My favorite meme would be a little video of Werner Herzog saying “Good luck with that.”He pauses. “Good luck with that,” he says.

sounds

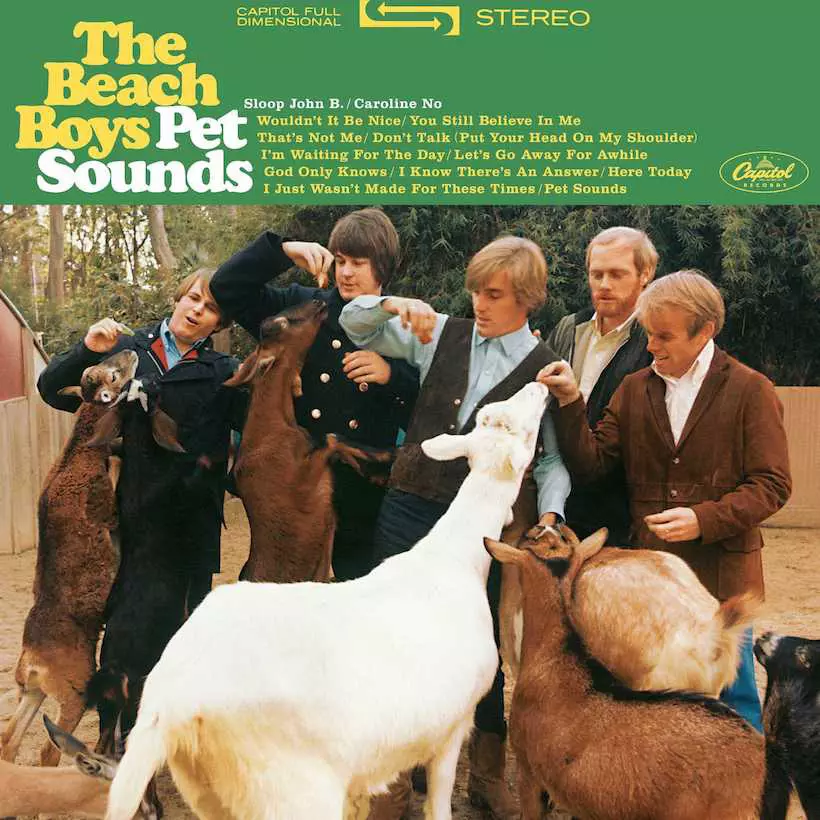

[caption id="" align=“aligncenter” width=“820”] “The worst cover in the history of the record business” – Bruce Johnston[/caption]

“The worst cover in the history of the record business” – Bruce Johnston[/caption]

Pet Sounds was recorded in 27 sessions spread over four months and using four different studios, each of which was selected for its distinctive sound, created through a combination of the physical design of each studio and the unique consoles and tape machines available. Wilson recorded the instrumental backing track first, usually in one session, using the best freelance session musicians then working in Hollywood. This use of session musicians instead of band or Beach Boys members, and the wide range of instrumentalists used, including bass harmonica and the theremin, was almost unheard of in rock at this time. Wilson would work with musicians individually, singing or playing them the details of their part and experimenting with them to create the sound he wanted. He would then experiment with the whole band, instructing them on their relative positions to their mikes, altering echo effects, which he recorded live, and further experimenting with details of rhythm and combinations of sounds before recording a take. He would then record several takes until he was completely happy with every detail of the backing track.A fascinating article about both Brian Wilson’s recording process and the ways that his musical innovations confused both The Beach Boys’ audience and their record company. (Though the record was a big success in Britain, for reasons Butler explains.) Someone — alas, I can’t remember who — once commented that the big difference between The Beach Boys and the Beatles in that era is that the Beatles were able to innovate without alienating, or even lessening the enthusiasm of, their audience. There are many potential reasons for this divergence, but surely one of them is that the Beatles’ transformation was gradual while the one overseen by Brian Wilson was pretty sudden. But make no mistake: Pet Sounds is as good as any record the Beatles ever made.This method of experimenting in the studio and working with the musicians to help realise the sounds that he had imagined was unique at the time; a combination of mixing live and composing on the spot. He recorded the backing tracks on three- or four-track tape machines, depending on which studio he was in. […]

Capitol executives were not pleased with the finished album. The sales department in particular were worried because the production, style and subject matter were so different from the established image of the Beach Boys, with their wholesome, ‘fun in the sun’ image. The album was nevertheless released in America on May 16th, 1966. Unfortunately, despite some glowing reviews amongst American music critics, it was, by the Beach Boys’ standards, a relative flop, peaking briefly at number ten on the album chart on 2nd July, and was the first Beach Boys record in three years not to go gold.

I’ve been listening to Pet Sounds a lot lately, and I’ve been listening to it on vinyl. That’s an experience that even a year ago I would have said was not going to happen. Just before we moved to Waco in 2013, I took my vinyl collection — which had been sitting in boxes in my basement; I hadn’t had a turntable in at least twenty years — to Half Price Books and sold the lot. “Wow, you’ve got some cool records here,” the clerk commented. “You sure you want to sell these?” I winced, but reminded myself that, as just noted, I hadn’t listened to any of them since Ronald Reagan was President — and said, with a sigh, Yeah, I’m sure. And that was the end of vinyl records for me.

Or so I thought. What happened? Well, gifts happened – over the years a handful of LPs, which I couldn’t listen to. And then one day I did a casual search for turntables, and realized that you can get a decent one for not much money … it took me a while to pull the trigger, but looking back I can see that it was inevitable.

My good friend Rob Miner has a massive collection of LPs, but sometimes reminds me that he’s not a “vinyl fundamentalist.” And he’s not – but plenty of people are. And I have always been annoyed by the language of such fundamentalists: they talk about “warmth” and “presence” and “depth” – What the hell is that all about? Such metaphors have zero meaning to me. I scornfully dismissed all such talk … until I started listening to music on my new turntable.

The first record that really caught my attention is this beautiful remaster of a 1959 recording of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons featuring Felix Ayo as soloist. I had previously heard it in a lossless digital format; but vinyl was a totally different experience. The next thing that knocked me out was Boards of Canada’s The Campfire Headphase, which in recent weeks I have listened to over and over and over again. Also: Tinariwen, Emmaar – a fabulous record. And then came Pet Sounds; and now, I fear, there’s no going back. I listen to these LPs and think: Such warmth! Such depth! Such presence!

Yeah, I’m gonna have to work on my metaphors. I really have no idea how to describe my experience. All I know is that when I listen to the records named above, and a few others, I listen to the entire album, I listen with undistracted attention, and I listen over and over. I rarely do any of those things with my digital collection; I don’t do it often even with my CDs. The sound of these vinyl records compels me. (I bought a cheap old copy of The Band’s magnificent second album, only to discover that it’s crackly as hell throughout – and I even like that. It’s a fit for the style of that particular masterpiece. I am becoming a cliché. I am becoming that guy.)

Not everything benefits from the viny treatment; maybe not many things do. I wouldn’t listen to Arvo Pärt’s music on anything but CD; ditto with Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks. I am attached to certain jazz recordings on CD – Miles Davis, Theolonius Monk – and am somewhat afraid to find out what they sound like on vinyl … but they sound so great on CD that I’m not really tempted. (Yet?) And a lot of the ambient music I listen to seems made for the limitlessness of digital streaming. But what does benefit from vinyl benefits tremendously.

I had this post drafted when the great Ted Gioia announced that he has recently rediscovered vinyl. That’s when I knew I had done the right thing.

Harmonized Region (1938), Paul Klee; Art Institute of Chicago

Source: UW-Milwaukee Special Collections

What a lovely tribute to Willie Nelson’s sister Bobbie, the heartbeat of his band for so many years. R.I.P.

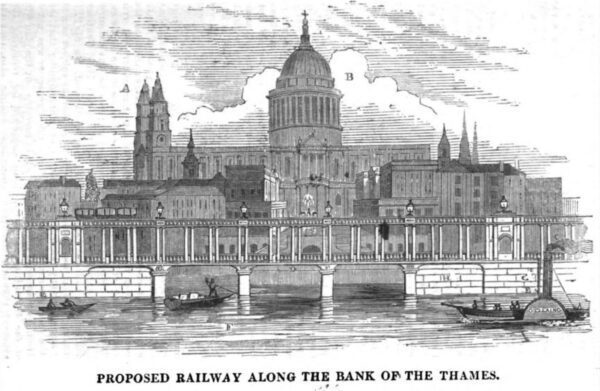

The Embankment Railway never happened -- thank God.

consecration to culture

Culture is the child of each individual’s self-knowledge and dissatisfaction with himself. Anyone who believes in culture is thereby saying: ‘I see above me something higher and more human than I am; let everyone help me to attain it, as I will help everyone who knows and suffers as I do: so that at last the man may appear who feels himself perfect and boundless in knowledge and love, perception and power, and who in his completeness is at one with nature, the judge and evaluator of things.’ It is hard to create in anyone this condition of intrepid self-knowledge because it is impossible to teach love; for it is love alone that can bestow on the soul, not only a clear, discriminating and self-contemptuous view of itself, but also the desire to look beyond itself and to seek with all its might for a higher self as yet still concealed from it. Thus only he who has attached his heart to some great man receives thereby the first consecration to culture.

— Nietzsche, from “Schopenhauer as Educator”

a useful distinction

An ‘epistemic bubble’ is an informational network from which relevant voices have been excluded by omission. That omission might be purposeful: we might be selectively avoiding contact with contrary views because, say, they make us uncomfortable. As social scientists tell us, we like to engage in selective exposure, seeking out information that confirms our own worldview. But that omission can also be entirely inadvertent. Even if we’re not actively trying to avoid disagreement, our Facebook friends tend to share our views and interests. When we take networks built for social reasons and start using them as our information feeds, we tend to miss out on contrary views and run into exaggerated degrees of agreement.

An ‘echo chamber’ is a social structure from which other relevant voices have been actively discredited. Where an epistemic bubble merely omits contrary views, an echo chamber brings its members to actively distrust outsiders. In their book Echo Chamber: Rush Limbaugh and the Conservative Media Establishment (2010), Kathleen Hall Jamieson and Frank Cappella offer a groundbreaking analysis of the phenomenon. For them, an echo chamber is something like a cult. A cult isolates its members by actively alienating them from any outside sources. Those outside are actively labelled as malignant and untrustworthy. A cult member’s trust is narrowed, aimed with laser-like focus on certain insider voices. In epistemic bubbles, other voices are not heard; in echo chambers, other voices are actively undermined.

How to Discover the Life-Affirming Comforts of ‘Death Cleaning’:

Professional home organizers are reporting a spike in calls from older customers asking for help sorting through their belongings, seeking to dole out the heirlooms and sentimental items and toss the excess. The mood, organizers say, is largely upbeat, with people eager to part with china, furniture and photographs. In some cases, the inquiries come from grown children on behalf of their aging parents, keen to get ahead on the task so they don’t have to do it alone later.

“There’s been a shift in the consciousness of people 70 and over,” said Ann Lightfoot, a founder of Done & Done Home, a New York City home-organizing company that saw its business double in 2021, and an author of the forthcoming book, “Love Your Home Again.” “They’re like, ‘Oh my God, nobody wants my stuff. I don’t even want my stuff.’”

Professionals often refer to the task as “death cleaning,” a term popularized in 2018 with the publication of the book, “The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning,” by Margareta Magnusson, which posited that the prospect of our eventual demise is reason enough to purge.

I hadn’t seen this when I wrote my post on keeping my books, but I kinda think that books are different. Books aren’t just stuff. Books have a distinctive ability to hold personal but transferable meaning.

Various journalists complained that I described MBS as personally “charming” and “intelligent.” To this my reply is twofold. First, MBS was indeed charming and intelligent, and if you want me to say otherwise, then you want to be lied to. Second, if you think charm and intelligence are incompatible with being a sociopath, then your years in Washington, D.C., have taught you less than nothing.

Any publication bragging that it is too sanctimonious to accept an invitation to interview the crown prince of Saudi Arabia is admitting it cannot cover Saudi Arabia. The Atlantic is not in the business of sanctimony, and it expects its readers to understand, without being told, that someone who dwells on his own indignities as the result of a murder, rather than on the suffering of the victim, might not be the perfect steward of absolute power.

Three points in response:

- This is precisely correct.

- Wood’s profile of MBS is absolutely brilliant.

- The complaints about it are yet further evidence of Twitter’s ability to transform intelligent people into complete idiots.