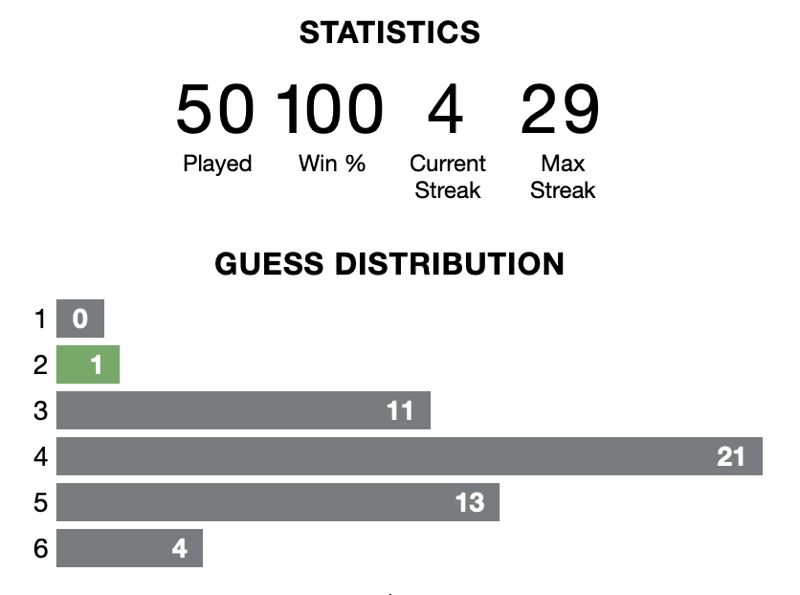

Took me this long to get it in two. Will I ever get it in one? Doubtful.

The risks of netwar and cyberwar are consequences of convenience. Communications networks became widespread, delivering previously unthinkable quantities of bespoke content instantly. As they ballooned and megascaled, they offered more opportunities for exploitation that might affect larger populations much more rapidly. Meanwhile, business and government operations elected to take on new vulnerabilities in their computer infrastructure in order to win operational conveniences. Those conveniences once seemed worth it. Not anymore.

Maybe – but when have we ever been willing to give up on our conveniences, no matter how dangerous?

On my first visit to Moscow, I met one of Lenin’s embalmers. “When I began, the body was in a poor state”, said Styopa, whose expertise was the use of electricity. Skin grafts and a new partial-vacuum glass sarcophagus had helped to inhibit decay, but Styopa’s shock treatment had reversed it. “Once every two or three months, a high-voltage charge was applied to keep up the tone. But the first time we tried it I overestimated the power needed. Lenin suddenly sat up from the table, his arms shook, and his lips started to quiver. I thought he was going to speak. It was quite a shock. After that, we reduced the voltage.”

doing your own research

In 2016, director Dean Fleischer-Camp — known for his work on the viral hit, Marcel The Shell With Shoes On — released Fraud, a “meta-documentary” composed of a series of home videos. They follow a family with a mounting pile of debts participating in a crime spree to wipe the slate clean. Though the videos that make up the film are real, the story itself is entirely fabricated: Fleischer-Camp made the film after stumbling onto an account holding hundreds of hours of home videos. By methodically going through this vast archive, he was able to recombine these clips into a crime narrative. Suddenly, a clip of a woman spraying her carpet becomes a woman about to burn down a home.

In a Q&A following Fraud’s premiere at Toronto’s Hot Docs festival, Fleischer-Camp was called a “con artist” and “liar” by audience members who were disturbed by his working methods. These viewers took issue not with the film’s plot, but its construction. Unlike Loose Change, which purports to discover the truth in a lie, Fraud explicitly attempts the reverse, showing that one could convincingly tell any story with materials found on a site like YouTube. Ironically, it’s Fraud that, to its critics, defies the open, truth-leaning and “collaborative” ethos that people associate with the platform.

Fleischer-Camp’s unforgivable sin is showing people who pride themselves on “doing their own research” that they don’t have the first idea what research is or how to do it, and that, as a direct consequence, they are easy marks for crooks who know how to play to their intellectual self-assessment. As Kim says in his concluding paragraph:

YouTube is a space where the successors of Burroughs, Gysin, and Bachman meet, where author and viewer at least appear to collapse, and the possibilities of the webpage open up. The ability to engage as a viewer has never been so substantive. But this sense of engagement is double-edged: it can allow for new innovations in narrative, but also in persuasion and propaganda. The feeling of engagement is not the same thing as actually engaging. “Do your own research” is less an imperative than a strategy of flattering one’s audience: the implication is that you have done your own research simply by watching the film. Despite controlling the playback, the user is just as passive as ever.

Injured Parties

I have an essay in the new Hedgehog Review — behind a paywall, but shouldn't you subscribe? Yes indeed you should. The essay is called "Injured Parties," and it begins thus:

In 1923, the American movie star Dorothy Davenport lost her husband, the actor and director Wallace Reid, to an early death resulting from complications of morphine addiction. After the tragedy, Davenport took up the job — an unusual one for a woman in Hollywood in that era — of film producer. Starting with Human Wreckage, a movie about the dangers of drug addiction that appeared just months after Reid’s death, Mrs. Wallace Reid, as she now called herself, oversaw a series of films on pressing social issues. For instance, the third one she produced, and which she personally introduced in a prologue, The Red Kimono (1925), portrays the dark personal and social consequences of prostitution.

All of Davenport’s moral-crusading films were popular, but also controversial: Some were banned by the British Board of Film Censors and by the guardians of public morals in many American cities. The Red Kimono had other problems, though, problems related to one Gabrielle Darley. Darley was a young woman who in the second decade of the twentieth century had worked as a prostitute in Arizona for a pimp named Leonard Tropp. She fell in love with him and they moved to Los Angeles, where she gave him money to buy a wedding ring — for herself, she thought, but in fact Tropp planned to marry another woman. When Darley discovered this, she shot Tropp dead. In 1918, she was put on trial for murder, but had the great good fortune of being represented by an exceptionally eloquent defense attorney named Earl Rogers — a close friend of William Randolph Hearst — who presented her as having been, before meeting Tropp, “as pure as the snow atop Mount Wilson.” The jury couldn’t get enough of this kind of thing and enthusiastically acquitted Darley.

One of the journalists covering the trial was Rogers’s daughter, Adela Rogers St. Johns, who was already well on her way to earning her unofficial title as “World’s Greatest Girl Reporter.” (For many years she worked for Hearst newspapers, and may have reached the height of her fame in her reporting on the 1935 trial of Bruno Richard Hauptmann for kidnapping and murdering the young son of Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh.) She wrote a short story, based on the trial, called “The Red Kimono.” It caught the attention of Dorothy Davenport, who immediately commissioned a screenplay and started filming. The name she chose for the film’s protagonist? Gabrielle Darley.

I describe Darley’s claim to having been defamed by the film — to being injured reputationally — and the ultimate decision of the Supreme Court of California in her favor.

From there I go on to explore the meaning of defamation and how it has changed over time, with a particular focus on the early modern period, during which, as I learned from reading that wonderful scholar Debora Shuger, defamation was very differently understood. I indulge my suspicion that we — immured in a social-media environment for which defamation is more or less the coin of the realm — might have a few things to learn from that era, and also from Erving Goffman. Yeah, I know it sounds weird, but trust me, it all holds together. I think. Ultimately I am trying to imagine charity as both a legal and a social concept. The point of the essay is not to settle any current issues but rather, by looking into the past, to discover alternative and superior moral vocabularies with which to address our disagreements.

Subscribe and read, please!

Half the point I want to make is that I have had a charmed life. I was whisked out of the way of the Nazis, bundled out of the way of the Japanese army, and, after a safe and happy four years in India, found myself in England instead of returning to Czechoslovakia in good time to grow up under communism. But I haven't made my point even yet. I wasn't merely safe, I was in the land of tolerance, fair play and autonomous liberty, of habeas corpus, of the mother of parliaments, of freedom of speech, worship and assembly, of the English language. I didn't make this list when I was eight, but by 18 I would have added the best and freest newspapers, forged in the crucible of modern liberty, and the best theatre. When I was 19 there occurred the Hungarian revolution, and my first interest was in how the story was being covered. On my 23rd birthday I panicked because I'd written nothing except journalism, and wrote a derivative play. When I was 31, Russian tanks rolled into Prague, and my wife got angry with me because I was acting English and not Czech. She was right. I didn't feel Czech. I had no memory of Czechoslovakia. I condemned the invasion from the viewpoint of everything I had inherited at the age of eight, including my name. During all that time, I had never been without a bed, or clothes to put on, or food on the table, or without medicine when I was sick, or a school desk to sit at. As I grew up I never had to put on a uniform except as a boy scout. As a journalist and writer I had never been censored or told what to write. As a citizen I never had to fear the knock at the door. The second half of the point I want to make is that if politics is not about giving everybody a life as charmed as mine, it's not about anything much.

Big Bend National Park, taken a while back.

The mothership … um, I mean the newsletter has landed.

Antonio Stradivari, the ‘Davidoff’ cello (1712)

songs you're entitled to sing

Edwin Muir was born and raised in the Orkneys at the end of the 19th century, and in his Autobiography (1954) recalls the songs he and his family sang — some of which were old ballads in Scottish English; but a few, in standard English and featuring references to such exotic locales as Paddington Green, had somehow been acquired from books and magazines:

There was a great difference between the earlier and the later songs. The ballads about James V and Sir James the Rose had probably been handed down orally for hundreds of years; they were consequently sure of themselves and were sung with your full voice, as if you had always been entitled to sing them; but the later ones were chanted in a sort of literary way, in honour of the print in which they had originally come, every syllable of the English text carefully pronounced, as if it were an exercise. These old songs, rooted for so long in the life of the people, are now almost dead.

I wonder what it would be like to sings songs “as if you had always been entitled to sing them” — entitled because they were the songs of your people, your world — and songs neither bought nor sold but rather inherited and passed along.

(When my late father-in-law was a child in Columbiana, Alabama, his family was very poor, and could afford no musical instruments; so evening after evening, they just sat on the front porch and sang in four-part harmony. All of them experienced music in a way I never have and never will. Eventually they did a little better, financially, and Daddy C — as I would call him, decades later — got a cheap guitar from Sears as a Christmas present. But he had no one to teach him to play until a friend of his sister’s, a fellow his own age but from Montgomery, came by one day and taught him a few chords. That friend was named Hank Williams — and yep, it was that Hank Williams.)

I think often of something Muir wrote, in his diary, about himself:

I was born before the Industrial Revolution, and am now about two hundred years old. But I have skipped about a hundred and fifty of them. I was really born in 1737, and till I was fourteen no time-accidents happened to me. Then in 1751 I set out from Orkney for Glasgow. When I arrived I found that it was not 1751, but 1901, and that a hundred and fifty years had been burned up in my two days' journey. But I myself was still in 1751, and remained there for a long time. All my life since I have been trying to overhaul that invisible leeway.

He grew up in a world technologically and socially little different than that of his distant ancestors: the family had a few books and a couple of fiddles, but their culture was largely shared and maintained by voice. Can anyone today born into the Western world say the same? Some, perhaps; but few.

A book I admire tremendously is Iona and Peter Opie’s The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren, and in her Introduction to a recent edition of the book Marina Warner raises an inevitable question:

How perennial is the lore and language that the Opies chronicled? Much of the material is ancient, reported in the first printed records of children's sayings and doings, with echoes reverberating much further back; certain themes and attitudes, certain rhythms and prosody, especially the humor and the daring, are eternal and inextinguishable. The Opies themselves invoke the bugbear of the mass media, which was already, even in the 1950s, accused of extinguishing children's spontaneity in play and expressiveness. The sociologist David Holbrook, in his book Children's Games [1957], lamented the disappearance of traditional play, citing as causes “recent developments in television, in the mass-production of toys, in family life, and the tone of our ways of living,” but for their own time at least the Opies confidently refuted this.

Could they “confidently refute” such a lament today? While Warner insists that “children haven’t forgotten how to play,” she also says this: “We are in danger of cultural illiteracy, of losing the past. If nestlings are deprived of their parents' song during a certain ‘window’ at the beginning, they will not learn to sing. This sounds uncomfortably recognizable.”

Children will always play, when allowed to, and people will always sing. But will they play or sing anything that can’t be bought and sold? Will playing and singing, in the Western world anyway, ever again be anything other than a set of commercial transactions? I’m glad that I can listen to almost any music in the world that I want to listen to; but I can’t help wondering sometimes whether music would mean something more to me, and certainly something different, if most of the songs I knew were the ones that, in that imagined life, I’d be entitled to sing.

Adam Roberts, “Ozymandias Replies”:

So, friend, you think my face and legs in stone Are signs that I have failed? Friend, think again. When I ascended to my marble throne The land was forest, meadow, lakeside glen. I took it and I wasted it. This desert tract Stands as my most expansive monument: Dead-life, as blank as hope, as bald as fact. I made a world of sand. And it’s this spent Stage-set, bleached clean, that I am proudest of — More than my palaces and bling and war — Because it’s the perfection of my love When my rule’s push came to my people’s shove. We tyrants know what power’s really for. I made my desolation to endure.

Rebecca Newberger Goldstein, from Plato at the Googleplex: Why Philosophy Won't Go Away:

Socrates was probably the first to identify aretē with what is — in terms of a person’s moral makeup or moral character — analogous to the health in that person’s body. A person doesn’t have to be recognized as healthy in order to be healthy, and so it is with Plato’s Socrates’ aretē. In the myth of the Ring of Gyges, presented in the Republic, Plato argues that even if a person could get away with all manner of wrongdoing while maintaining a good reputation because of a magic ring that renders him invisible, still he should not do any of these awful things, since by destroying his aretē the man will destroy himself. Aretē then is entirely independent of social regard. And in the Gorgias, Socrates is presented as asserting something so radical that his hearers think it has to be a joke. He would, he says, rather be treated unjustly than treat others unjustly (469c). But if aretē is conceived of as analogous to the health of the body, then Socrates’ statement is hardly absurd. The injustice that we do involves us far more intimately than the injustice that we suffer.

When the skylight in your bathroom enables photo-as-abstract-art …