runs

In footy (aka soccer) it is possible for players to make the following kinds of run:

- Mazy

- Marauding

- Lung-bursting

- Darting

- Slaloming

The Laws of the Game permit these runs and no others.

albeit

WIRED: Why do you call the metaverse dystopian?

John Hanke: It takes us away from what fundamentally makes us happy as human beings. We’re biologically evolved to be present in our bodies and to be out in the world. The tech world that we’ve been living in, as exacerbated by Covid, is not healthy. We’ve picked up bad habits — kids spending all day playing Roblox or whatever. And we’re extrapolating that, saying, “Hey, this is great. Let’s do this times 10.” That scares the daylights out of me.

Whereas you want people to actually experience daylight, albeit with a phone in their hands.

I really got into this idea of using digital tech to reinvigorate the idea of a public square, to bring people off the couch and out into an environment they can enjoy. There’s a lot of research that supports the positive psychological impact of walking through a park, walking through a forest — just walking. But now we live in a world where we have all this anxiety, amplified by Covid. There’s a lot of unhappiness. There’s a lot of anger. Some of it comes from not doing what our bodies want us to do — to be active and mobile. In our early experiments, we got a lot of feedback from people who were kind of couch potatoes that the game was causing them to walk more. They were saying, “Wow, this is amazing, I feel so much better. I’m physically better, but mentally I’m way more better. I broke out of my depression or met new people in the community.” We said, “Wow, like, this is good we can do in the world.”

How about not having the phone in your hands. Hanke says, "AR is the place where the real metaverse is going to happen.” How about it not happening at all.

covid in four states

| STATE | Cases/100k | Deaths/100k |

|---|---|---|

| California | 18,260 | 198 |

| Texas | 19,466 | 268 |

| Florida | 23,995 | 295 |

| New York | 23,423 | 318 |

Data from the NYT. I chose the four most populous states, in large part because they represent very different ways of dealing with Covid. Choose the state you’re interested in at the top of the linked page.

Remember how I said that there are some trees around here that think it’s still autumn? (Photo taken half an hour ago.)

defenseless

Juliette Kayyem, who among other things is a security consultant:

But what if the essence of a place is that it is defenseless? What if its ability to welcome others, to be hospitable to strangers, is its identity? What if vulnerability is its unstated mission? That is the challenge I hadn’t considered….

In security, we view vulnerabilities as inherently bad. We solve the problem with layered defenses: more locks, more surveillance. Deprive strangers of access to your temple, I urged the committee members [at Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh], and have congregants carry ID. They would have none of it. Access was a vulnerability embedded in the institution, and no security expert could change that — we do logistics, not souls.

The standoff in Colleyville ended with the attacker dead and the hostages unharmed. But all around the country, synagogues are no doubt convening their security committees, wondering what more they can do to defend their members without losing their essential vulnerability. A synagogue is not like an airport or a stadium. When it becomes a fortress, something immeasurable is lost.

drawing a narcissus

Ruskin’s instructions to his students:

Suppose you have to paint the Narcissus of the Alps. First, you must outline its six petals, its central cup, and its bulbed stalk, accurately, in the position you desire. Then you must paint the cup of the yellow which is its yellow, and the stalk of the green which is its green, and the white petals of creamy white, not milky white. Lastly, you must modify these colours so as to make the cup look hollow and the petals bent; but, whatever shade you add must never destroy the impression, which is the first a child would receive from the flower, of its being a yellow, white and green thing, with scarcely any shade in it. And I wish you for some time to aim exclusively at getting the power of seeing every object as a coloured space. Thus for instance, I am sitting, as I write, opposite the fireplace of the old room which I have written much in, and in which, as it chances, after this is finished, I shall write no more. Its worn paper is pale green; the chimney-piece is of white marble; the poker is gray; the grate black; the footstool beside the fender of a deep green. A chair stands in front of it, of brown mahogany, and above that is Turner’s Lake of Geneva, mostly blue. Now these pale green, deep green, white, black, gray, brown and blue spaces, are all just as distinct as the pattern on an inlaid Florentine table. I want you to see everything first so, and represent it so. The shading is quite a subsequent and secondary business. If you never shaded at all, but could outline perfectly, and paint things of their real colours, you would be able to convey a great deal of precious knowledge to any one looking at your drawing; but, with false outline and colour, the finest shading is of no use.

Newsletter: on fakery and Hittites.

Currently reading: Andrey Tarkovsky: Life and Work: Film by Film, Stills, Polaroids & Writings 📚

the whys and wherefores of humanistic study

Reading Weinstein and Montás, you might conclude that English professors, having spent their entire lives reading and discussing works of literature, must be the wisest and most humane people on earth. Take my word for it, we are not. We are not better or worse than anyone else. I have read and taught hundreds of books, including most of the books in the Columbia Core. I teach a great-books course now. I like my job, and I think I understand many things that are important to me much better than I did when I was seventeen. But I don’t think I’m a better person.Sure, but have you tried to be?

I don’t want to be too flippant here. I have myself, many times, argued against the claim that reading great books is intrinsically ennobling. My argument has been that how we read — with whom, and with what purposes in mind — matters more than what we read. But I think it’s both possible and desirable for students and teachers to read and study together in search of wisdom. And that’s largely what Montás and Weinstein argue for. I do think they are a rather too reverent about the books officially designated as Great, rather too confident in the value of mere exposure to such books. Still, the purposes of education, of teaching and learning, are their chief theme.

They also — Menand complains about this at length — say that in the modern university the practices of reading associated with those true purposes of education are either marginalized or forbidden. Menand actually quotes Montás’s argument that “Too often professional practitioners of liberal education — professors and college administrators — have corrupted their activity by subordinating the fundamental goals of education to specialized academic pursuits that only have meaning within their own institutional and career aspirations.” But isn’t it pretty obvious that someone who thinks this will not, indeed cannot, also think “that English professors, having spent their entire lives reading and discussing works of literature, must be the wisest and most humane people on earth”?

Menand is so transparently impatient with the arguments of Montás and Weinstein that he gets similarly confused at several points in his essay. For instance, to Montás’s claim that Nietzsche is “Satan’s most acute theologian,” Menand replied that “Nietzsche wanted to free people to embrace life, not to send them to Hell. He didn’t believe in Hell. Or theology” — or, presumably, Satan. But maybe Montás believes in Satan, which would, surely, be the point.

Let’s try to focus on the key issue here: Both authors under review couldn’t be clearer that their main argument is not that we should all be reading great books but that we should be reading great books in light of what they believe to be “the fundamental goals of education.” So the proper question to ask is not, “Will reading great literature make me a better person?” The proper question is, “Will reading great literature in company with others who are in search of self-knowledge, meaning, and wisdom make me a better person?” (Answer: Maybe not. And not automatically. But it does give you certain opportunities for becoming wiser if in a disciplined way you choose to take them.)

Why does Menand teach in a university? I read his essay three times looking for evidence, and the only thing I find is this: “The university is a secular institution, and scientific research — more broadly, the production of new knowledge — is what it was designed for.” (He sets this in opposition to the argument of the writers he review that it’s vital to read for self-knowledge.) He says that “Humanists … should not be fighting a war against science. They should be defending their role in the knowledge business.”

With this point I’m in complete agreement. Wissenschaft should not be simply dismissed in favor of Bildung, and there can be real Wissenschaft in the humanities (though I’m not sure many of the critics and theorists Menand defends are interested in either educational tradition). I agree with Tom Stoppard’s A. E. Housman, in The Invention of Love:

A scholar's business is to add to what is known. That is all. But it is capable of giving the very greatest satisfaction, because knowledge is good. It does not have to look good or even sound good or even do good. It is good just by being knowledge. And the only thing that makes it knowledge is that it is true. You can't have too much of it and there is no little too little to be worth having. There is truth and falsehood in a comma.Among my own writing and works, the ones I am proudest of are the ones — like my Auden editions — in which I am clearly if in a small way adding to our store of knowledge.

So two cheers, at least, for Wissenschaft. The chief point I’m wanting to make here is simply this: There’s something rather peculiar about a scholar who proudly disavows using professional teaching and study for personal moral formation and then says, as though he’s clinching a point, that his professional teaching and study have not contributed to his personal moral formation.

Okay, time to get this second career started.

The Homebound Symphony

Much of Emily St. John Mandel’s novel Station Eleven — set largely in Michigan some twenty years after a global pandemic kills 99% of humanity — focuses on the experiences of the Traveling Symphony, led by a man named Dieter:

The Symphony performed music — classical, jazz, orchestral arrangements of pre-collapse pop songs — and Shakespeare. They’d performed more modern plays sometimes in the first few years, but what was startling, what no one would have anticipated, was that audiences seemed to prefer Shakespeare to their other theatrical offerings.

“People want what was best about the world,” Dieter said.

Later we learn that “All three caravans of the Traveling Symphony are labeled as such, THE TRAVELING SYMPHONY lettered in white on both sides, but the lead caravan carries an additional line of text: Because survival is insufficient.” Dieter says, “That quote on the lead caravan would be way more profound if we hadn’t lifted it from Star Trek,” but not everyone agrees that the quote’s origin is a problem. Take wisdom where you find it, is their view.

In his dyspeptic screed of fifty years ago, In Bluebeard’s Castle, George Steiner talks about living in a “post-culture” — a society whose culture has died even if its monuments may remain:

At great pains and cost, Altstädtte, whole cities, have been rebuilt, stone by numbered stone, geranium pot by geranium pot. Photographically there is no way of telling; the patina on the gables is even richer than before. But there is something unmistakably amiss. Go to Dresden or Warsaw, stand in one of the exquisitely recomposed squares in Verona, and you will feel it. The perfection of renewal has a lacquered depth. As if the light at the cornices had not been restored, as if the air were inappropriate and carried still an edge of fire. There is nothing mystical to this impression; it is almost painfully literal. It may be that the coherence of an ancient thing is harmonic with time, that the perspective of a street, of a roof line, that have lived their natural being can be replicated but not re-created (even where it is, ideally, indistinguishable from the original, reproduction is not the vital form). Handsome as it is, the Old City of Warsaw is a stage set; walking through it, the living create no active resonance. It is the image of those precisely restored house fronts, of those managed lights and shadows which I keep in mind when trying to discriminate between what is irretrievable — though it may still be about — and what has in it the pressure of life.

A powerful passage; but, while I agree with Steiner that we are living in a kind of post-culture, I reject his language of the “irretrievable,” or as he says elsewhere in that essay, “irreparable.” I’ll explain why.

First the bad news. I don’t know a statement more indicative of the character of our moment than this by J. D. Vance: “I think our people hate the right people.” It’s what almost everyone believes these days, isn’t it? That they and their people hate the right people. And it seems to me that that is a pretty good definition of a post-culture: a society in which people have no higher ambition than to bring down those they perceive to be their enemies. (I’m setting aside the obvious point that Christians aren’t supposed to hate anyone.) I couldn’t agree more with my friend Yuval Levin that our moment is A Time to Build, but when you’re only concerned with hating the right people, who has time to build anything?

There are a lot of people out there doing good work to expose the absurdities, the hypocrisies, and the sheer destructiveness of both the Left and the Right. I myself did some of that work for several years, but I'm not inclined to keep doing it, largely because that work of critique, however necessary, lacks a constructive dimension. There has to be something better we can do than curse our enemies — or the darkness of the present moment. If I agree with Yuval that this is indeed a time to build, then what can I build?

And as regular readers of this blog know, my particular emphasis is not on building from scratch but on restoring, renewing, and repairing. As Steiner notes, the remnants of Culture Lost surround us -- still more so than when he wrote those words: the great benefit of the Internet is its ability to preserve cultural artifacts that very few people have any use for today. But such preservation is not automatic and inevitable. On the Internet, things get lost, links stop working, even the Wayback Machine is not able to rescue everything, though it rescues a hell of a lot. My task, as I now conceive it, is not to engage in critique but rather to bear a small light and keep it burning for the next generation and maybe the generation after that. I want to find what is wise and good and beautiful and true and pass along to my readers as much of it as I can, in a form that will be accessible and comprehensible to them.

That last point is worth emphasizing. Great works of art and of wisdom cannot always speak clearly for themselves: they often need an interpreter. And sometimes they need to be revised to some degree to make them useful to us. This is why I have talked about vendoring culture: the creative activity of making accessible and vivid what otherwise could be inscrutable and might therefore seem pointless. It is a teacherly thing to do, I suppose, and that makes sense for me, because I have never been able to think of myself primarily as a scholar or a writer but rather as a teacher who writes. Wordsworth famously wrote “what we have loved, others will love, and we will teach them how” – but if we don't teach them how, then there is very little chance that they will indeed love what we have loved.

Station Eleven had the Traveling Symphony: I'm trying to be the Homebound Symphony. Just one person sitting in my study with a computer on my lap, reading and listening and viewing, and recording and sifting and transmitting – sharing the good, the true, and the beautiful, with added commentary. The initial purpose of this work is to repair, not the whole culture, but just my own attention. On a daily basis I retrain my mind to attend to what is worthy. It is the task of a lifetime, especially in an environment which strives constantly to commandeer my attention, to remove it from my control, to make me a passive consumer of what others wish me to look at or listen to.

So first of all I'm doing this work — this blog; my essays; my books; my newsletter, which is all about praise and delight — for myself, but one of the reasons that I can be disciplined in redirecting my attention is that I’ve learned that if I do so it can be helpful to others. That's really been the great lesson for me of the last few weeks — since I started my Buy Me a Coffee page: I've learned that a few people appreciate the ways in which I can help them redirect their own attention.

As David Samuels has said in a memorable essay, “My problem is how to escape from it all in order to continue being me. The aim of any sane person in an age like this one is to be free to love the people you love and secure the freedom of [your] own thoughts, the same way you step out of the way of an oncoming truck.” But it’s not only about continuing to be myself, or even about loving my family and friends (though that love will always be my first priority). Survival is insufficient. I also feel an obligation to cup my hand around a candle to shield its flame in the strong winds. As the book of Proverbs teaches us, “The spirit of man” — including the manifestations of that spirit in art and music and story — “is the candle of the Lord.” My job is to keep that candle burning and pass it along to those who come after me. I don’t think anything that we’ve lost or neglected is irretrievable or irreparable, not even if I fail in my duty. I think often about what Tom Stoppard’s Alexander Herzen says near the end of The Coast of Utopia: “The idea will not perish. What we let fall will be picked up by those behind. I can hear their childish voices on the hill.”

Can't stop? Won't stop.

It's not just Wordle, the App Store is a total mess | Macworld:

It’s would be a trivially small amount of money for Apple to create an internal group dedicated to proactively finding and eliminating scam, copycat, infringing, exploitive apps. But every one it finds costs Apple money. And doing nothing isn’t hurting sales, not when it’s so much cheaper to just market the App Store as so secure and trustworthy. Apple seems to view App Store trust and quality as a marketing activity more than a real technical or service problem.

Jason Cross is absolutely correct. Whenever you hear one of our tech megacompanies say “Our platform is simply too big — we can’t effectively fight abuse” (of whatever kind), what they mean is “Our platform is simply too big — we can’t effectively fight abuse without reducing our profit margins.”

Currently reading: The Complete Works of W. H. Auden: Poems, Volume II: 1940–1973 by W. H. Auden 📚

Currently reading: The Complete Works of W. H. Auden: Poems, Volume I: 1927–1939 by W. H. Auden 📚

summing up and moving forward

What are the key elements of this ongoing project I’m calling Invitation and Repair? And of what I have called The Year of Repair? I’ll proceed by summarizing but also linking to posts and tags in which I have explored these matters more fully.

First of all, I&R is an account of cultural renewal that also strives to articulate a theology of culture. (This articulation will be done in a digressive and improvisatory way, a way that tries to be open to unexpected transmissions, that leans into the possibility of stochastic resonance.)

Second: Michael Oakeshott has said that a culture is, among other things, “a manifold of invitations to look, to listen, and reflect.” This is profoundly true, and it’s important that he said it in a lecture about the character of the university. The American university today is impatient with looking, listening, and reflecting, and instead wants to move immediately to (a) the bureaucratic implementation of some half-baked notion of Justice, or (b) the translation of scientific inquiry into monetizable Product, or (c) the enabling of the fulfillment, according to the logic of metaphysical capitalism, of any given Self. What’s needed, for culture to be renewed, is a turn away from the trinity of Justice, Product, and Self and a return to the holier trinity of looking, listening, and reflecting. It is to these activities that I wish to invite people.

Third: A useful means of promoting this invitation is to suggest that one’s attention might profitably be redirected from the exigencies of the present moment to the rich variety of the past: that we might initiate our project of looking, listening, and reflecting by “breaking bread with the dead.”

Fourth: One of the ways to break bread with the dead — and even to break bread with those who are still around but just older — begins with resisting the temptation to discard and replace. The idea that replacement is better than repair is endemic not just to our economic order but to our entire social order. (People discard and replace friend, spouses — hell, people discard their old selves and replace them with shiny new ones, or simulacra thereof. That’s the hard heart and impoverished soul of metaphysical capitalism.)

So let’s start here, with something basic and self-helpy:

When you can manage it, hit the pause button: look, listen, and reflect.

And when you can’t manage it, when you are positively itching to do something, look for something to fix:

- An old guitar that just needs cleaning and restringing;

- A pair of rusty garden shears (growing things in general — gardens, lawns, houseplants — yield wonderful opportunities for fixing and fixing up);

- A shirt that needs buttons resewn;

- A personal website that has gotten weedy with buggy code and dead links;

- A friendship that (as Samuel Johnson puts it) has fallen into disrepair;

- A favorite book that needs the particular kind of repair that we call attention.

This article by Cal Newport says it’s about “slow productivity,” but as far as I can tell it’s really about “workplaces assigning less work.” Which is, IMO, a totally different thing.

all I want to know is ...

… How many would be too many? Just give me a number. How many times does this have to happen before Arteta thinks, You know, maybe this guy isn’t really helping us? That’s all I want. I want to know the number.

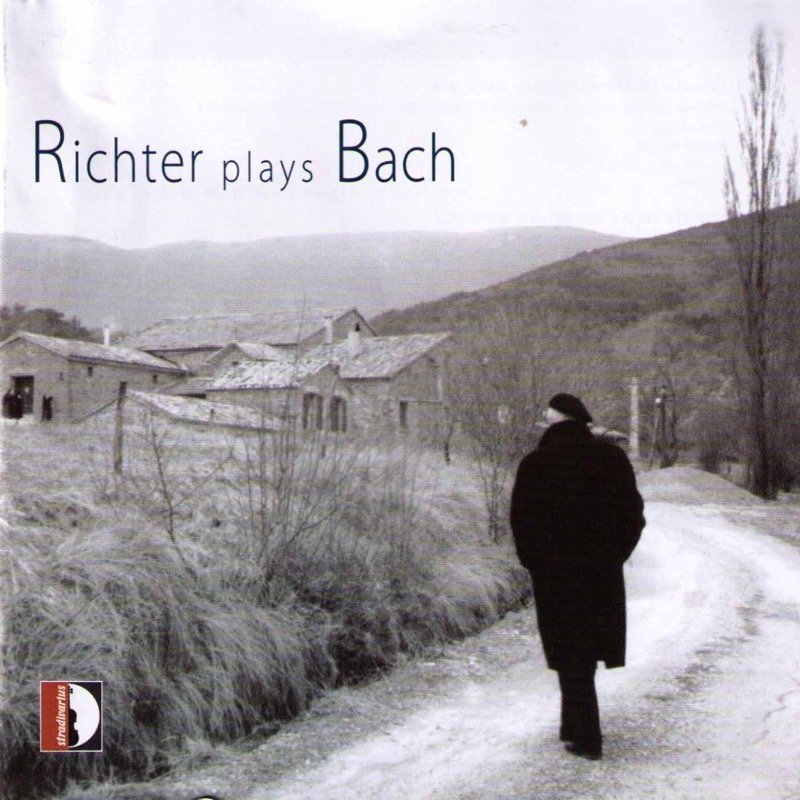

revisiting Richter

A couple of weeks ago I compared Sviatoslav Richter’s playing of Bach unfavorably to Glenn Gould’s. I need to revisit that comparison. I was basing my response to Richter solely on his recording of The Well-Tempered Clavier, but recently I have been listening to his massive Richter Plays Bach set and I am absolutely blown away.

The problem with Richter’s Well-Tempered Clavier, I now realize, has nothing to do with Richter’s playing: it’s all about the recording. The performance sounds like it was recorded in a large room, maybe even on a stage in a concert hall. The reverberations of the environment give the recording a kind of … well, almost pompous quality, a kind of unwarranted drama, given the studious (even if often playfully studious) character of Bach’s exercises. Gould’s recording technique, with its famously close miking, is a much better fit for the music.

Richter Plays Bach is not as closely-miked as Gould’s performances tend to be, but it was obviously recorded in a more intimate environment than The Well-Tempered Clavier was — and, it turns, out, that makes an enormous difference. The warmth and intelligence of Richer’s playing just sing out. His articulation, though not as absolutely precise as Gould’s — no one’s is, Gould is precise sometimes to a fault —, is flawless, but exhibits an absolute mastery of subtle dynamics as well. And I can hear all this because the recording is so well-engineered. What a masterpiece — I really do think this will become one of my favorite recordings.