moral infections

That it is at least as difficult to stay a moral infection as a physical one; that such a disease will spread with the malignity and rapidity of the Plague; that the contagion, when it has once made head, will spare no pursuit or condition, but will lay hold on people in the soundest health, and become developed in the most unlikely constitutions: is a fact as firmly established by experience as that we human creatures breathe an atmosphere. A blessing beyond appreciation would be conferred upon mankind, if the tainted, in whose weakness or wickedness these virulent disorders are bred, could be instantly seized and placed in close confinement (not to say summarily smothered) before the poison is communicable.

— Dickens, Little Dorrit

When the Pandemic’s End Means the Return of Anxiety - WSJ:

Taking an absolutist approach means assigning zero weight to all risks other than the medical one, points out Talya Miron-Shatz, a decision scientist and visiting researcher at the University of Cambridge. “This, in fact, is what every news outlet has been doing for almost a year now,” she says. “We see counts of dead, sick, hospitalized, but not of unemployed, lonely, anxious, or just losing it because so much has been taken from us — company, theaters, and mostly peace of mind. Then there are the health hazards, as people have been avoiding routine care because they feared catching Covid. These costs need to be calculated individually. There’s no easy way to quantify them, which means it’s no wonder that some people ignore them altogether, minimize cognitive effort, and just focus on Covid.”

This story, from last April, still seems relevant today.

The Year of Repair

One year and one day ago, I wrote: “I declare 2021 The Year of Hypomone.” As you’ll see if you read that post, hypomone is a New Testament word meaning “patient endurance,” and I hope we have all learned a few things about endurance in the past … well, two years. But endurance is not enough.

Today I say: I declare 2022 The Year of Repair.

This is the year when we must turn our attention not to innovation or disruption or any of the other cool buzzwords, but to fixing the shit that needs fixing.

As Steven J. Jackson has shown in an absolutely seminal essay, our situation requires “broken world thinking,” and broken world thinking leads to an imperative of repair.

We will look unflinchingly at what is broken.

We will repent of and ask forgiveness for our role in the breaking.

We will scout the landscape for the tools of repair, and be especially attentive to what we have discarded, what we have labeled as refuse. We will therefore practice “filth therapy.”

I think of these words: “Don’t be afraid, says Yeshua. Far more can be mended than you know.”

We will therefore smile, if wryly, as we sing the song of this year:

circumlocution

A memorable moment from Dickens’s Little Dorrit:

‘May I inquire how I can obtain official information as to the real state of the case?’

‘It is competent,’ said Mr Barnacle, ‘to any member of the — Public,’ mentioning that obscure body with reluctance, as his natural enemy, ‘to memorialise the Circumlocution Department. Such formalities as are required to be observed in so doing, may be known on application to the proper branch of that Department.’

‘Which is the proper branch?’

‘I must refer you,’ returned Mr Barnacle, ringing the bell, ‘to the Department itself for a formal answer to that inquiry.’

‘Excuse my mentioning — ’

‘The Department is accessible to the — Public,’ Mr Barnacle was always checked a little by that word of impertinent signification, ‘if the — Public approaches it according to the official forms; if the — Public does not approach it according to the official forms, the — Public has itself to blame.’

One can discover the proper branch of the Circumlocution Department to address one’s inquiries if one goes to the Circumlocution Department and asks. Assuming, of course, that one addresses that inquiry to its proper branch.

Recently I had a medical problem that needed attention, and so — naturally enough, one might think — called the clinic that handles my primary care. I was (a) told by a robotic voice that I was caller 17, that is, that they would get to me only after they had handled the inquiries of sixteen other people, and (b) asked by a different voice whether I knew that I could make an appointment online.

I hung up and got online, where I requested an appointment. Several days of silence ensued, at the end of which I got a message telling me that if I wanted an appointment I needed to call the office. I did, and heard a robotic voice telling me that I was caller 23….

Two weeks later, I discovered that a member of my family, who has a serious medical condition, was told at the doctor’s office that she had no health insurance. I called the Benefits department of Baylor’s Human Resources — though later I discovered that I was not talking to another Baylor employee, but rather to a representative of a company to whom Baylor has farmed out such responsibilities — and was told that I could not be helped over the phone, no matter how urgent the situation, but had to submit a request for clarification (and, ultimately, coverage) to a particular email address.

I dutifully took down the email address and sent my inquiry. The email address did not exist.

I called back, got from a different person a different email address. That address too did not exist.

I went online to the company’s website and found a chatbot that gave me a third email address. This one worked. Indeed, within seconds I got a reply email telling me that if I had an urgent request I should call at a particular number — the number I had originally called.

It’s important to recognize that what I went through in both of the circumstances did not result from bugs in the systems, but from features — from purposeful design. The goal of all our contemporary Departments of Circumlocution is simply this: To make us give up. To bring us to the point of shrugging our shoulders and crossing our fingers in the hope that whatever illness we have will somehow get better; or to the point that we pay for medicine ourselves because we can’t figure out how to get our insurance to cover it, and don’t dare try to get by without it. The object of these systems is the generation of despair. Because if the systems make us despair then the companies that deploy them can boast of the money they have saved the organizations that purchase their services.

A number of trees here are convinced that it’s still autumn.

practices

In an earlier post I mentioned Lauren Winner’s book The Dangers of Christian Practice. Let me try to summarize that book’s argument:

For a very long time it was characteristic of Protestants (pastors, theologians, ordinary laypeople) to see Christianity as a matter of the heart — or, perhaps, as an orientation of the will towards God. This was accompanied by a denigration of classic Christian practices — prayer, fasting, penance, silence — as merely external manifestations of religiosity. Then came a “repristination” of traditional Christian practices: “When a Christian theologian (or a ‘popular’ Christian devotional writer) writes about a ‘Christian practice,' she is almost always commending something to you.” What’s missing from this commendation is the possibility — indeed, the inevitability — that even the most essential and time-honored practices will go awry. For instance, celebrations of fasting rarely if ever acknowledge the ways that for some people fasting can become entwined with eating disorders. What’s required now is a depristination of practice: an awareness of the ways that the cultivation of Christian practices does not escape our sinfulness and brokenness — that such cultivation will necessarily lead to “characteristic damage,” damage not incidental to such practices or occurring thanks to a deviation from them, but rather intrinsic to their embrace by sinners.

Now, Winner makes many important caveats along the way: that she is not making an argument against the cultivation of traditional Christian practices, that by the grace of God even “damaged gifts” can bring blessing. With the arguments and the caveats taken together, this is an important book, and clearly correct in its chief points.

So. Now what?

- Among certain non-Catholic Christians, there is a kind of sentimentality about “Catholic” practices. Get over it. No practice, no church, no denomination, no communion, allows You to escape You.

- Properly chastened — and properly aware of the particular dangers of the practices that allow you to do what you would want to do anyway — continue to cultivate them. They have arisen and been developed over many centuries for Reasons.

- Long ago Stanley Hauerwas, in response to the frequently-heard insistence that “the Christian church needs a social strategy,” insisted that the Christian church is a social strategy. Christians who in good faith and with self-skepticism practice the traditional Christian disciplines are ipso facto pursuing a social strategy. Let’s not forget it.

- In an email to me, Leah Libresco Sargeant mentioned the recent tendency among U. S. Catholic bishops — and maybe bishops elsewhere, I don’t know — to move Holy Days of Obligation that occur during the week to Sundays. Leah commented, “I don't like shifting Holy Days of Obligation from Thursday to Sunday — it's good for sacred time to interrupt ordinary time. We need reminders of that hierarchy.” We need the practices that set us in tension with the practices of everyday life under technocratic capitalism. And we need them even if those tensions are, for us, near occasions of sin.

The Virtual Sir John Soane’s Museum is great. I love the Model Room.

two quotations on web3

Web3 aims to seize on the communicative motives of social media and fuse them more directly with transactional ones, as every interaction can be recast as a transaction backed by the blockchain.

I don’t share the same generational excitement for moving all aspects of life into an instrumented economy.

Currently reading: Little Dorrit by Charles Dickens 📚

“The Wood of Error,” from Robert Rauschenberg’s drawings of Dante’s Inferno

formation and martyrdom

Continuing here to lay the groundwork for future reflection, opening questions rather than answering them….

Lately I have been musing over something the great Fleming Rutledge wrote a month or so ago: “I don’t like the word ‘practices.’ We have a mighty, implacable, shape-shifting Enemy so we need strategies.”

I agree with this emphasis wholly, except … what if the central practices of the Christian faith themselves constitute a strategy, indeed are the essential strategy? Mightn’t those practices be like the ones that Daniel learns from Mr. Miyagi in The Karate Kid – seemingly pointless or trivial habits and skills that turn out to be the most important ones to have in a time of great need?

I think this is the point that Lessle Newbigin makes in that essential book The Gospel in a Pluralist Society:

Because Jesus has met and mastered the powers that enslave the world, because he now sits at God’s right hand, and because there has been given to those who believe the gift of a real foretaste, pledge, arrabōn of the kingdom, namely the mighty Spirit of God, the third person of the Trinity, therefore this new reality, this new presence creates a moment of crisis wherever it appears. It provokes questions which call for an answer and which, if the true answer is not accepted, lead to false answers. This happens where there is a community whose members are deeply rooted in Christ as their absolute Lord and Savior. Where there is such a community, there will be a challenge by word and behavior to the ruling powers. As a result there will be conflict and suffering for the Church. Out of that conflict and suffering will arise the questioning which the world puts to the Church. This is why St. Paul in his letters does not find it necessary to urge his readers to be active in evangelism but does find it necessary to warn them against any compromise with the rulers of this age. That is why it was not superiority of the Church’s preaching which finally disarmed the Roman imperial power, but the faithfulness of its martyrs.

The question then is: How to form Christians in such a way that they are capable of undergoing martyrdom? (In any of its forms: red, green, or white.)

I am convinced that this is indeed a matter of cultivating the proper practices – which include words and deeds alike, by the way, or rather speech and writing understood as deeds: as Newbigin goes on to say, the fact that the witness of the martyrs was so exceptionally powerful does not abrogate the need for faithful preaching – indeed, faithful preaching was surely one of the means by which the martyrs were formed: “The central reality is neither word nor act, but the total life of a community enabled by the Spirit to live in Christ, sharing his passion and the power of his resurrection. Both the words and the acts of that community may at any time provide the occasion through which the living Christ challenges the ruling powers. Sometimes it is a word that pierces through layers of custom and opens up a new vision. Sometimes it is a deed which shakes a whole traditional plausibility structure. They mutually reinforce and interpret one another. The words explain the deeds, and the deeds validate the words.”

Preaching and praise, fasting and penitence, reading and serving – all are core practices of the Church. But as Lauren Winner has convincingly and troublingly argued, that may be more complicated than it sounds. More on the difficulties in a later post, I suspect.

Sidney was right

I conclude, therefore, that [the poet] excels history, not only in furnishing the mind with knowledge, but in setting it forward to that which deserves to be called and accounted good; which setting forward, and moving to well-doing, indeed sets the laurel crown upon the poet as victorious, not only of the historian, but over the philosopher, howsoever in teaching it may be questionable. For suppose it be granted — that which I suppose with great reason may be denied — that the philosopher, in respect of his methodical proceeding, teach more perfectly than the poet, yet do I think that no man is so much Philophilosophos as to compare the philosopher in moving with the poet. And that moving is of a higher degree than teaching, it may by this appear, that it is well nigh both the cause and the effect of teaching; for who will be taught, if he be not moved with desire to be taught? And what so much good doth that teaching bring forth — I speak still of moral doctrine — as that it moves one to do that which it doth teach? For, as Aristotle says, it is not Gnosis but Praxis must be the fruit; and how Praxis cannot be, without being moved to practice, it is no hard matter to consider. The philosopher shows you the way, he informs you of the particularities, as well of the tediousness of the way, as of the pleasant lodging you shall have when your journey is ended, as of the many by-turnings that may divert you from your way; but this is to no man but to him that will read him, and read him with attentive, studious painfulness; which constant desire whosoever has in him, has already passed half the hardness of the way, and therefore is beholding to the philosopher but for the other half. Nay, truly, learned men have learnedly thought, that where once reason has so much overmastered passion as that the mind has a free desire to do well, the inward light each mind has in itself is as good as a philosopher’s book; since in nature we know it is well to do well, and what is well and what is evil, although not in the words of art which philosophers bestow upon us; for out of natural conceit the philosophers drew it. But to be moved to do that which we know, or to be moved with desire to know, hoc opus, hic labor est.

Currently reading: History of England (Volume I) by David Hume 📚

The reality is that for many people, publicly expressing ideology is not about trying to say what's right and wrong; it's about trying to look good to others. It's moral masturbation, not moral theory. Rather than helping others — which might cost them something! — they advocate helping others. Rather than ameliorating some of the bad effects of injustice — which might cost them something! — they advocate for justice. They then consume the warm glow of cheap altruism and earn the admiration of like-minded peers, all while living a self-centered luxury lifestyle.

The George Mason University economist Tyler Cowen once noted that in the United States, cities' politics and behavior seem to be at odds. Egalitarian cities with fairly equal distributions of income tend to have a conservative ethos, while cities that have massive disparities in wealth and that shower rewards upon high-status people — such as Los Angeles and New York — tend to have left-wing and egalitarian ideologies. One possibility is that wearing a left-wing ideology is a sort of cover for living a right-wing life. Perhaps this partly explains why elite universities are so left-wing. They sell elite status, but they cover this up with incessant praise of social justice. It could be that Harvard is a right-wing institution that undermines social justice, but if it never stops talking about equality, maybe you won't notice.

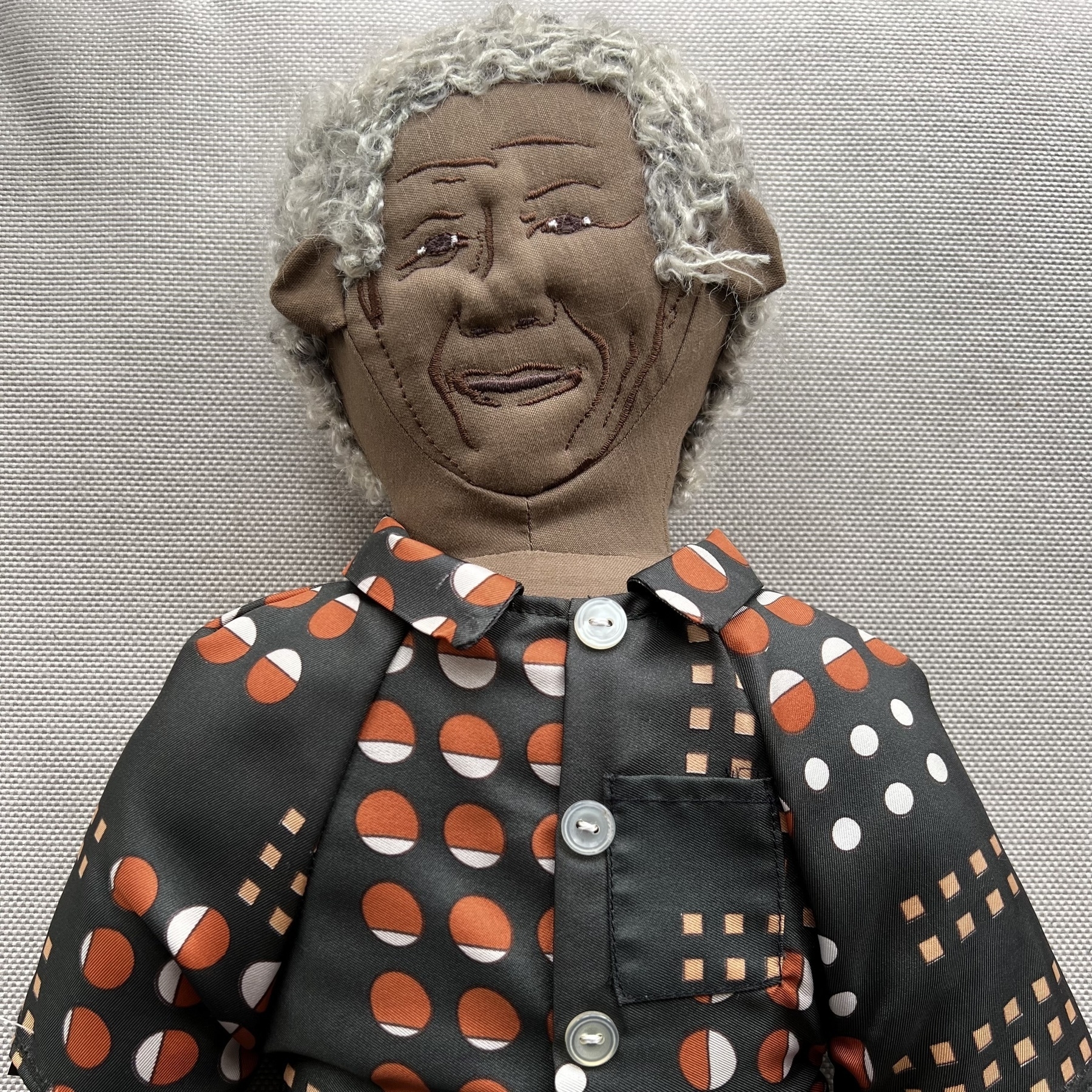

We found our old friend Nelson! – missing for many years. (Long ago a friend from South Africa gave him to us.)

Currently reading: The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins 📚

Chilly and lovely morning in the neighborhood today.

No, secularism cannot reassure us that the universe is governed by a benevolent deity, or that the wicked will be punished and the good rewarded, or that our souls will be clasped after death in the bosom of Abraham. But in leaving us to our devices, it does something better, because it does something truer. It forces us into the search: for truth, for beauty, for justice.

The notion that secularism forces some unspecified “us” into searching for truth, beauty, and justice is a purely religious notion; and a more spectacular example of wishful thinking than any other religion has ever managed to put forth.

Our ancestors, right up to the modern age, knew they were fragile. A brief period of dazzling technological achievement combined with the absence of any major global war produced the belief that fragility was on the retreat and that making our global environment lastingly secure or controllable was within reach. But the same technical achievements that had generated this belief turned out to be among the major destabilising influences in the material environment. And the absence of major global conflict sat alongside the proliferation of bitter and vicious local struggles, often civil wars that trailed on for decades. But perhaps it is only in the past two decades that we have quite caught up with the realisation that global crises are indifferent to national boundaries, political convictions and economic performance. The vulnerability cannot be neatly cordoned off.

For the foreseeable future, we shall have to get used to this fragility; and we are going to need considerable imaginative resources to cope with it. In the past, people have found resources like this in art and religion. Today it is crucial to learn to see the sciences as a resource and not a threat or a rival to what these older elements offer. It is more than high time to forget the phoney war between faith and science or art and technology.