For me, the competition for Best Wodehouse Novel comes down to The Code of the Woosters and Uncle Fred in the Springtime. Uncle Fred, more properly Frederick Altamont Cornwallis Twistleton, 5th Earl of Ickenham, is my favorite Wodehouse character. Here we see Uncle Fred and Lord Emsworth trying to convince an acquaintance of Uncle Fred’s, a con man named Claude “Mustard” Pott, to transport and hide Emsworth’s prize pig, the Empress of Blandings … for reasons too complex to get into here.

The clouds gathered once more when Mr Pott, having listened to Lord Emsworth’s proposal, regretfully declined to have anything to do with removing the Empress from her sty and wafting her away to Ickenham Hall.

‘I couldn’t do it. Lord E.’

‘Eh? Why not?’

‘It wouldn’t be in accordance with the dignity of the profession.’

Lord Ickenham resented this superior attitude.

‘Don’t stick on such beastly side, Mustard. You and your bally dignity! I never heard such swank.’

‘One has one’s self-respect.’

‘What’s self-respect got to do with it? There’s nothing infra dig about snitching pigs. If I were differently situated, I’d do it like a shot. And I’m one of the haughtiest men in Hampshire.’

‘Well, between you and me, Lord I,’ said Claude Pott, discarding loftiness and coming clean, ‘there’s another reason. I was once bitten by a pig.’

‘Not really?’

‘Yes, sir. And ever since then I’ve had a horror of the animals.’

Lord Emsworth hastened to point out that the present was a special case.

‘You can’t be bitten by the Empress.’

‘Oh, no? Who made that rule?’

‘She’s as gentle as a lamb.’

‘I was once bitten by a lamb.*

Lord Ickenham was surprised.

‘What an extraordinary past you seem to have had, Mustard. One whirl of excitement. One of these days you must look me up and tell me some of the things you haven’t been bitten by.’

A fantastic essay on Blake’s Laocoön by Adam Roberts. I must write about this at some point….

In one of the Nero Wolfe books Archie Goodwin calls his typewriter the “alphabet piano,” so that’s what I’m gonna call my computer keyboard from now on.

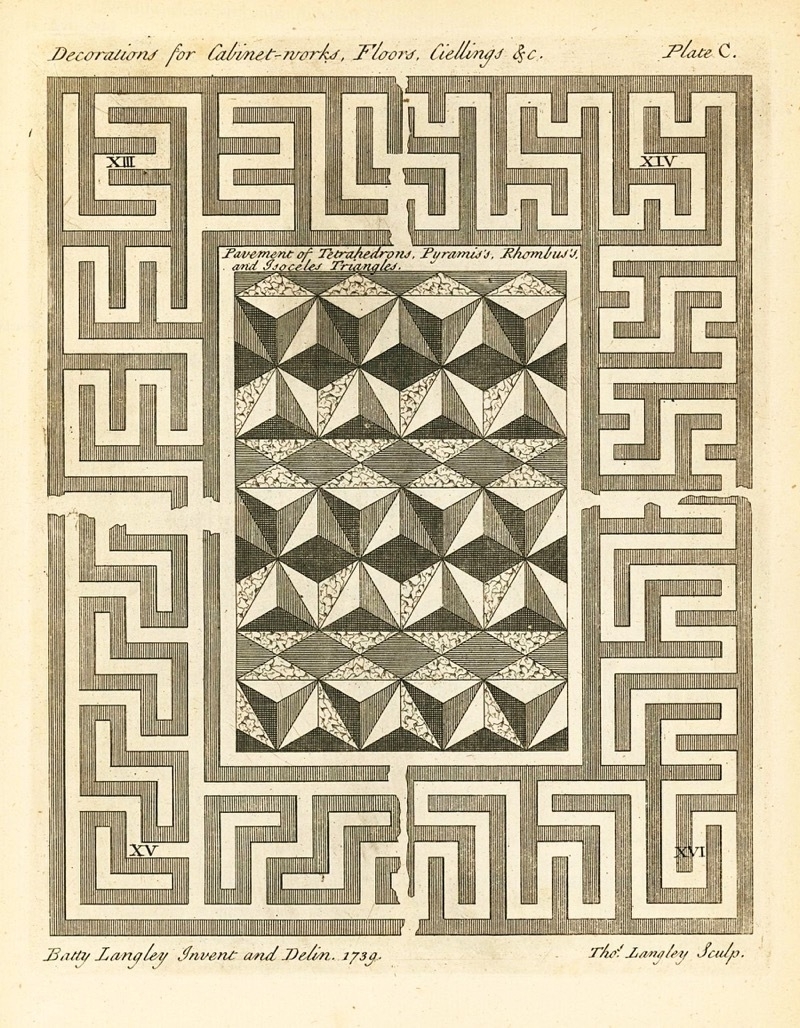

Architectural designs from The City and Country Builder’s and Workman’s Treasury of Designs by English garden designer Batty Langley (1696-1751)

Civil-official husu, Korea (19th century)

Some people will struggle to believe that I did this, but I wrote about Auden’s bad wrong essay on detective fiction.

ONE-NIL TO THE ARSENAL ⚽️

My ol’ buddy Chuck Mathewes writing brilliantly about Alasdair MacIntyre:

It was the spring semester of 1991, my senior year at Georgetown University, and my capstone seminar was dedicated to reading everything the Scottish-born philosopher had written up to that point. (It was a lot.) At the end of the semester, he came for a full day of discussion. To call it “vigorous” and “frank” would suggest we were auditioning for the State Department.

As I recall, he mocked those who did not like the Red Sox (or possibly those who did?). At another point, he suggested that, if we were in Ireland, he would have been entitled to kill one of my classmates.

Undoubtedly, though, the most memorable moment for me came at lunch, when one of us asked him a question that was really a barely disguised invitation for him to congratulate us on our class's dedication to his writings. He was having none of it. "Oh, I think your class is profoundly misbegotten," he said. "If you had understood anything of what I have written, you would have immediately stopped reading my work and turned to an intensive study of Aristotle and Aquinas."

Steven Pinker’s new essay on Harvard is outstanding: fair-minded, well-reasoned, clearly-argued, and full of links to articles that provide copious support for his key claims.

The Taming of the Shrew, illustrated by Valenti Angelo

Phil Christman on Paul Elie's new book:

It is perfectly normal not to be able to decide whether or not we believe in a religious doctrine. It is another to act as though their truth or untruth were a matter of indifference. It matters whether or not there is such a state as enlightenment, and whether or not dharma is the purpose of human existence, and whether or not there is one good of whom Muhammad is the prophet, and whether or not Jesus rose from the dead. Some crypto-religious art is deeply powerful because the artist cannot resolve to believe or not; but lots of it is, in the precise Frankfurtian sense, bullshit because the artist doesn’t really care. I would, for example, respect Andres Serrano — the photographer who famously immersed a crucifix in a jar of urine and found himself the victim of an old-fashioned right-wing witch hunt — far more than I do if he simply said that “Piss Christ” is an attempt to rile people up. The line that Elie takes here is that “Piss Christ” “stood on the threshold, in liminal space: inside and out, religious and not,” and he quotes Serrano, with seeming approval, as saying that the work expresses “something inside of me that had to come out.” What exactly does it express? That getting crucified is like getting peed on nonconsensually? That urine can be kind of pretty, depending on a person’s hydration levels and the mineral content of their diet, if you photograph it just right, and if you don’t tell people right away that it’s urine? I call bullshit, unless “something inside of me that had to come out” is simply Serrano joking about the urgency of one’s need to go.

Alasdair MacIntyre: Lux æterna luceat ei, Domine.

Finished reading: What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade, which I wrote about, at some length, here. 📚

I wish tech writers were more consistently mindful of the distinction between (a) announcing the development of a product and (b) actually shipping that product — and then, if the product ever is shipped, between (a) the claims a company makes for its product and (b) what the product actually does.

Coming soon

Kafka announced to us long ago that the meaning of life is that it stops. True enough. But [Jennifer] Banks walks the reader alongside seven intellectuals who took seriously the bookend of starting: new life, fecundity and generativity — and, in my mind, our many distributed practices of creative midwifery that get new ideas off the ground. Hannah Arendt is one of Banks’s chief companions on natality. She thought our creative beginnings are not just universal but necessary, a strong stance against authoritarianism, a rebuke to brute force power. Natality, for Arendt, embodies the amor mundi, an outwardness and expectation of beginnings, of making room for others. She called it “the miracle that saves the world, the realm of human affairs, from its normal ‘natural’ ruin.” And the amor mundi has to start somewhere. Not just the endless talking about what the world should be like. Prototyping is beautifully restless and insistent: Show me how. Let’s start.

John Siracusa: “The recent Apple Intelligence fiasco has revealed that the company is further away from properly prioritizing software reliability than it has ever been. Apple was seemingly willing to sacrifice everything, including its own reputation, to ensure that it had enough new AI features to announce at WWDC. If we want a different result, it seems like we need different leaders.”

Magnolia season