Ancient writers at their desks. Even back then some people knew how to apply ass to chair.

My dear friend Wesley Hill has written a lovely brief book about Easter.

[In the seventeenth century] John Aubrey, the first person to make a serious study of stone circles, put his finger on the problem: ‘These Antiquities are so exceeding old that no Bookes doe reach them.’ He developed a more effective method. Using measurements and comparative surveys of different circles with notes ‘writt upon the spott’, he was able to work out that megalithic monuments were of distinct types and that they predated the Romans, Saxons and Danes. He thus, almost single-handedly, created the concept of prehistory and invented field archaeology.

Re: Oliver Burkeman’s 70% rule — “If you’re roughly 70% happy with a piece of writing you’ve produced, you should publish it. If you’re 70% satisfied with a product you’ve created, launch it” etc. — nothing could be more alien to how my mind works than the quantification of mixed feelings.

Hey kids! Let’s play Uranium Rush! Don’t forget the Geiger counter!

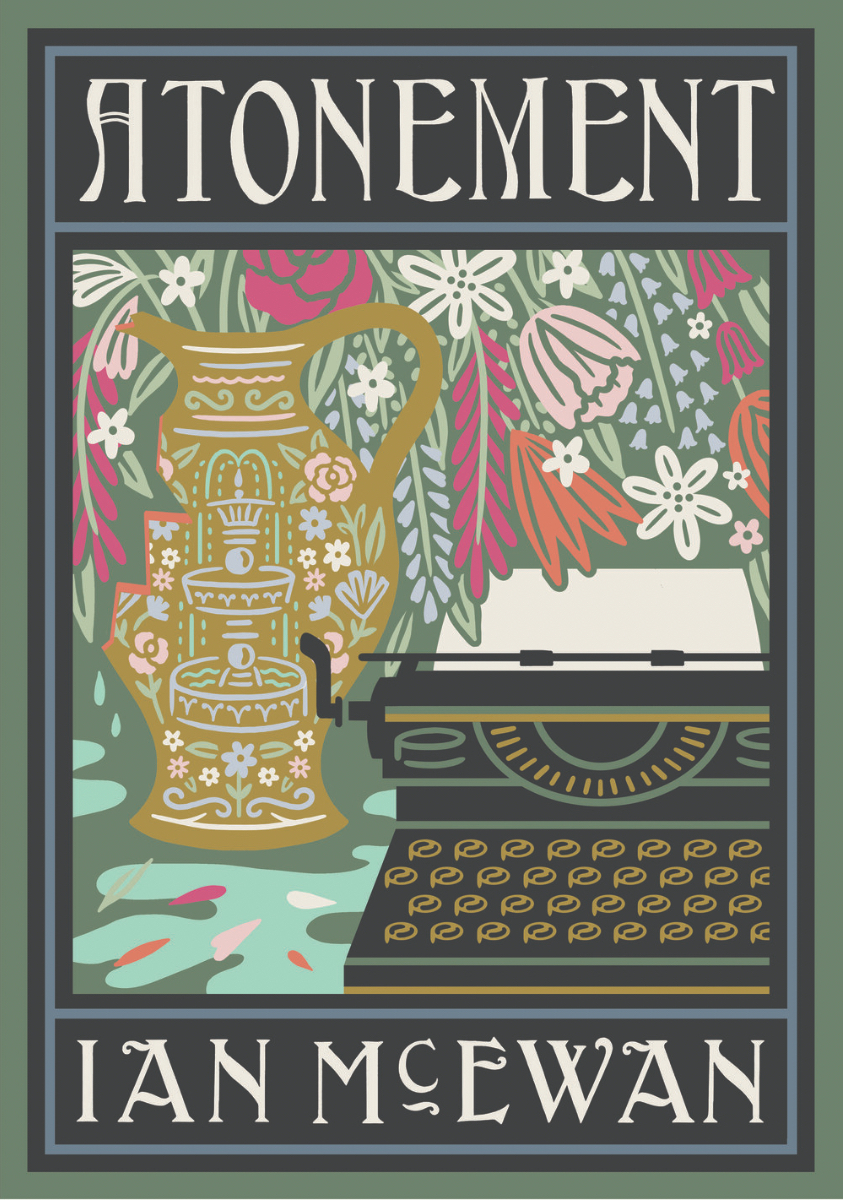

Next month I’ll be leading a retreat at Laity Lodge where the artist-in-residence will be Dana Tanamachi. Her “book covers” that illustrate Michiko Kakutani’s Ex Libris are just wonderful. And she did an illuminated Bible! — which I have a copy of and really love. It’ll be an honor to work with her.

Over at my big blog, I wrote a couple of Kane-related posts: one on an interesting audio technique, and one on what Mank did and didn’t do.

“Mister Kubrick, I’m ready for my close-up”

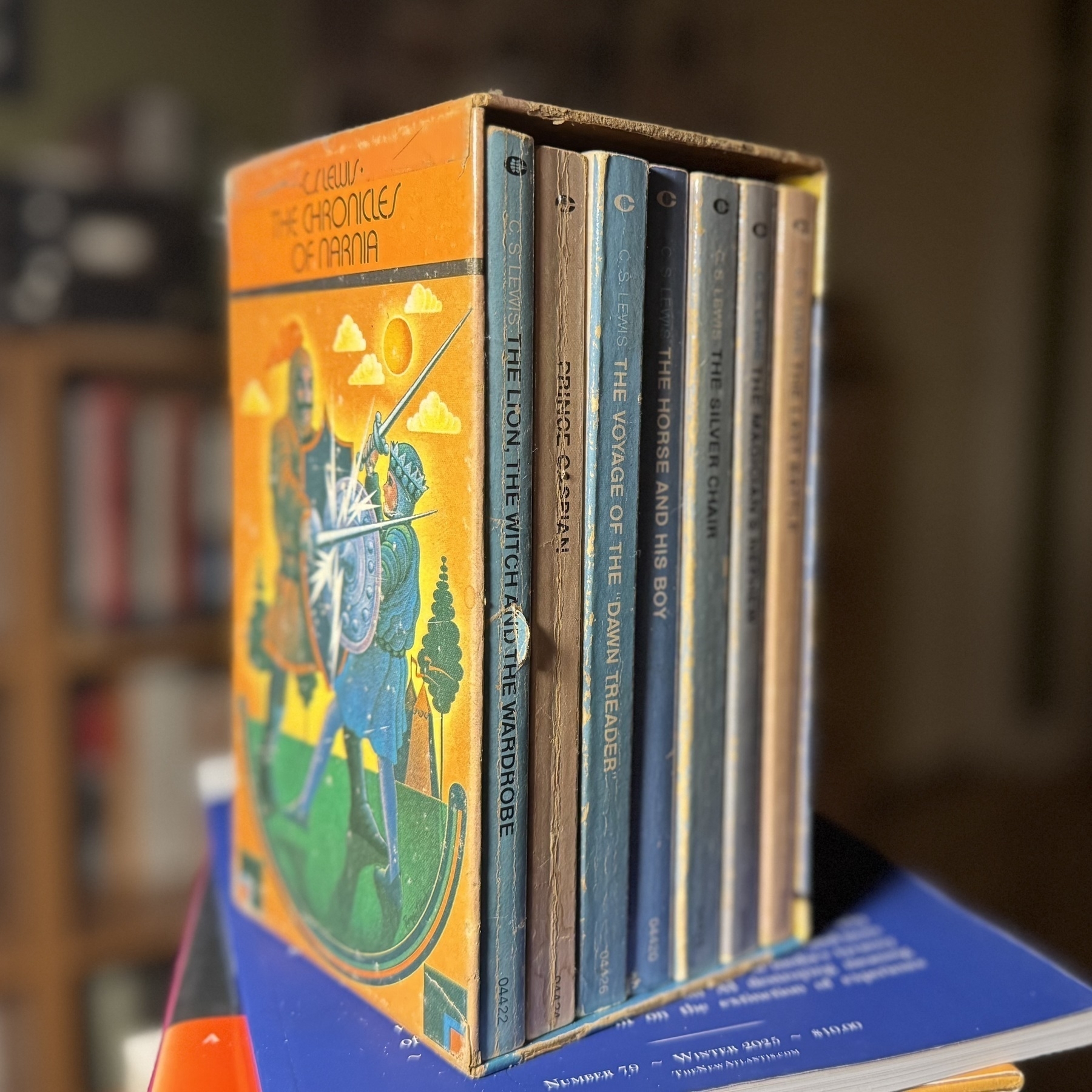

I’ve kept this boxed set around for nearly fifty years just so I can show people the order the Narnia books are meant to be read in. CC: @frjon

I wrote about the best alternative to “trying to get Management to take your side”: persuasion.

As I pulled into the parking garage this morning I had the strangest feeling that I was being watched.

I’ll just say one thing before putting this phone in another room: It’s remarkable how many usable hours there are in a day when you’re not farting around on the internet.

Related: Prayer v. Electricity

Watching Hou Hsiao-hsien’s The Assassin (2015) is like watching a wuxia movie made by Tarkovsky. I’ll have to see it at least once more before I know precisely what I think about it, but it’s certainly one of the most gorgeous films I’ve ever seen. (Shot on film 🎥, hooray)

For people who want to understand our moment not just in terms of politics, but also in historical, moral, and spiritual terms, this essay by Mana Afsari is absolutely essential. (Also, essays like this are the very raison d’être of The Point.)

Note to self: Add chapter to Sayers biography:

The intersection of Dorothy L. Sayers’ detective fiction with advanced technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) and virtual reality (VR) symbolizes more than just a transformation in storytelling—it represents a significant shift with profound implications for the environment, humanity, and the economy. The adaptation of Sayers’ works into immersive VR experiences and the use of AI to emulate her writing style are not simply novelties; they are harbingers of wider societal changes.

Redefining narratives through VR and AI fundamentally changes how we engage with literature and history. By creating interactive environments such as a digitally replicated 1920s London, we ignite a multisensory approach to education and cultural preservation.