My Substack account has gotten completely out of control, and I can best deal with that by deleting my account. I will soon create a new one and re-subscribe to the good stuff. If you’re on Substack and reading this, then of course yours is the good stuff.

My thoughts on Nicholas Jenkins’s magnificent new book on Auden, The Island, are in the new issue of The Hedgehog Review.

Craig Mod – AKA @craidmod.com:

Where am I typing these words? I’m sitting in a tiny café on the edge of a small city, surrounded by a lifetime of train love. Abject, unstoppable, fully-committed train and model train love. A little man behind the counter — an eighty-something year old guy who has no desire to chat with me, who can barely hear (probably why he doesn’t want to chat), and yet gets up each morning and opens his café (not for the cash at this point, as it doesn’t seem to be making any) — is running his perfect model trains around their magical track, a track that circumscribes the whole shop like locomotive hug, with beautiful handmade scenery and hand-painted backdrops. For nearly half a century, tens of thousands (hundreds of thousands? probably) of people have come here and been filled with delight. Here, an obsession transmuted into love with a side of toast. Given the age of the shop, it’s in pristine condition. The counter polished, the trains without any dust. The egg sandwich actually an omelette sandwich with a bit of jam. (Yum.) The coffee strong. The music classical. I’m the only one here. Sitting in the corner looking at this incredible scene — truly a life’s work, a work of life. This, too, a political act. We forget that. Is it crazy to say that a place like this represents a pinnacle of a life well-used? It does in my eyes. Archetypes move humanity forward and the trains are beside the point: The play is the point, the full-throttled commitment to that play, the showing up day after day for it, the dialing in of a private obsession while simultaneously giving it back to the world as a gift. Play. Something we’ve lost. Certainly in this infinitude of toxic discourse.

Here I am, as usual, trying to get us to be clear about what questions we’re asking.

A distinction that it took me a very long time to learn: what I need to write versus what I need to publish. Increasingly I find that I prefer to write out my thoughts (especially about politics) without sharing them with the world.

Marian Evans (George Eliot), from a letter to Charles Bray in 1859:

I have had heart-cutting experience that opinions are a poor cement between human souls; and the only effect I ardently long to produce by my writings, is that those who read them should be better able to imagine and to feel the pains and the joys of those who differ from themselves in everything but the broad fact of being struggling erring human creatures.

Mary Delany, paper mosaic. Ca. 1775

A decade ago, I wrote an essay about what seemed to me a strange development: the centrality of literature to many people’s Christian faith. I still think about how odd it is that thousands or even millions of people owe their faith not to pastors and sermons and churches, but to novelists and poets.

I’m always negotiating the relationship between micro.blog and my big blog, but I’m getting closer to a system in which micro.blog is a box of delights and the big blog is a Memex. Gonna try to stick with that model.

I despise Man City, but Rodri’s Ballon d’Or is absolutely deserved. He’s been the best player in the world for two or three years now.

Nick Heer: “If software is judged by the difference between what it is actually capable of compared to what it promises, Siri is unquestionably the worst built-in iOS application.” Has been true for more than a decade, will probably continue to be true for another decade.

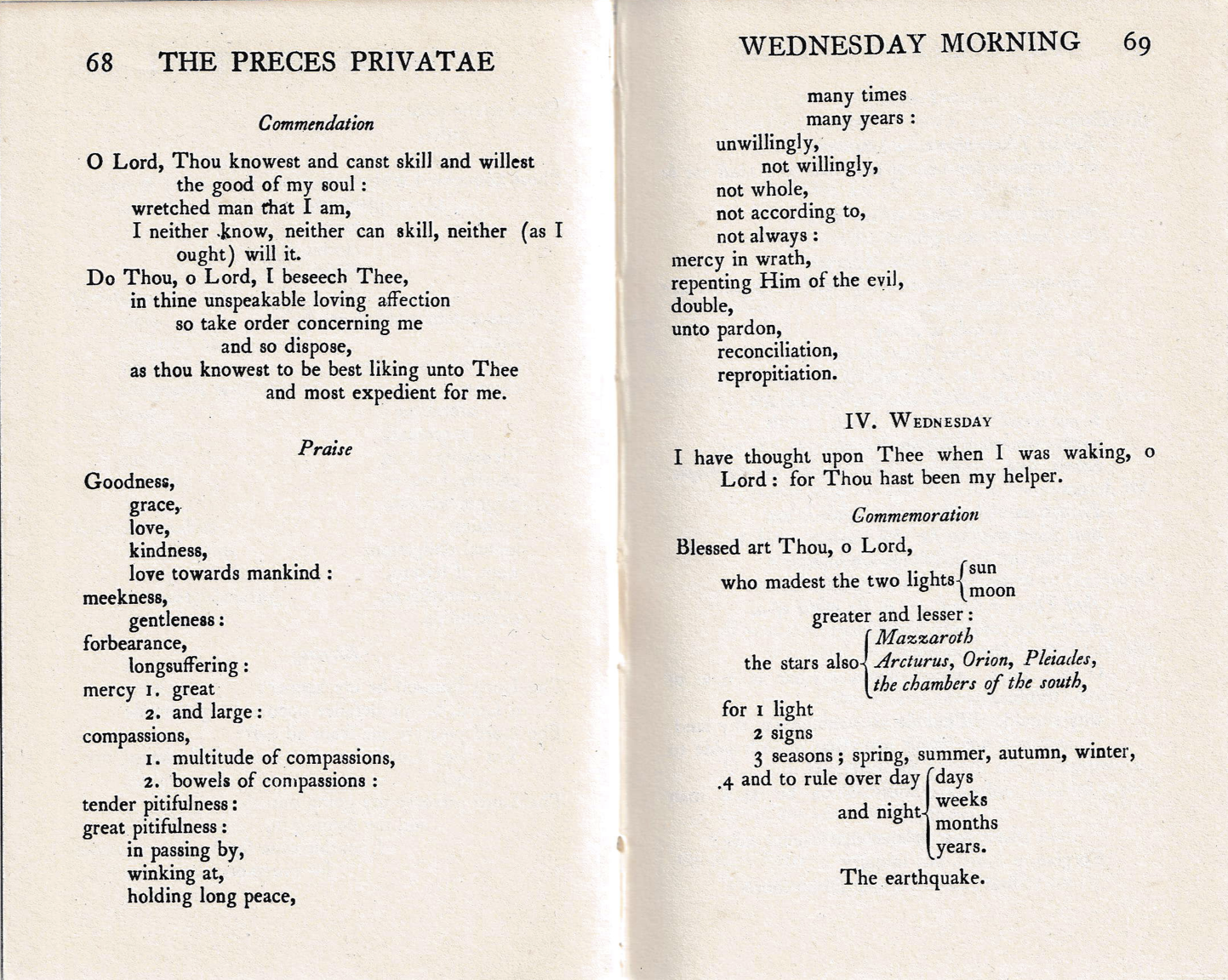

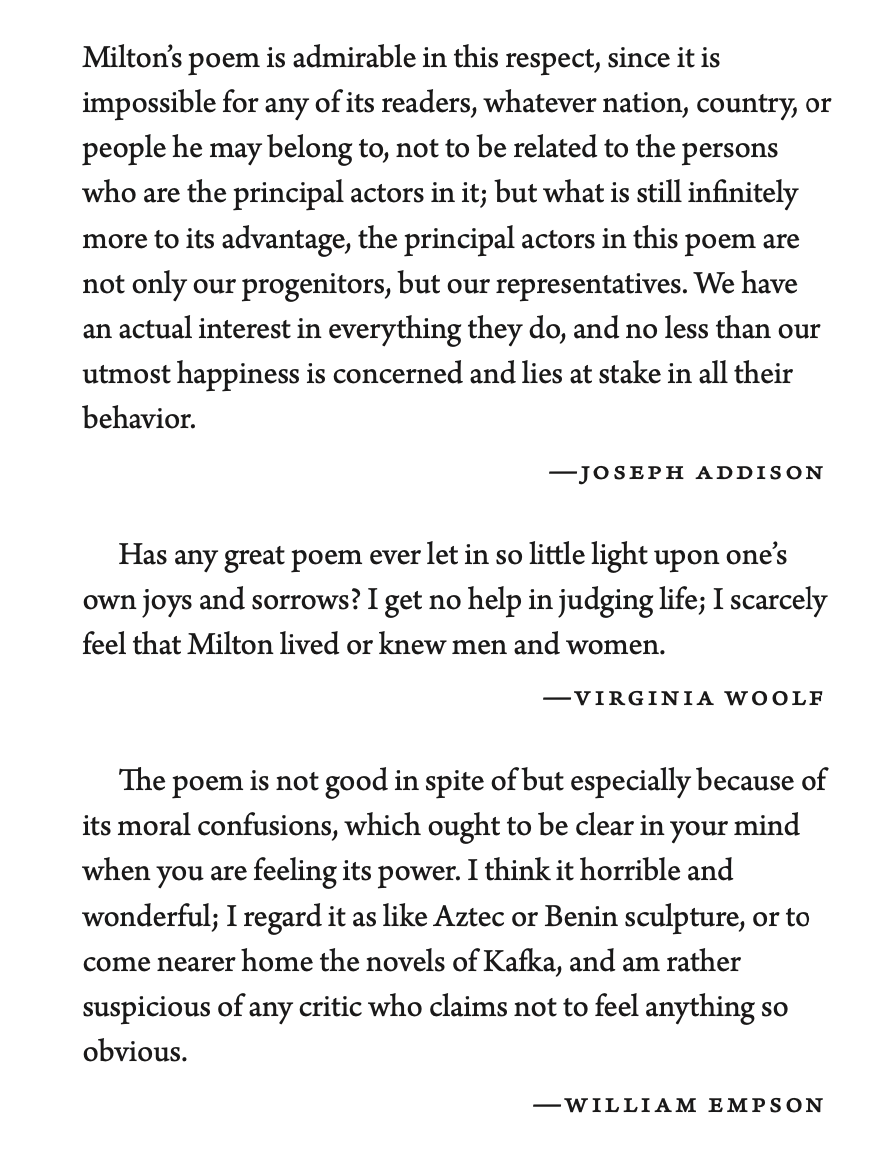

At the galleys stage of my biography of Paradise Lost — an exciting moment because I don’t have to use Word any more. Here are the epigraphs.

I wrote about articulateness — and the lack thereof — in American Presidents and Presidential candidates. Not so much about politics as about our expectations for public language.

I experience a certain vague ‘spiritualness’ within the world’s chaos, an approximate understanding that God is implicit in some latent, metaphysical way, yet it is only really in church – that profoundly fallible human institution – that I become truly spiritually liberated. I am swept up in a poetic story that is both true and imaginative and fully participatory, where my spiritual imagination can be both contained and free. The church may appear to some as small, even stifling, its congregation herdlike, yet within its architecture, music, litanies, and stories, I find a place of immense spiritual recognition and liberation.

Thinking about it now, the same can be applied to marriage – another audacious feat of the imagination – which, for some of us, like art, like faith, draws into focus what it is to love. It is order itself that allows us to be free.

Listening to: Your Mother Should Know: Brad Mehldau Plays the Beatles ♫