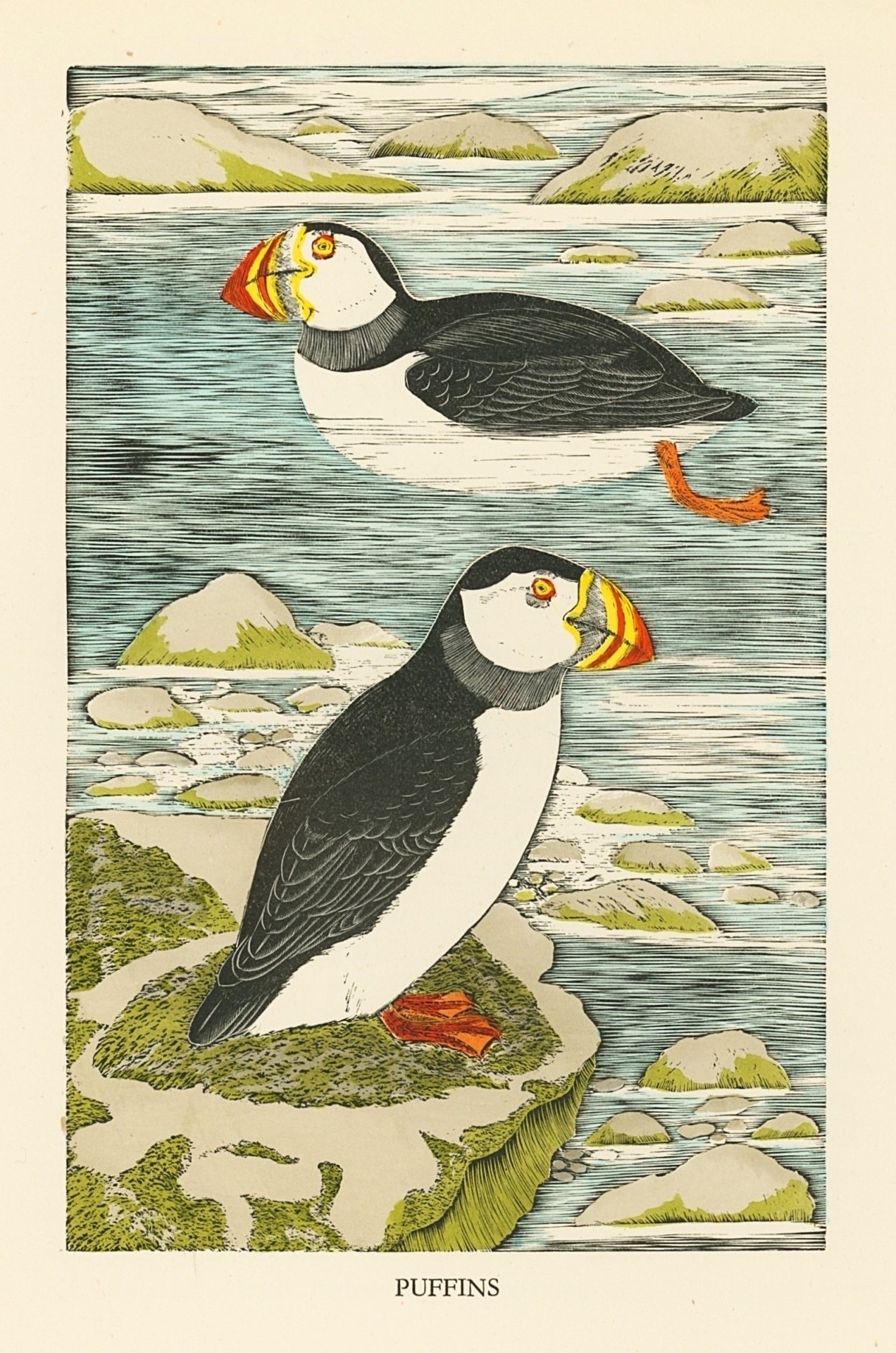

Eric Fitch Daglish, from Birds of the British Isles (1948)

Finished reading: France on Trial by Julian Jackson. A vivid and powerful story. What a unique figure Pétain is. 📚

The crisis that doctors face in their new working environment is ultimately a crisis of identity. Doctors no longer know who they are. They no longer know, for instance, if they are more than scientists or technicians. They no longer know if they are mere allies of patients or something more commanding. All is at sea in the sphere of their minds. Their doubts haunt them even when they make minor decisions. The situation will only grow worse with the next forward and downward change in medical practice: the coming of artificial intelligence. Clinical humanities will give doctors a better understanding of who they once were, are now, and might become, thereby stabilizing their sense of identity.

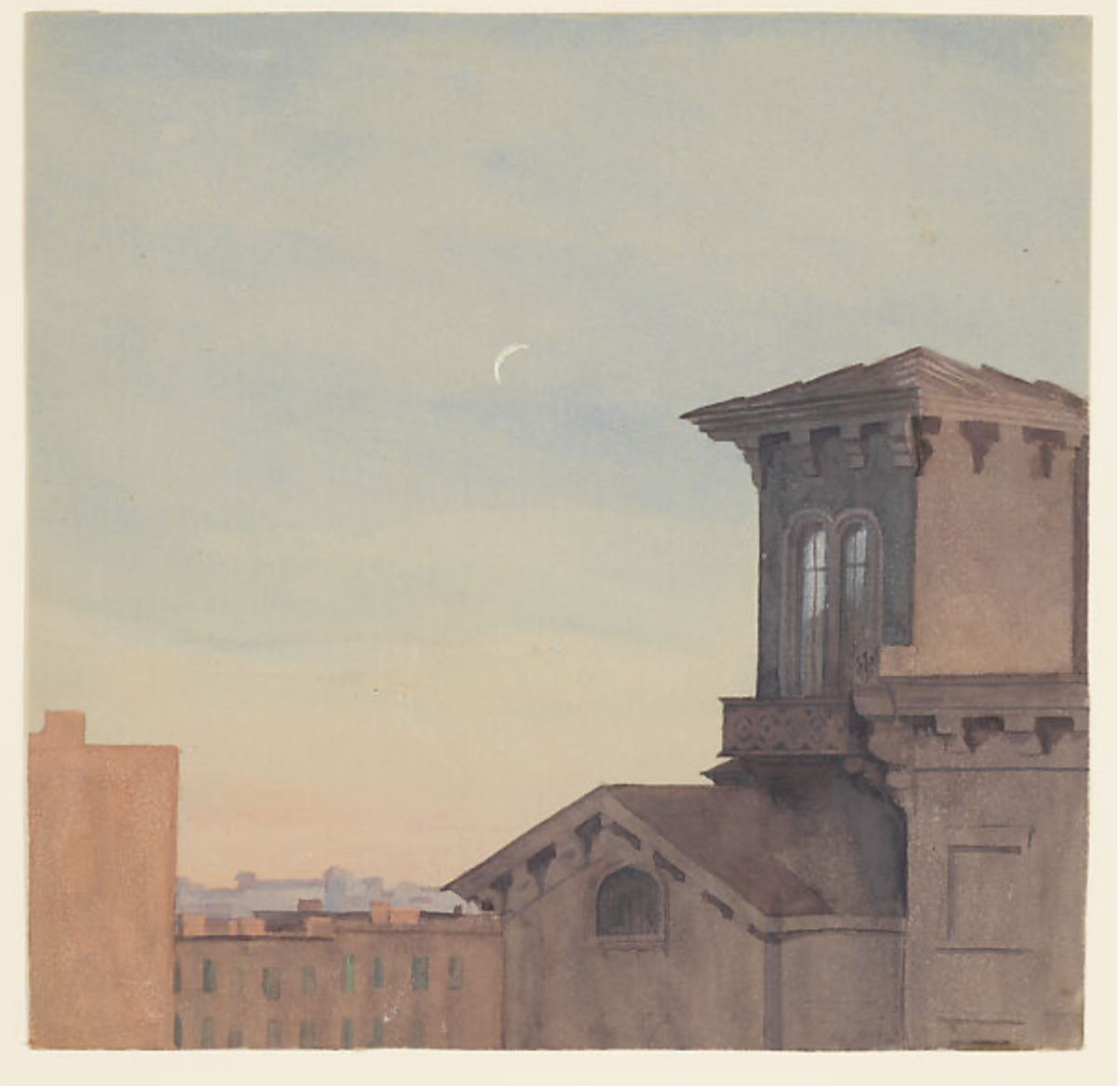

Fidelia Bridges, Rooftops, Brooklyn, ca. 1867

Everett L. Warner, New York from a Seaplane, ca. 1919

The canon of well-known classics, the books one can find in just about every library and bookstore, the books most commonly studied and written about, is like the freeway system of literature. These works have, until recently, been our most accessible and most heavily traveled routes through our literary landscape. With the creation of the Internet Archive and the steady incorporation of material into its collection, a huge amount of our literary landscape — by now a large share of the published material from the seventeenth century on — is just a few clicks away from over half the people in the world. I look forward to seeing many amazing forgotten books and writers get rediscovered and celebrated anew as more readers come to realize that so much of the literature that has historically been remote and inaccessible can now be found just steps from their front doors.

I linked to this before, I think, but I continue to listen obsessively to Alec Goldfarb’s new record Fire Lapping at the Creek — which is, let the listener beware, microtonal blues. Which is crazy, except that blues blues has microtonal elements. What a record. ♫

My writing project continues, of course. What is that project? The production of books that mix the genres and styles I love most, while adding something new — pushing those genres and styles forward — in a way that attracts a large, enthusiastic readership around the world. These books always encourage their readers to contemplate scale, in one way or another. These books make scale undeniable. That’s it! That’s the project.

Me: slightly accelerated heartbeat. You know how I feel about scale.

I find the continuing mission of Voyager 1 so moving, for the way its name alone evokes a time of promise, for the thought of that tiny contraption way out there in the vastness at the edge of the heliosphere — perhaps the farthest any human-made thing may ever travel — a bit battered, swiftly aging, still doing the work it was purposed to do.

I feel exactly the same way, but also claim a self-description: I too am “a bit battered, swiftly aging, still doing the work [I] was purposed to do.”

Very glad to see that Francesca Gino’s bullying lawsuit against the Data Colada bloggers has been quashed by a judge.

A copyright regime that precludes libraries lending scans of books they already own and care for — to loan in-copyright works sometimes, for some reasons — ultimately will curtail the circulation of culture and prevent the preservation of it in the first place. Libraries can’t save and distribute what they can’t buy outright, or convert on their own into useful new formats. Right now there is no happy medium in digital media for books, no balance between the many stakeholders involved in the transmission of the written word.

I’m thankful that Dan is fighting the good fight on this issue. But given the forces arrayed against the free exchange of ideas, this will be a hard fight to win.

This report on defamation law reminds me that I wrote an essay on the intellectual and moral history of defamation.

Zadie Smith: “I think it’s important to be a bit more forgiving when they’re being those people online. I see that too — people I love, I see them online, and I’m like, who are you? This is not the same person I hang out with. This is a different person. But it’s really important to take the responsibility and the blame off individuals. It’s a behavior modification system. It’s meant to do that. It’s really well designed. People aren’t terrible. The system is terrible. You want to lift that off people, that sense of guilt or shame, and make it more about anger — anger toward the people who created this.”

“Hello, Public Safety? There’s some dude outside my office window, just sitting there and staring in. Sitting and staring. It’s creeping me out.”

Today Robert Caro’s The Power Broker is available as an e-book, and I would love to know how many copies it will sell in that format in the first 24 hours. Book sales are such a black box, I don’t even know where to put the over/under. Maybe 15,000 copies?

Adam Roberts, “Musée des Prole Arts.”