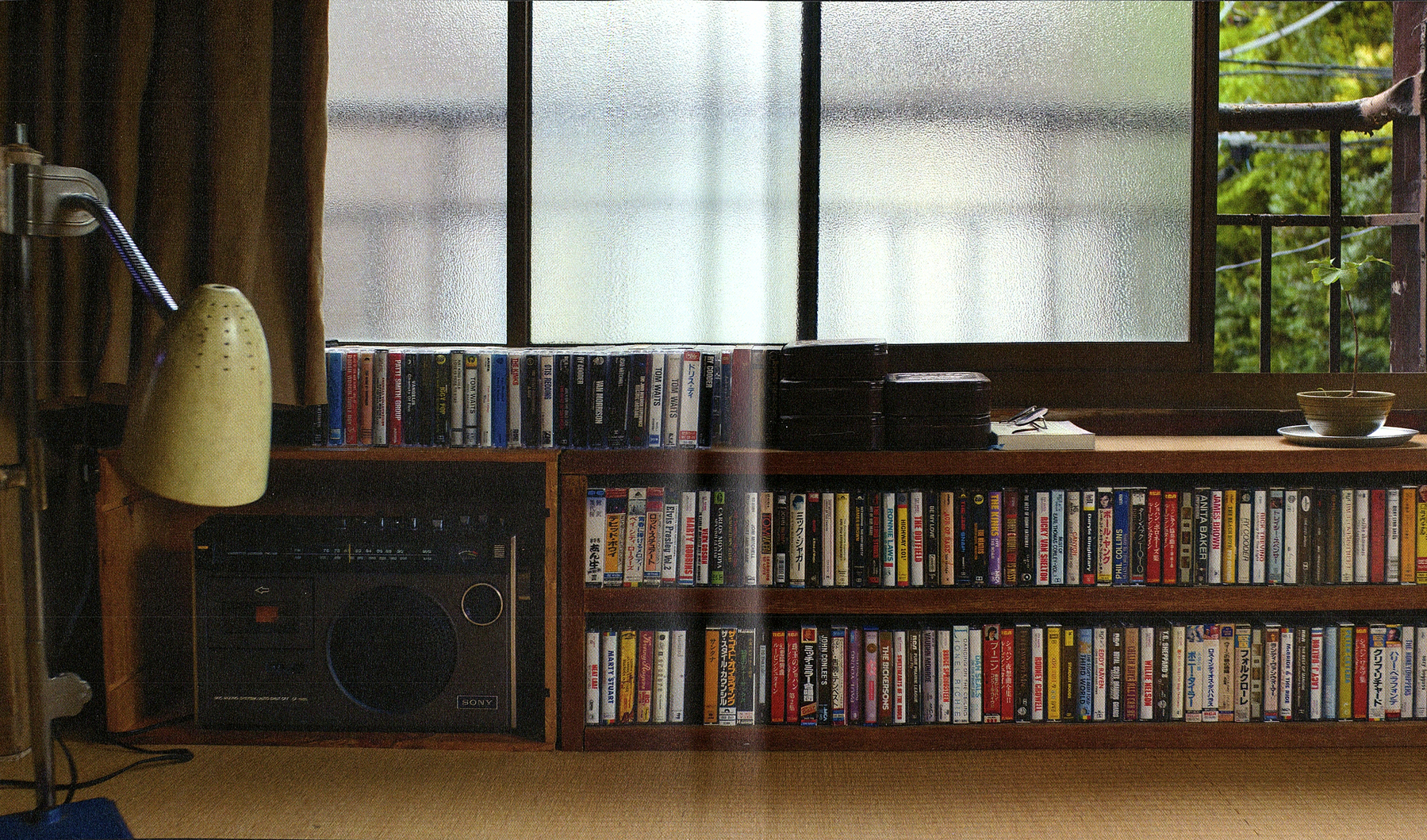

If you slip the cover art out of the plastic box that holds the Criterion edition of Perfect Days and look on the back side, you see this:

Full-size image here. (I ran that through the scanner but the folds are still somewhat visible. I apologize.)

China depicted by a 17th-century English artist – at the V&A.

Very interesting observation from Ethan Iverson:

Ross Barkan and Freddie deBoer are prolific on their Substacks; I strongly recommend subscribing to both.

Barkan and deBoer have also published essays in The New York Times within the past week. […] The articles are excellent, but they also inevitably went through the rather implacable editorial process of The New York Times. Everyone who writes for the Times ends up sounding like the Times. As a result, the exceptionally distinctive voices of Barkan and deBoer are toned down a little bit.

I became attuned to this particular topic after publishing my Gershwin essay “The Worst Masterpiece: Rhapsody in Blue at 100” in The New York Times this past February. There was at least a week of editing, with two different editors who answered to a higher third editor. After I thought I signed off everything, the final was edited further (without my oversight) and made even more “New York Times-y.”

Breaking news: VAR in the Premier League continues to be worse than useless. ⚽️

I wrote about Adam Roberts’s novel Space Satan!!! — that’s the title Adam’s son prefers and I can’t disagree.

I find that I’m not at all ready for the return of (European) footy, not after the Euros and the Olympics. I’d like another month or so to build up some excitement. ⚽️

I wrote about Sherlock Holmes and Jacques Derrida. As one does.

My all-time favorite edition of Nick Cave’s Red Hand Files is this one, about an unfortunate encounter with Charlie Watts.

Had dinner at Red Herring tonight and the cacio e pepe was, if not to die for, certainly to kill for. Okay, maybe also to die for.

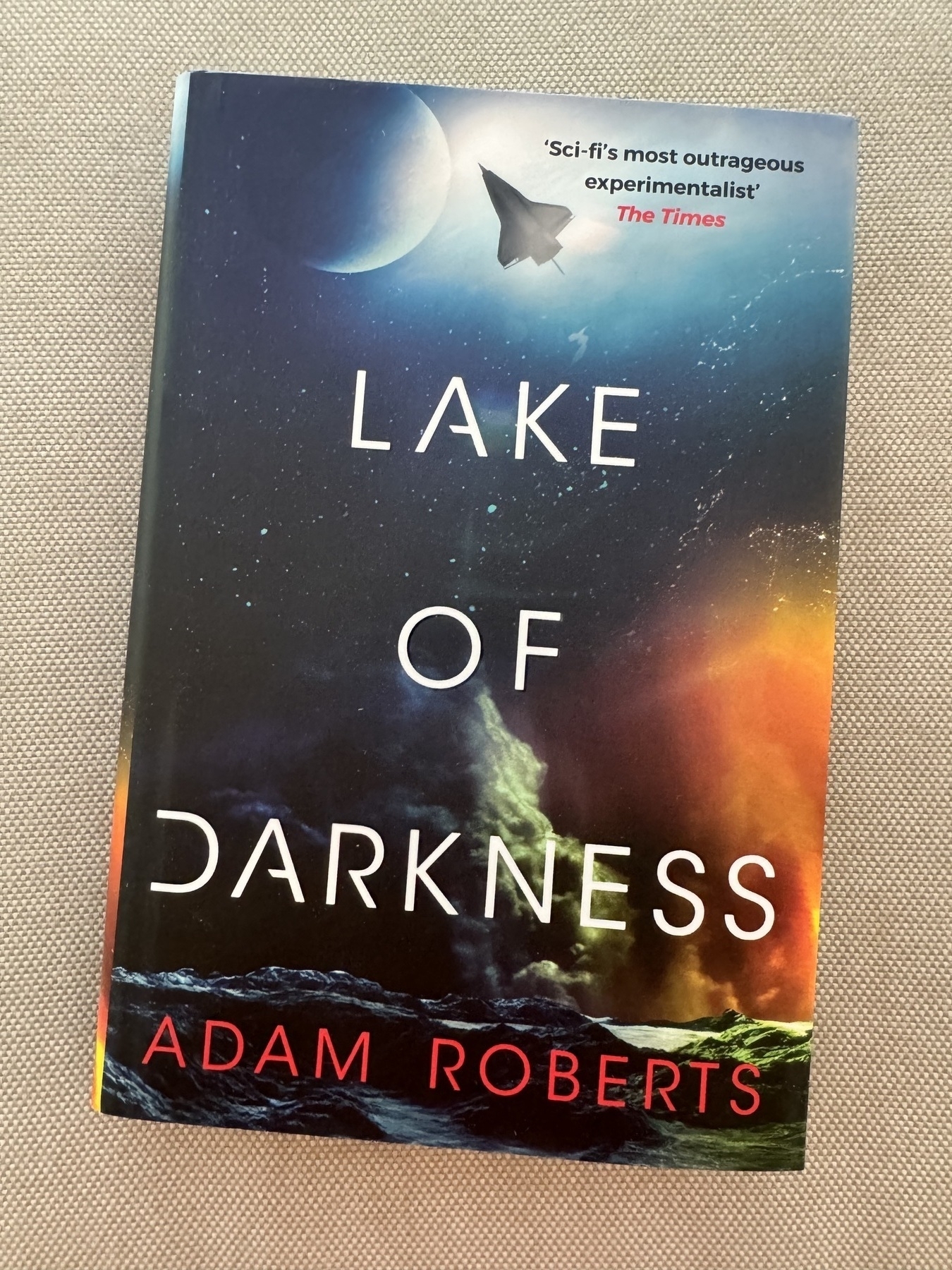

It finally arrived!

Pochettino: the only football manager on the planet who can look at the USMNT job and think: Well, it’s not as chaotically mismanaged as my last two clubs. ⚽️

Chelsea FC: Finally fulfilling its God-given role as a feeder club for American soccer managers. ⚽️

Oh cool, it’s Emo Dorothy Sayers.

Via Ethan Iverson, Vinnie Sperrazza gives us the backbeats.

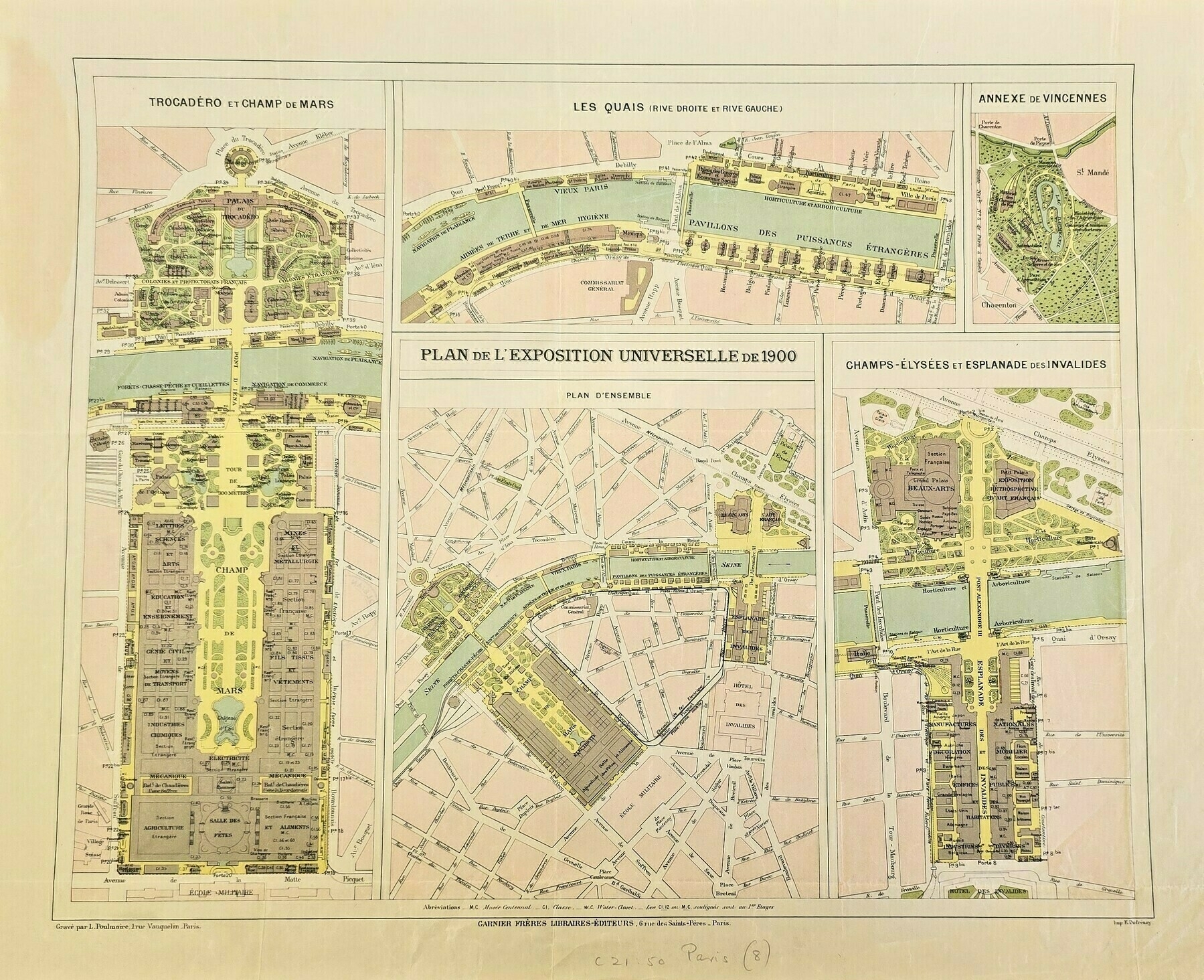

Plan de l’exposition universelle de 1900. Full-size image here.

just before I lost that finger

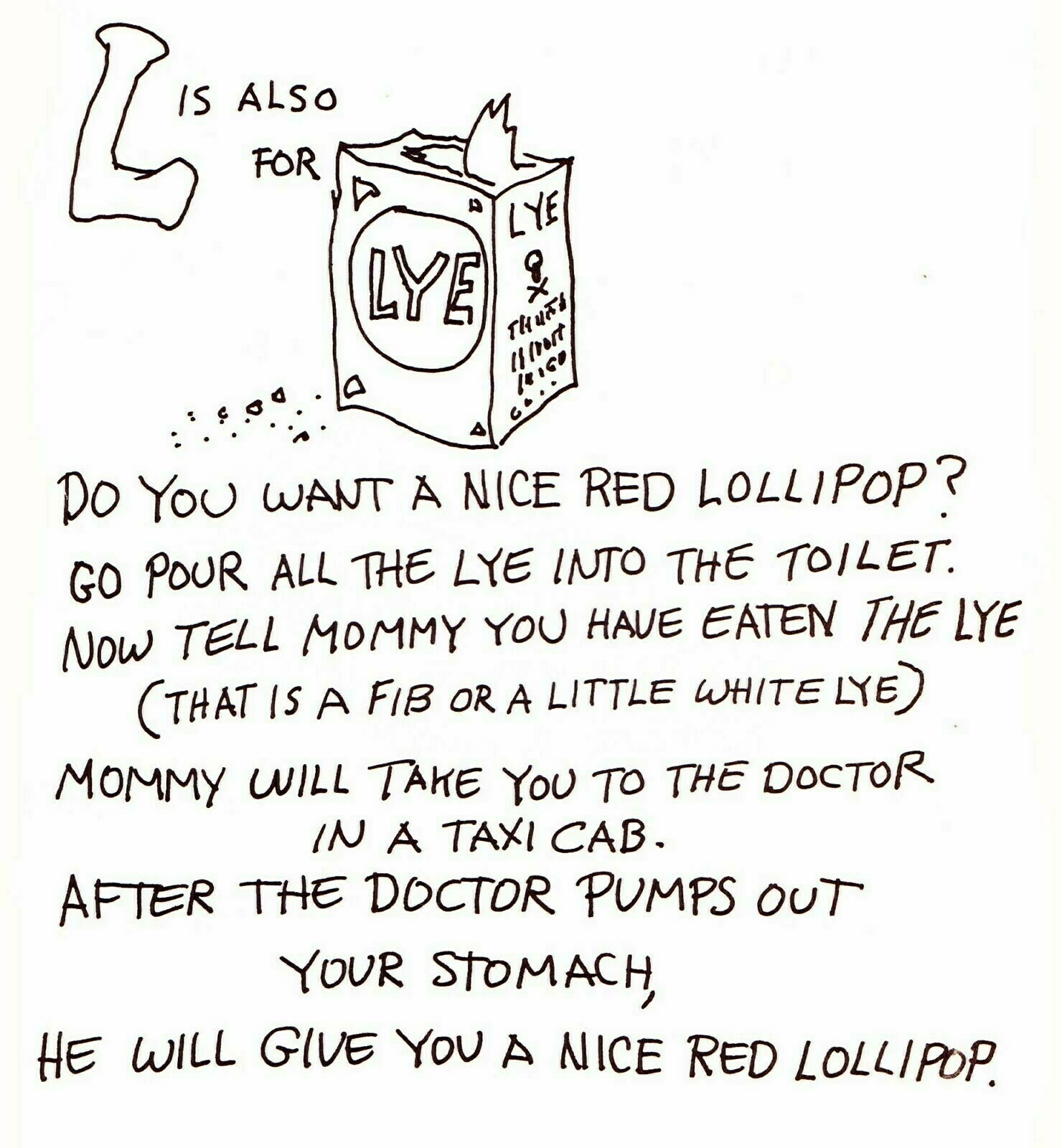

This article on the essential Shel Slverstein omits what I believe to be his masterpiece: Uncle Shelby’s ABZ Book.

I wrote about something I call the diaconal charism.