I deleted my big-blog post on today’s big SCOTUS ruling. I think I have a useful point, but today’s not the time to make it. People will be too heated. I’ll save the post and publish it in 2034.

Just a gentle reminder of a point I’ve often made: if you read the actual text of Supreme Court opinions instead of journalists' descriptions of them, you’ll see (a) the existing law which the court is interpreting, and is legally bound to respect; (b) the relevant precedents which they’re professionally bound to reckon with; (c) the reasoning — complete with clarifications, distinctions, and the setting of boundaries — which both majority and dissent employ to reach their decisions; and (d) the diversity of opinion even among justices who are on the same side of the question. You can’t fairly judge a decision simply on the basis of whether or not you like the outcome’s implications for the present moment.

“What lies have I ever told? There is no need for lying, seeing that mankind are such fools … tell them the truth and they will mislead themselves by their own vanities and save me the trouble of invention.” — Mephistopheles, in Dorothy L. Sayers’s The Devil to Pay

“Wonderful is the effect of impudent and persevering lying.” — Thomas Jefferson, letter from Paris to William Stephens Smith, 13 November 1787

supple and athletic minds

Walt Whitman, Democratic Vistas (1871):

A new theory of literary composition for imaginative works of the very first class, and especially for highest poems, is the sole course open to these States. Books are to be call’d for, and supplied, on the assumption that the process of reading is not a half sleep, but, in highest sense, an exercise, a gymnast’s struggle; that the reader is to do something for himself, must be on the alert, must himself or herself construct indeed the poem, argument, history, metaphysical essay — the text furnishing the hints, the clue, the start or frame-work. Not the book needs so much to be the complete thing, but the reader of the book does. That were to make a nation of supple and athletic minds, well-train’d, intuitive, used to depend on themselves, and not on a few coteries of writers.

A recommendation more important now than ever.

Sometimes I think that the best writing set-up I ever had was 30 years ago when I had a PowerBook 100, wrote in Word 5.1, and kept my notes and ideas in HyperCard.

Will Republicans Save the Humanities?

Jenna Silber Storey and Benjamin Storey:

At public colleges in red and purple states like Arizona, Florida, Mississippi, North Carolina, Ohio, Tennessee, Texas, and Utah, about 200 tenure- and career-track faculty lines are being created in new academic units devoted to civic education, according to Paul Carrese, founding director of the School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership (SCETL) at Arizona State University. These positions are being filled by faculty members trained in areas including political theory, history, philosophy, classics, and English. Since there are only about 2,000 jobs advertised in all those disciplines combined in a typical year, the creation of 200 new lines is a significant event. […]

Criticism of these new programs is both understandable and premature. Most of them have just been founded and have yet to demonstrate exactly how they intend to fulfill the mandates that have set them in motion. They have not had time to create a track record by which they might be judged, and they will each develop in different ways. For now, understanding the motivations of the faculty members who join them may be the best way to discern where those programs are headed. Who are the academics working in these programs? Why have they moved from other colleges? How do they think about their responsibility to the legislative mandates that created these projects? And how do they plan to build academic programs with integrity under intense and conflicting political pressures, from both on and off campus?

A sharp and fair-minded report. I would add that almost all of these endeavors are rooted not in conservatism but in classical liberalism — which is how they attract non-conservatives. This is not a MAGA project but an Enlightenment project, especially the Enlightenment of Washington, Jefferson, and Madison. (Thus the centrality of political philosophy — literature and the other arts just come along for the ride, but they seem to be welcome.)

I especially appreciate this paragraph from late in the piece:

The final challenge these schools face, in our view, is to articulate their programs as a renaissance rather than a reaction. Many of the faculty members moving to these schools bring with them powerful memories of elements of their own academic training that are underappreciated: great books programs at the University of Chicago and Columbia University, courses in grand strategy at Yale University, curricula that focus on the American founding or British constitutionalism. To be part of a renaissance that endures, efforts to revive neglected subfields and forgotten courses must resist the temptation of nostalgia for a lost golden age. The Renaissance we remember did not simply revel in old texts of Cicero, it gave birth to novel forms of art and thought that focused on the distinct challenges of its moment.

I’ve seen a number of comments from LPC* academics about these new programs, and their view, unsurprisingly, seems to be that they’d rather see the humanities destroyed altogether than see such programs succeed. I get it; it’s hard, when one has wielded unchallenged power for so long, to deal with resistance.

Philip Jenkins, who recently wrote so kindly about The Shield of Achilles, has noted how cursory is the English Wikipedia page for Auden’s great poetic sequence the “Horae Canonicae” — in dramatic contrast to the extraordinary Swedish Wikipedia page. Perhaps I should move to Sweden….

Just sent this to my friend Adam Roberts.

Harsh, but not wrong

The great baptismal font at the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta in Siena has been restored.

My colleague Philip Jenkins has written a lovely commendation of my edition of Auden’s The Shield of Achilles, with a particular emphasis on the “Horae Canonicae.”

Experimenting with B&W film (llford HP5 Plus 400).

Finished reading: Charmed Lives by Michael Korda. One of the most remarkable memoirs I’ve ever read, full of amazing stories. The ones about (a) Orson Welles and (b) a decrepit member of the Rothschild family are worth the price of admission by themselves. 📚

Another Trollope post: the counterpart to Lady Arabella.

counterparts

More Trollopean spoilers here.

One of Trollope’s more interesting habits as a novelist is the tendency to create counterparts: a character in one novel will mirror a character in another. The proper counterpart of Lady Arabella in Doctor Thorne, whom I discussed in my previous post, appears in the next Barsetshire novel, Framley Parsonage: I refer to Lady Lufton. Like Lady Arabella, Lady Lufton is a woman of high rank who treasures that rank, and a woman with one son who treasures that son and desperately wants him to marry appropriately.

But whereas Lady Arabella is fretful and nervous, Lady Lufton is a masterful woman. Her circumstances are different: she is a widow and must make her own decisions; and far from being financially embarrassed she is quite rich. Moreover, she is exceptionally generous with her wealth. Mark Robarts, a clergyman who is a recipient of her patronage, thinks of her thus:

He knew a good deal respecting Lady Lufton’s income and the manner in which it was spent. It was very handsome for a single lady, but then she lived in a free and open-handed style; her charities were noble; there was no reason why she should save money, and her annual income was usually spent within the year. Mark knew this, and he knew also that nothing short of an impossibility to maintain them would induce her to lessen her charities. She had now given away a portion of her principal to save the property of her son — her son, who was so much more opulent than herself, — upon whose means, too, the world made fewer effectual claims.

But Lady Lufton’s habit of generosity has this effect on her: it makes her more accustomed to getting her way. She does not give with conditions, but she expects her generosity to be properly acknowledged. She loves Mark Robarts, who has been her son Lord Lufton’s closest friend since childhood; but she expects that a mere country vicar, the son of a provincial doctor, and his wife Fanny will know better than to think that his sister Lucy could be a proper mate for her son. Mark and Fanny do nothing to promote the match; but they don’t send Lucy away either.

Lucy herself is mindful that she is far below Lord Lufton on the social scale, and, though she loves him, refuses his proposal of marriage; then, when he renews it, she tells him that she will only marry him if his mother explicitly endorses the marriage. When Lufton presses his mother to accept Lucy, she is in agony. She knows that her son loves Lucy, but all along she has hoped for him to marry the stately and elegant Griselda Grantly (daughter of Archdeacon Grantly, whom we came to know back in Barchester Towers).

When pressed to explain her disapproval of Lucy, Lady Lufton feels that she can’t risk being too blunt. (“But her father was a doctor of medicine, she is the sister of the parish clergyman, she is only five feet two in height, and is so uncommonly brown! Had Lady Lufton dared to give a catalogue of her objections, such would have been its extent and nature. But she did not dare to do this.”) So she equivocates:

And then at last Lady Lufton spoke it out. “She is — insignificant. I believe her to be a very good girl, but she is not qualified to fill the high position to which you would exalt her.”

“Insignificant!”

“Yes, Ludovic, I think so.”

“Then, mother, you do not know her. You must permit me to say that you are talking of a girl whom you do not know. Of all the epithets of opprobrium which the English language could give you, that would be nearly the last which she would deserve.”

“I have not intended any opprobrium.”

“Insignificant!”

“Perhaps you do not quite understand me, Ludovic.”

“I know what insignificant means, mother.”

“I think that she would not worthily fill the position which your wife should take in the world.”

“I understand what you say.”

“She would not do you honour at the head of your table.”

Lady Lufton’s objections are largely pictorial — they involve her sense that the grace and stature and elegance of the Lufton family must be visually manifested in the next Lady Lufton, a personage so “exalted.” And these objections loom large in her mind; but, it turns out, not as large as her genuine love for her son, and her desire that he be happy.

After much soul-searching and inward struggle, Lady Lufton visits Lucy Robarts — who has in the meantime (and Lady Lufton has noticed this) devoted herself to charity not through money but through self-sacrificial generosity, at some risk to her own health — to put a question to her:

“He is the best of sons, and the best of men, and I am sure that he will be the best of husbands.”

Lucy had an idea, by instinct, however, rather than by sight, that Lady Lufton’s eyes were full of tears as she spoke. As for herself she was altogether blinded and did not dare to lift her face or to turn her head. As for the utterance of any sound, that was quite out of the question.

“And now I have come here, Lucy, to ask you to be his wife.”

Trollope can be fierce, as I noted in my previous post, but he can also be sweet, and one of the sweetest moments in all his voluminous works comes in Lady Lufton’s final words, in this scene, to Lucy, when they agree on a time for Lucy to return to Framley Court:

“Well, dearest, you shall be quiet; the day after to-morrow then. — Mind we must not spare you any longer, because it will be right that you should be at home now. He would think it very hard if you were to be so near, and he was not to be allowed to look at you. And there will be some one else who will want to see you. I shall want to have you very near to me, for I shall be wretched, Lucy, if I cannot teach you to love me.”

Here Lady Lufton has wholly humbled herself: she is no longer “stern and cross, vexatious and disagreeable,” demanding and censorious. She does not insist on her status, but casts it aside and woos Lucy. “I shall be wretched, Lucy, if I cannot teach you to love me.” Her desire to love and be loved proves stronger than her image of Lufton greatness.

Needless to say, Lady Arabella Gresham would be capable of none of this: not the self-critique, not even a moment of self-reflection; not the weighing of the claims of rank against the claims of happiness. Lady Arabella is by birth a de Courcy, and one of the regular themes of the Barsetshire novels is the sheer rapacity of the de Courcys. In the next novel in the series, The Small House at Allington, we see them ceaselessly working to consolidate their status, like a mafia clan. (The Countess de Courcy is like a British female equivalent to the mature Michael Corleone, only less decent.) They represent the British class system at its worst; in Lady Lufton we see — it is a rare enough thing in Trollope — a path to moral redemption for the rich and lofty.

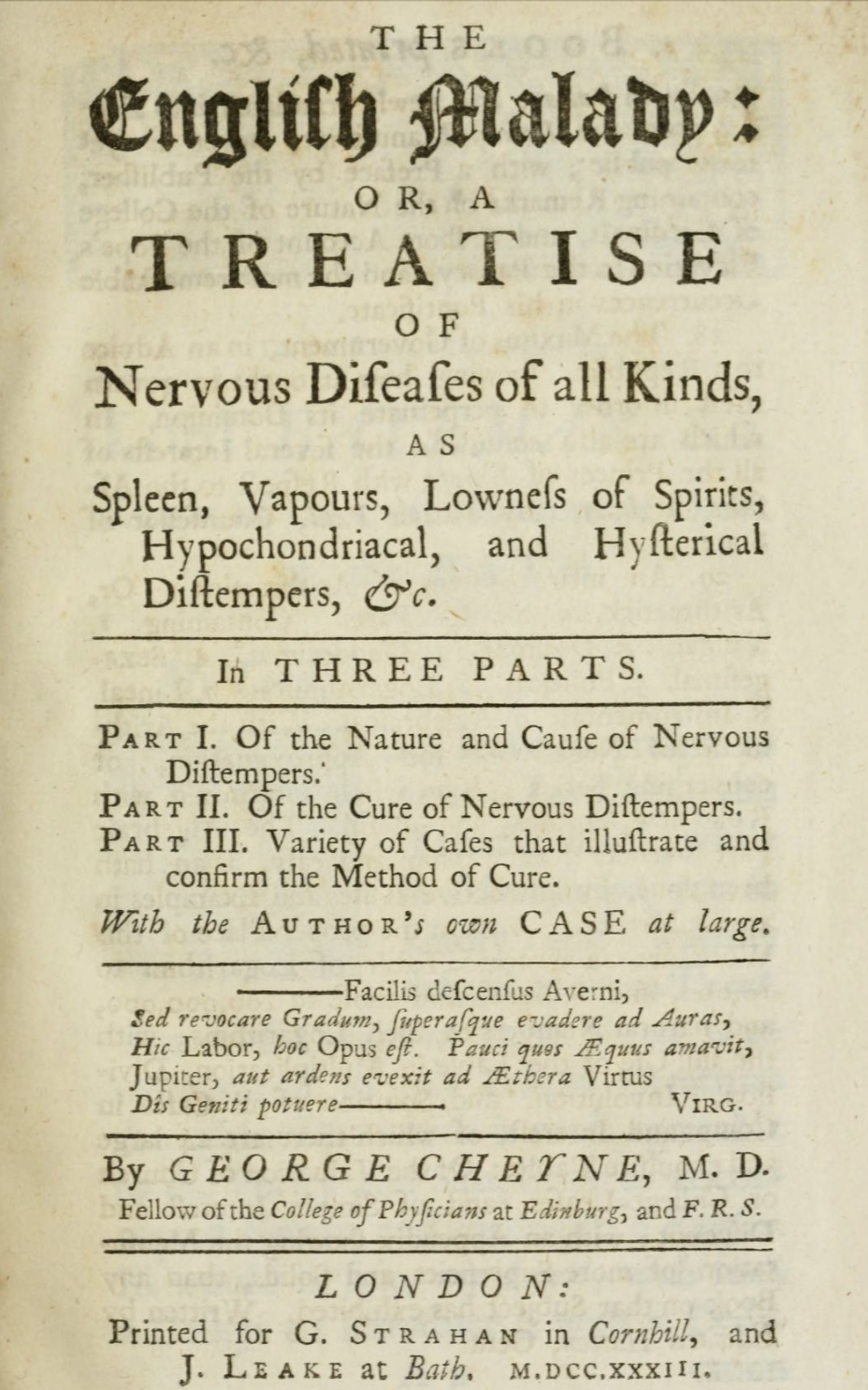

“The Title I have chosen for this Treatise, is a Reproach universally thrown on this Island by Foreigners, and all our Neighbours on the Continent, by whom Nervous Distempers, Spleen, Vapours, and Lowness of Spirits, are, in Derision, call’d the ENGLISH MALADY. And I wish there were not so good grounds for this Reflection. The Moisture of our Air, the Variableness of our Weather, (from our Situation amidst the Ocean) the Rankness and Fertility of our Soil, the Richness and Heaviness of our Food, the Wealth and Abundance of the Inhabitants (from their universal Trade), the Inactivity and sedentary Occupations of the better Sort (among whom this Evil mostly rages) and the Humour of living in great, populous, and consequently unhealthy Towns, have brought forth a Class and Set of Distempers, with atrocious and frightful Symptoms, scarce known to our Ancestors, and never rising to such fatal Heights, nor afflicting such Numbers in any other known Nation. These nervous Disorders being computed to make almost one third of the Complaints of the People of Condition in England.”

After watching Ukraine-Belgium, I’m thinking that the malaise afflcting England — the English players look and sound genuinely disconsolate that they didn’t get knocked out — is spreading to the rest of the tournament. It used to be said that melancholy is “the English malady” — true once more! ⚽️