money is magic

Spoilers ahead, but come on, you know how books like this end.

Trollope’s Doctor Thorne is the classic story about the poor orphan girl who turns out to be a princess, but with a twist: Trollope asks how a poor orphan girl can become a princess, and his answer is: With money. Mary Thorne doesn’t have a fairy godmother; but she has an unexpected inheritance. That is to say: money is magic. Money is indeed the most powerful magic imaginable, at least in some circumstances, and all of the major characters in Doctor Thorne know it, and indeed talk about it openly.Look for instance at this extraordinarily blunt conversation between Frank Gresham and his father. Frank is pressing his father to explain why, if he thinks Mary’s illegitimate birth so terrible, he allowed Mary to associate with his own children. At first Mr. Gresham is somewhat evasive:

“It is a misfortune, Frank; a very great misfortune. It will not do for you and me to ignore birth; too much of the value of one’s position depends upon it.”(Mr Moffatt is a rich man without birth whom the Greshams eagerly sought as a husband for their eldest daughter Augusta; and Frank’s mother and aunt had flatly ordered him to woo Miss Dunstable — one of Trollope’s finest creations, incidentally —, the heiress to a fortune her father acquired through inventing and selling a patent medicine.)“But what was Mr Moffat’s birth?” said Frank, almost with scorn; “or what Miss Dunstable’s?” he would have added, had it not been that his father had not been concerned in that sin of wedding him to the oil of Lebanon.

“True, Frank. But yet, what you would mean to say is not true. We must take the world as we find it. Were you to marry a rich heiress, were her birth even as low as that of poor Mary —“Mr. Gresham is simply pointing out to his son that birth and money alike are means of exchange — tradable in the social marketplace. (The social marketplace, in which people bargain and buy and sell to raise their position, is what Mr. Gresham means by “the world.”) That one must do one’s best in that marketplace is a given for all of the Greshams except Frank. Mr. Gresham is the only member of his family who in any way questions this view of things, the only one who, as can be seen in the quotation above, understands Frank’s love for Mary; but he will not rock that boat, even though he knows that he and his wife are wholly responsible for Frank’s financial difficulties. He expects Frank to blame him for his fiscal imprudence, perhaps even to hate him for making marriage with Mary impossible; but he also expects that Frank will acknowledge and obey the cold logic of the marketplace. “We must take the world as we find it.”“Don’t call her poor Mary, father; she is not poor. My wife will have a right to take rank in the world, however she was born.”

“Well, — poor in that way. But were she an heiress, the world would forgive her birth on account of her wealth.”

“The world is very complaisant, sir.”

“You must take it as you find it, Frank. I only say that such is the fact. If Porlock [a cousin] were to marry the daughter of a shoeblack, without a farthing, he would make a mésalliance; but if the daughter of the shoeblack had half a million of money, nobody would dream of saying so. I am stating no opinion of my own: I am only giving you the world’s opinion.”

“I don’t give a straw for the world.”

“That is a mistake, my boy; you do care for it, and would be very foolish if you did not. What you mean is, that, on this particular point, you value your love more than the world’s opinion.”

Similarly, Frank’s sister Beatrice, Mary Thorne’s most intimate friend, thinks it obviously impossible that Mary should marry Frank and is disconcerted to discover that Mary does not necessarily agree.

The great ogress in this story — or, the wicked witch who stands in the way of the hidden princess — is Frank’s mother, Lady Arabella, and she is truly horrible. But late in the book, when she is making one more attempt to dissuade her son from pursuing Mary Thorne, Trollope pauses in his narration to say this:

Before we go on we must say one word further as to Lady Arabella’s character. It will probably be said that she was a consummate hypocrite; but at the present moment she was not hypocritical. She did love her son; was anxious — very, very anxious for him; was proud of him, and almost admired the very obstinacy which so vexed her to her inmost soul. No grief would be to her so great as that of seeing him sink below what she conceived to be his position. She was as genuinely motherly, in wishing that he should marry money, as another woman might be in wishing to see her son a bishop; or as the Spartan matron, who preferred that her offspring should return on his shield, to hearing that he had come back whole in limb but tainted in honour. When Frank spoke of a profession, she instantly thought of what Lord de Courcy might do for him. If he would not marry money, he might, at any rate, be an attaché at an embassy. A profession — hard work, as a doctor, or as an engineer — would, according to her ideas, degrade him; cause him to sink below his proper position; but to dangle at a foreign court, to make small talk at the evening parties of a lady ambassadress, and occasionally, perhaps, to write demi-official notes containing demi-official tittle-tattle; this would be in proper accordance with the high honour of a Gresham of Greshamsbury. We may not admire the direction taken by Lady Arabella’s energy on behalf of her son, but that energy was not hypocritical.Her position, and the “energy” with which she defends it, are not hypocritical because neither she nor any other member of her family pretends to think in any other way. Their vice pays no tribute to any virtue. When dissuading Frank from pursuing Mary, they could have found a thousand ways to camouflage their greed, to disguise it as something else altogether, but they never bother to do so. They simply say, in precisely these words, “Frank, you must marry money.” And when Lady Arabella says to Mary that Frank is regrettably pledging himself to “you who have nothing to give in return,” she doesn’t even think she is insulting Mary: she is merely describing the plain facts of the case, for Mary has neither family nor rank nor money — she has no currency.

Trollope’s forthrightness on these points is rarely matched in novelists; one of his few peers in this regard is his great predecessor Jane Austen. As Auden writes in his “Letter to Lord Byron,”

You could not shock her more than she shocks me; Beside her Joyce seems innocent as grass. It makes me most uncomfortable to see An English spinster of the middle-class Describe the amorous effects of ‘brass’, Reveal so frankly and with such sobriety The economic basis of society.Ditto with Trollope. And both writers disguise with brightness of tone the fierceness of their condemnation.

But Trollope bites deeper than Austen does, at least in this novel. The scene in Doctor Thorne in which Lady Arabella tries to compel Mary to renounce Frank is closely modeled on the scene in Pride and Prejudice in which Lady Catherine tries to compel Elizabeth Bennett to renounce Mr. Darcy. Neither attempt works; in each case the socially inferior younger woman proves capable of resisting the demands of the socially superior older one. But Elizabeth benefits from no unexpected inheritance; in the end she is accepted simply because Mr. Darcy need please no one, and his enormous wealth ensures that everyone will want to please him. (Elizabeth’s father slyly notes this.) And her path is smoothed, to some extent anyway, by the social currency she does have: as she says to Lady Catherine about Mr. Darcy, “He is a gentleman; I am a gentleman’s daughter; so far we are equal.”

In Doctor Thorne, by contrast, we enjoy the spectacle of an entire family who had found the bastard Mary Thorne unthinkable as a mate for Frank welcome her with hosannas as soon as she acquires a shitload of cash; not one of them learns a damned thing or changes in any way — indeed, if anything they are confirmed in the rightness of their views of the world, because in the end they get precisely what they want. And Trollope makes no comment on this at all; he reports, we decide.

VAR check in the Brazil- Costa Rica match is taking so long that I’ve just turned the match off. The people who run footy are just killing the game. ⚽️

Cloud.

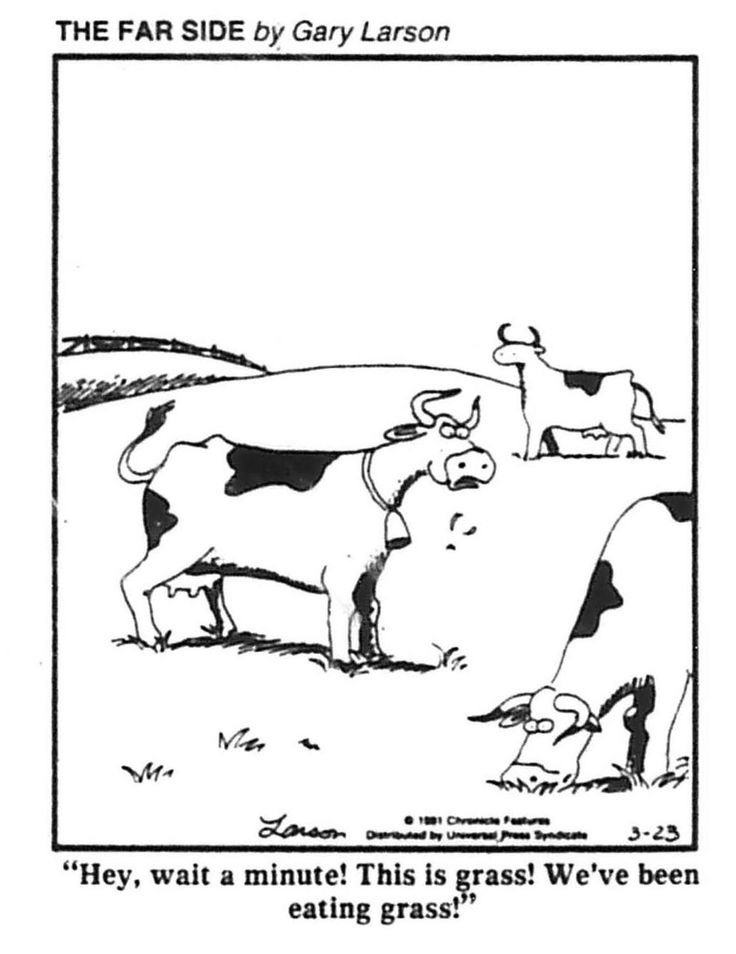

I wrote about waiting for people to realize that they’re just eating grass.

when you're ready to stop eating grass

This is a kind of follow-up to my previous post, in which I described this blog as a venue for conserving and transmitting what I believe to be valuable and worthy of our attention. But I don’t want to argue with people about how they spend their time and what they devote their attention to. Now, sometimes I forget this principle and end up arguing anyway. But why would I even try to avoid it?

In 1940 C. S. Lewis gave a talk, later to be published as an essay, called “Why I Am Not a Pacifist.” Lewis begins this talk by discussing conscience, which makes sense, since pacifists often account for their position by appealing to their conscience. Their conscience tells them that fighting in a war is wrong. But to say merely this is to obscure a question that Lewis thinks important: How does one arrive at moral judgments, e.g. the judgment that fighting in a war is wrong? Lewis addresses this question by saying that arriving at judgments about right and wrong is functionally or structurally similar to arriving at judgments about truth and falsehood. So how do we do that?

Lewis says that there are three elements to “any concrete train of reasoning”:

Firstly, there is the reception of facts to reason about. These facts are received either from our own senses, or from the report of other minds; that is, either experience or authority supplies us with our material. But each man's experience is so limited that the second source is the more usual; of every hundred facts upon which to reason, ninety-nine depend on authority. Secondly, there is the direct, simple act of the mind perceiving self-evident truth, as when we see that if A and B both equal C, then they equal each other. This act I call intuition. Thirdly, there is an art or skill of arranging the facts so as to yield a series of such intuitions which linked together produce a proof of the truth or falsehood of the proposition we are considering.

Lewis is especially interested in the second step, intuition. (By the way, it is not just Lewis who uses the term in this way: he’s borrowing from Thomas Aquinas.) And one point he makes about intuition is especially important:

The second, the intuitional element, cannot be corrected if it is wrong, nor supplied if it is lacking. You can give the man new facts. You can invent a simpler proof, that is, a simpler concatenation of intuitable truths. But when you come to an absolute inability to see any one of the self-evident steps out of which the proof is built, then you can do nothing. No doubt this absolute inability is much rarer than we suppose. Every teacher knows that people are constantly protesting that they “can't see” some self-evident inference, but the supposed inability is usually a refusal to see, resulting either from some passion which wants not to see the truth in question or else from sloth which does not want to think at all. But when the inability is real, argument is at an end. You cannot produce rational intuition by argument, because argument depends upon rational intuition. Proof rests upon the unprovable which has to be just “seen.” Hence faulty intuition is incorrigible. It does not follow that it cannot be trained by practice in attention and in the mortification of disturbing passions, or corrupted by the opposite habits. But it is not amenable to correction by argument.

And as with rational intuition, so also with moral intuition. If you simply cannot see that, for instance, eating people is wrong, then no one will be able to come up with an argument to convince you. Your mind may be alterable, but not by that means.

Think about the hundreds of millions of people who spend their days shitposting; dragging political enemies on social media; writing to complete strangers to tell them that they’re stupid or evil; scrolling through TikTok for endless hours — I can’t find the link now, but one person recently reported noticing that the person sitting just in front of her on a 10-hour transoceanic flight never stopped watching TikTok for the duration —; drooling enviously over perfect Instagram lives; constantly self-diagnosing their own manifold mental illnesses; constantly pursuing their porn preferences into darker and darker places … a properly functioning intuitive faculty would tell them that all this is an absolutely shitty way to live … but their intuitive faculty is broken, or has never been developed.

You just have to wait for the moment when they realize that all this time they’ve been eating grass. And then, when that happens, you need to have something better, something that’s tastier and more nutritious, waiting for them.

what love wants to say

Cheryl Mendelson is a philosopher, a lawyer, a novelist, and the author of a legendary book about housekeeping. (We’ve been using our copy for a quarter-century now.) And her new book, Vows: The Modern Genius of an Ancient Rite, stands somehow at the intersection of all those things. After all, a wedding ceremony, with vows at its center, is a peculiar rite indeed. To make such a vow is to promise; is to enter into a kind of contract; is the fruit of a decision for two people to make a home together. And of course, the events that lead up to a marriage, the events that constitute a marriage, and (sometimes) the events that end a marriage, are endlessly productive of stories. This is all to say that Cheryl Mendelson is probably the perfect person to write this book.

(Disclosure: I don’t know Cheryl Mendelson but have known her husband Edward for many years now. He is W. H. Auden’s literary executor and has always been of inestimable aid and support to my work on Auden.)

Mendelson begins the book by describing her first marriage, one made impulsively when she was quite young; she concludes by describing her happily enduring second marriage. And it is her belief that we can grasp why one marriage failed and the other succeeded by understanding how the couples felt about, how they thought about, how they understood (or failed to understand) the vows with which they began their lives together. It’s a brilliant notion and one that frames the whole narrative, which is largely historical but also sociological, psychological, moral — and (often) religious, since the wedding vows we all know arose through the long development of Christian rites of Holy Matrimony.

After describing her hasty first marriage, Mendelson writes,

It's hard to imagine a world in which our absurd decision to marry wouldn't have ended in divorce. But I could see that friends whose marriages had more propitious beginnings than ours had to fight many of the same battles. The general atmosphere of suspicion toward the institution seemed to me to seep into actual marriages, exaggerating their frustrations and minimizing their satisfactions. Most marriages in our circle of friends broke up. Social hostility toward marriage and even toward love, expressed in contempt, disapproval, and unfriendly theorizing, took a toll on both.

This widespread social hostility to, or at best irony about, marriage is, it seems to me, the primary impetus for the book. Mendelson challenges it, and challenges it compassionately but forcefully. She knows that her celebration of marriage (and its classic vows) will be a hard sell for many:

To write about the marriage vows … is to pick one’s way through a cultural minefield. Whether wedding vows need rethinking, updating, or, possibly, discarding is now a wide-open question. Having thought, read, and rethought, I concluded – for reasons that this book exists to lay out – that the answer is a solid no. The traditional marriage vows, though they contain phrases composed a thousand or more years ago, are a form of words that say exactly what love still wants to say.

Vows is a remarkable book, and I hope it gets a wide readership. The defense and, more, celebration of fidelity (Chapter 9) is itself worth the price of admission, and I wonder how many readers will reckon seriously with the case Mendelson makes. More generally, I would be especially interested to hear how people who despise marriage reckon with the book’s arguments. They won’t find Mendelson easy to refute.

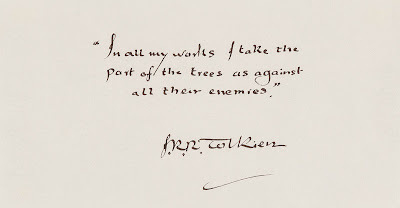

Recently bought at auction [CLARIFICATION: But not by me!]

Fascinating: in China, bookstore book placement as political protest.

unconditional love

I sat across from the missionary, pretending to drink a beer. I was new to beer, and it still tasted bad to me, the way it tastes to children. The second-floor boy was there, too, our shoulders touching. The missionary was talking about love again. The most important thing about God, he told us, was that he loved you unconditionally. For some reason, this startled me. It almost angered me. Who, I asked the missionary, taking a fake sip from the beer bottle, would actually want to be loved like that? All-encompassing, all-permitting love sounded indiscriminate. And what were we doing here — at our fancy school, in our charmed lives — if not learning to discriminate, to value things in and for their particulars?

“All-encompassing” and “all-permitting” are not synonyms. God doesn’t permit everything; God doesn’t approve everything; God’s discriminations are infinitely subtler than ours. He sees all your sins and names them as sins; he sees all your errors and names them as errors. He is ruthless in His exposure of your deceptions of others and your self-deceptions. He doesn’t miss anything, and he doesn’t think your poems are as good as Keats’s, or your essays as good as Joan Didion’s, unless your poems and essays actually are that good. But he loves you anyway, all the time, and all the way — just as much as He loves that person down the street, that dimwit, that asshole, that person you never want to see again. The love of God shines on the excellent and the assholes alike.

The Good News here is that if you ever stop being excellent and start becoming a dimwit or an asshole or both at once, God will see it, he will know it, he will know it better than you do, he won’t call it anything except what it is … but he will love you just as much as he did when you were excellent. Because Love doesn’t keep score.

I said grace cannot prevail until law is dead, until moralizing is out of the game. The precise phrase should be, until our fatal love affair with the law is over — until, finally and for good, our lifelong certainty that someone is keeping score has run out of steam and collapsed. As long as we leave, in our dramatizations of grace, one single hope of a moral reckoning, one possible recourse to salvation by bookkeeping, our freedom-dreading hearts will clutch it to themselves. And even if we leave none at all, we will grub for ethics that are not there rather than face the liberty to which grace calls us. Give us the parable of the Prodigal Son, for example, and we will promptly lose its point by preaching ourselves sermons on Worthy and Unworthy Confession, or on The Sin of the Elder Brother. Give us the Workers in the Vineyard, and we will concoct spurious lessons on The Duty of Contentment or The Moral Aspects of Labor Relations.

Restore to us, Preacher, the comfort of merit and demerit. Prove for us that there is at least something we can do, that we are still, at whatever dim recess of our nature, the masters of our relationships. Tell us, Prophet, that in spite of all our nights of losing, there will yet be one redeeming card of our very own to fill the inside straight we have so long and so earnestly tried to draw to. But do not preach us grace. It will not do to split the pot evenly at four A.M. and break out the Chivas Regal. We insist on being reckoned with. Give us something, anything; but spare us the indignity of this indiscriminate acceptance.

I am interested in the Texas v. New Mexico case because I am fascinated by the perennial shortage of water in the West and horrified by our persistent refusal to face the facts. I wrote an essay last year, for Raritan, on how that crisis looks from this side of the 100th meridian: here it is.

IANAL, but I am fascinated by legal arguments, and will sometimes read and annotate SCOTUS opinions, for instance, Texas v. New Mexico. N.B.: That has no intellectual value, it’s just one of the weird things I do. Any lawyer will see how little I know.

A stop-motion animation version of Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi? Yes, please. Please, please, PLEASE.

I wrote about how to be a non-infantile observer of the Supreme Court.

a numbers game

The Supreme Court of the United States has been busy this week (notes this SCOTUS-watcher, whose pinned tabs include supremecourt.gov). You hear a lot these days about a “polarized” and therefore somehow illegitimate court. A 6-3 court, we always hear, with six Republican appointees (Chief Justice Roberts, Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, Barrett) and three Democratic appointees (Kagan, Sotomayor, Jackson). The Court has handed down nine opinions in the past two days. Let’s break down the votes, using the bold/italic formatting used above to make things clear:

JACKSON, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which ROBERTS, C. J., and SOTOMAYOR, KAGAN, and KAVANAUGH, JJ., joined. GORSUCH, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which THOMAS, ALITO, and BARRETT, JJ., joined.

BARRETT, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which ROBERTS, C. J., and THOMAS, ALITO, and KAVANAUGH, JJ., joined. GORSUCH, J., filed an opinion concurring in the judgment. SOTOMAYOR, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which KAGAN and JACKSON, JJ., joined.

GORSUCH, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which ROBERTS, C. J., and THOMAS, SOTOMAYOR, KAGAN, and BARRETT, JJ., joined. ROBERTS, C. J., and THOMAS, J., filed concurring opinions. KAVANAUGH, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which ALITO, J., joined, and in which JACKSON, J., joined except as to Part III. JACKSON, J., filed a dissenting opinion.

KAGAN, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which SOTOMAYOR, KAVANAUGH, BARRETT, and JACKSON, JJ., joined, and in which THOMAS and GORSUCH, JJ., joined as to Parts I, II, and IV. THOMAS, J., and GORSUCH, J., filed opinions concurring in part. ALITO, J., filed an opinion concurring in the judgment, in which ROBERTS, C. J., joined.

ROBERTS, C. J., delivered the opinion for the Court, in which ALITO, SOTOMAYOR, KAGAN, GORSUCH, KAVANAUGH, BARRETT, and JACKSON, JJ., joined. SOTOMAYOR, J., filed a concurring opinion, in which KAGAN, J., joined. GORSUCH, J., KAVANAUGH, J., BARRETT, J., and JACKSON, J., filed concurring opinions. THOMAS, J., filed a dissenting opinion.

Per curiam decision — that is, by the whole court with no one justice writing the opinion. A rare thing, done in this case for reasons too complicated to get into here.

KAVANAUGH, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which ROBERTS, C. J., and SOTOMAYOR, KAGAN, and JACKSON, JJ., joined. JACKSON, J., filed a concurring opinion. BARRETT, J., filed an opinion concurring in the judgment, in which ALITO, J., joined. THOMAS, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which GORSUCH, J., joined.

Chiaverini v. City of Napoleon:

KAGAN, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which ROBERTS, C. J., and SOTOMAYOR, KAVANAUGH, BARRETT, and JACKSON, JJ., joined. THOMAS, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which ALITO, J., joined. GORSUCH, J., filed a dissenting opinion.

This is a pretty typical set of SCOTUS decisions in one major way: only one of the decisions (Munoz) follows the 6-3 split that, we are told by almost all who write about such matters, shitposters and professionals alike, simply defines the character of the court. But as Adam Feldman has written on the invaluable Empirical SCOTUS blog, “While the justices often vote across predictable lines, less predictable individual votes often get overshadowed by decision outcomes that come down as predicted.” That is, Court observers simply ignore the decisions that don’t fit their simplistic ideological frame — it’s as though such decisions don’t happen. A decision in which the dissenters include Samuel Alito and Ketanji Brown Jackson? Unimaginable! A Court in which the supposedly all-powerful right-wingers, Thomas and Alito, are the most likely to be in the minority? Inconceivable!

Sarah Isgur co-wrote that piece I just linked to, and Advisory Opinions, the podcast she hosts with David French, is consistently very good at pointing listeners to useful articles that explore some of these nuances, and usually very good at explaining those nuances directly.* Empirical SCOTUS, as I have said, is an excellent blog, and the place to start on any given issue or case is SCOTUSblog.

If you have any interest in American law, these resources are worth exploring, because they can rescue you from the sheer infantilism that characterizes almost all commentary on SCOTUS, including most of what appears in such august venues as the New York Times. Our commentators are infantile because they have only one criterion for evaluating legal decisions on any level: Did this decision give me what I want? The law doesn’t matter to them, the facts of the cases don’t matter to them, legal reasoning is completely inaccessible to them. They just want what they want, and a judge who gives it to them is Good, and a judge who doesn’t is Bad. As I say: infantile. Don’t be that way.

* Usually but not always. I have one major beef with the podcast: both hosts, but especially Isgur, use too many pronouns. I’m always hearing “it” and asking What?? Or hearing “they” and asking Who?? Isgur and French are good friends and each can often read the other’s mind, but we listeners are not so privileged — especially those of us who are not lawyers. Similarly, sometimes they’ll say of a given case “It’s pretty obvious where this one is going” — but then they don’t say where! Or they’ll say “So this one was 7-2” without saying which way it went. I think they’re assuming that their listeners are reading the opinions, or at least reading the news, before listening to their podcast, and while sometimes that’s true for me it isn’t always. I learn a lot, but I often find myself confused as I listen, and unnecessarily so. Sarah and David just need to slow down sometimes and establish the basic facts of a given case for their audiences before going on to their analysis. Isn’t that something good lawyers always do for juries and judges?

It’s Lagerstroemia season here in central Texas.

the uncanny valley of blogging

I used to call my blog Snakes & Ladders, because that reflected my belief that culture – culture-as-a-whole – is never simply ascending or declining, but is undergoing in its various locations constant ups and downs. But beneath that point is an image of myself as an observer and critic of this cultural moment. Now I call the blog The Homebound Symphony, in honor of the Traveling Symphony in Emily St. John Mandel’s novel Station Eleven, because I have stopped thinking of myself as an observer and critic and started thinking of myself as a preserver and transmitter. Another way to put this: Whereas I once tried to be a public intellectual, I now just want to be a … I dunno, maybe a convivial conservator.

There’s no money in being a conservator, no prestige either, and almost no attention. I am dramatically less visible now than I was a decade ago, or even five years ago. But for me that’s a feature, not a bug; I have consciously worked to make my audience smaller, chiefly by focusing on what interests me, especially when it interests almost no one else. (I have my number.) That focus warms my heart and gives me peace, so I’m going to keep doing it, even if nobody notices. Looking at the whole public-intellectual game now, I think: I’m way too old for that shit.

This change of focus has also led to a renewed commitment to blogging. If you’re a public intellectual, you may need to write books and essays to make arguments, and to intervene in the Discourse via social media, to change minds. If that’s your thing, then maybe you’d want to use Substack, since it pushes its writers towards (a) hosting comments and (b) engaging with readers via the comment section and Notes. But that is soooooo not my thing; by contrast, a blog is an ideal venue for what I want to do, which is preservation and transmission. It’s a great way to put ideas and images and musical compositions in meaningful relation, including creative tension, with one another. It’s an attention cottage.

What’s funny about all this is that a blog is probably the least cool way to communicate with people. It doesn’t have old-school cred or state-of-the-art shine; it falls into a kind of uncanny valley. To be a blogger is sort of like being that Japanese guy who makes paintings with Excel. But that suits me.