New boilerplate terms & conditions for every tech company in the world: “We reserve the right to do anything we want with anything we find and for any purpose we choose, and will provide no compensation to anyone for anything under any circumstances.” That should cover it.

Ted Gioia: “When I recently revisited Rick Beato’s studio for our interview, I noted that he had added more than one million subscribers since my previous visit. That’s because music fans (like everybody else) are increasingly turning to alternative media.” Is YouTube “alternative media” though?

The Premier League loves VAR. Why don’t they care about fan frustration? Because neither attendance nor TV viewing is declining. It’s a simple story, really. ⚽️

Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist I: “So numerous indeed and so powerful are the causes which serve to give a false bias to the judgment, that we, upon many occasions, see wise and good men on the wrong as well as on the right side of questions of the first magnitude to society. This circumstance, if duly attended to, would furnish a lesson of moderation to those who are ever so much persuaded of their being in the right in any controversy. And a further reason for caution, in this respect, might be drawn from the reflection that we are not always sure that those who advocate the truth are influenced by purer principles than their antagonists.”

Currently reading: The Debate on the Constitution. Reading through these documents, so brilliantly chosen and edited by Bernard Bailyn, my two dominant thoughts are (a) Neither the Federalists nor the Antifederalists believed in the honesty or decency of their opponents, and (b) Quiet little James Madison is terrifyingly brilliant. 📚

I can never quite get over magnolias.

Charlie Stross on Microsoft Recall: “But this is an utter privacy shit-show. Victims of domestic abuse are at risk of their abuser trawling their PC for any signs that they’re looking for help. Anyone who’s fallen for a scam that gave criminals access to their PC is also completely at risk. Worse: even if you don’t use Recall, if you send an email or instant message to someone else who does then it will be OCRd and indexed via Recall: and preserved for posterity. Now imagine the shit-show when this goes corporate.”

Robin Sloan on his love for stories that give you checklists. Don’t forget to pre-order his wonderful complete-with-checklist novel Moonbound.

I’ve twice updated my post on highbrow/middlebrow/lowbrow, first with a further thought of my own, second with a correction from my friend Francis Spufford. Endless revisability is my favorite thing about blogging. Blog posts are corrigible.

Genesis: fertility

If the defining axes of Genesis 1–11 were making/naming and commanding/disobeying, those of the Patriarchal narratives are fertility/barrenness and pastoral/urban.

Over and over again the LORD promises fertility to the barren, and to the childless a multitude of descendants. The primary sign of the LORD’s covenant with the children of Abraham is circumcision, the marking of the organ of generation. But the women these circumcised men fall in love with are all beautiful but barren — barren for a long time anyway. Sarah is, famously, ninety when Isaac is born, but it’s not often noticed that Rebekah is childless for twenty years before giving birth to Esau and Jacob. (We’re not told how old Rachel was when she finally gave birth to Joseph, but internal evidence suggests that she was in her late thirties.) The line of descent of the covenant promise is perilously thin at first but then grows thicker: first one son, Isaac; then two, Esau and Jacob, though in effect only one, because Esau sells his birthright to his younger brother; then a dozen; and from that dozen, the Twelve Tribes in their multitudes.

But though this line of descent is the key one in the story that is to follow, it’s not the only one that matters. Re-reading the story this time, I was especially drawn to Chapter 21, and struck by the LORD’s great compassion for Abraham’s other family (as it were). Because Sarah was barren for so long after Hagar gave birth to Ishmael, and because Ishmael is by one reckoning Abraham’s eldest son, she despises both of them and will not even call Hagar by name, instead referring to her contemptuously as “this slavegirl.” (This will be repeated in the next generation when Rebekah will only refer to Esau’s wives Judith and Basemath as “the Hittite women.”) When she demands that Hagar be cast out of the household and into the wilderness, “the thing seemed evil in Abraham’s eyes,” but

God said to Abraham, “Let it not seem evil in your eyes on account of the lad and on account of your slavegirl. Whatever Sarah says to you, listen to her voice, for through Isaac shall your seed be acclaimed. But the slavegirl’s son, too, I will make a nation, for he is your seed.”

And when Hagar and Ishmael run out of water in the wilderness, and she sets the child aside and goes to sit “at a distance, a bowshot away” so she will not have to hear his dying cries, the LORD speaks to her (“What troubles you, Hagar?”) and consoles her with a mighty promise: “Rise, lift up the lad / and hold him by the hand, / for a great nation will I make him."

What’s fascinating about this story is how closely it mirrors the much more famous story from the next chapter, the binding of Isaac. In that second story “Abraham rose early in the morning” to take Isaac to his death; in this one “Abraham rose early in the morning” to send his son Ismael into the wilderness where he is likely to perish. In each story there is a moment of hopelessness, when death for “the lad” seems inevitable. In each story that hopelessness is banished by a sudden providence: a ram appears to take Isaac’s place, and a hitherto unseen well of water appears to rescue Ishmael and his mother. Each “lad” survives, and thrives, and inherits his promise.

In Chapter 16, which recounts the birth of Ishmael, the Lord’s messenger appears to Hagar and says,

“Look, you have conceived and will bear a son

and you will call his name Ishmael,

for the LORD has heeded your suffering.

And he will be a wild ass of a man —

his hand against all, the hand of all against him,

he will encamp in despite of all his kin."

(The ambiguity of this blessing is echoed in Chapter 27. There Esau, having had the blessing meant for him pre-empted by the deceitful Jacob, pleads for some blessing at least, and all his aged father Isaac can manage to say is “By your sword you shall live and your brother shall you serve. And when you rebel you shall break off his yoke from your neck.” These “blessings” are really prophecies of lives of struggle and conflict.)

The name Ishmael means “God has heard” — God has heard Hagar’s pleas even when Sarah would not. God does not forget her, nor her son, though he warns her that his way will be hard, and his kin will not accept him. This conflict between the children of two divine promises will continue throughout the history of the Ishmaelites, the ancestors of those whom today we call Arabs. But the descendants of Isaac and the descendants of Ishmael have one father. In Genesis 25 we are told that at his death “Abraham gave everything to Isaac” — one cannot doubt that Sarah and her child are essential to him in ways that Hagar and her child are not — but we are also told that

Isaac and Ishmael his sons buried him in the Machpelah cave in the field of Ephron son of Zohar the Hittite which faces Mamre, the field that Abraham had bought from the Hittites, there was Abraham buried, and Sarah his wife.

And what follows this burial is an account of the lineage of Isaac — and that of Ishmael. Both lineages matter because Isaac and Ishmael, and later the Israelites and Ishmaelites, are alike the children of Abraham. Whether they realize it or not, whether they accept it or not, they are bound together forever by this common lineage.

Damon Krukowski: “As a creator who requires more than zero for my content, I seem to be part of a conspiracy against Daniel Ek and Spotify. The fact of my existence challenges their program. Something has to give, in this literal zero-sum game. If I and other creators won’t accept close to zero for content, Ek and other platforms cannot operate under the conditions they require to build even a sentence. Creators must be swept aside as a conditional clause to their success.”

Ek is one of several tech leaders who have recently begun saying the quiet part aloud: he’s openly contemptuous of the people who create what he always calls “content.” And he’s rapidly moving his company to the point of paying them nothing at all. If he can’t steal their work he’ll just use AI-generated “content” — because he has contempt for his customers also.

Genesis: orientation

The story begins with creation, and creation is largely a matter of dividing: dividing the region of order from the region of chaos (tohu wabohu), then light from darkness, then the waters above from the waters below, then the waters below from the dry land, then “the lights in the vault of the heavens to divide the day from the night,” then the system of division that we call time (“the fixed times and … days and years”).

Once this creation (bara’) is complete, nothing like it ever happens again. The Lord himself does not create any more, but rather engages in yatsar – making or fashioning or fabricating, that is, working from pre-existing materials. He is now no longer a Creator but a Craftsman. He “fashions” a man from the dust of the earth, and then a woman from the rib of the man. (“The LORD God built the rib He had taken from the human into a woman.”) He also names what he has fashioned.

After fashioning and naming, he gives commands, which are disobeyed – and with that we have the elemental axes of the first eleven books of Genesis:

- making/naming

- commanding/disobeying

Almost everything that happens until the appearance of Abram can be understood in these terms. When Eve gives birth to her first son, she declares “I have got me a man with the LORD,” and Robert Alter (whose translation I am using here) points out that the verb “got” can connote “make” – like God himself, Eve may be saying, I have made a man. Cain’s name means “smith,” and so the third human being becomes the first technologist: the builder of a city (4:17) whose descendants include “the first of tent dwellers with livestock,” “the first of all who play on the lyre and pipe,” and one “who forged every tool of copper and iron”: the pastoralist, the artist, the metalworker, all people dependent on technology, though very different technologies. Makers and doers.

It is perhaps significant that this first technologist and first urbanist is also a disobeyer, indeed a murderer. (Did he use a tool to murder his brother, I wonder?) Later, in Chapter 11, when we see the massive coordinated effort to build a great Tower that reaches up to Heaven, we see perhaps the inevitable tendency of technological urbanism, as Garrison Keillor suggested many years ago in a piece on the Tower Project:

In answer to concern voiced by personnel about the future of the Super-Tall Tower project, the Company assures them that everything is fine. Also, all questions raised by Tower Critics have been taken care of: 1) While it’s true that money is needed for cancer & poverty, it will create 100,000 new jobs. 2) We’ll be able to see more from it than from any other tower. 3) With the Communist nations well along with the development of their tower, national prestige is at stake, & our confidence to meet the challenges of the future. 4) In answer to environmentalist groups, there is no viable data on which to base the whole concept of the “unbearable” hum of the elevator; anyway it would provide a warning to migrating birds. The problem of its long shadow angering the sun can be taken care of with certain sacrifices.

Re: building and making, we may – employing the strategy of division and distinction that characterized the Creation – say that the kinds are:

- What the LORD himself makes

- What He commands people to make (the Ark being the first example; there will be others)

- What he allows people to make (e.g. clothing woven from fig leaves to cover their nakedness)

- What he punishes people after the fact for making (e.g. a Super-Tall Tower)

- What he pre-emptively forbids people to make – e.g. a graven image to worship – after which he punishes them for making it anyway

In any case, these are the great themes, as I see them, of the first eleven chapters of Genesis.

I might add one more theme (one which appears in Chapter 10), a development that will fundamentally shape the Patriarchal narratives: the rise of a diversity of human cultures, including the Sea Peoples, the Babylonians, the Ninevites, Sodom and Gomorrah (the “cities of the plain”), etc. This diversity is counterbalanced by the fact that there was on the earth only one language (11.1). When that changes, then diversity forever after exceeds commonality. And thus confusion and mistrust grow.

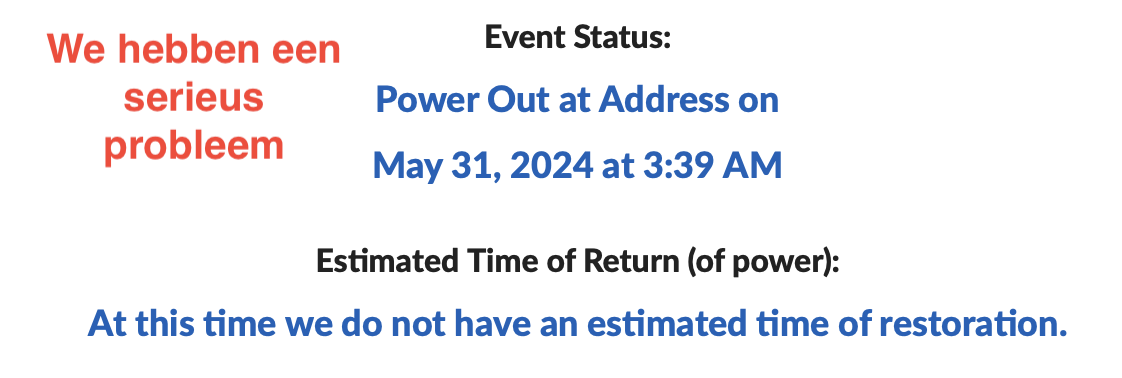

Angus, enjoying the return of the air conditioning. (As you would, were you a longhaired dog living in Texas.)

I decree this Take Your Dog To Work Day, because (a) it’s Sunday and there’s no one else around and (b) at home we’re nearing 60 hours without electricity. Air conditioning is a great thing. And Angus is enjoying the wide open spaces of the Honors Program suite.

Adam Roberts: “If a thing’s worth doing, it’s worth doing well, and that counts double if a thing was never worth doing in the first place.” This could be Adam’s career motto!