Leah Libresco Sargeant: “The struggles of much bigger tech companies to make their AI corrigible suggest Catholic Answers won’t have a reliably orthodox chatbot any time soon. But the problem with the project goes deeper: To imagine that a chatbot can be a catechist at all indicates a profound misunderstanding of how evangelization works. … God invites us to imitate him as sub-creators. It is a profound misuse of that invitation to build tools to take over our most human and relational tasks.”

St. Mark's Place

The Five Spot, on St. Mark’s Place in Manhattan, hosted most of the great jazz musicians of the middle part of the twentieth century — Charles Mingus, for instance:

It was also a block-and-a-half from 77 St. Mark’s Place, which is where for a long time Auden lived for about half of each year. (Leon Trotsky also lived there for a time, and a section of the street provided the image for the cover of Led Zeppelin’s Physical Graffiti.) I often find myself wondering how often Auden passed Miles Davis or John Coltrane on the street, or sat next to them at a local bar.

Finished reading: Holy the Firm by Annie Dillard. Teaching this today. It is, every time I read it, a dazzling and disturbing book. 📚

Finished reading: 3 Shades of Blue by James Kaplan. A brilliant book, but in its later stages immensely sad. 📚

Read this by Ted Gioia in conjunction with my everyone knows post. Twenty years from now, nobody will believe parents who say “But I had no idea that giving my five-year-old a smartphone would be harmful!” People will say, “You knew, but you didn’t care.” And they’ll be right to say it.

more rational choices

My recent posts on how I choose what fiction to read and what’s going on with the publishing industry share a theme: perverse incentives. (Indeed, it seems that a lot of my writing is about perverse incentives, but more about that another time.) The intellectual/political monoculture of the modern university leads to an intellectual/political monoculture in the major media companies, and when you combine that with the many ways the internet has disrupted the economic models of all the arts, you get a general environment in which interesting, imaginative work is not just resisted, it’s virtually prohibited. All the incentives of everyone involved are aligned against it.

Thus the thesis of this essay by James Poniewozik: “We have entered the golden age of Mid TV”:

Above all, Mid is easy. It’s not dumb easy — it shows evidence that its writers have read books. But the story beats are familiar. Plot points and themes are repeated. You don’t have to immerse yourself single-mindedly the way you might have with, say, “The Wire.” It is prestige TV that you can fold laundry to.

Or you could listen to a Sally Rooney novel on Audible while chopping the veggies. Same, basically. This is what I think about almost everything from current big-studio Hollywood movies to new literary fiction to music by Taylor Swift or Beyoncé: it’s … okay. It doesn’t offend.

But wouldn’t it be nice to have something better? Wouldn’t it be cool to be surprised? Crevecoeur famously described early America as a land characterized by “a pleasing uniformity of decent competence.” But after a while the competence isn’t all that pleasing. As Wittgenstein famously wrote in the Philosophical Investigations: “We have got onto slippery ice where there is no friction and so in a certain sense the conditions are ideal, but also, just because of that, we are unable to walk. We want to walk so we need friction. Back to the rough ground!” I wrote an essay about this.

Of course I think about this stuff all the time.

The good news is that these production-line periods tend to produce a reaction: Romantic poetry was one such; punk rock another; the Nouvelle Vague in French movies yet another. Indeed, so was Wittgenstein’s philosophy. But the bad news is that today our manorial technocracy makes the project of finding cracks in the walls more difficult than it has ever been. So I’ll be watching the rough ground to see who turns up there, but in the meantime, here’s how I make my decisions about watching movies:

- If someone I love wants me to go to a movie with them, I do.

- Otherwise, I don’t watch movies produced and/or distributed by the big studios. (I had been leaning in this direction for a while, but I didn’t make it a guideline until three or four years ago.) I just don’t, for the same reason that I don’t read novels by people who live in Brooklyn: it’s not a good bet. The chance of encountering something excellent, or even interestingly flawed, is too remote. Not impossible — I really enjoyed Dune, for instance, and Oppenheimer, both of which I watched with my son — but remote.

- I don’t subscribe to Netflix, or HBO, or Amazon Prime. (I do have Apple TV as part of my Apple subscription, but I primarily use it to rent movies. I did try watching For All Mankind and Masters of the Air, but both of them were too … Mid for me.) The only service I subscribe to is the Criterion Channel, because it allows me to watch (a) classic movies, (b) independent movies, and (c) foreign movies. All of which are much better bets than anything the current big studios make.

- I never hesitate to watch a favorite movie again when that’s where my whim takes me. In fact, I watch movies from my Blu-Ray/DVD collection more often than I stream anything.

Brent Nongbri on Candida Moss’s recent work: “Overall, this book has an effect that is similar to that of E.P. Sanders’s Paul and Palestinian Judaism (1977). Even if you don’t agree with every interpretive move the author makes, the collective force of the book’s examples leaves you with what can only be described as a new perspective. In other words, if the field takes God’s Ghostwriters seriously (and it should), then there is no going back. And the way forward will involve greater effort to pay attention to the enslaved people who played important parts in producing, promulgating, and preserving the writing of the Roman world.”

If I’m irritible over the next few days, it’s because Apple’s forced reset of my password means that all of my app-specific passwords have been erased and now I have to create new ones. Great.

This award-winning building … is a glass cuboid. The world’s ten billionth glass cuboid.

What happened to Michael Tsai also happened to me today. Annoying as heck. All my Apple devices are confused.

Re: this list of sites that prohibit your linking to anything but their home page — I wonder how it would play out if a dispute about this policy went to court here in the U.S.? What if I linked to a page on Bill Gates’s site and he sued me? What would be the legal basis for his suit, and what would be the best legal defense of my Right To Link? (I suppose my lawyer would have to say something more than “You posted this on the open web, dumbass.")

Like almost every other writer in America, I’ve weighed in on that Elle Griffin nobody-buys-books post – or one implication of it anyway.

advancing

Elle Griffin seems to have carved out a niche for herself telling hard truths to would-be writers – which is an unpleasant but useful service, I think. But there’s one troublesome point I think she actually understresses — though it will take me a few minutes to get to that point.

Griffin cites this chart from Penguin USA:

Category 1: Lead titles with a sales goal of 75,000 units and up Advance: $500,000 and up

Category 2: Titles with a sales goal of 25,000–75,000 units Advance: $150,000-$500,000

Category 3: Titles with a sales goal of 10,000–25,000 units Advance: $50,000- $150,000

Category 4: Titles with a sales goal of 5,000 to 10,000 units Advance: $50,000 or less

Four times in my career I have received Category 3 advances; in two of those cases (The Narnian and How To Think) I ended up with Category 1 sales, thus significantly overperforming my advance. In one case (Breaking Bread with the Dead) I have achieved sales to match the “sales goal,” though not (yet?) enough to earn back my advance; in the fourth case (Original Sin) I underperformed the sales goal.

All this assuming that the above information is correct, which, I dunno.

Anyway, this track record should make it possible for me to get another Category 3 advance, should I want one, and if I can come up with the right proposal. I’m not a sure-fire winner, but I’m a decent bet when I do get a big-house contract. (My academic books don’t figure into this discussion, because while they sell well for academic books, even taken together they don’t make enough money annually to pay my property taxes.)

And if the numbers Griffin cites are correct, the sales of my more successful books put them, to my surprise and puzzlement and discomfort, in the top 5% of published books. It’s true that How to Think has sold more copies than books from the same period by Billie Eilish and Justin Timberlake, which should tell you something – mainly that fans of Billie Eilish and Justin Timberlake don’t read books. I should also add that How to Think really took off for a little while because Fareed Zakaria loved it and hyped it on CNN. Funny old world, ain’t it. But still … the “top 5%” thing just feels wrong.

Anyway, let’s imagine that I receive a $100,000 advance for a future book. Not impossible by any means. The thing is, and this is the point I think Griffin should lean on more heavily: “advance” is a misleading term. Advances don’t come all at once, they come in stages, either three or four of them, for instance:

- $25,000 at contract signing;

- $25,000 at submission of an acceptable (but still to be edited) manuscript;

- $25,000 at publication of the hardcover;

- $25,000 at publication of the paperback, or, if the publisher chooses not to make a paperback, one year after the publication of the hardcover.

(Sometimes the unit payments vary: for instance, for Breaking Bread with the Dead my agent negotiated bigger payouts for the first and third stages, smaller ones for the other two.) In a typical situation, after you sign the contract you might need two years to write the book. Supposing that your manuscript is pretty good and just needs editing, that process can take several months, and then getting the book ready for publication can take several more months. And the final payout will come a year after that initial publication. So while a $100,000 advance sounds like a lot of money, it often ends up being $25,000 a year; not nearly enough to live on.

The moral: Writing books can be a nice supplement to your day job, but it is virtually impossible for it to replace your day job, even if you’re in the top 5% percent of sales. That I, several of whose books appear to be in that category, couldn’t make a decent living if I sold three times as many of those books as I do, should suggest … not, as Griffin keeps saying, that no one buys books, but that the whole industry is smaller than most people think and a money machine for only a handful of writers. You probably have to get into the top 1% of published-by-publishers writers to make a living solely by writing. Probably only a few hundred, or at most a few thousand, people in the entire world manage that. (Griffin seems to think Substack offers a better chance for success, but I bet the percentages there are roughly the same.)

P.S. I’m probably not going to get another significant advance, because I doubt I will ask for one. I can’t at the moment imagine wanting to write a book that a Big Five publisher would want to pay for. That could change, of course, but I don’t expect it will. I decided to write my Sayers biography for a university press rather than a trade house primarily to write the book I wanted to write — not the book I needed to write to earn back an advance.

P.P.S. I see Freddie has weighed in also. Some good thoughts there, but I’m not sure about the title: “Publishing is Designed to Make Most Authors Feel Like Losers Even While the Industry Makes Money.” Maybe that’s right. It’s certainly that advances used to be smaller for the biggest sellers and larger for the mid-list writers, which made it possible for mid-list writers to make a modest but firmly middle-class living — especially when they could supplement their book income with writing for periodicals that, in inflation-adjusted dollars, paid much more than they do now. (Why could so many magazines back in the day pay so much more? Because they got much higher ad revenue in periods when ad money didn’t have nearly as many places to go.) The publishing industry has clearly borrowed the Silicon Valley venture capitalists’ practice of hoping for one or two hits in a thousand investments, but I don’t understand how that affects their decisions about how to distribute the money they have available for advances. I wish I did.

Taken in SE Colorado, March 2023.

Live webcam at Valles Caldera, New Mexico. The webcam is cool but it’s one of those places that simply can’t be appreciated except in person — a photo doesn’t capture the scale of the place.

Reading this because it’s discussed, with considerable energy, in Sayers’s Gaudy Night. 📚

This morning I wrote my most boring post ever! It’s about citations of a literary critic.

influence and citation

I have an essay coming out in the July issue of Harper’s which I titled “The Mythical Method” but which will probably end up with the title “Yesterday’s Men: The Death of the Mythical Method.” It concerns the rise and fall of myth as a central, or perhaps at times the central, concept of humanistic study; and therefore it has some things to say about Northrop Frye’s former influence over the humanities and especially over literary criticism.

Perhaps the most prominent scholar of Northrop Frye’s work is Robert D. Denham, who has repeatedly written — see for instance this 2009 essay — that the rumors of Frye’s repetitional demise are greatly exaggerated, and that “if Frye is no longer at “the center of critical activity,” as he was in the mid-1960s, he still remains very much a containing presence at the circumference.” Denham continues,

In 1963 Mary Curtis Tucker wrote the first doctoral dissertation on Frye. The period between 1964 and 2003 saw another 192 doctoral dissertations devoted in whole or part to Frye, “in part” meaning that “Frye” is indexed as a subject in Dissertation Abstracts International. The number of dissertations for each of the decades falls out as follows: 1960s = 5; 1970s = 28; 1980s = 63; 1990s = 68; and in the first four years of the present decade, 29.3. These data obviously indicate that during the twenty-year period following the height of the post-structural moment, interest in Frye as a topic of graduate research substantially increased.

I mention all this because this is an interesting case of how statistics can mislead when context is eliminated. In citing these numbers Denham omits some important information:

- The rise of literary theory as a subset of literary studies. When Mary Curtis Tucker wrote that first dissertation on Northrop Frye, people in English studies simply didn’t write dissertations on other academic literary critics. The rise of theory as a sub-discipline changed that.

- The overproduction, especially in the humanities, of PhDs — something that has been worried over since I was in grad school.

If in 2009, when Denham published that essay, we saw (a) far more PhDs in English being produced than had been the case in in 1963 — a trend that, inexplicably and indefensibly, continued for several more years — and (b) a far larger percentage of dissertations focusing on contemporary literary criticism and theory than had been the case in 1963, then it becomes clear that citations of Frye could rise in absolute numbers during the same period when Frye’s influence was significantly decreasing proportionate to the whole discourse.

In a recent book, Denham goes beyond his 2009 argument to say that there has been an “exponential progression” to Frye’s influence. But here he is relying on dissertations from places like the University of Peking and even the University of Inner Mongolia in Hoh-Hot (now known as Inner Mongolia University). But how many dissertations on any topic in English literature or literary theory and criticism would have been produced in those universities forty or forty years ago? Denham is making comparative judgments without a fixed or appropriate baseline of comparison. “People say that the Sega Genesis console is obsolete, but far more people use them today than used them in 1987!”

(In so doing — I say this only in passing — Denham is missing what could be a really fascinating point: I’d be willing to bet that Chinese students of Western literary criticism and theory will, generally speaking, find Northrop Frye more interesting and useful than, say, Judith Butler. That would be a topic worth exploring.)

There is another issue also: “citation” is a word that captures a wide range of possibilities. In the 1960s and 1970s, Frye’s work could be cited to clinch a point — if you could get Northrop Frye on your side you could win an argument. But since then Frye has typically been cited in North America and Great Britain as a representative of a Eurocentric false universalism, a residual Christian imperialism, a putatively apolitical totalizing discourse of patriarchy — that kind of thing: citing him not because he’s on the winning side but because his side isn’t winning any more, thank God.

But of course, as Oscar Wilde said, the only thing worse than being talked about is not being talked about.

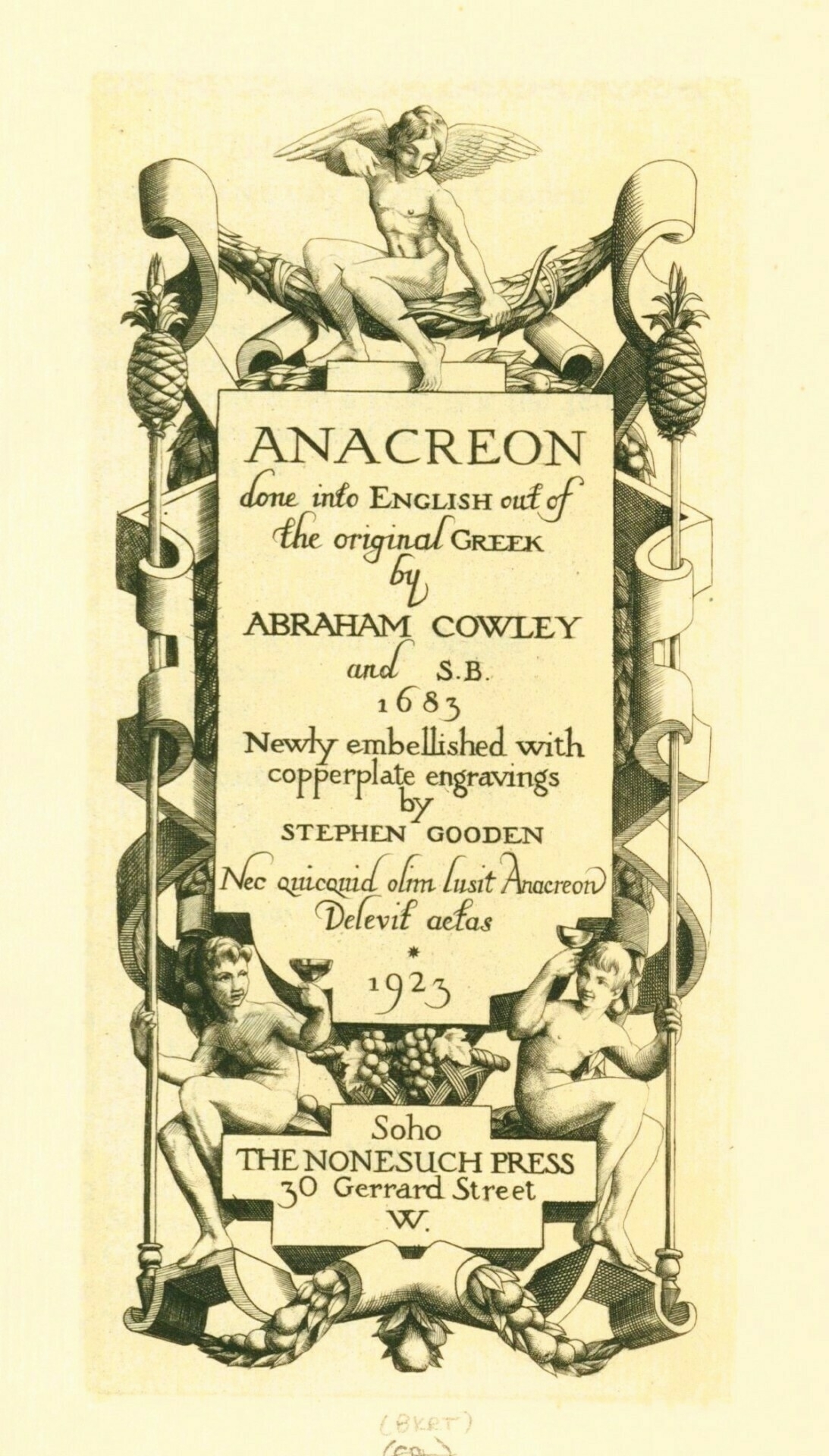

UW-M Special Collections – one of my favorite Tumblrs.