UW-M Special Collections – one of my favorite Tumblrs.

more on costs and choices

Isaiah Berlin, “The Originality of Machiavelli”:

The ideals of Christianity are charity, mercy, sacrifice, love of God, forgiveness of enemies, contempt for the goods of this world, faith in the life hereafter, belief in the salvation of the individual soul as being of incomparable value - higher than, indeed wholly incommensurable with, any social or political or other terrestrial goal, any economic or military or aesthetic consideration. Machiavelli lays it down that out of men who believe in such ideals, and practise them, no satisfactory human community, in his Roman sense, can in principle be constructed. It is not simply a question of the unattainability of an ideal because of human imperfection, original sin, or bad luck, or ignorance, or insufficiency of material means. It is not, in other words, the inability in practice on the part of ordinary human beings to rise to a sufficiently high level of Christian virtue (which may, indeed, be the inescapable lot of sinful men on earth) that makes it, for him, impracticable to establish, even to seek after, the good Christian State. It is the very opposite: Machiavelli is convinced that what are commonly thought of as the central Christian virtues, whatever their intrinsic value, are insuperable obstacles to the building of the kind of society that he wishes to see; a society which, moreover, he assumes that it is natural for all normal men to want - the kind of community that, in his view, satisfies men’s permanent desires and interests. […]

It is important to realise that Machiavelli does not wish to deny that what Christians call good is, in fact, good, that what they call virtue and vice are in fact virtue and vice. Unlike Hobbes or Spinoza (or eighteenth-century philosophes or, for that matter, the first Stoics), who try to define (or redefine) moral notions in such a way as to fit in with the kind of community that, in their view, rational men must, if they are consistent, wish to build, Machiavelli does not fly in the face of common notions — the traditional, accepted moral vocabulary of mankind. He does not say or imply (as various radical philosophical reformers have done) that humility, kindness, unworldliness, faith in God, sanctity, Christian love, unwavering truthfulness, compassion are bad or unimportant attributes; or that cruelty, bad faith, power politics, sacrifice of innocent men to social needs, and so on are good ones.

But if history, and the insights of wise statesmen, especially in the ancient world, verified as they have been in practice (verità effettuale), are to guide us, it will be seen that it is in fact impossible to combine Christian virtues, for example meekness or the search for spiritual salvation, with a satisfactory, stable, vigorous, strong society on earth. Consequently a man must choose. To choose to lead a Christian life is to condemn oneself to political impotence: to being used and crushed by powerful, ambitious, clever, unscrupulous men; if one wishes to build a glorious community like those of Athens or Rome at their best, then one must abandon Christian education and substitute one better suited to the purpose.

I think Berlin is right about Machiavelli, and I think Machiavelli is right about Christianity too. The whole argument illustrates Berlin’s one great theme: the incompatibility of certain “Great Goods” with one another. The more I think about it, the more convinced I am that the inability to grasp this point is one of the greatest causes of personal unhappiness and social unrest. Millions of American Christians don’t see how it might be impossible to reconcile (a) being a disciple of Jesus Christ with (b) ruling over their fellow citizens and seeking retribution against them. Many students at Columbia University would be furious if you told them that they can’t simultaneously (a) participate in what they call protest and (b) fulfill the obligations they’ve taken on as students. They want both! They demand both!

Everybody wants everything, that’s all. They’re willing to settle for everything.

See my recent post on costs and the “plurality” tag at the bottom of this post.

Probing his riding companions, Robert [Pirsig, in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance] comes to understand that John and Sylvia’s attitude of non-involvement with “technology” is emblematic of a wider phenomenon that was then emerging, a countercultural sensibility that seeks escape from the Man and all his works: “the whole organized bit,” “the system,” as they put it. The solution, or rather evasion, that John and Sylvia hit on for managing their revulsion at technology is to “Have it somewhere else. Don’t have it here.” The irony is that they ride their motorcycle out into the countryside to escape this “death force” that is trying to turn them into “mass people,” and it is precisely in these moments that they find themselves most intimately entangled with The Machine - the one they sit on. This dependence is an affront to their own sense of themselves as cultural dissidents. The problem, then, cuts rather deep. They are living a contradiction. It’s a bit like using Substack to write critiques of technology.

I wrote about how I decide what literary fiction not to read.

rational choices

The race is not always to the swift, nor the battle to the strong; but that is the way to bet.

There’s too much to read, right? Especially contemporary fiction. Too many choices. You have to develop a strategy of selection, a method of triage. I will always read more old books than new ones, as I think everyone should. But I don’t neglect what my contemporaries are doing. This summer, for instance, I plan to read Jon Fosse’s Septology and Zito Madu’s memoir The Minotaur at Calle Lanza. (Memoir is not fiction, of course, but it uses some of the same techniques and, for me, scratches some of the same itches.)

My own strategy for deciding what to read arises from these facts: Literary fiction in America has become a monoculture in which the writers and the editors are overwhelmingly products of the same few top-ranked universities and the same few top-ranked MFA programs — we’re still in The Program Era — and work in a moment that prizes above all else ideological uniformity. Such people tend also to live in the same tiny handful of places. And it is virtually impossible for anything really interesting, surprising, or provocative to emerge from an intellectual monoculture.

With these facts in mind I have developed a three-strike system to help me decide whether to read contemporary fiction, with the following features:

- The book is set in Brooklyn: Three strikes, you’re out.

- The author lives in Brooklyn: Three strikes, you’re out.

- The book is set anywhere else in New York City: Two strikes.

- The book is set in San Francisco: Two strikes.

- The book’s protagonist is a writer or artist or would-be writer or would-be artist: Two strikes.

- The author attended an Ivy League or Ivy-adjacent university or college: Two strikes.

- The book is set in Los Angeles: One strike.

- The author lives in San Francisco: One strike.

- The author has an MFA: One strike.

- The book is set in the present day: One strike.

I am not saying that any book that racks up three strikes cannot be good. I am saying that the odds against said book being good are enormous. It is vanishingly unlikely that a book that gets three strikes in my system will be worth reading, because any such book is overwhelmingly likely to reaffirm the views of its monoculture — to be a kind of comfort food for its readers. Even books as horrific as Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life — a novel I wish I had never read, and one of the key books that made me settle on this system — is comforting in the sense that we always know precisely whom we are to sympathize with and whom to hate. Daniel Mendelsohn is correct: “Yanagihara’s book sometimes feels less like a novel than like a seven-hundred-page-long pamphlet.” I would delete “sometimes.”

(Author graduated from Smith College, lives somewhere in New York City, book is set in New York City in more-or-less the present day: at least five strikes. I shoulda known.)

My system does not cover every eventuality. Among other things, it only applies to American writers, though the monoculture I have described extends overseas: for instance, Sally Rooney doesn’t live in Brooklyn, but she might as well; and her books aren’t set in Brooklyn, though they might as well be. I need to extend my system to account for this kind of thing. But I can continue to work on that.

I have a similar system for deciding whether to watch a movie; maybe I’ll write about that in another post.

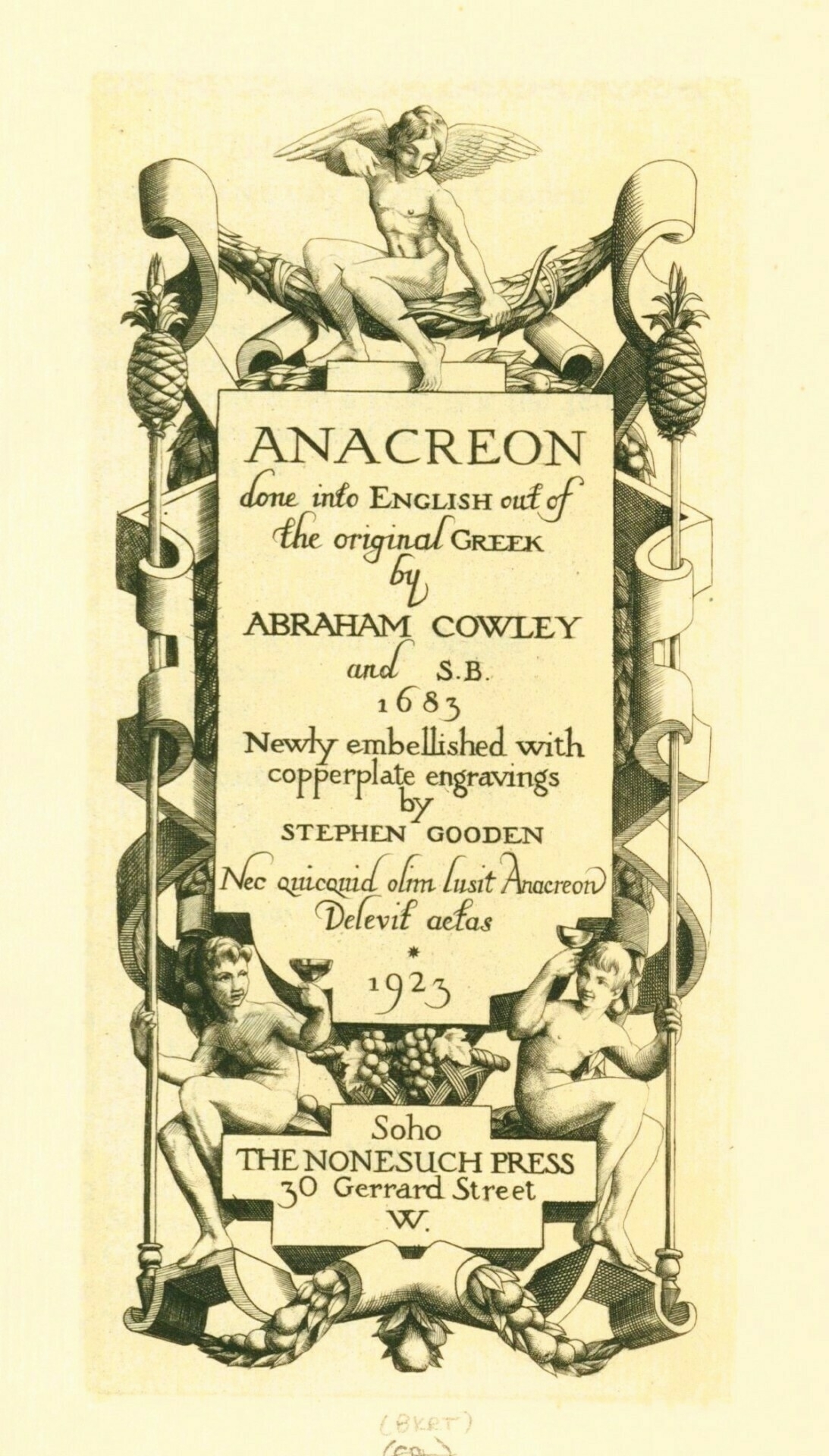

I just love type in cases.

The Guardian: “As people get older, they revise the age they consider to be old upwards.” This is good for me to know, since before too long I will officially be middle-aged.

Currently reading: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. I wrote a post about returning to this great book. 📚

Gilead revisited

The way we speak and think of the Puritans seems to me a serviceable model for important aspects of the phenomenon we call Puritanism. Very simply, it is a great example of our collective eagerness to disparage without knowledge or information about the thing disparaged, when the reward is the pleasure of sharing an attitude one knows is socially approved. And it demonstrates how effectively such consensus can close off a subject from inquiry. I know from experience that if one says the Puritans were a more impressive and ingratiating culture than they are assumed to have been, one will be heard to say that one finds repressiveness and intolerance ingratiating. Unauthorized views are in effect punished by incomprehension, not intentionally and not to anyone's benefit, but simply as a consequence of a hypertrophic instinct for consensus. This instinct is so powerful that I would suspect it had survival value, if history or current events gave me the least encouragement to believe we are equipped to survive.

– Marilynne Robinson, “Puritans and Prigs” (1996)

I’m re-reading Gilead now, in preparation for teaching it, and I am struck all over again by what an extraordinary book it is, what a gift it has been to so many readers — millions of them, maybe. (Promotional material for the book has long shouted A MILLION COPIES SOLD, but the count might be two million by now, and of course many thousands of people have read used and library copies.) Really, it’s some kind of miracle. The novels that have followed it are excellent novels indeed, but they aren’t miraculous. Gilead certainly is.

But today, twenty years later, would Gilead even be published by a big trade house? As long as the author could say that she teaches at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, probably. Would it be widely read and celebrated? Almost certainly not. The self-appointed cultural gatekeepers would denounce it as a project of white cis-het imperialism, and trepidatious reviewers would either ignore it or offer, at best, muted praise. And if it were a first novel, it might not get published at all — though perhaps an outfit like Belt Publishing would take it on.

As I read Gilead today it still feels like a great gift, but also an artifact of a lost era.

costs

A brief follow-up to this post from last week: In our current climate of political assholery, no self-described “activist” can answer what I think of as an essential question: If you get what you want, what will be the costs? Every choice — every choice ever made by every human being — carries costs. Some of the costs are easily borne; some, though, are unmanageable, or even catastrophic. Especially if you’re a political activist, you have a responsibility to anticipate the costs of your preferred policy and develop a plan for dealing with them. But if you ask people who call themselves activists the question above, you’ll only get two responses: dumfounded blankness or sheer rage.

Me: I just spilled hot coffee all over my chest!

My son: Oh no! Is the coffee okay??

I wrote an extremely spoilery post about Gene Wolfe’s strange novel Peace.

Peace, Peace

N.B. This post is spoilerful.

A few years ago I read a fascinating post by my colleague Philip Jenkins about Gene Wolfe’s 1975 novel Peace. I had read Peace many years ago but didn’t remember anything about it, and Philip’s post reminded me that there’s a complicated discourse surrounding the book. I decided that I wanted to re-read the book without looking at the interpretations … and only now have I gotten around to it. Here are some things that struck me:It seemed obvious to me that our narrator, Alden Dennis Weer, is dead and is revisiting his life. (Wolfe has cheerfully confirmed that Weer is a ghost.) He clearly lives, or “lives,” in a rambling memory palace of his own making, each room of which is related to some season of his life. But the palace is not complete, and he can temporarily or permanently lose access to some of its rooms.

Severian, the protagonist and narrator of Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun tetralogy — which Wolfe began almost immediately after writing Peace — claims to have a perfect memory, and perhaps he does, but he does not tell us everything he remembers. When he remains silent about some episode in his life, the reader has to sift the evidence to figure out what really happened, or wait for later evidence. The same is true of Weer’s narration in Peace. Often he leaves stories unfinished — and by “stories” I mean both his direct narration of his life’s events and the book’s many tales (some of them fairy tales, some of them anecdotes told to him by others). It’s possible that he has forgotten how some stories end, but in many of the cases he simply does not want to say what happened, and we are left to draw inferences. He does not narrate the death of his Aunt Olivia, but we can piece together an account of her death. He explicitly says that he will not tell us what happened when he and the librarian Lois Arbuthnot visited a farm outside of town to search for an old document, but later it becomes pretty clear what happened: Weer killed her. (And she may not be the only person he murders.)

When declining to tell that story, Weer writes,

You must excuse me. I can write nothing more now about the trip Lois and I made to Gold's, or our search for the buried treasure. Everything we do is unimportant, I know; but some things are, if not more important, at least more immediate than others, and so I must tell you (writing alone in this empty room, my pen scratching on the paper like a mouse in a wall) that I am very ill. Sicker, I think, than I have ever been before — sicker, even, than I was this winter, before Eleanor Bold's tree fell.The falling of that tree — called Eleanor Bold’s because she planted it, but the key point is that she planted it over Weer’s grave — is what awakens his spirit (Wolfe confirmed this in an interview) and inaugurates his assessment of his life. Trees can live a long time, and there’s a hint early in the book that Weer knows himself to be a ghost, and a ghost haunting the place where he had lived long, long before:

And as if by magic — and it may have been magic, for I believe America is the land of magic, and that we, we now past Americans, were once the magical people of it, waiting now to stand to some unguessable generation of the future as the nameless pre-Mycenaean tribes did to the Greeks, ready, at a word, each of us now, to flit piping through groves ungrown, our women ready to haunt as lamioe the rose-red ruins of Chicago and Indianapolis when they are little more than earthen mounds, when the heads of the trees are higher than the hundred-and-twenty-fifth floor — it seemed to me that I found myself in bed again, the old house swaying in silence as though it were moored to the universe by only the thread of smoke from the stove.This narration, then, may take place hundreds of years in the future.

What is the term of Weer’s haunting? Will he forever be a ghost? Or is he, perhaps, like Hamlet’s father, “Doom’d for a certain term to walk the night … Till the foul crimes done in my days of nature / Are burnt and purged away”? I am inclined to believe the latter. That is, I think that Weer will wander through the rooms of his memory until he remembers, and faces, it all. His old house is a purgatorial mansion. (That word makes me wonder whether there is a thematic connection between Peace and an even weirder book by Wolfe’s fellow Roman Catholic SF writer, R. A. Lafferty: Fourth Mansions.)

Those who know Alden Dennis Weer best call him Den, which is interesting because that’s the second half of his first name and the first half of his second name. Den/Den. I take this to indicate that he is a doubled self — like Dr. Jekyll, and like the Major Weir (!) Philip discusses in his post — and may be liberated from his complicated prison only when he has confronted and acknowledged all that he currently denies or evades. Then and only then will he have peace. The title of the novel thus points to what’s missing from it.

The various interpolated tales in Peace comment in various ways on the events that Weer narrates and the people that he knew. For instance, one story about a princess and her suitors clearly mirrors Aunt Olivia and her suitors. And late in the novel the bookseller and forger Mr. Gold reads a tale to Weer that I think is meant to describe to Weer his own situation. The tale comes, Gold says, from a book called The Book That Binds the Dead, though he comments that “It may not be as easy to hold the dead down as we think.” Be that as it may, in the passage Gold reads a man describes how he and a friend tried to summon the spirit of a dead man. They stand over his grave, and eventually he rises before them:

The flesh of his head was as the dust, and there remained only his hair, which hung to his shoulders as in life, but had lost its luster and had in it certain of those small animals which the sun engenders in that which no longer has life. His eyes were no more; their sockets seemed dark pits, save that there flickered behind them a point of light that moved from one to the other and often was gone from both, and appeared just such a spark as is seen at night when the wind blows a fire that is almost gone, and perhaps a single spark, burning red, flies hither and thither in the black air. From what the spirit, that mighty one, had whispered to me, I knew this spark for the soul of the dead man, seeking now in all the chambers under the vault of the skull its old resting places.What does he mean by “the day that is mine”? It is, I think, the day of his purgation. We should remember Pope Adrian V in Dante’s Purgatorio, who speaks briefly the pilgrim but then asks him to go away: “Your presence here distracts me from the tears that make me ready.” The spirit the men in this tale have raised is a true image of Alden Dennis Weer.Then, gathering all my courage, and recollecting what the spirit had divulged to me — that the dead man was not like to harm me save I set my foot upon his grave, or cast aside one of the stones that had sheltered him from the jackals — I spoke to him, saying, “O you who have returned where none return. You waked from the death that men say never dies; speak to us the knowledge of the place from which you have come.”

Then he said to us, “O shades of the unborn years, depart from me, and trouble not the day that is mine.”

I have tried in the above to outline what I think is fundamentally going on in Peace — but what I say has relatively little overlap with the vast online literature about the novel, which, now that I’ve looked it over in the aftermath of my reading, seems mainly concerned to trace the staggeringly dense and complex web of reference that Wolfe weaves into this novel, as he does into most of his stories. To mention just one tiny example that I noticed as I read: Weer early on mentions his childhood fascination with Andrew Lang’s Green Fairy Book, which (I reminded myself by checking Wikipedia) contains a version of the old French fairy tale “The Blue Bird,” in which a man is transformed into a bird. And then one of the characters in Peace narrates his encounter with a man who is gradually being transformed into stone — a man whom he meets in The Bluebird Cafe. This led me to notice the number of characters in the novel who are compared to birds; and I also started thinking of the characters’ various metamorphoses. Aunt Olivia, for instance, once described as being “all bird bones and petticoats,” eventually becomes a corpulent woman whom Weer sees naked in her bath. Plus, “The Blue Bird” also concerns magic eggs, and a major event in Peace involves the quest for a rare and beautiful painted egg.

There is no end to this kind of thing in Wolfe’s fiction: he knits and purls, always stitching stitching stitching, ever complicating the weave, to a degree that seems to me compulsive and often, frankly, counterproductive. The (largely online) discourse about his books is obsessed with these fancy stitchings, and you can read thousands and thousands of words about this connection and that, this allusion and that, without ever finding anyone who asks what a given book is about, why it exists.

I’m reading a lot of mysteries these days, in preparation for a biography of Dorothy L. Sayers, and readers of mysteries may be divided into two camps, those who want to find a good puzzle to solve and those who want to read an interesting story. You can also, generally speaking, divide the writers of mysteries into two camps: those who want to please the puzzle solvers and those who want to please the story lovers.

Gene Wolfe is likewise a maker of puzzles and a teller of tales, and I often find myself wondering which he cared about more. If you look at the online commentary on Wolfe’s novels, you might think that the puzzles are the only things that matter, and certainly Wolfe gives us a superabundance of teasing clues. I call that superabundance “counterproductive” because I like stories more than puzzles — which is also why I’d rather read Dorothy L. Sayers than John Dickson Carr. When reading Wolfe’s fiction I am often frustrated, because I find that the complications of the weave obscure the design of the story. In my reflections above I have tried to set aside many of the puzzles in order to focus on the matters I find essential. But maybe occluding the distinction between the essential and inessential is just what Wolfe wants to do.

The OED has just added 23 Japanese words, mainly involving food and entertainment.

High is Adam Roberts in his thriller mode. Think: Mission: Impossible on Mars. Brilliant. So much fun. 📚

Oleander is enthusiastic.

I wrote a post on how anarchic childhoods can make more politically mature adults.