People sometimes respond to my essay on anarchism by calling me a libertarian. But — to give a very brief account of an important issue — I think libertarianism and anarchism are quite different. The goal of libertarianism is to increase individual liberty, while the goal of anarchism is to expand the realm of cooperation and collaboration.

Good to hear that txt.fyi will be coming back. It was the best way to post chunks of text that you didn’t necessarily want on your own site or exposed to the toxicity of social media. People only saw it if they had the link. I didn’t use it often, but it was great to have around for special cases.

Narayan's Malgudi

In his newsletter today, my buddy Austin Kleon mentions in passing the Hindu concept of the ashramas or stages of life, which is funny because I’ve just been thinking about a novel based on those stages: The Guide, by R. K. Narayan.

Narayan was a great, great genius, and maybe the best comic novelist since P. G. Wodehouse. His comedy is different than Wodehouse’s — it’s pretty quiet and gently ironic. But he’s very funny! Narayan’s novels and short stories — he’s a masterful writer of short stories — are set in the fictional town of Malgudi in southern India. See the map above, from my old copy of his short-story collection Malgudi Days, which is bad because it’s just an iPhone photo. (I need to buy a flatbed scanner.)

Here’s one example of Narayan’s humor, from one of my favorites among his novels, The Painter of Signs (1976). Rajan, the sign-painter of the title, is a man with strong views about his profession — he knows precisely the kind of lettering appropriate for every commission — and considers himself a “rationalist”: “I want a rational explanation for everything. Otherwise my mind refuses to accept any statement.” (He’s always arguing with his aunt, who insists that his actions should be governed by the mandates of astrology.)

But his rationalism starts to fray when he agrees to paint a sign for the local Family Planning Centre, because said Centre is run by a highly progressive and single-minded young woman who rejoices in the improbable name of Daisy. Raman goes weak in the knees at his first sight of her.

Having written signboards for so many years, it was rather strange that he should be presented with a female customer now, and that it should prove so troublesome. He was going to shield himself against this temptation. Mahatma Gandhi had advised one of his followers in a similar situation, ‘Walk with your eyes fixed on your toes during the day, and on the stars at night.’ He was going to do the same thing with this woman. He would not look at her eyes when he met her, nor involve himself in any conversation beyond the strictest business.

Unfortunately, he almost immediately runs into Daisy when he has no time to prepare himself. On impulse, just before entering the Family Planning Centre to discuss his commission, he buys a cheap pair of sunglasses, recommended to him by the vendor as made in Hong Kong. When he enters her office he’s wearing the sunglasses:

He had been talking to her with his eyes looking away, but now he lifted his eyes in her direction, looked through his glasses. He noticed that she seemed heavy-jowled and somewhat ridiculous, with her forehead slightly tapering. The Hong Kong optician has excelled in his art, he thought. She looks terrible. This is even better than Gandhi's plan to keep one’s mind pure. She seemed to grin, and looked like a demoness!

I’ll leave it to you to find out what happens next.

Another great Malgudi novel is Man-Eater of Malgudi (1961), which concerns a printer named Nataraj who makes the catastrophic mistake of renting space in his attic to Vasu, a taxidermist (that “nefarious trade,” thinks Nataraj) who, it turns out, is very well-connected among Malgudi’s professional dancing-girls.

But perhaps my favorite is the aforementioned The Guide (1958), which concerns an utterly corrupt tourist guide named Raju who, after being released from prison, finds himself wandering in search of a new home and a new life. He camps out in an abandoned temple, at which point some of the local villagers take him for a holy man. And why should he disabuse them of that notion?

Ladies and gentlemen, take my advice: Pay a visit to Malgudi. You won’t regret it.

One of the first reviewers of Tolkien’s Silmarillion was Richard Adams, of Watership Down fame. Spoiler: He adored it.

everyone knows

Reading this Jessica Grose piece — so similar to ten thousand other reports made in recent years — on the miseries induced or exacerbated by digital technologies in the classroom, I think: Everyone knows all this.

Everyone knows that living on screens is making children miserable in a dozen different ways, contributing to ever-increasing rates of mental illness and inhibiting or disabling children’s mental faculties.

Everyone knows that engaging creatively with the material world is better for children — is better for all of us.

Everyone knows that Meta and TikTok are predatory and parasitical, and that they impoverish the lives of the people addicted to them.

Everyone knows that social media breed bad actors: each platform does this in its own way, but they all do it, and the more often people engage on such platforms the more messed-up and unhappy they become.

Everyone knows that the big Silicon Valley companies do not care how much damage they do to society or the environment; they care only about what Mark Zuckerberg likes to call DOMINATION. The occupational psychosis of Silicon Valley is sociopathy. The rise of LLMs is simply the next big step in this sociopathic program.

Everyone knows all this. Some people, for their own reasons, choose to deny it, but even they know it — indeed, probably no one knows all that I’ve been saying better than Mark Zuckerberg and Shou Zi Chew and Sam Altman do.

So our problem is not a lack of knowledge; it’s a deficiency of will and a malformation of desire. St. Augustine explained it all to us 1600 years ago: My actions are determined by my will, and my will is driven by what I love. We do badly by our children because we do not love them sufficiently or properly; we do badly by our neighbors for the same reason; we do badly by ourselves for the same reason, because narcissists — and one of the things everyone knows is that all the forces named above breed narcissists — do not rightly love themselves.

Those of us who care about the future of our children, our neighbors, and ourselves don’t need to repeat what everyone already knows. We need to devote our full attention to one question and one question only: How do we love rightly and teach others to love rightly? If that’s not our constant meditation, we’re wasting our time. If we cannot redirect our desires towards better things than Silicon Valley, AKA Vanity Fair, sells, then nothing, literally nothing, will get better.

P.S. Why didn’t I remember Leonard Cohen’s “Everybody Knows” when I wrote this post? Austin Kleon reminded me. This is what in footy is called “missing a sitter.”

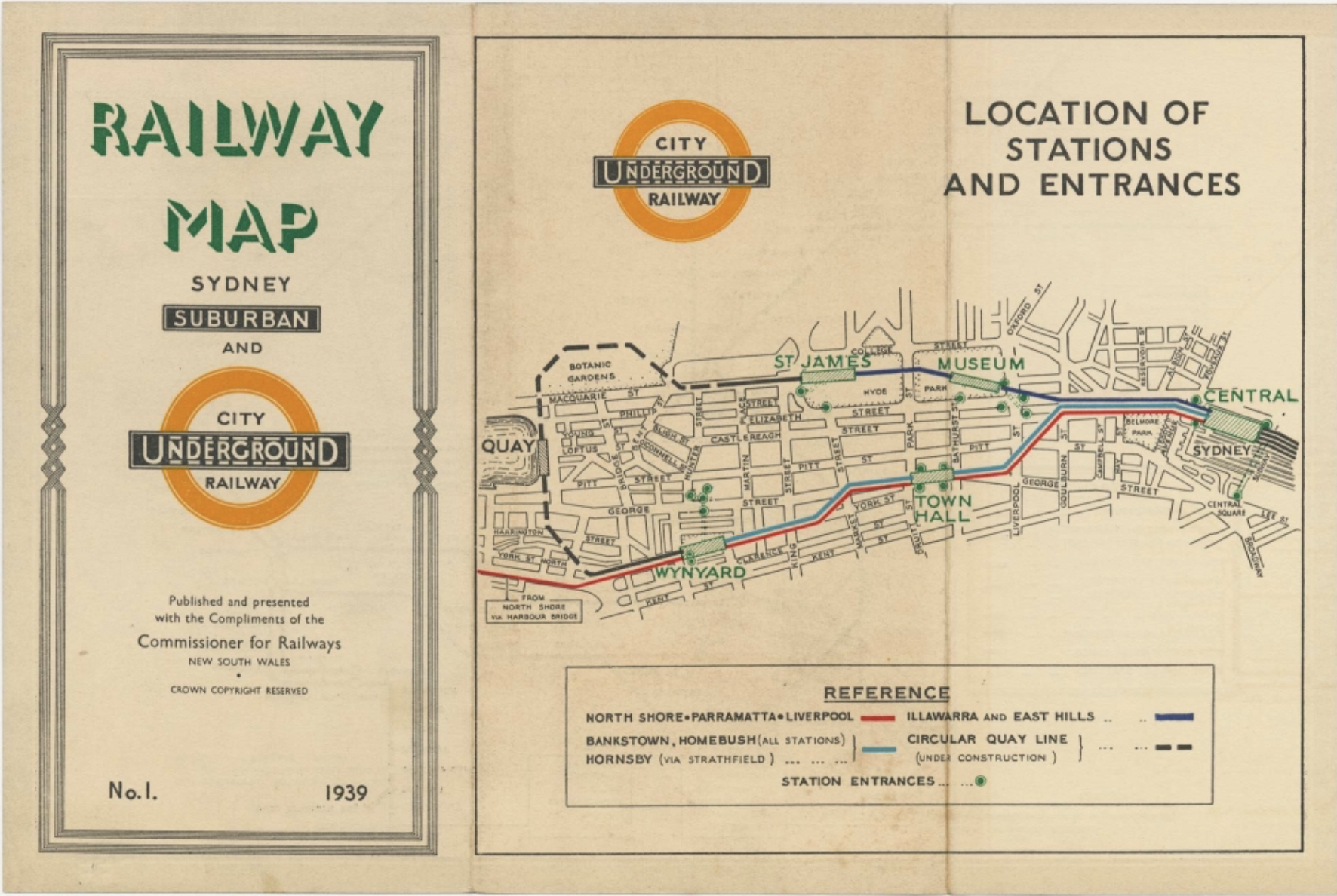

Sydney Railway map, 1939

I love to see this terrific profile of Khruangbin, one of my favorite current bands, but I miss the days when listening to Khruangbin felt like a secret pleasure that you didn’t really want to share widely. ♫

I’m reading Nicholas Jenkins’s The Island: War and Belonging in Auden’s England — it won’t be released until June — and it’s staggering. I didn’t think anyone could still write this kind of book: biographical, cultural, critical, moving easily between the close reading of poetic lines and tracing the sweep of vast social movements. I’ll be reviewing it later for The Hedgehog Review, but for now here’s my three-word review: it’s a masterpiece.

The last eclipse: “The last total solar eclipse will occur when the largest-looking moon just barely covers the smallest-looking sun. A bit of math involving the diameter of the moon and the apparent sizes of the moon and the sun yields an estimate for that eventuality of approximately 620 million years.”

The eclipse as seen from a weather satellite (time-lapse photo).

I’m sorta digging these slightly wrong pictures. (“Wrong” in the sense that I didn’t remember to disable the various software “corrections” to the image.) They sort of look like scenes from Malick’s The Voyage of Time.

The eclipse, partial right now, is overwhelming my camera sensor, but this photo still looks kinda Genesis 1-ish.

A justly famous image from Black Narcissus

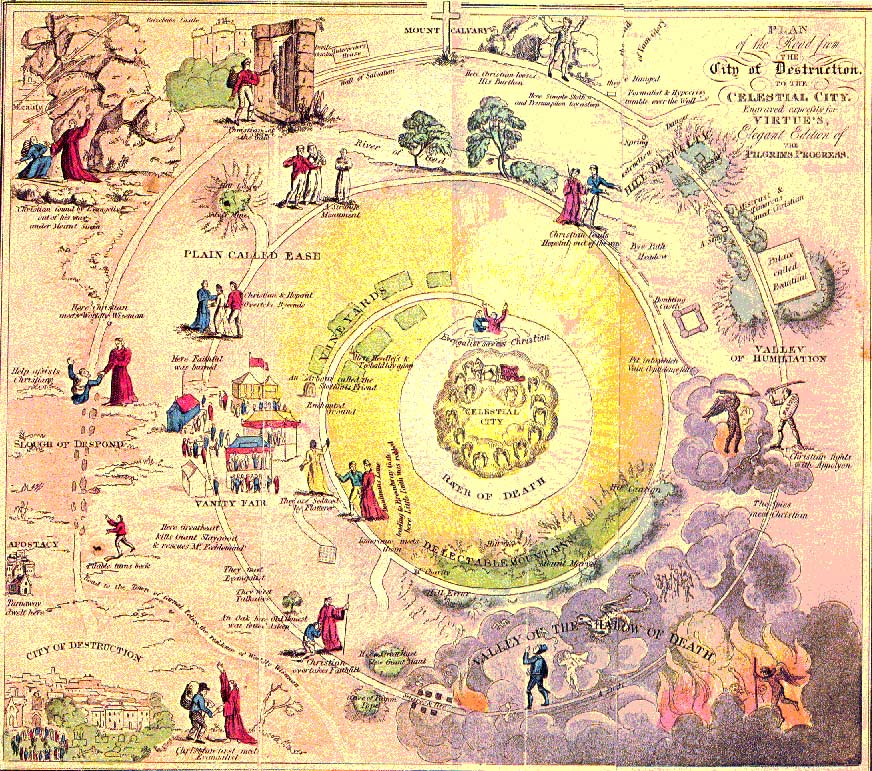

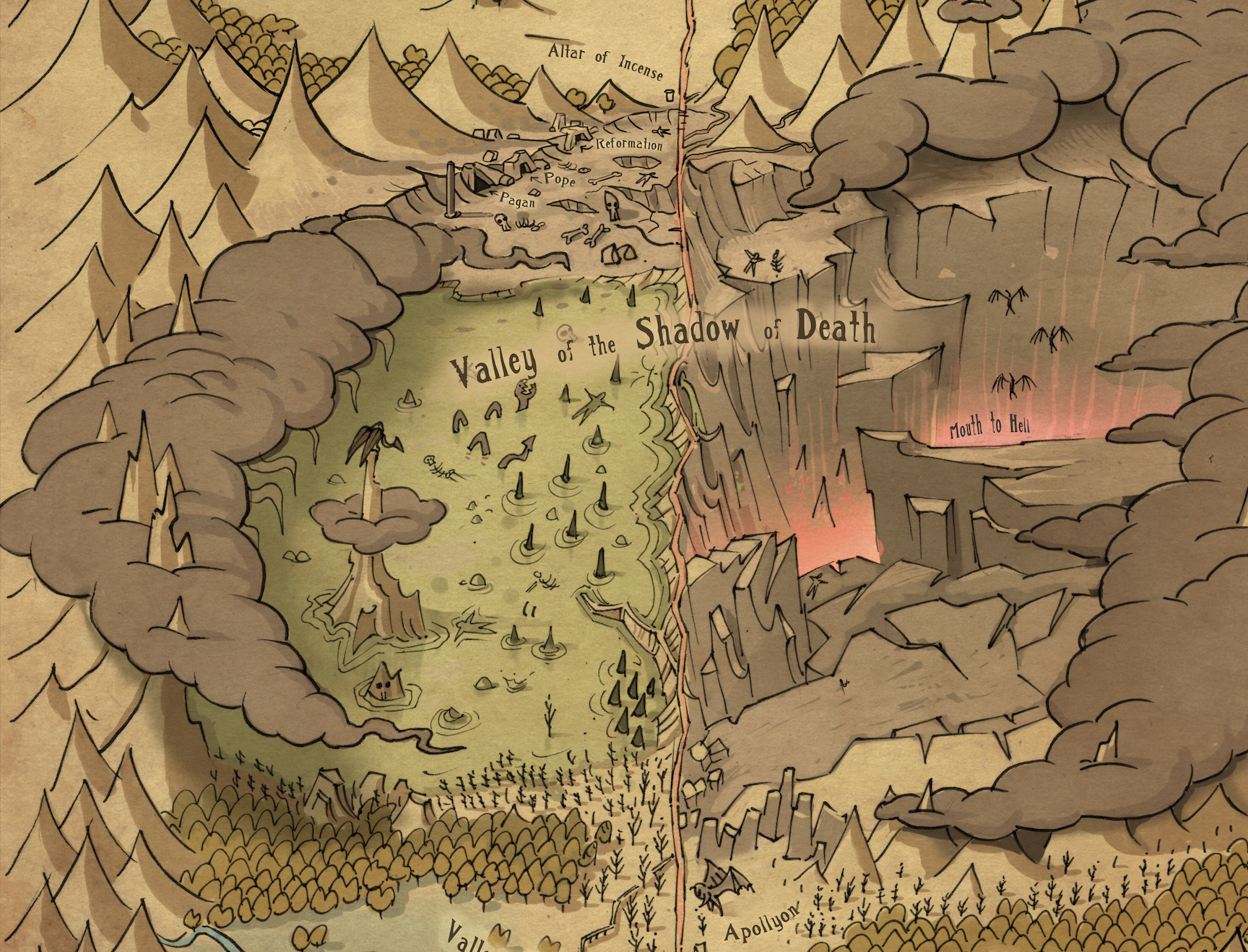

I wrote about The Pilgrim’s Progress and maps thereof. This should perhaps be read in conjunction with my review, from a few years back, of an amazing book called The Writer’s Map: An Atlas of Imaginary Lands.

to be a pilgrim

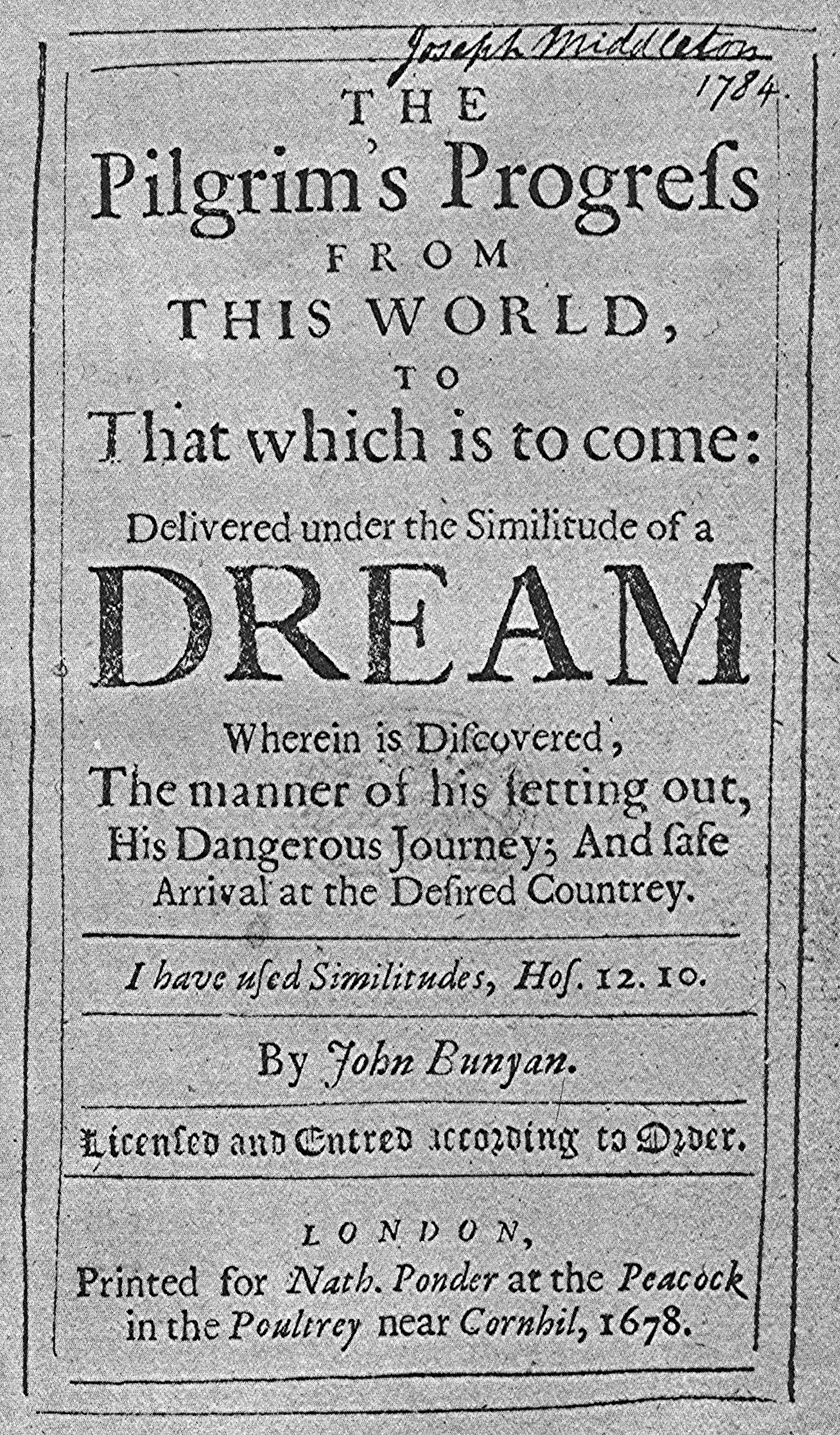

I’ve been teaching The Pilgrim’s Progress, something that always gives me great joy. I find it simply wonderful that so utterly bonkers a book was so omnipresent in English-language culture (and well beyond) for so long. You couldn’t avoid it, whether you loved it — as George Eliot’s Maggie Tulliver did, and lamented the sale of the family’s copy: “I thought we should never part with that while we lived” — or found it puzzling, as Huck Finn did when he recalled the books he read as a child: “One was ‘Pilgrim's Progress’, about a man that left his family it didn't say why. I read considerable in it now and then. The statements was interesting, but tough.”

One of the “tough” things about the “statements” is the way they veer from hard-coded allegory to plain realism, sometimes within a given sentence. One minute Moses is the canonical author of the Pentateuch, the next he’s a guy who keeps knocking Hopeful down. But the book is always psychologically realistic, to an extreme degree. No one knew anxiety and terror better than Bunyan did, and when Christian is passing through the Valley of the Shadow of Death and hears voices whispering blasphemies in his ears, the true horror of the moment is that he thinks he himself is uttering the blasphemies. (The calls are coming from inside the house.)

It seems likely that the last major cultural figure to acknowledge the power of Bunyan’s book is Terrence Malick, who begins his movie Knight of Cups with a voice declaiming the full title of the book: “The pilgrim's progress from this world to that which is to come, delivered under the similitude of a dream; wherein is discovered the manner of his setting out, his dangerous journey, and safe arrival at the desired country.”

Those words are uttered by John Gielgud, because they are taken from a 1990 performance of Ralph Vaughan Williams’s The Pilgrim’s Progress: A Bunyan Sequence, which is a work that Vaughan Williams wanted to compose for his whole life, but only got to near his life’s end: it is his final operatic composition. And it’s wonderful.

The Pilgrim’s Progress is almost always illustrated, and prominent among those illustrations are maps. Here’s a post about those maps. From that post I learned that Garrett Taylor — an artist and animator who has worked for Pixar and on The Wingfeather Saga TV series — has mapped The Pilgrim’s Progress is four prints that you can buy here. I bought them and had them framed and they now adorn a wall of our house. I stop to look at them three or four times a day.

It would be wrong for me to post the full-resolution images here, but I think I can risk one portion of one image:

Now, if Mr. Taylor can just convince Pixar to film the whole book….

Sabine Hossenfelder’s story in this video offers a great illustration of the perverse incentives that afflict academia.

A life of Benjamin Franklin with wood engravings