Fascinating from Ethan Iverson on the Duke: “Who even knows the right changes to Ellington hits? I remember my first attempts to learn famous Ellington tunes: when I eventually heard the Ellington versions, they seemed wrong, since the changes were so different than what were in the fakebooks and on everybody else’s records. Even functions as obvious as tonic and dominant could be reversed. And Duke’s middle voices — his counterpoint! — frequently went by too thick and too fast to be reducible to changes. (Of course, that’s true of any reasonably sophisticated big band writing, but my gut tells me it’s harder to make a really good cheat sheet of Duke than just about anybody else.)” ♫

I’m on a Duke Ellington kick at the moment — there may be posts and links forthcoming — but right now I’m remembering one of the classiest and coolest catchphrases ever, Duke’s habitual goodbye to his audiences: “You are very beautiful, very sweet, and we do love you madly.” ♫

I don’t feel the need to repost everything on my Big Blog here, but I’m thinking that it might be useful occasionally to link to a tag that has some interesting material. For instance: climate.

This sincere interest in geoengineering and climate modification represents a broader shift in climate science from observation to intervention. It also represents a huge change for a field that used to regard any interference with the climate system — short of cutting greenhouse gas emissions — as verboten. “There is a growing realization that [solar radiation management] is not a taboo anymore,” Dan Visioni, a Cornell climate professor, told me. “There was a growing interest from NASA, NOAA, the national labs, that wasn’t there a year ago.”

At the highest level, this acceptance of geoengineering shows that scientists have seriously begun to imagine what will happen if humanity blows its goal of cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

I think this development is wholly welcome, and overdue.

Wendish Easter eggs – from Texas!

I rarely say that everyone should read something, but I’ll say that about this post by Mandy Brown.

Here’s a short post about one of the best Nichols & May comedy routines, which means, about one of the best comedy routines ever.

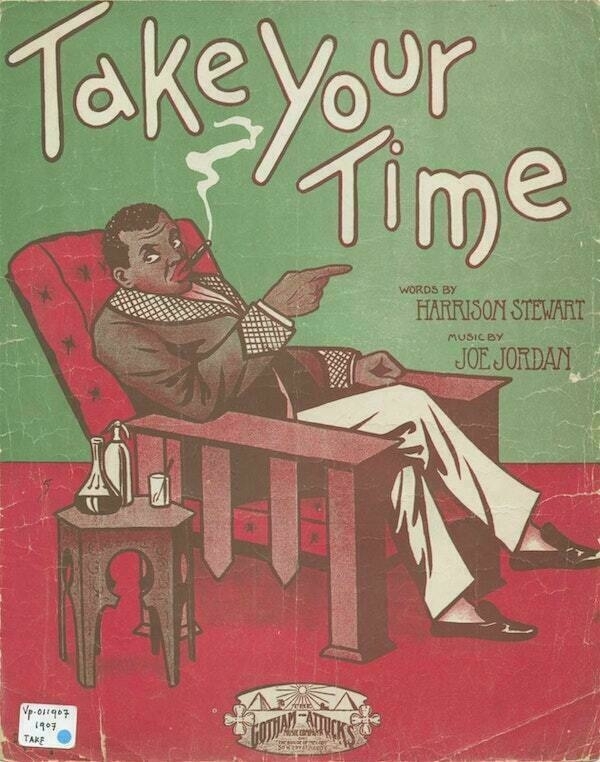

timing

People often talk about comic timing, but what does that mean, exactly? Well, here’s an example, from one of the best comedy routines ever: Elaine May as Bell Telephone (in several personae) and Mike Nichols as a self-confessed “broken man.” Watch it just for fun, because it carries a lot of fun.

Then watch it again and note pace: note that sometimes they rush, sometimes they pause, sometimes they talk over each other. It’s so musical — they’re like two jazz musicians who’ve been playing together forever and have mastered each other’s natural rhythms.

And then: not on the matter of timing, but rather delivery, you see the genius of Elaine May in three lines, one by each of the characters she plays:

- At 2:10: “Information cannot argue with a closed mind.”

- At 4:10: “Bell Telephone didn’t steal your dime. Bell Telephone doesn’t need your dime.”

- At 6:30, when Miss Jones is told that “one of your operators inadvertently collected my last dime”: “Oh my God.”

Absolute genius, I tell you.

I wrote about teaching Augustine’s Enchiridion.

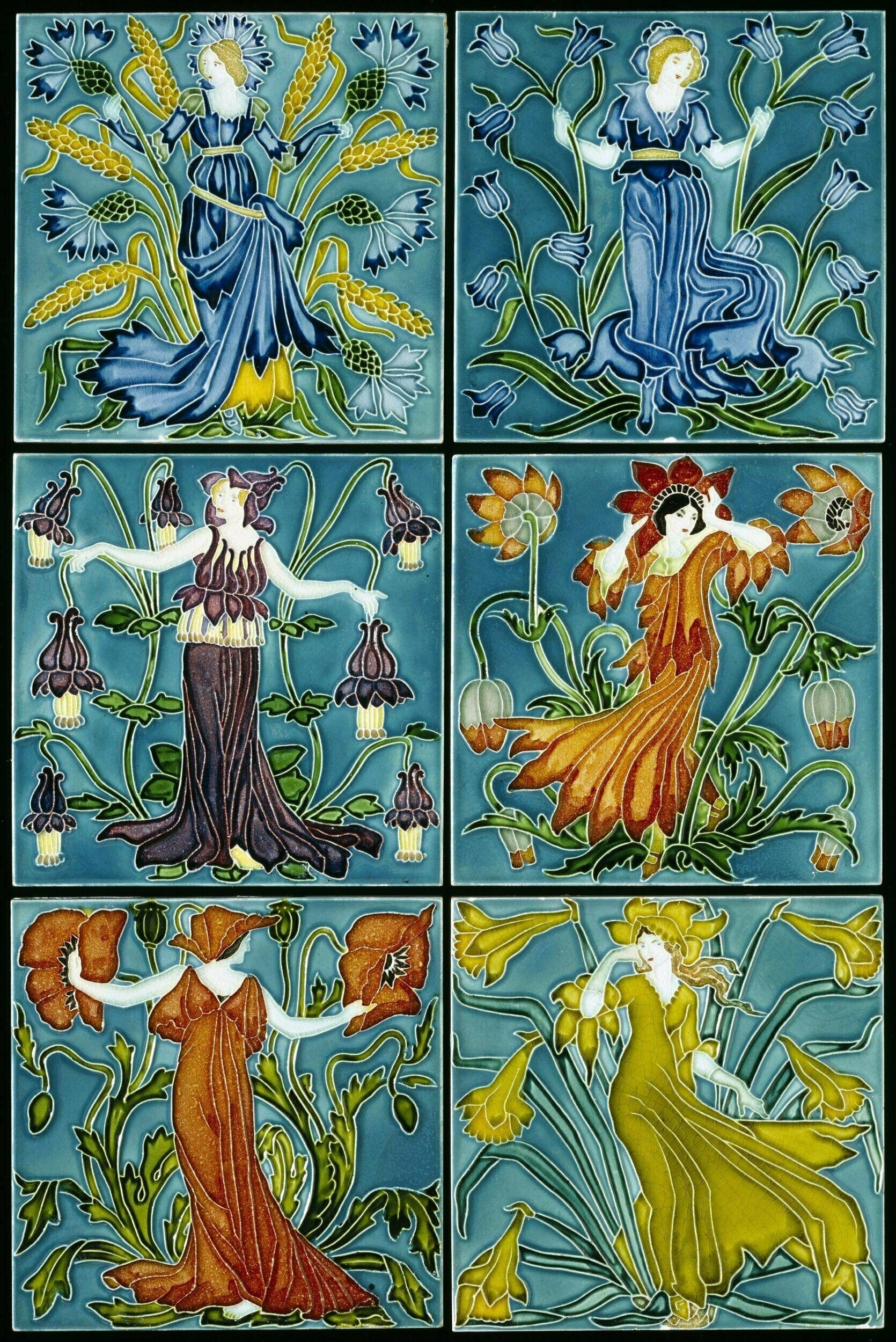

Walter Crane, Flora’s Train, tile panel, 1900-1901.

Class Notes: Enchiridion

Second in a series of reflections on what I’m teaching.

Late in his life, Augustine wrote his Enchiridion in response to a request from someone named Laurentius. What Laurentius wanted was a handy summary of Christian teaching that he could “always keep beside” him, to have ready when questions arose. He also wanted the handbook — for that is what enchiridion means — to contain refutations of other philosophies and theologies, but Augustine tells him that that kind of thing wouldn’t fit in a handbook, but rather would require several bookshelves full of books; and in any case, if one wishes to refute falsehoods, what one needs most of all is “to have a great zeal kindled in one’s heart.”

Augustine doesn’t say this, but in his day the best-known and most influential Enchiridion was that of Epictetus — which was, to be precise, a selection from Epictetus’s writings made and organized by a disciple of his named Arrian. It’s clear (if unstated) that Augustine thinks that Epictetus got it all wrong by starting from inadequate initial principles. Epictetus says that we need to begin by learning what is within our power and what isn’t. Augustine, by contrast, says that we have to begin by understanding that “the fear of the Lord, that is wisdom.” Nothing is within our power; everything comes from the Lord, and returns to him. (Exitus et reditus.) To fear the Lord is to worship him, and the “graces” by which we worship him are faith, hope, and love. Therefore a proper Enchiridion must be a guide to faith, hope, and love. Q.E.D.

And of course “the greatest of these is love.” For Augustine, human flourishing is never about assessing the scope of our power and adjusting our expectations accordingly. It’s about altering the direction and force of our loves, about turning away from self-love — ceasing to be incurvatus in se, uncoiling our self-constricted mode of being — and turning outwards, towards an ever-expanding love of God and neighbor.

We’re dealing with endless displays of Potemkin AI. As Molly White says, we “need to start keeping a list of all the times some big supposed display of bleeding edge technology turns out to just be A Guy.”

Class notes: Anarchy, Law, Pain

I’m thinking that this term, when I’m teaching a number of things I haven’t taught before, or haven't taught in a long time, I might use this blog to lay out some of the things I’m thinking about — not in a systematic or final way, but in what I hope will be a generative way (for myself, my students, and maybe even my readers). This will be the first such installment.

I would very much like to say that the anarchists in Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday aren’t really anarchists. I am, after all, at least anarchism-adjacent myself, and value the movement because of its peaceful and patient resistance to centralizing and domineering powers, especially, in our moment, the Power that’s sometimes called Technopoly. But, as Maya Jasanoff has pointed out, in 1881 the International Anarchist Congress officially adopted a strategy of “propaganda by deed” — i.e., terrorism.

Still, there is a distinction to make, and a learned constable, early in Thursday, makes it. When Gabriel Syme asks him “What is this anarchy?” He replies:

“Do not confuse it,” replied the constable, “with those chance dynamite outbreaks from Russia or from Ireland, which are really the outbreaks of oppressed, if mistaken, men. This is a vast philosophic movement, consisting of an outer and an inner ring. You might even call the outer ring the laity and the inner ring the priesthood. I prefer to call the outer ring the innocent section, the inner ring the supremely guilty section. The outer ring — the main mass of their supporters — are merely anarchists; that is, men who believe that rules and formulas have destroyed human happiness. They believe that all the evil results of human crime are the results of the system that has called it crime. They do not believe that the crime creates the punishment. They believe that the punishment has created the crime. They believe that if a man seduced seven women he would naturally walk away as blameless as the flowers of spring. They believe that if a man picked a pocket he would naturally feel exquisitely good. These I call the innocent section.”

“Oh!” said Syme.

“Naturally, therefore, these people talk about ‘a happy time coming’; ‘the paradise of the future’; ‘mankind freed from the bondage of vice and the bondage of virtue,’ and so on. And so also the men of the inner circle speak — the sacred priesthood. They also speak to applauding crowds of the happiness of the future, and of mankind freed at last. But in their mouths” — and the policeman lowered his voice — “in their mouths these happy phrases have a horrible meaning. They are under no illusions; they are too intellectual to think that man upon this earth can ever be quite free of original sin and the struggle. And they mean death. When they say that mankind shall be free at last, they mean that mankind shall commit suicide. When they talk of a paradise without right or wrong, they mean the grave.

“They have but two objects, to destroy first humanity and then themselves. That is why they throw bombs instead of firing pistols. The innocent rank and file are disappointed because the bomb has not killed the king; but the high-priesthood are happy because it has killed somebody.”

I think the constable is making an essential distinction, though I do not believe that either of his groups is actually anarchistic. Rather than two “rings” of anarchism, what the constable has described is the difference between libertines and nihilists.

That’s my view, anyway. What GKC wants to show in Thursday is that while people fear the “anarchists” who assassinate, even the assassins share with ordinary folks the belief that the world is in many ways bad and ought to be better — it is in that sense that they are “innocent.” We should be more concerned about those who randomly kill, randomly throw bombs, because at heart they reject the whole of Creation — they think that the world itself is not worth the candle, every law (natural law, moral law, whatever) is inevitably an insupportable tyranny, that nothingness itself is less bad than a world governed by law. Under law people suffer; and to end them, and ultimately end the world, is at least to end suffering.

Thus at the end of Thursday the “real anarchist” cries out,

I know what you are all of you, from first to last — you are the people in power! You are the police — the great fat, smiling men in blue and buttons! You are the Law, and you have never been broken. But is there a free soul alive that does not long to break you, only because you have never been broken? We in revolt talk all kind of nonsense doubtless about this crime or that crime of the Government. It is all folly! The only crime of the Government is that it governs. The unpardonable sin of the supreme power is that it is supreme.

Therefore, he says, “I am a destroyer. I would destroy the world if I could.”

Now, GKC rejects all of this. For one thing, as he says in Orthodoxy — the book he wrote immediately after writing Thursday — people wrongly think of Law as a cold dead hand imposing itself on Life:

All the towering materialism which dominates the modern mind rests ultimately upon one assumption; a false assumption. It is supposed that if a thing goes on repeating itself it is probably dead; a piece of clockwork. People feel that if the universe was personal it would vary; if the sun were alive it would dance. This is a fallacy even in relation to known fact. For the variation in human affairs is generally brought into them, not by life, but by death; by the dying down or breaking off of their strength or desire. A man varies his movements because of some slight element of failure or fatigue. He gets into an omnibus because he is tired of walking; or he walks because he is tired of sitting still. But if his life and joy were so gigantic that he never tired of going to Islington, he might go to Islington as regularly as the Thames goes to Sheerness. The very speed and ecstacy of his life would have the stillness of death. The sun rises every morning. I do not rise every morning; but the variation is due not to my activity, but to my inaction. Now, to put the matter in a popular phrase, it might be true that the sun rises regularly because he never gets tired of rising. His routine might be due, not to a lifelessness, but to a rush of life. The thing I mean can be seen, for instance, in children, when they find some game or joke that they specially enjoy. A child kicks his legs rhythmically through excess, not absence, of life. Because children have abounding vitality, because they are in spirit fierce and free, therefore they want things repeated and unchanged. They always say, “Do it again”; and the grown-up person does it again until he is nearly dead. For grown-up people are not strong enough to exult in monotony. But perhaps God is strong enough to exult in monotony. It is possible that God says every morning, “Do it again” to the sun; and every evening, “Do it again” to the moon. It may not be automatic necessity that makes all daisies alike; it may be that God makes every daisy separately, but has never got tired of making them. It may be that He has the eternal appetite of infancy; for we have sinned and grown old, and our Father is younger than we.

That’s one of my favorite passages in Chesterton, a vital re-conceiving of the meaning of repetition. But it’s not the point he chooses to emphasize in Thursday. What turns out to be the whole point of that novel is the re-conceiving of the relationship between law and suffering. The policemen, i.e. the upholders of the Law, are said by the Accuser to be safe, to be free from fear and pain. But precisely the opposite is true. As Syme says to that Accuser, “We have been broken on the wheel.” It is a hard calling to become strong enough to exult in monotony — and, while doing so, to restrain the destructive impulses of those who believe that repetition is an infringement on their freedom, an imposed pain.

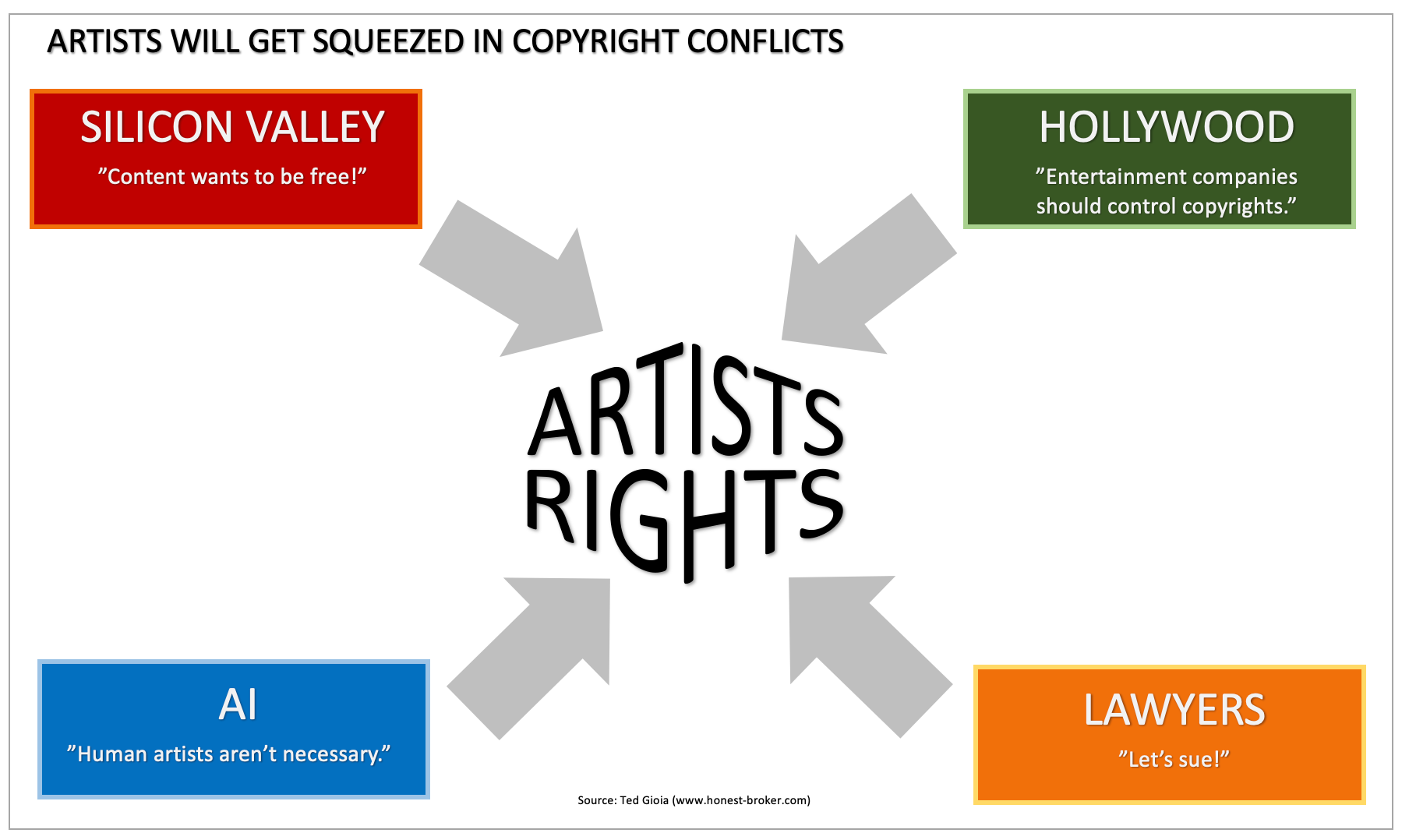

Ted Gioia’s “Nine Ugly Truths about Copywright” is brilliant.