With the Mac turning 40, a question going around is: What was your first Mac? Mine was … the first Mac, in all its 128k glory. Bought (with a bank loan arranged by my mom, who worked in a bank) in early 1985. I wrote my dissertation on it; everything I have ever published was written on a Mac.

placing bets

The last four of Ted Gioia's seven hypotheses about meaningful progress:

4. The discourse on progress is controlled by technocrats, politicians and economists. But in the current moment, they are the wrong people to decide which metrics drive quality of life and human flourishing.

5. Real wisdom on human flourishing is now more likely to come from the humanities, philosophy, and the spiritual realms than technocrats and politicians. By destroying these disciplines, we actually reduce our chances at genuine advancement.

6. Things like music, books, art, family, friends, the inner life, etc. will increasingly play a larger role in quality of life (and hence progress) than gadgets and devices.

7. Over the next decade, the epicenter for meaningful progress will be the private lives of individuals and small communities. It will be driven by their wisdom, their core values, and the courage of their convictions — none of which will be supplied via virtual reality headsets or apps on their smartphones.

The ongoing existence of this here blog is based on almost exactly these assumptions. It’s a bet that people want what’s best about the world.

FWIW

I’ve written before about how my own history as a fabulist makes me reflexively skeptical about certain kinds of stories that people tell. But it’s not my history as a fabulist, it’s rather my belief in original sin that makes me skeptical of one particular kind of story: the “Doing this hurts me but darn it I simply must stand up for my principles” story — which is the tale that a number of former Substackers are telling these days. “Substack is great for me but I simply can’t be on the same platform with all these Nazis” — though as many people have pointed out, Substack has maybe half a dozen Nazis among its zillions of users, and none of the platforms these people are decamping for are Nazi-free either.

Here’s what I believe: This has absolutely nothing to do with Nazis. The purpose of the campaign is not to expel Nazis from Substack but to create a precedent. If Substack said “Okay, the Nazis are gone, the response would not be “Thanks!” It would be, “Cool, now let’s talk about Rod Dreher.” And then Bari Weiss, and then Jesse Singal, and then Freddie DeBoer, etc. etc. The goal is not to eliminate Nazis; the goal is to reconstitute the ideological monoculture that Substack, for all its flaws — it’s not a service I would ever use —, has effectively disrupted.

head start

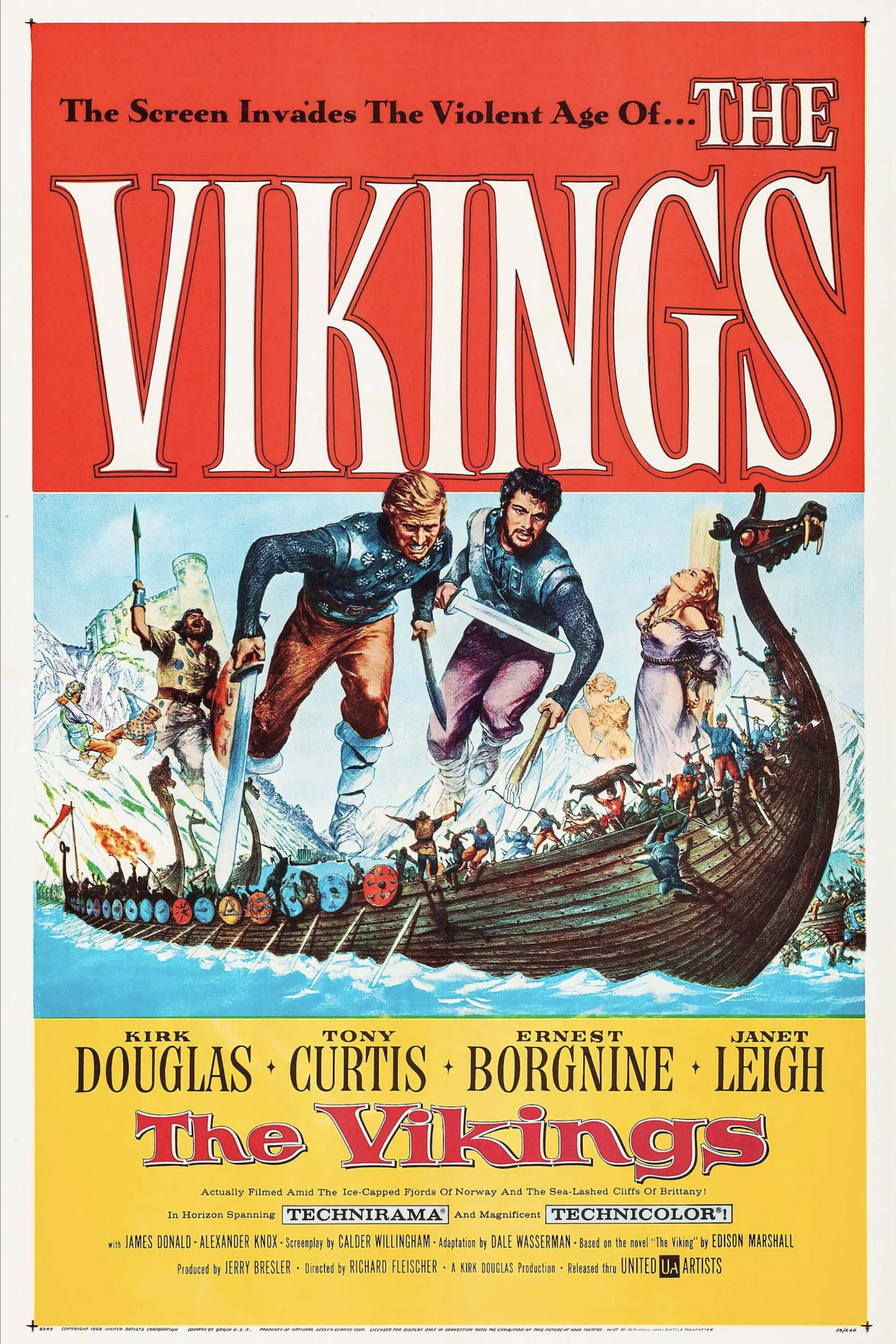

The Vikings was the first movie I ever saw — not in a standard movie theater, but some years after its release, at a drive-in. I remember being at once bemused and excited by the rituals of finding a parking place, hanging the speaker over the car door .. and the movie itself? I adored it. What four-year-old wouldn’t?

I also remember quite clearly the first movie I saw in a proper movie theater, not too long after I saw The Vikings. It was this:

So what I’m saying is that I had a good start on my movie-watching career.

Things got even better a few years later when my ne’er-do-well uncle — a ladies’ man, a snappy dresser, a driver (and occasional seller) of exotic automobiles — decided to take his 12-year-old nephew to the movies, in fact to a double feature. And what were those movies? Why, Dirty Harry and The Wild Bunch, of course. Food for the spirit of a growing boy.

Why don’t Arsenal win every game 5-0? It seems such an obvious solution to their problems. ⚽️

Noteworthy, I think, that neither this Becca Rothfield review of The Geography of the Imagination nor John Jeremiah Sullivan’s introduction to the new edition give you any real sense of what it’s like to read Guy Davenport. Nothing does that except … reading Guy Davenport.

In which I explain what I did on the first day of a new class – and then go on a wild-eyed rant against Spotify.

Systematic theology? I don’t need no stinkin' systematic theology – I have Joe Mangina’s “Figural Graffiti,” in forty-nine rhymed couplets. Seriously, when people ask me what my theology is, I’ll show them this.

ADD revisited

On the first day of my Christian Renaissance of the Twentieth Century course — mentioned here — I played for my students a few minutes of the first movement of Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto. We paused to talk a bit about the musical language of late Romanticism, about Rachmaninoff’s gift for lush melody, etc. Then I played them this:

Hard to believe it was composed by the same man, isn’t it? But (I suggested) that’s the difference between a young Russian composer in 1901 — he wrote that concerto when he was 27 — and a middle-aged Russian composer living through overwhelming political turmoil and world war. In time of desperate need Rachmaninoff, not a churchgoer, turned to the liturgical and musical inheritance of Orthodoxy to make sense of his world, to begin the long healing that would be necessary.But the healing didn’t happen. Russia was further broken by the war, then entered the long nightmare of Bolshevik rule, and Rachmaninoff became one of many exiles. In some ways he never recovered from this experience. Many years later, while living in California, he lamented his inability to compose music: “Losing my country, I lost myself also.” (Exile versus homecoming — one of the themes of my class.) But the All-Night Vigil remains, for me, one of the transcendent works of music. Rachmaninoff himself thought it perhaps his best composition.

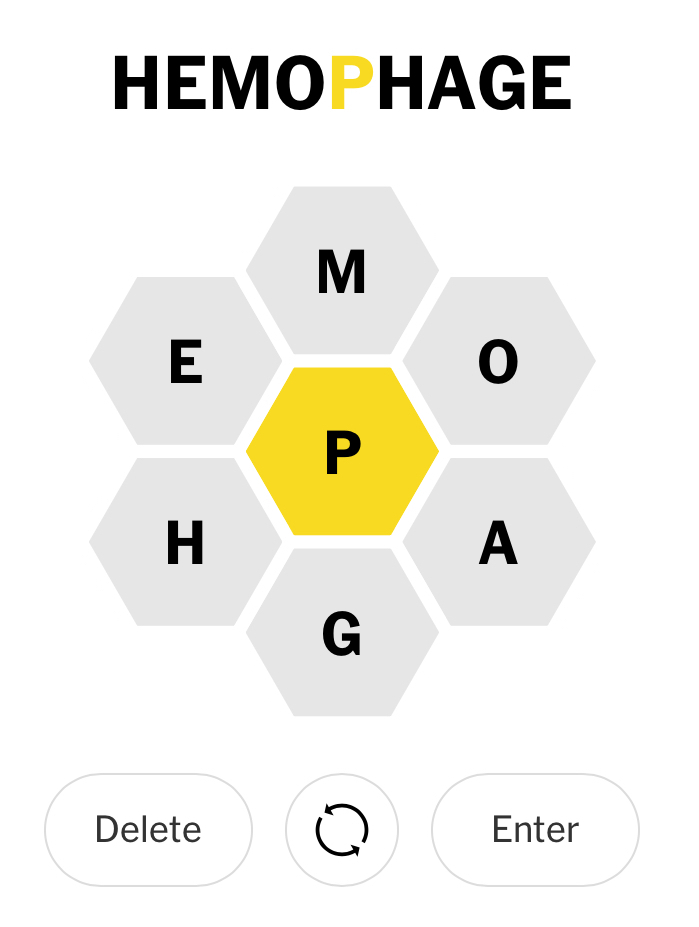

But I have another motive in having my students listen to this music, which is to get them to listen to music. People these days, especially but not only young people, have music on all the time, but that’s not the same as listening to it. Indeed, as Ted Gioia and Damon Krukowski have documented repeatedly, Spotify — and pretty much all my students use Spotify — positively wants its users to unlisten, to merely have music on in the background, in part because that allows the company to shift from actual music made by human musicians to AI-generated neo-Muzak. The tiny amount that Spotify pays musicians is already shameful, but it’s too much for a company that doesn’t have a workable business model, so the best way to limit costs is to cut human musicians out of the game altogether. But this will only work if Spotify can habituate its users to empty, mindless schlock, made up of endless variations on the same four chords.

I’ve made it a classroom practice in the last year or so to indulge in theatrical rants against Spotify, which is fun for me and for my students. They argue with me and I denounce them, all in good humor. But for all the smiles, I am quite serious. Spotify is creating in millions and millions of its users a new kind of Attention Deficit Disorder, not one that has them jumping from one thing to another, but rather has them in a kind of vague trance state. Spotify is like soma from Brave New World in audio form. And to be in such a state is to experience a deficit of attention, an inability genuine to attend to what one is hearing.

So one of the things I am doing in this class, and will be trying in other classes, is to get my students to spend five minutes listening to music. I forbid digital devices in my classes, so they just have their books and notebooks in front of them — they can of course be distracted from the music, but it’s not automatic, not easy. If listening is the path of least resistance, then maybe they’ll listen. I’ve started with five minutes, but I hope to work our way up to longer pieces. My dream — and alas, it is but a dream — is, one Holy Week, to sit together with my students and listen to the single 70-minute movement that is Arvo Pärt’s Passio.

This $100 million gift to Spelman College ought to be praised to the skies. The megarich need to direct their money towards institutions that can seriously benefit from it. Giving money to Harvard is like giving money to Microsoft.

John Gruber – aka @gruber – on a theme I discussed yesterday, the difference between Apple’s view of the Mac platform versus iOS/iPad: “Developer uncertainty regarding the viability of selling Mac software is the last thing needed for a platform that is already facing a dearth of new original native software. Apple doesn’t have to make a platform-destructive money-grab policy change to ruin the Mac. They can ruin it simply by planting the seed of doubt that they might.”

Robin Sloan says of me, “Alan can make anything sound terrific, when he loves it,” which is one of the best things anyone has ever said about me. I’m not even sure it’s a compliment, but I like it anyway. (And I hope Robin reads Cahokia Jazz, which really is wonderful.)

What Dracula is

If, as some think, deepfakes will become undetectable, that just might force a long-overdue reckoning with our reliance on online “information” and “evidence.”

I added some links, fixed some bad links, and generally updated things at my home page.

I think DHH is right about Apple.