Yet another really nice one from Adrian Vila.

Mark Hurst: Marc Andreessen is right – love doesn’t scale.

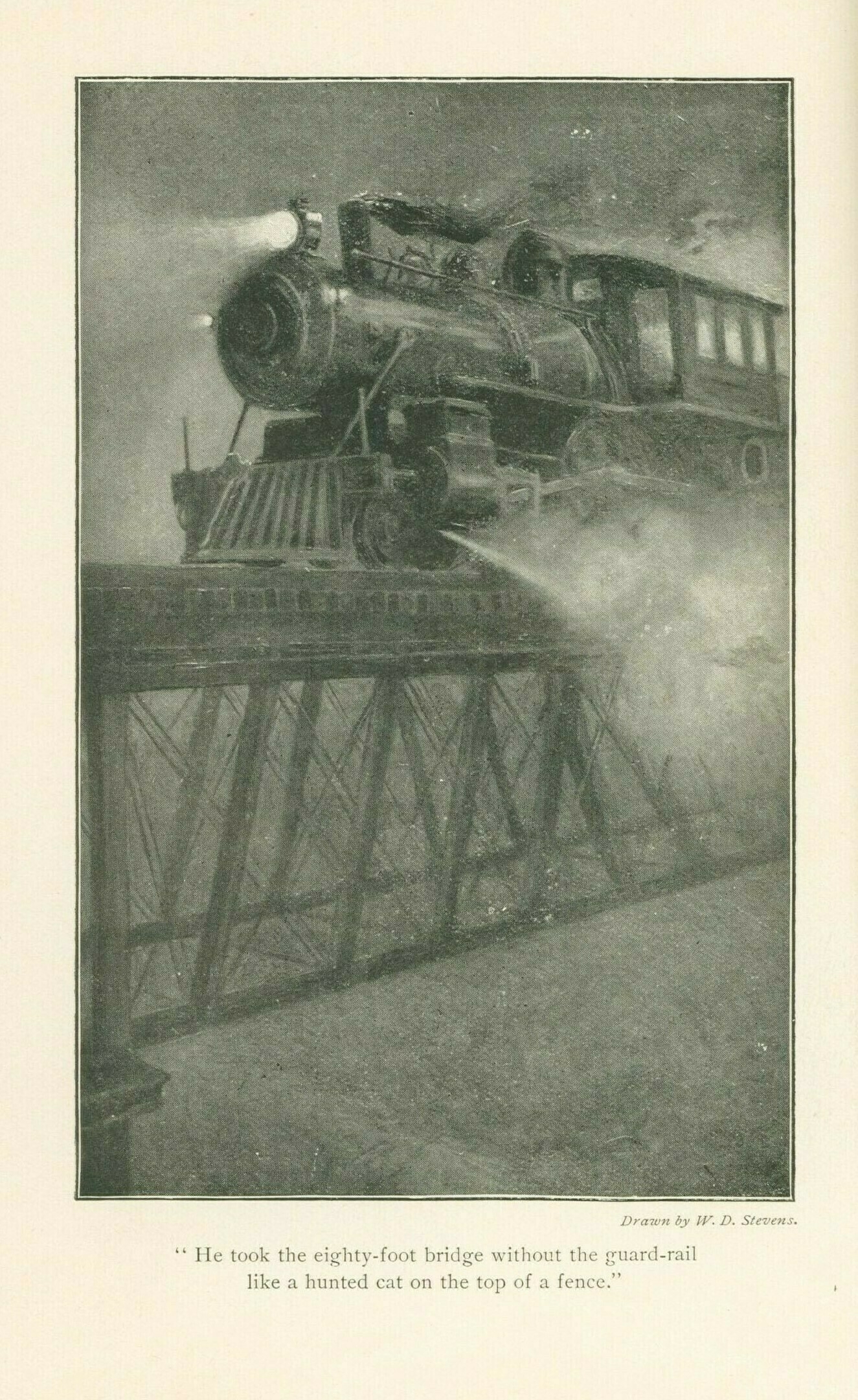

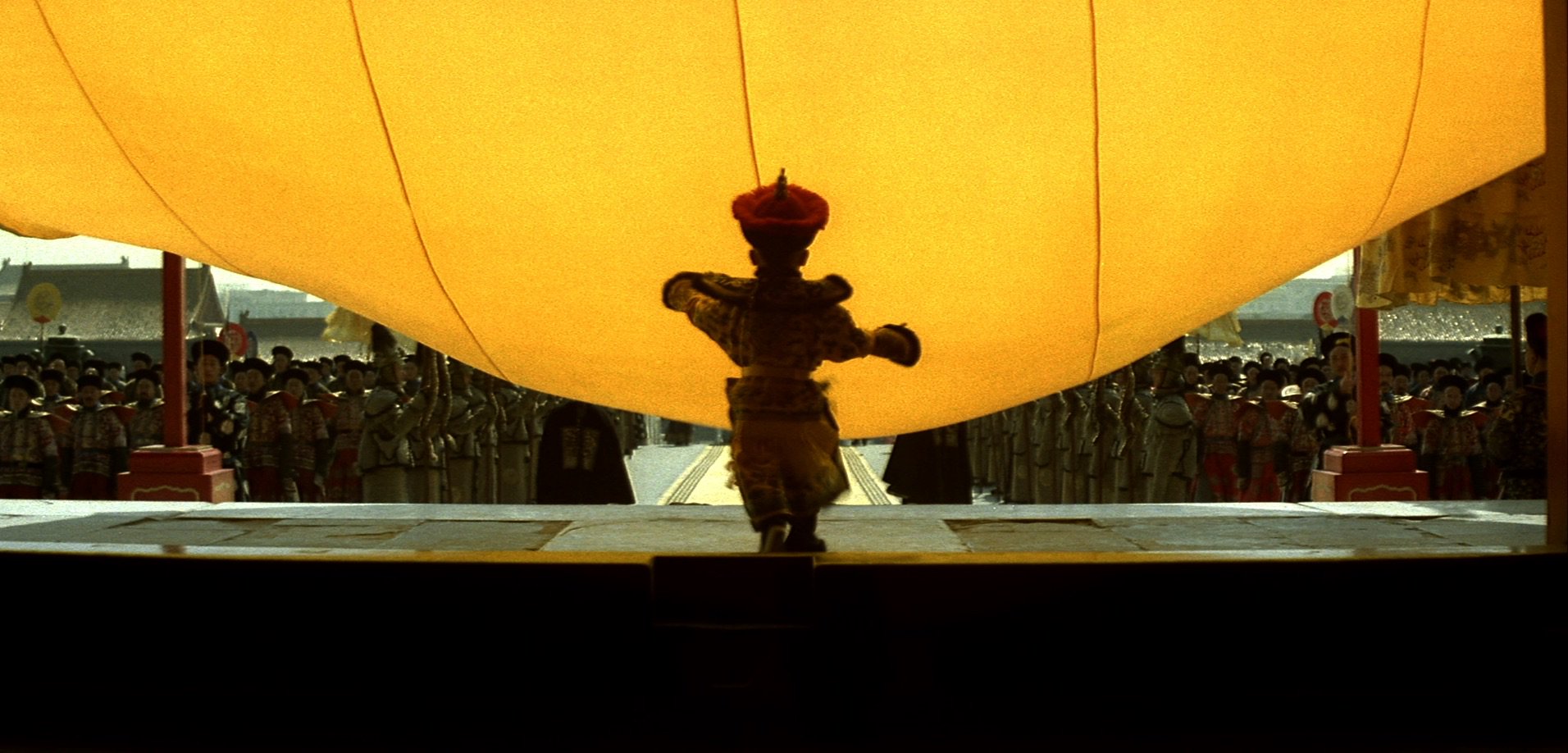

Bertolucci

Some years ago I read an article about sociopathy – I don’t remember the author or where it appeared, but I do recall the description of a boy who began to show signs of sociopathy from an early age. Once, as he and his parents gathering with family and friends at a house that had a swimming pool, a younger cousin, a toddler or barely older, fell into the pool at a moment when no one was paying attention – just this boy. As the toddler flailed helplessly in the water, the boy watched. He didn’t try to help, or even call for help; he just watched. Eventually an adult noticed, and rescued the small one. When the boy was asked why he didn’t do anything but watch a child drowning, he replied that he had wanted to see what happened.

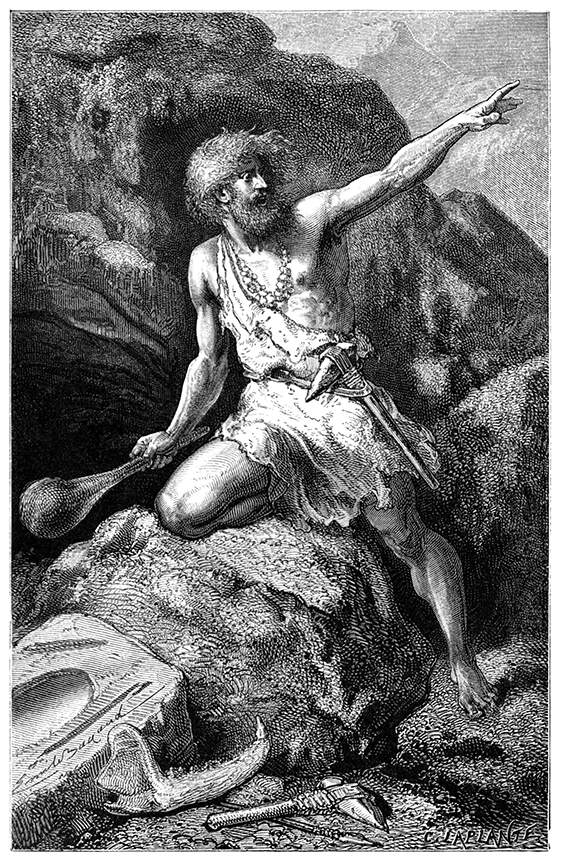

I think about that boy when I watch the films of Bernardo Bertolucci. Maybe that’s not fair; it’s hard to say. Dramatic films are just that, dramatic – their makers do not provide authorial commentary on the action. They portray, we judge. So I am not saying that Bertolucci was a sociopath; I am instead saying that his movies feel to me that he’s asking me not to empathize, but to watch. And because his images are so compelling, it’s hard not to watch.

Like Antonioni, Bertolucci tends to make movies about lost souls. But when I’m watching L’Avventura or La Notte, I feel that the director has compassion for these souls in their lostness, and is inviting, even encouraging, me to have compassion for them also. By contrast, Bertolucci seems to be setting up his camera at the end of the pool and simply pointing it at the drowning child.

I wrote a mid-season report on Arsenal. ⚽️

Arsenal mid-season report

This side is not a contender for the league title — not even close. At this point I'm not confident that they can hold on to a Champions League place: they're far behind Man City and Liverpool, noticeably behind Aston Villa, and probably behind Spurs (though Spurs' lack of depth could haunt them in the months to come).

Because Arsenal are so toothless in attack, the temptation will be to think that they have to sign a striker in the January transfer window. But (a) they will almost certainly have to overpay dramatically for anyone worth having; (b) strikers rarely settle immediately into a new side — they need time to get adjusted to new teammates and a new style of play; and (c) there's not a game-changing striker available. Succumbing to this temptation would lead to heartache — but I fear that that's what the club will do.

It's true that Arsenal don't have a top goal-scorer, but that's not their primary problem. After all, they had a fine season last year while spreading the goals around quite widely. Their primary problem is this: Arteta has wildly over-reacted to the way that last season ended. Last season's side was a high-energy, high-risk, excitable, even manic show. Every time they won a game they shouted and leaped into one another's arms, and the game's self-appointed Celebration Police tut-tutted and said, in unison, "They act like they won the league.”

It seems obvious that the club's leadership decided that this emotional intensity caused the team to run out of gas late last season. So they — or maybe it's just Arteta — decided to take a different approach this season.

The first move in this direction was eminently sensible and has been quite successful: signing Declan Rice means that the team now has a physically commanding and highly intelligent defensive midfielder to play in front of the two excellent centerbacks, which means that Arsenal are very difficult to score against.

The second move was to replace the most excitable member of last year's side, the keeper Aaron Ramsdale, with the calmer and somewhat more technical David Raya. This decision, I think, has been as bad as the signing of Rice has been good. It's not that Raya has performed poorly; he hasn't. He's been about as good as Ramsdale, though not noticeably better as distribution (which is supposed to be his big advantage). The problem is that Raya is a pretty quiet and undemonstrative guy, while Ramsdale was the emotional leader of last year's side. He was the spark plug that ignited the fuel, and without him the team seems to be playing mechanically and joylessly. (The other really fiery player from last year’s side, Granit Xhaka, now plays in the Bundesliga. The club might do better to bring Xhaka back than sign an overpriced striker.)

In Sunday's mostly listless — after the first ten minutes anyway — performance against Liverpool, the crowd at the Emirates was virtually silent. Watching on TV, you could hear everything said on the pitch and sideline through most of the match. At one point Martin Odegaard — a fine captain, about whom I have nothing bad to say — tried to rouse the crowd, but they responded halfheartedly. This was, to put it mildly, not a problem last year. If the team is excited and energetic the crowd will be too; if not, not.

The player who has suffered most from this new emphasis on restraint and discipline has been Gabriel Martinelli — who is a shadow of his last year’s self. But I think everyone’s less intense this year, and other teams are just outworking them.

When the team has had energy this season, it's been negative energy, generated by Mikel Arteta's constant whining about officiating. Indeed, I suspect that Arteta's complaining has hurt the team’s spirit as much as the tamping down of enthusiasm.

Can Arteta make the necessary adjustments both to his tactics and his mood? Can he reignite the fire from last season and become a more positive figure, keeping in mind that he still has a very young side, with many players who are highly influenced by his example? Maybe; he seems to be an exceptionally stubborn person, but I think the organization as a whole is strong and that there’s a good opportunity here at the brief winter break to part with some bad habits. I think we just have to hope that he learns from experience and admits his mistakes. I wish I had a better answer than that.

On going beyond the SCT — the Standard Critique of Technology.

beyond the SCT

My 2021 essay on “cosmotechnics” begins thus:

In the 1950s and 1960s, a series of thinkers, beginning with Jacques Ellul and Marshall McLuhan, began to describe the anatomy of our technological society. Then, starting in the 1970s, a generation emerged who articulated a detailed critique of that society. The critique produced by these figures I refer to in the singular because it shares core features, if not a common vocabulary. What Ivan Illich, Ursula Franklin, Albert Borgmann, and a few others have said about technology is powerful, incisive, and remarkably coherent. I am going to call the argument they share the Standard Critique of Technology, or SCT. The one problem with the SCT is that it has had no success in reversing, or even slowing, the momentum of our society’s move toward what one of their number, Neil Postman, called technopoly.

The basic argument of the SCT goes like this. We live in a technopoly, a society in which powerful technologies come to dominate the people they are supposed to serve, and reshape us in their image. These technologies, therefore, might be called prescriptive (to use Franklin’s term) or manipulatory (to use Illich’s). For example, social networks promise to forge connections – but they also encourage mob rule. Facial-recognition software helps to identify suspects – and to keep tabs on whole populations. Collectively, these technologies constitute the device paradigm (Borgmann), which in turn produces a culture of compliance (Franklin).

The proper response to this situation is not to shun technology itself, for human beings are intrinsically and necessarily users of tools. Rather, it is to find and use technologies that, instead of manipulating us, serve sound human ends and the focal practices (Borgmann) that embody those ends. A table becomes a center for family life; a musical instrument skillfully played enlivens those around it. Those healthier technologies might be referred to as holistic (Franklin) or convivial (Illich), because they fit within the human lifeworld and enhance our relations with one another. Our task, then, is to discern these tendencies or affordances of our technologies and, on both social and personal levels, choose the holistic, convivial ones.

The point of this essay was to say that (a) the SCT is absolutely correct and (b) there’s no point in continuing to restate the SCT, even if you shift the terms around a bit or employ alternate ones. (For instance, Paul Kingsnorth talks about “the Machine” — but it’s precisely the same set of concepts and critiques.)

That essay, for me, marked the end of a decade or so of articulating my own version of, or elaborations on, the SCT. For much of that decade I wrote about Technopoly’s demands on our attention, and insisted that we can attend otherwise.

But how many times can you say that?

Since I wrote that essay I have (mostly) refrained from saying “We should attend to things other than those Technopoly wants us to attend to” and instead have tried simply to attend to other things. In other words: I’ve given up on making arguments about where our attention should go – not primarily because such arguments are useless, though they may well be, but because I have made them already – and have instead pursued demonstration. Hey, look at this fascinating thing I’ve been looking at. That’s what I’ve been doing since 2021, and it’s what I plan to keep doing.

Basically, I’m just a simple caveman; your modern world confuses and frightens me. But one thing I do know: That I ain’t buying what Technopoly (or the Machine, or whatever you want to call it) is selling.

Kashmir Hill: “My black clamshell of a phone had the effect of a clerical collar, inducing people to confess their screen time sins to me. They hated that they looked at their phone so much around their children, that they watched TikTok at night instead of sleeping, that they looked at it while they were driving, that they started and ended their days with it.”

The Next Turn of the Wheel

This is the novelist Janet Burroway, writing about her experience making a fifth edition of a textbook for creative writing classes:

Unusually, this time around my publisher asked for no refreshing of my ideas, no major swaths of rewriting, only that I conform to the new sensibility. I was asked to change the binary “he/she,” for example, and to substitute they as a neutral nonbinary, or to refashion the sentence so that the plural made sense. The latter was often easy. The former not so much.

My instructions suggested that even if I was positing a hypothetical stage scene, I should not designate an actor as male or female. I was asked not to say “pregnant woman” since trans men can sometimes give birth. I was asked to substitute “home” where I had said “house,” on the grounds that some people don’t have houses. (What of those who have a house but no home?) I was to add “or caregiver” to every mention of mother, father, or parents. “Heroine” and “hero” are out. “God” should not be referenced, since different people have different gods, or none. Likewise, “Him” should not be capitalized. Noah’s Ark should not be mentioned, since non-Bible-savvy students might not know the story. “First year” must be used instead of the sexist “freshman.” “Foreign” and “foreigners” are offensive in any context. “Nerd,” “tribal,” “naïve,” “’hood,” “ugliness,” and “race” should not be said. Don’t mention shame, straitjacket, suicide, Donald Trump, or Kevin Spacey!

To virtually all of these admonitions, even when I thought them misguided or silly, I agreed. My own prose was not after all sacred. But when it came to the imaginative prose of other writers, trouble began.

Trouble began because whenever those authors — many of whom are racial or sexual minorities — had written, or simply had made their characters say, something deemed offensive, then Burroway was instructed to delete that example of their writing and find another example, one that could not possibly offend any member of any protected group. The previous edition of her textbook had quoted one memoirist describing the nasty names he was called as a child, so she was asked to remove that quotation and choose another (properly sanitized) one that avoids potential harm to an imaginary reader.

Burroway doesn’t say this, but these principles, consistently followed, would prevent people who have suffered racism, sexism, homophobia, classism, and any other form of trauma from writing honestly about their experience, since such honest writing might perpetuate the effects of racism, sexism, homophobia, etc. etc. Every offense is The Offense That Dare Not Speak Its Content.

As I read, I was reminded of a book I wrote about many years ago, Ruth Bottigheimer’s The Bible for Children. Here’s a passage from my essay:

Problems usually arise for the makers of children’s Bibles not because they are uncertain how to interpret a story, but rather because they do not know how bluntly they dare relate that story. No one questions the evil of David’s adultery with Bathsheba; but how do you explain that adultery to children who may not yet know anything about human sexuality? Some writers, Bottigheimer shows, said that David “took another’s wife,” leaving the concept of “taking” ambiguous. Others (especially in the nineteenth century) made no reference whatsoever to the sexual nature of the sin: David committed “a shocking offense,” one said, while another noted still more vaguely that “he grew tyrannical and began to sin.”

But those were Bibles for small children. Burroway’s publisher (like many others) thinks that university students are children; maybe that we all are.

I happened to read Burroway’s depressing account immediately after reading a wonderful essay by Witold Rybczynski on ornament in architecture. Rybczynski describes

a lecture given in Vienna on January 21, 1910. The venue was the Akademischer Verband für Literatur und Musik, an association of university students and their friends that organized avant-garde concerts by the likes of Arnold Schoenberg and exhibits by young firebrands such as Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele. The lecturer that January evening was not so young, a 39-year-old Moravian-born architect named Adolf Loos, but he was definitely a firebrand. He titled his talk “Ornament und Verbrechen” (Ornament and Crime), and his theme, encapsulated in the title, was that ornamentation was both uneconomical and morally wrong; therein lay the crime. The lecture, which was actually more like an extended harangue, consisted of stirring if unproven pronouncements: “The evolution of culture is synonymous with the removal of ornamentation from objects of everyday use” — an assertion difficult to prove, since in 1910 both machine tools and steam locomotives often incorporated ornament. Nevertheless, to Loos, ornament was a throwback to a primitive time and had no place in the modern world. “Ornament is wasted labor and hence wasted breath,” he declared. “That’s how it has always been.” One can hear the outrage in his voice.

What do Adolf Loos and Janet Burroway’s publisher have in common? The belief that one can achieve virtue through omission and excision. This is the belief shared by all forms of purity culture — and purity culture always leads to katharsis culture, that is, the practice of cleansing yourself, restoring your purity, by casting out the unclean thing.

But what if that’s not how virtue works? What if after having cast out every unclean thing you can find you just end up in the foul rag and bone shop of your own heart? What then?

That’s why these periods of desperate and manic katharsis always burn themselves out — why Robespierre ends by executing the executioner. And when they’ve done all they can do, they are succeeded by a bacchanal, an era of pseudo-festive delight in transgression. Our culture oscillates between “cast out the unclean thing” and “let us sin the more that grace may abound” — that is, between legalism and antinomianism, the very pairing that St. Paul in his letters is always trying to subvert.

Paul is the greatest of psychologists: he knows that human beings perfectly well understand legalism, which they rename “justice,” and perfectly well understand antinomianism, which they rename “freedom.” What we can’t understand is the grace of God.

So we keep turning our simple wheel. Today it's justice prized and freedom despised; tomorrow will be the opposite. The bacchanal is coming. Get ready.

Strange sights in the pre-dawn fog.

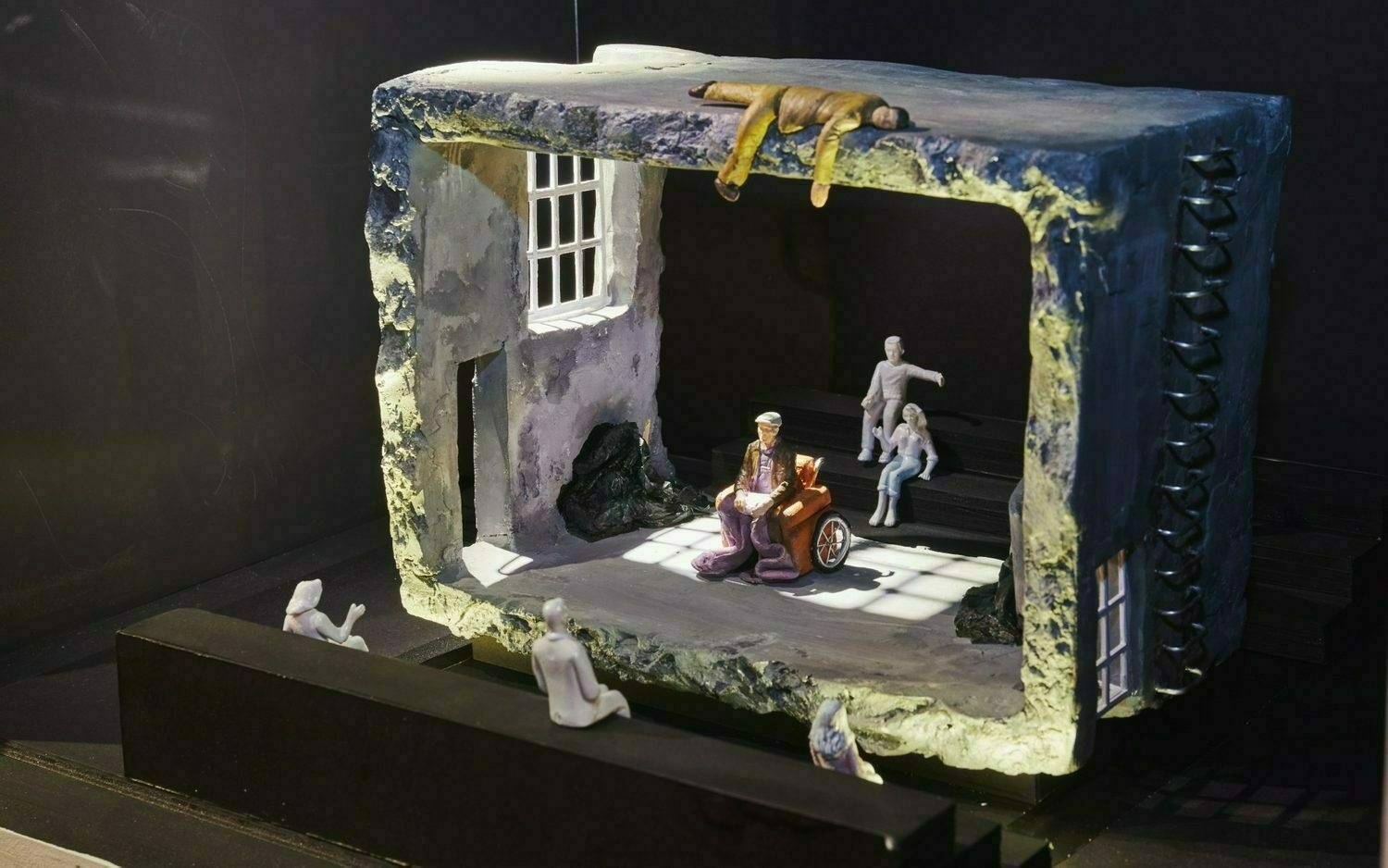

Model box for ‘Endgame’ by Samuel Beckett, designed by Tallulah Caskey, for the National Theatre, London

Mark Helprin: “Tending a fire enforces a sense of patience and tranquility. In that way it is like sailing a boat. You’re engaged by it and trapped by it; fire is captivating. Your time is captured so you have enforced idleness. Like music, it somehow coordinates the rhythms in your brain, or in your soul. It clears the air. Enforced idleness is the way I want to live. I want to be a prisoner of things that make me stop still.”

The Real Value of a Catholic Modernity

In 1996 the philosopher Charles Taylor delivered a lecture – later to be published with several responses – called “A Catholic Modernity?” But do you know what the truly essential value of a Catholic modernity is? It was a Catholic modernity that defeated Dracula.

The Catholic elements of the story are memorable. Most readers will readily recall Dracula shrinking back from a crucifix thrust in his face; many will also remember the consecrated Hosts with which Dr. van Helsing “sanitises” the big boxes filled with Transylvanian earth in which Dracula plans to hide himself; or the moment when, in the Transylvanian wilderness near the Count’s castle, he crumples more Hosts into powder that he uses to form a protective circle around Mina Harker.

But Dracula’s biggest mistake is to enter the world of technocratic modernity.

We know why he does it: he lives in a sparsely populated backwater, whereas London is the largest city in the world and offers an endless supply of victims: victims he can kill and victims he can make into an army of the Undead. But this man of the early modern era can only enter London by obeying the procedures of modernity, which is to say, by acquiring a modern identity. As James Scott has taught us – and this is a theme I pursue in an essay nominally about Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple – the modern state makes people legible. And it is because Dracula becomes legible that he is thwarted, discovered, and killed.

Because Dracula cannot move freely in the daytime, he must have a place of refuge and safety while the sun shines. So he needs both the aforementioned boxes – temporary coffins – and homes (“mansions”) or warehouses in which to keep them. To buy these things he needs money, which he has plenty of; but he also needs to follow the administrative procedures of the modern capitalist state. He can’t ship anything without giving a name and an address, and – more important to the story – without employing people, from real estate agents to plain old carters, who keep records. Our heroes’ long pursuit of Dracula is largely a matter of tracing the written records of everything Dracula does in England. Note also that the enemies of Dracula coordinate their plan of action with reference to the sequence of events that they have recorded using typewriters and phonographs. (Dracula is the first novel featuring voice memos.)

Dracula doesn’t understand this world. At one point he breaks into Dr. Seward’s office to destroy the handwritten journals and letters that document his evil deeds. But what he doesn’t know is that Mina Harker has made typewritten copies of it all. Dracula is like the Bishop of London in the sixteenth century who bought and burned copies of Tyndale’s New Testament, not realizing that Tyndale could use the proceeds to make more copies.

And modernity reigns not just in England: even in eastern Europe the pursuers are greatly aided by Mina’s knowledge of when the trains run — and by telegraphs they receive from London. Railway timetables, telegraphs, phonographs, typewriters, invoices, bills of lading, double-entry bookkeeping: these are the instruments by which Dracula’s pursuers draw their net around him. (And money – let’s not forget money. As Mina Harker writes in her journal, “Oh, it did me good to see the way that these brave men worked. How can women help loving men when they are so earnest, and so true, and so brave! And, too, it made me think of the wonderful power of money!”)

Dracula’s own powers – superhuman strength, the control of local weather, the ability to summon and direct brute creatures – cannot match the powers of his Enemy. And that Enemy is not Dr. Van Helsing or Jonathan Harker or any of the other people who chase him, but rather technocratic modernity itself — supplemented and strengthened by the spiritual technologies of the Church, that is, material objects sanctified for holy purposes.

Poor Dracula, he never had a chance – not against the double-reinforced power of a Catholic Modernity.