Christmas coma setting in.

Lo how a rose

Merry Christmas!

A post on George MacDonald and Christmas — though be warned, this one’s a bit of a tearjerker.

Christmas gifts

In introducing the writings of George MacDonald, C. S. Lewis made a fascinating point which can only be quoted at length:

What [MacDonald] does best is fantasy — fantasy that hovers between the allegorical and the mythopoeic. And this, in my opinion, he does better than any man. The critical problem with which we are confronted is whether this art — the art of myth-making — is a species of the literary art. The objection to so classifying it is that the Myth does not essentially exist in words at all. We all agree that the story of Balder is a great myth, a thing of inexhaustible value. But of whose version — whose words — are we thinking when we say this?

For my own part, the answer is that I am not thinking of anyone’s words. No poet, as far as I know or can remember, has told this story supremely well. I am not thinking of any particular version of it. If the story is anywhere embodied in words, that is almost an accident. What really delights and nourishes me is a particular pattern of events, which would equally delight and nourish me if it had reached me by some medium which involved no words at all — say by a mime, or a film. And I find this to be true of all such stories. […]

Most myths were made in prehistoric times, and, I suppose, not consciously made by individuals at all. But every now and then there occurs in the modern world a genius — a Kafka or a Novalis — who can make such a story. MacDonald is the greatest genius of this kind whom I know. But I do not know how to classify such genius. To call it literary genius seems unsatisfactory since it can coexist with great inferiority in the art of words… . Nor can it be fitted into any of the other arts. It begins to look as if there were an art, or a gift, which criticism has largely ignored.

Lewis is prompted to this reflection in part by the fact that MacDonald was not a very good stylist — his prose is often clunky or awkward. But the myths he made were to Lewis extraordinarily powerful. I think that Lewis is right not only about Macdonald but also in his more general point, and that the phenomenon deserves more reflection that it has received.

I may come back to this intriguing idea some day, but I only mention it now because it gives me license to tell briefly, in my own words, one of MacDonald’s stories, “The Gifts of the Child Christ.”

The story centers on a six-year-old girl named Sophy — “or, as she called herself by a transposition of consonant sounds common with children, Phosy.” Phosy’s mother died giving birth to her and her father has recently remarried. He had been in various ways disappointed with his first wife and now he is well on his way to becoming disappointed with his second wife; and he neglects Phosy because she reminds him too much of the wife whom he had lost, and who had not made him happy.

Phosy’s stepmother is pregnant and that means that Phosy is ignored even more than usual; but she doesn’t seem to expect anything else. When at church with her parents she hears a preacher telling the congregation that “whom the Lord loveth he chasteneth,” Phosy wants the Lord to love her and therefore prays that he will chasten her, for this will prove His love. She is too young and too innocent to realize that her life is already a kind of chastening, though one she does not deserve. Phosy becomes obsessed as Christmas draws near with the idea that on that day Jesus will be born — Jesus is somehow born anew each year on Christmas day, she thinks, and she hopes that when he comes again this year he will bring her the gift she so earnestly desires.

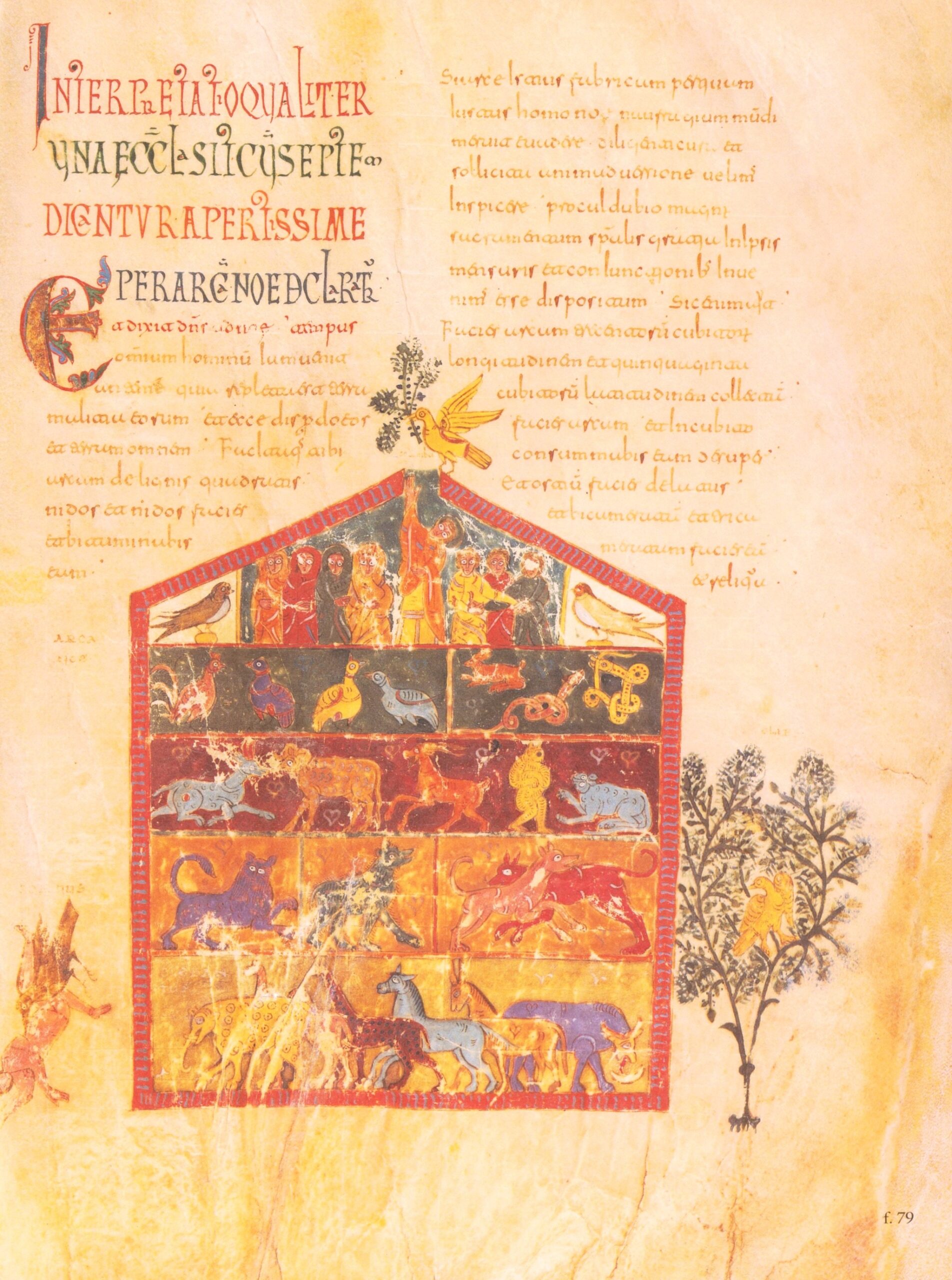

So she’s anxious as the day draws near, and her parents are also anxious, but for a different reason: her stepmother’s pregnancy is coming to term. On Christmas morning the stepmother gives birth to Phosy’s little brother, and in all of the stress and anxiety — and, as it turns out, tragedy — of the event, Phosy is completely forgotten. So she dresses herself and comes downstairs and wanders into a spare room of the house … and she sees lying there, alone and still, a beautiful baby boy. It is, she knows, the baby Jesus, come to give her the gift of Himself, and, she devoutly hopes, his chastening also. So she takes the little boy in her arms: he’s perfectly beautiful, but he is also, she realizes, very cold. And so she holds him close to herself to give him her warmth — and it is in this position that her father finds her. And for the first time Phosy weeps. She weeps because there was no one to care for the baby Jesus when he came, and so he died.

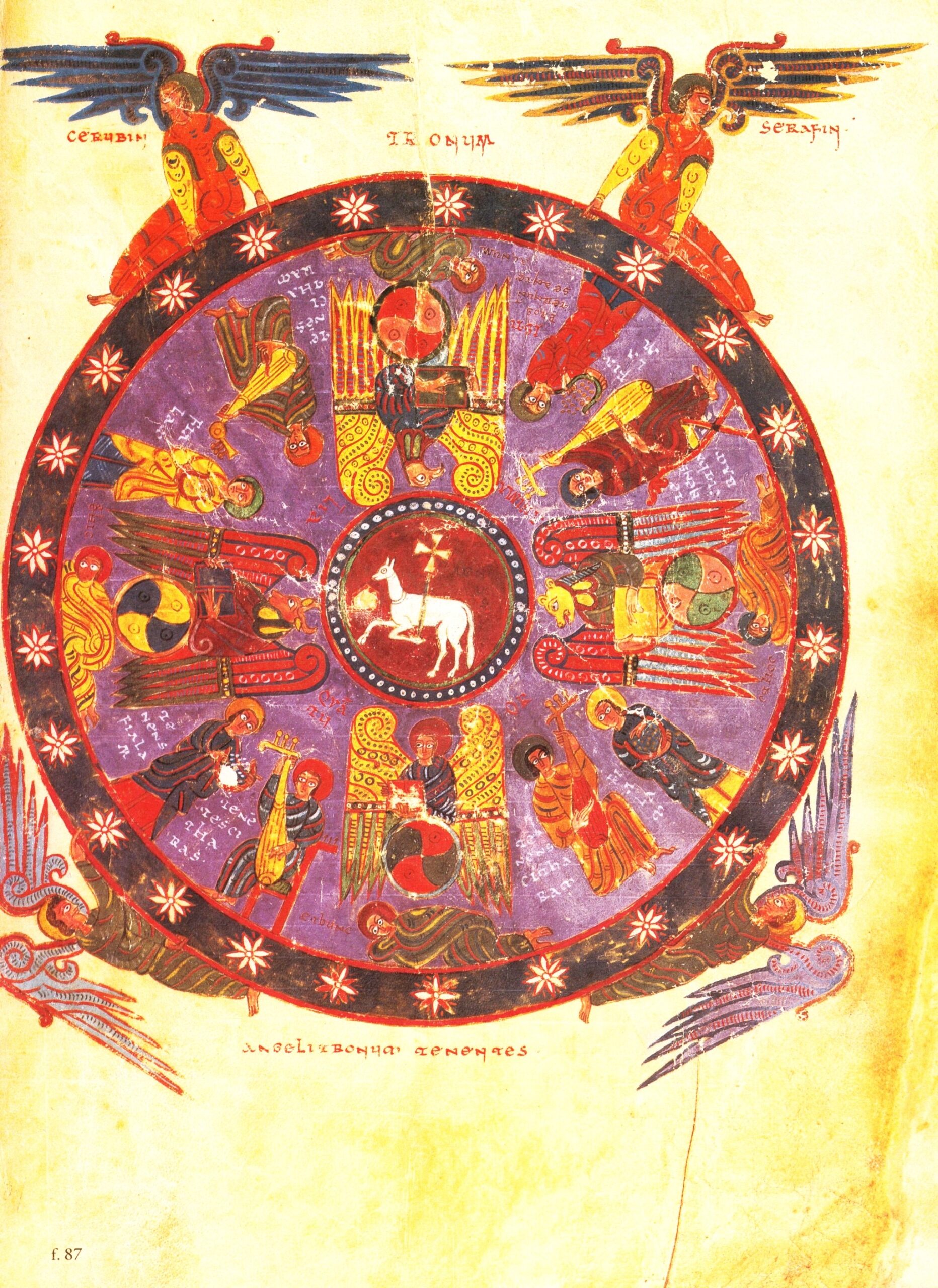

It is an extraordinary image that George MacDonald has conjured here, for this is of course a Pieta. It is Mary bearing the body of her dead son, conveyed to us through a small English girl bearing the body of her dead baby brother. Here superimposed on Christmas Day, that most innocently festive of days, is the immense tragedy of Good Friday.

But we do call it Good Friday, do we not?

When Phosy’s father sees her holding her infant brother he sees something in Phosy that he has never noticed before: he discerns the depth and the intensity of her compassion. And he has already been altered in his attitude toward his wife by seeing her grief at the loss of her child. Throughout this story he has only thought of the women in his life as either meeting or failing to meet — though in fact always failing to meet — his expectations; but when he sees his wife and daughter so wounded, their tenderness of heart draws out his own, and a great work of healing begins in this damaged family, a family damaged above all by the absence of paternal love.

“Such were the gifts the Christ-child brought to one household that Christmas,” says MacDonald. “And the days of the mourning of that household were ended.” A knitting up of their raveled fabric begins, and the extraordinary thing is that the chief instrument of that mending is death: the death of Jesus as a man on a cross, or the death of Jesus as an infant in Victorian London, it is one Sacrifice. This is what Charles Williams pointed to when he wrote that the Christian way is “dying each other’s life, living each other’s death.”

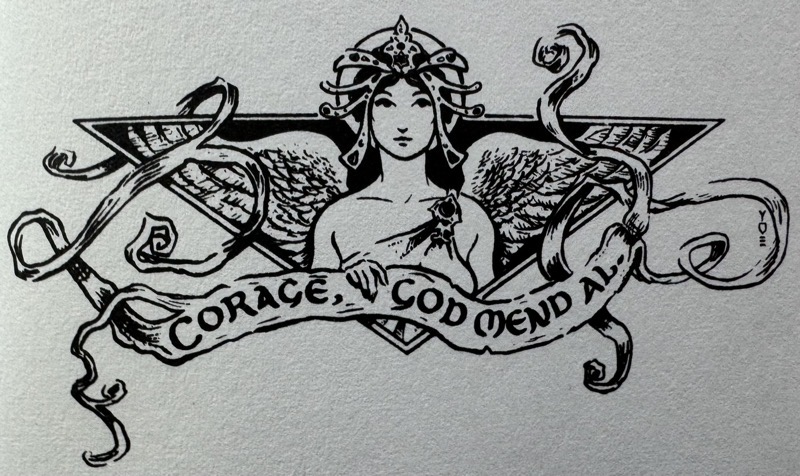

In his beautiful book Unapologetic Francis Spufford has Jesus say, “Far more can be mended than you know.” And this is what “The Gifts of the Child Christ” tells us also. George MacDonald made for himself a personal motto — an anagram of his name, imperfectly spelled because in this world things that are mended still show the signs of their frayed or broken state. Mended but not yet perfected are the things and the people of this world, at their very best. MacDonald’s motto was:

The richest of Christmas blessings to you all.

The game Monopoly basically copied an anti-capitalist game created by one Lizzie Magie: The Landlord’s Game.

Finished reading: The Corner that Held Them by Sylvia Townsend Warner. A strangely riveting book, and unlike anything I have ever read. I don’t even know how to describe it. 📚

My first thought when I read the-fediverse-is-the-future pieces is: Great, now whenever anyone anywhere online is posturing, preening, snarking, lying, manipulating, and trying to stir up hatred of their enemies, we all can see it!

The fediverse would be a great thing if so many of the people using the various social media platforms weren’t simply seeking to continue all the bad behavior that made Twitter “the hellsite.” I don’t think enough people have learned from that experience. My fear is that the fediverse will just end up being the helliverse, so I’m thankful that micro.blog makes federation opt-in.

Brian Eno, from a 1995 diary entry:

Whatever you now find weird, ugly, uncomfortable and nasty about a new medium will surely become its signature. CD distortion, the jitteriness of digital video, the crap sound of 8-bit – all these will be cherished and emulated as soon as they can be avoided.

It’s the sound of failure: so much of modern art is the sound of things going out of control, of a medium pushing to its limits and breaking apart. The distorted guitar is the sound of something too loud for the medium supposed to carry it. The blues singer with the cracked voice is the sound of an emotional cry too powerful for the throat that releases it. The excitement of grainy film, of bleached-out black and white, is the excitement of witnessing events too momentous for the medium assigned to record them.

Wish I had seen this before I wrote my “Resistance in the Arts” essay. But I think if I had read a lot more Eno I probably wouldn’t have felt the need to write the essay at all.

The Feast of the Annunciation is on March 25, but the lectionary gives us the story also on the fourth Sunday of Advent, so this is a good time to read Andrew Hudgins’s great poem “The Cestello Annunciation.”

Last night at St. Alban’s, we had an utterly wonderful service of Nine Lessons and Carols. The history of the service — it’s relatively new as these things go — is fascinating.

Charlie Warzel: “A shift away from a knowable internet might feel like a return to something smaller and purer. An internet with no discernable monoculture may feel, especially to those who’ve been continuously plugged into trending topics and viral culture, like a relief. But this new era of the internet is also one that entrenches tech giants and any forthcoming emergent platforms as the sole gatekeepers when it comes to tracking the way that information travels. We already know them to be unreliable narrators and poor stewards, but on a fragmented internet, where recommendation algorithms beat out the older follower model, we rely on these corporations to give us a sense of scale. This might sound overdramatic, but without an innate sense of what other people are doing, we might be losing a way to measure and evaluate ourselves. We’re left shadowboxing one another and arguing in the dark about problems, the size of which we can’t identify.”

I wrote about library catalogs, analog and digital.

Expectation.

Pope Francis Allows Priests to Bless Same-Sex Couples - The New York Times:

But the new rule made clear that a blessing of a same-sex couple was not the same as a marriage sacrament, a formal ceremonial rite. It also stressed that it was not blessing the relationship, and that, to avoid confusion, blessings should not be imparted during or connected to the ceremony of a civil or same-sex union, or when there are “any clothing, gestures or words that are proper to a wedding.”

What does it mean to bless a couple without blessing that couple’s relationship? Millions of words will be expended in the coming months to try to explain this, but I can guarantee that none of them will make sense. The Pope has put his church in a completely untenable, incoherent, radically unstable position. From here it will have to go back to the traditional teaching or ahead to something wholly unprecedented. And I can’t imagine a retreat, not by this Pope.

Francis has not spoken ex cathedra here — this is not like, for instance, Munificentissimus Deus. But it’s a big thing, and if the incoherence is rectified by further acceptance of same-sex unions, then some really fancy theological dancing will have to be performed to avoid having to admit that the historic dogma on sex and marriage was simply wrong. And if a future Pope walks this back, then a similarly complicated dance will have to be done to reconcile the repudiation of Francis’s teaching with the dogma that the Pope is guided and directed by the Holy Spirit even when making ordinary — not ex cathedra — arguments and policies. It’s hard to see how historic Catholic teaching on marriage and historic Catholic teaching on papal authority can emerge unscathed from this.

Is Francis now the most consequential pope in the history of Roman Catholicism? I am inclined to say Yes.