a revaluation

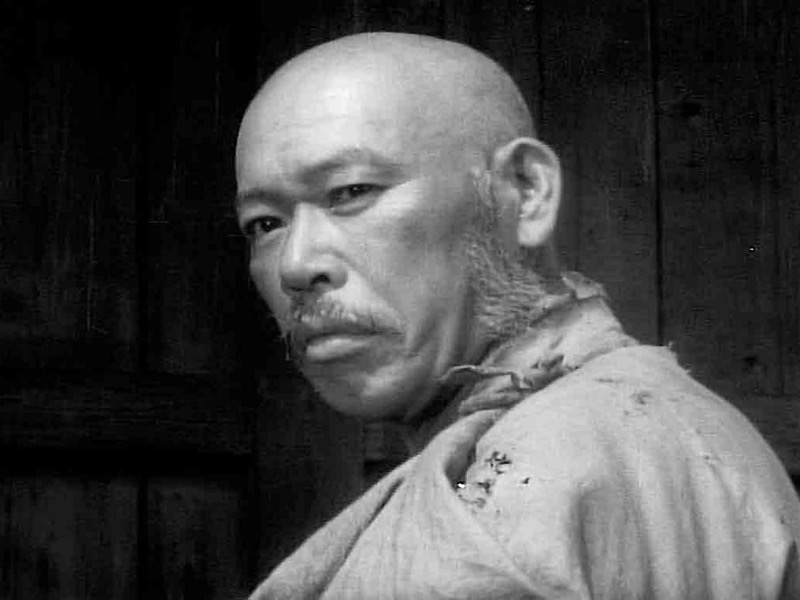

Here is the great Takashi Shimura as Kambei Shimada, the leader of The Seven Samurai (1954):

A man to be reckoned with. A calm but unyielding and fearless leader of warriors. And here’s Shimura two years earlier, as the dying bureaucrat Mr. Watanabe in Ikiru — a timid man, a man so lifeless and dull that one of his co-workers nicknames him “the Mummy”:

He was also the kindly peasant woodcutter in Rashomon and the professor in the original Godzilla! Which is a pretty remarkable string of major roles, comparable perhaps to Harrison Ford’s run in the early 80s as Indiana Jones, Han Solo, and Rick Deckard. But Shimura’s sheer range is unmatched, I think. Even now, forty years after his death, we ought to be talking about what an astonishingly versatile actor Shimura was, compelling in every role.

But that’s just by-the-way. What I really want to talk about here is the filmmaker most closely associated with Shimura, the director of Rashomon and The Seven Samurai and Ikiru, Akira Kurosawa. (No, Kurosawa didn’t direct Godzilla, but if he had….) The argument I want to make here is that Kurosawa has experienced a fate that no one would have predicted of him fifty years ago: as a director, he is significantly underrated.

For many years, starting with the overwhelmingly delighted response to Rashomon at the Venice Film Festival in 1951, Kurosawa was the Japanese film director — he eclipsed all others, at least in the eyes of Western audiences. (Indeed, you could make the case that The Seven Samurai is the most influential film ever made — even if you think only of how many movies have stolen its most obvious plot device, the let’s-assemble-the-gang first act. But the way Kurosawa films his action scenes, copied by filmmakers ever since, has been equally influential.) But this celebration of Kurosawa did nothing to elevate the status of other Japanese filmmakers, including the two who have a strong claim to be his superiors: Yasujiro Ozu and Kenji Mizoguchi. They only gradually made their way into the public consciousness.

One of the best film critics alive — one of the best ever —, David Thomson, has written that he has often been rather hard on Kurosawa precisely because he is annoyed that Kurosawa’s reputation has displaced Ozu and Mizoguchi, whom he thinks obviously the greater artists. But that was a mistake, for two reasons: first, because you cannot elevate the reputation of some by attacking the reputation of others — it just doesn’t work that way; and second, because it is not at all obvious (to me, anyway) that Kurosawa is a lesser filmmaker than Ozu and Mizoguchi.

I don’t say this carelessly. If I had to pick a Greatest Director, it would probably be either Ozu or Jean Renoir. But lately I have been thinking about this: Kurosawa is best known for his historical films, especially the ones focused on samurai culture, and yet Ikiru — a film set in 1950s Japan, in an urban setting, focusing on family and the workplace — in short, a film very like Ozu’s most famous ones, a perfect example of the shomin-geki — may well be Kurosawa’s masterpiece. And it is in every way worthy to be compared with Ozu’s transcendentally great Tokyo Story and Late Spring.

That still could easily have been from Ikiru, though in fact it’s from Late Spring. The two films occupy much the same world.

To be sure, anyone who knows Ozu’s cinematic grammar would never for a moment think that Ikiru was one of his films. The camera is too mobile; the height of the shots too variable; the transitions too different. (Kurosawa frequently employs horizontal wipes to change scenes, something Ozu probably never did in any of his forty or more films.) Still, Ikiru and Ozu’s masterpieces of the same era are spiritually kin — closely kin; they tug at my heartstrings in very similar ways, with very similar effects. And if Kurosawa could make an Ozu-like film, Ozu could never in a million years have made The Seven Samurai.

So I’m on something of a Kurosawa kick right now, and re-evaluating his body of work. He’s much less subtle than Ozu and Mizoguchi … but subtlety isn’t everything. Sometimes the direct approach is the best. And rarely did any director make the direct approach more skillfully and compellingly than Kurosawa does.

Really excited for this work-in-progress by Samuel Arbesman called The Magic of Code.

Currently reading: Raymond Chandler: the Library of America Edition by Raymond Chandler 📚

Finished reading: Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell by Susanna Clarke. A masterpiece. 📚

New evidence of Rosalind Franklin’s role: “as an equal member of a quartet who solved the double helix, one half of the team that articulated the scientific question, took important early steps towards a solution, provided crucial data and verified the result.”

Oklahoma and Muswell Hill

Here I’ve joined together two posts that I wrote a decade or so ago at The American Conservative (which has memory-holed most if not all I wrote for it). The first one:

Ray Davies, the leader and songwriter of the Kinks, grew up in a large and eccentric working-class family in north London. He was the seventh of eight children, a somewhat shy and easily frightened child whose chief comforter was his sister Rene, who was eighteen years older than him. During the Second World War, when Ray was just an infant, Rene had fallen in love with a Canadian soldier posted in London, married him, and moved to Canada.

But their marriage was unhappy. Rene’s husband drank heavily and sometimes beat her; they argued constantly, and to escape him she would frequently return to the family home in Muswell Hill for extended stays, at first alone, later with her son. Like all of the Davieses she was musical, and enjoyed playing show tunes on the piano; the family tended to sing and play its way through hard times, of which they had plenty.

Rene was making one of her visits home when her kid brother turned thirteen, which she believed to be a special birthday deserving of a special present: she bought him a Spanish guitar he had been coveting for some time. She sat at the piano and they played a song together.

That evening, Rene decided to go dancing with friends at the Lyceum Ballroom in the West End. This was not, in the opinion of her doctor or her mother, a good idea: Rene had had rheumatic fever as a child, and it had weakened her heart. But, as Ray would write later in his autobiography, she had always loved to dance, and her life was hard and her violent husband very far away; she was not inclined to deny herself a cherished pleasure. On the dance floor of the Lyceum that evening she collapsed and died, as the big band played a tune from Oklahoma!

Only a quarter-century later did Ray Davies write the lively song that celebrated his sister Rene’s love of dancing: a song that gave her a longer, and happier, life than had been her actual lot. Ever since I learned what lies behind this little song, it has touched me.

Come dancing, Come on sister, have yourself a ball, Dont be afraid to come dancing, Its only natural.Come dancing, Just like the Palais on a Saturday, And all her friends will come dancing Where the big bands used to play.

And here’s the second post:

In the comments to my previous post on Ray Davies of The Kinks, one reader linked to a YouTube version of a lovely ballad called “Oklahoma U.S.A.” The kind person who made that video (which I’ve not linked to here) seems to be under the impression that the song is about Oklahoma, but it’s not: it’s about the romance of America for working-class Brits half-a-century ago, as they saw America on the movie screen.

And yet the Muswell Hillbillies loved their place in the world. Rene repeatedly escaped from her unhappy marriage by returning to a home which, however shabby it may have been, gave her love and stability. It seems that for her there was something particularly consoling about hearing those American show tunes at the Lyceum Ballroom not far away, and playing them on the beaten-up old piano in her parents’ front parlor. And Ray Davies’s nostalgia for the world of his childhood is palpable throughout his music and well as in his autobiography.

I’m reminded here of several books by the remarkable English writer Richard Hoggart in which he celebrates his own urban working-class upbringing, in Leeds rather than London, and laments its displacement by an electrically-disseminated mass culture. But as he describes the place of singing in his upbringing — his community was intensely musical in much the same way that Davies’s family was — something odd emerges: these people weren’t singing English folk songs, but rather hit tunes they had heard on the wireless. He describes, for instance, the huge influence of Bing Crosby’s “crooning” style on the amateur singers in the local “workingmen’s clubs.”

There seems to have been a period, then, in England and I think in America too, when electrical technologies (primarily radio and movies) connected people with a larger world that shaped their dreams and aspirations — but without wholly disconnecting them from their local culture. Instead, it seems, they managed to incorporate those new and foreign songs into their local culture. Oklahoma! might show you some of the shortcomings of your world, but it didn’t necessarily make you hate it. There was a way to bring those distant beauties into your everyday life.

But perhaps this can only be done if you’re a creator and performer as well as a consumer. Davies’s sister Rene went to the movies, yes, but she also danced in the ballrooms and played piano with her brother. She made those songs her own by using her body and her voice, rather than merely observing the words and movements of others. Perhaps we have the power to incorporate mass culture into our lives — but not by just consuming it.

Last night when proofreading my newsletter, I saw that I had misnamed the founder of the Paragon Ragtime Orchestra. (Instead of Benjamin, I wrote Franklin – obvious how that brain fart happened.) I was so pleased to have corrected myself in time … but I forgot to hit Save. Grrrrrrr.

Is our society’s Overton window unresizeable?

This week I did a one-topic newsletter, on Scott Joplin. I rarely do these – they don’t feel like a great fit for the medium – but I’d like to do more.

an unresizeable window

Does any society ever grow more tolerant? That is: Does acceptance of a position or a group hitherto untolerated ever come without the rejection of another position or group previously tolerated?

My suspicion is that the Overton window of any given place and time can’t be resized, it can only be moved. That is, there’s a politico-ethical equivalent of Dunbar’s number, a relatively fixed range of positions that at any one time can be accepted as potentially valid, or at least not-to-be-extirpated. Greater inclusion, if my suspicion is correct, never happens: an extension of toleration in one direction requires a constriction of toleration in the other, in order to avoid social chaos.

I’m sure I’m not the first to say this. But I think it’s important.

Finished reading: Looking for the Good War by Elizabeth D. Samet. This one was disappointing: too predictable and pedestrian. 📚

Currently reading/listening: Glenn Gould - The Goldberg Variations - The Complete Unreleased Recording Sessions June 1955. An extraordinary experience. 📚 ♫

Currently reading: Looking for the Good War by Elizabeth D. Samet 📚

Another Sherman Alexie comment: “Self-censorship among writers is a real and serious problem in this era. To believe otherwise either means you live and work in a very small circle of like-minded friends or that you think this self-censorship is a good thing.” Surely people who organize social-media campaigns against wrongthink do indeed believe that self-censorship is a good thing. The point of such campaigns is less to punish already-published writing than to intimidate writers going forward. If writers self-censor for fear of offending someone, that’s precisely the goal of the intimidators.

Sherman Alexie’s comment that “the right wing are censorship vikings and the left wing are censorship ninjas” is accurate and useful.

Finished reading: Reinventing Bach by Paul Elie. What an extraordinary book — so glad I decided to revisit it a decade after I first read it. My head is just buzzing with ideas. 📚

I get why you need to chew it, but why do I have to hold it?

Getting closer….