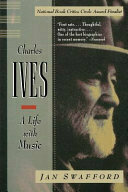

Finished reading: Charles Ives by Jan Swafford. A superb biography of one of the most peculiar composers: an ordinary man in almost every respect who simply heard, and couldn’t stop hearing, music that no one else could make sense of. 📚

Gregory Nazianzus: “Yesterday I was crucified with Christ, today I am glorified with him; yesterday I died with him, today I am made alive with him; yesterday I was buried with him, today I rise with him. But let us make an offering to the one who died and rose again for us. Perhaps you think I am speaking of gold or silver or tapestries or transparent precious stones, earthly matter that is in flux and remains below, of which the greater part always belongs to evil people and slaves of things below and of the ruler of this world (John 14:30). Let us offer our own selves, the possession most precious to God and closest to him. Let us give back to the Image that which is according to the image, recognizing our value, honoring the Archetype, knowing the power of the mystery and for whom Christ died.”

Currently watching/listening: Netherlands Bach Society, Easter Oratorio ♫

Our little boy is growing up.

- I follow several Twitter accounts via Feedbin, & often click through to twitter.com.

- Twitter cuts off Feedbin’s access to force people like me to view tweets only on twitter.com.

- I stop reading those Twitter accounts and now never visit twitter.com.

Currently listening: Bach, St. Matthew Passion ♫

I wrote about Le Guin and Tolkien in what is also a Good Friday meditation.

beyond daylight ethics

In a 1975 essay called “The Child and the Shadow,” Ursula K. Le Guin wrote:

In many fantasy tales of the 19th and 20th centuries the tension between good and evil, light and dark, is drawn absolutely clearly, as a battle, the good guys on one side and the bad guys on the other, cops and robbers, Christians and heathens, heroes and villains. In such fantasies I believe the author has tried to force reason to lead him where reason cannot go, and has abandoned the faithful and frightening guide he should have followed, the shadow. These are false fantasies, rationalized fantasies. They are not the real thing. Let me, by way of exhibiting the real thing, which is always much more interesting than the fake one, discuss The Lord of the Rings for a minute.It’s a sweet little pivot that Le Guin executes in that paragraph’s last sentence, because many of her readers would have assumed that her critique included Tolkien – but no. She admits that “his good people tend to be entirely good, though with endearing frailties, while his Orcs and other villains are altogether nasty. But,” she continues, “all this is a judgment by daylight ethics, by conventional standards of virtue and vice. When you look at the story as a psychic journey, you see something quite different, and very strange.” Daylight ethics is insufficient to account for the greatness of The Lord of the Rings: it may in certain respects be “a simple story,” but “it is not simplistic. It is the kind of story that can be told only by one who has turned and faced his shadow and looked into the dark.” And:

That it is told in the language of fantasy is not an accident, or because Tolkien was an escapist, or because he was writing for children. It is a fantasy because fantasy is the natural, the appropriate, language for the recounting of the spiritual journey and the struggle of good and evil in the soul.Which is why when she herself had a story like that to tell, she turned to fantasy.

In most respects, Earthsea is a radically different world than Tolkien’s Middle-Earth, but that perhaps makes the correspondences all the more worth noting. As I was rereading The Farthest Shore recently it struck me how faithfully the journey of Ged and Arren to the Dry Land echoes the journey of Frodo and Sam to Mordor – down to the point that Ged’s helper Arren has to carry him for a brief period, in much the same way that Frodo is carried by Sam (though in Le Guin’s tale after the decisive moment rather than before).

That said, Le Guin has created a world in which the protagonist has a different kind of helper than Frodo does. The relationship between Frodo and Sam is that of master and servant – as Sam’s deferential language continually reminds us – but the young man who accompanies Ged to the Dry Land is not a servant at all. He is a prince, soon to be a king, and had been shocked to learn just after meeting Ged that this Archmage, this titan among wizards, had been in his childhood a goatherd on a distant dirty island. But he is much younger and less experienced than Ged, and Ged is, after all, a mage, which Arren is not. So matters of status are very much in question here. Ged takes upon himself the burden of teaching Arren, assumes an authority over him in certain respects, an authority that Arren sometimes accepts and sometimes resents. Their relationship is much more complex than that of Frodo and Sam; it is constantly in negotiation.

What is Le Guin doing with this acknowledgement of and then swerving from the Tolkienian model? Well, I think this is very closely related to her fascination with Daoism, and illuminates certain contrasts between Confucianism and Taoism – especially as regards the purpose of education. Among other things, Confucianism is a way of breeding rulers. It emphasizes righteousness (yi 義) as a key virtue – but especially for rulers. (See this overview by Mark Csikszentmihalyi.) The practice of yi is essential to legitimizing and consolidating political authority – and this is why the famous Imperial Examination, used to identify candidates for civil service, was so deeply grounded in the neo-Confucian classics.

By contrast, Daoism does not make governors but rather sages, and the Daoist sage has no interest in ruling. If the key virtue of the Confucian ruler is righteousness, the key virtue of the Daoist sage is inaction: wuwei. And this is the virtue that Ged, knowing who Arren will become, tries to teach him. That is, Ged believes that even for a king righteousness sometimes may be inadequate. He says to Arren,

“It is much easier for men to act than to refrain from acting. We will continue to do good and to do evil. … But if there were a king over us all again and he sought counsel of a mage, as in the days of old, and I were that mage, I would say to him: My lord, do nothing because it is righteous or praiseworthy or noble to do so; do nothing because it seems good to do so; do only that which you must do and which you cannot do in any other way.”Ged is preparing Arren not for kingship as it is typically understood – the “daylight ethics” of Confucianism would be adequate for that – but rather the the possibility of a “psychic journey,” a spiritual challenge.

When in the Dry Land they meet the undead mage who goes by the name of Cob, they are encountering one whose path to power, and to great evil, had years earlier been opened for him by Ged. That opening was quite inadvertent, to be sure: Ged wished to act righteously in disciplining Cob, who had dabbled in necromancy, but his actions – driven in part, he admits, by his pride, his desire to demonstrate his greater power – had precisely the opposite effect than he had intended. Cob became more, not less, obsessed with necromancy and the conquest of death. (He is in some ways the proto-Voldemort, a would-be Death Eater.) Ged acted thus because he thought it “righteous or praiseworthy or noble to do so”; but it was not what he had to do, and it could have been done in some other way, some less humiliating and degrading way. The problem with action, as Daoism teaches and as Ged tries to teach Arren, is that it always, always, has unexpected consequences, often profoundly unwelcome ones.

To their final confrontation with Cob Arren brings an instrument appropriate to a ruler and a warrior: a sword. Again and again he strikes Cob, severing his spinal cord, splitting his skull … but Cob simply reassembles himself. “There is no good in killing a dead man.” Ged, by contrast, brings but “one word” that stills Arren and Cob alike. (We do not hear the one word is, but Ged says that it is “the word that will not be spoken until time’s end.”)

And then what Ged must do – must do, and cannot do in any other way – is to pour out all his own magical power, leaving nothing inside, not to inflict a wound but to close one; not to sever but to knit together. Cob had made a gap in the cosmos through which Death entered the world of the living; and that could be healed not by a Confucian king but by a Daoist sage.

But something a little, or a lot, more than a Daoist sage: here, I think, the guiding shape of Tolkien’s story takes Le Guin a step beyond what Daoism can envisage. Like Frodo, Ged undertakes a kenosis, a self-emptying; except that what Frodo cannot do without the intervention of his Shadow, Ged completes. “It is done,” he says. It is finished. And when Arren takes up his crown, he knows that he owes it to Ged; the same knowledge leads Aragorn to kneel before Frodo.

Near the novel’s end, the Doorkeeper of Roke says of Ged, “He is done with doing. He goes home.” And still later Ged will wonder why he outlived his magic. Which raises the question: What happens after “it is finished”? There, I think, our three stories diverge.

P.S. re: where a story can take a writer

Le Guin, from her Afterword to The Farthest Shore: “It would be lovely if writing a story was like getting into a little boat that drifted off and took me to the promised land, or climbing on a dragon’s back and flying off to Selidor. But it’s only as a reader that I can do that. As a writer, to take full responsibility without claiming total control requires a lot of work, a lot of groping and testing, flexibility, caution, watchfulness. I have no chart to follow, so I have to be constantly alert. The boat needs steering. There have to be long conversations with the dragon I ride. But however watchful and aware I am, I know I can never be fully aware of the currents that carry the boat, of where the winds beneath the dragon’s wings are blowing.”Took me about two days of using a Mac with a Touch Bar to realize that I would go insane if I didn’t install Bar None.

Tim Larsen on Philip Jenkins’s new book on Psalm 91: “Sometimes called ‘the Protection Psalm’ because of its blanket assurances, it seems the very definition of over-promising: ‘A thousand shall fall at thy side, and ten thousand at thy right hand; but it shall not come nigh thee’. … Many religious leaders have therefore found Psalm 91 a bit of an embarrassment. They have been at pains to point out that it reflects a naive, primitive kind of belief; as such, it is best for moderns to not take its words too much to heart. Yet the faithful can demonstrate a devotion to the psalm that is hard for the sophisticated to grasp.”

Robin Sloan: “I have wanted to greeble something for a very, very long time. Maybe for my entire conscious life. I regret that it took me this many years to get here, because it was exactly as much fun as I imagined.”

Anne Trubek: “I no longer feel a need to prove anything through my choice of book to read. I often barely even remember them a day or two later, and that’s just fine. I am again like I was when young, sitting on that floor looking up at shelves of spines, deciding what to read based entirely on back cover copy and whim. Short or long, old or new, funny or devastating. It’s a gift and a solace: pleasure severed from ambition or duty.” I wrote a whole book about this!

Listening to All Melody - Nils Frahm ♫

One common problem with the computational photography of smartphones: it gets overwhelmed by bright colors. (If you’re in point-and-shoot mode – you can make adjustments if you know what you’re doing.) My pseudo-Leica handles those colors beautifully.

Heterodox Academy: “If scientific institutions continue to openly and preferentially support the progressive wing of the Democratic party’s preferred positions and causes, then we shouldn’t be surprised if public support for the scientific community eventually approximates its support for the progressive wing of the Democratic party.”