low anthropology

In my new essay on anarchism, I describe myself as “a person with an exceptionally low anthropology” — and if you want to know what I mean by that, here’s more from David Zahl.

Nothing like listening to the Welsh sing their anthem. 🏴

I’ve been predicting U.S. 0-0 Wales, but the power of Weston McKennie’s hair is (against my will) raising my hopes.

After seeing that shambolic defending by Iran, I might have to reconsider my prediction that the U.S. will finish behind them…. ⚽️

The Church universal also has a set of overlapping responsibilities, but how these responsibilities are translated into the work of individual churches is a tension of its own. Local churches are first obligated to their own members, to preach, worship, disciple, and administer the sacraments. Adding anything beyond this to any individual church is tying on a burden too great to bear. Yet the Body of Christ spread across the world is also responsible for sending messengers of the Gospel to places that have not yet heard it, meeting the needs of the poor (local and distant), and advocating for justice in whatever society they find themselves in. (I would draw primarily from Isaiah 58 as the source of the lattermost impetus.) The Body of Christ also has an obligation to be in communication with itself such that the hand can know if the eye is suffering and then do something about it.

This task might seem impossible, but the power of the Holy Spirit among God’s people allows us to order ourselves according to the moral obligations we have to one another and to the world. We seek in prayer to know which people in need we ought to be in proximity to, and we obey accordingly as we embark on whichever road to Jericho we are called to. Some may physically remain wherever they are; others may move across town, across the country, or across the world. The wealth of believers, once yielded to the direction of the Holy Spirit, also has centripetal and centrifugal forces acting upon it but should in general go to where there is the greatest need and the least knowledge of the Gospel.

A long, complex essay, incisive and provocative. Every thoughtful Christian should read it. I hope to comment more fully later.

It feels like a theme park. There’s always been this ridiculous corporate circus, but generally it intersects with a real sense of joy, and you monetise the joy. Here, there’s no joy, just monetising. You feel that this is a place that should in no world be staging this, until you realise: the World Cup is not a festival of football, it’s a travelling city state, a TV show sold to people who can pay the most money. You want a World Cup? This is what a World Cup is.

subsidiarity

While the Distributist movement gained a much larger following than most historians have acknowledged, and is even experiencing something of a revival these days, it has suffered from being dismissed. Conservatives (and capitalists) accuse Distributism of being too socialist, an enemy of free trade. Liberals (and socialists) accuse it of being too capitalist, an enemy of regulation and the public interest. But more often it is dismissed without a fair hearing – not only by established economists and academics but by most everyone else as well – simply because of its unfortunate name: Distributism. No one knows what it means, and usually people think it means something else. It is understandably conflated with redistribution, which means taking money from a wealthier segment of the citizenry and redistributing it to a less wealthy segment. Sort of like Robin Hood. Or taxation. Yet while the early Distributists recognized that some redistribution of land, wealth, and power would obviously be necessary to achieve their ends, redistribution was never their end goal nor what made their vision compelling to so many.

It is for this reason that the Society of Gilbert Keith Chesterton recently renamed Distributism. Now, I wish to make it clear that we don’t have any special control over the word “Distributism.” People can keep using the old word if they want. But we introduced a new word because the old word was … well, it was no good!

The new word we came up with is “Localism.”

I see why they did this, but (a) “localism” is already a term used in other contexts and (b) at least “Distributism” captured the fact that the movement is not just cultural but also a project of political economy.

Distributism/Localism, like anarcho-syndicalism and several other kinds of anarchism — which I am very much interested in — all think that our social and cultural problems cannot be fixed unless we can wrest economic control from Bosses and put it in the hands of local people. They are all subsidiarist movements, and these are all to some degree rooted in Catholic social teaching, so you would think that people who call themselves conservatives would at least be interested. Not so much, not any more.

Currently reading: Trading Twelves: The Selected Letters of Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray 📚

Charles Spurgeon: “I do not know that the prodigal saw his father, but his father saw him. The eyes of mercy are quicker than the eyes of repentance. Even the eye of our faith is dim compared with the eye of God’s love. He sees a sinner long before a sinner sees him.”

Just as you were starting Tolstoy Together, you wrote in The New York Review’s pandemic journal: “Twice during the most difficult periods of my life, I could do little but read [War and Peace]. There were days when I would hand-copy passages from it just to keep my brain and hands in movement.” What did you appreciate about the experience?

My understanding, from my own experience, is that agitation does much harm to our minds. It is a most time-conscious state — every minute is devastatingly long when one’s perception of time becomes disoriented. I hand-copied passages from War and Peace during two difficult times of my life, several years apart: when I was suicidally depressed, and after I lost a child to suicide. The activity was a defiance against that harmful timelessness: here time does pass from one line to the next.

Lately, I’ve been hand-copying Moby-Dick first thing in the morning, before coffee, to carve out a space for my brain and my hands, to have a definite frame of time. I suppose I do that as others practice yoga or meditation.

When I first conceived of this essay, I imagined it would be purely literary. Then, the presidential election arrived with all of its turmoil. I suddenly cared very little about aesthetics and the nuances of figurative language. I was at a loss until I remembered that much of Baldwin’s writing came to exist during moments of American crisis: the civil rights movement and its aftermath, the decimation of the Black Power movement, the rise of Reaganomics, the devastating AIDS epidemic. Baldwin was forged in the crucible of an America perpetually teetering on the edge of self-destruction, unwilling to heed the warnings of those who understood the immensity of the peril. The result of that heedlessness, as we’ve seen in these pandemic months, is quite literally death. It occurred to me, then, that John’s experience, and Baldwin’s novel as a whole, is an act of bearing witness to the bitter realities of his life as a young man — and to the Black church as a place of existential and spiritual nourishment, even as it was parochial and unyielding.

Perhaps Baldwin left the church because he knew he would not have survived its stifling rigors, and had little desire to try. Certainly the exacting and capricious God of his upbringing — these characteristics that, not coincidentally, also describe Gabriel Grimes — was anathema to him. And yet in his 1962 essay “Down at the Cross: Letter From a Region in My Mind,” Baldwin wrote of his vexing childhood religion: “In spite of everything, there was in the life I fled a zest and a joy and a capacity for facing and surviving disaster that are very moving and very rare.”

As an endlessly corrupt World Cup begins, the American college-sports-industrial complex says, “Hold my beer.”

Mastodonic thoughts

After a brief period on Mastodon: It’s exactly like Twitter. People have taken all their Twitter habits — lecturing, hectoring, making demands, sneering, mocking, belittling, preening, self-congratulating — and transferred them unchanged to a new platform. No one, it appears, learned anything from what even they called the “hellsite.”

Me miserable! which way shall I fly Infinite wrath and infinite despair? Which way I fly is Hellsite; myself am Hellsite; And, in the lowest deep, a lower deep Still threatening to devour me opens wide, To which the Hellsite I suffer seems a Heaven. O, then, at last relent! Is there no place Left for wisdom, none for kindness left? None left but by deletion….Account deleted.

UPDATE 2022-11-22: It occurs to me that when Mastodon decided to implement its version of the retweet (they call it the “boost”) its fate as Undead Twitter was sealed. If you could blame only one thing for the ruination of Twitter, it should be the RT. The RT is a frictionless way to spread whatever arouses users emotionally, and what arouses users emotionally is almost always something deceitful and/or malicious. The RT is the death of charity, the death of peace, the death of truth. And therefore for me the death of Mastodon.

Corner Club Cathedral Cocoon, by Sasha Frere-Jones:

I developed a new way of thinking about how we listen to music, together or alone. My alliterative schema for the various listening environments, designed to be annoyingly mnemonic, is corner, club, cathedral, and cocoon. The corner (as in street corner) is where people take priority over sound, and this model encompasses both a block party using a multi-speaker sound system on the street and the digital commons of web radio stations and streaming platforms like Mixcloud and SoundCloud. One of my favorite web radio stations, LYL Radio, was established by Lucas Bouissou, who stated his view firmly: “About audio quality, honestly, I don’t give a shit.” LYL Radio is very much the corner, in every sense.

The cathedral is an environment built by the audiophile, where reflection is the norm. You don’t have to be alone, but if there are a bunch of listeners together, you’re not talking to one another. You listen, and only listen. One arrives here with a certain amount of time and money, introducing an exclusive element, which I don’t love, but if I imagine a house of worship with its doors flung wide open, I am less uneasy, because the resources are oriented toward establishing a common good.

The club is halfway between these two points, presenting a certain level of audio quality, but not at the expense of interaction. If there is an emphasis in the club, it is about people connecting through music. The cocoon, meanwhile, is where most people find music now, through earbuds and headphones, locked into the cycle of wage labor or exercise.

Emphases mine. I like this taxonomy. I am very much a cathedral guy, though without either the budget or the inclination to be an audiophile. (As Free-Jones says later in his excellent essay, “An obsession with the quality of recordings is, on some level, antithetical to the spirit of mindful listening.“) Let’s say that my preferred environment isn’t a cathedral but rather a mere chapel.

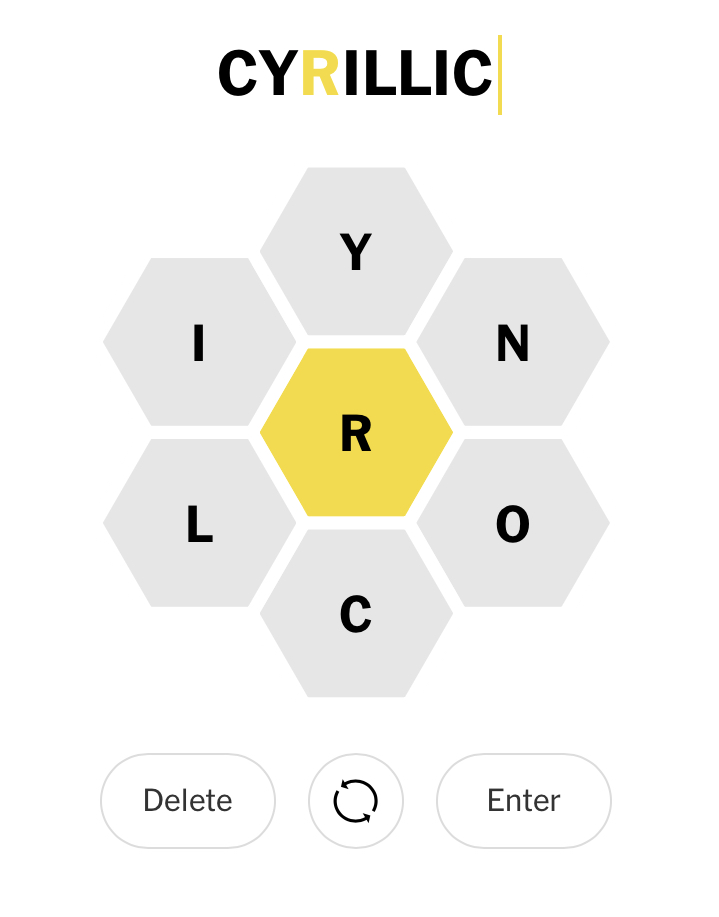

“Not in word list.” Sigh. It’s not that esoteric a word!

Twitter right now is mainly about Twitter but also a little about Mastodon. And Mastodon is mainly about Mastodon but also a lot about Twitter. Both places seem to be pretty chaotic, but here at micro.blog @manton & co. are keeping things smooth and steady. It helps that there don’t seem to be many drama-addicted folks around here.

peaceableness

It is noteworthy, and not in a good way, that an essay by Wendell Berry called “Peaceableness Toward Enemies” — written in response to the 1911 Gulf War — is relevant to the divisions that now exist among Americans. Two passages in particular stood out to me. The first:

Peaceableness toward enemies is an idea that will, of course, continue to be denounced as impractical. It has been too little tried by individuals, much less by nations. It will not readily or easily serve those who are greedy for power. It cannot be effectively used for bad ends. It could not be used as the basis of an empire. It does not afford opportunities for profit. It involves danger to practitioners. It requires sacrifice. And yet it seems to me that it is practical, for it offers the only escape from the logic of retribution. It is the only way by which we can cease to look to war for peace.

Notice how in all these ways peaceableness escapes the abuses inherent in hatred, which always is used for bad ends, always does offer opportunities for profit, etc.

The second should be read with the thought that there are non-physical forms of violence:

Peaceableness is not the amity that exists between people who agree, nor is it the exhaustion or jubilation that follows war. It is not passive. It is the ability to act to resolve conflict without violence. If it is not a practical and a practicable method, it is nothing. As a practicable method, it reduces helplessness in the face of conflict. In the face of conflict, the peaceable person may find several solutions, the violent person only one.

These passages should be read in conjunction with a poem Berry wrote around that time, called “Enemies.”