In Times of Tribulation, Prophecy Books Multiply:

“We are looking for books that not only try to decipher what the Bible is describing, but also how we live now,” says Kim Bangs, editorial director at Chosen Books, an imprint of Baker Publishing. Bangs attributes a greater interest in the End Times to social media, where crises happening around the world are shared. “When you see in real time what the Bible says will happen in the End Times, you start to pay attention and ask questions,” she says. “We seem to be closer to the end than ever before.”

I’m gonna go way out on a limb and say we are unquestionably closer to the end than ever before.

Tonight, I say this to my Republican colleagues who are defending the indefensible: there will come a day when Donald Trump is gone, but your dishonor will remain.

Squirrel wars escalating. I am injured but I persist.

a proper goal

Joel Lehman and Kenneth O. Stanley (2011):

Most ambitious objectives do not illuminate a path to themselves. That is, the gradient of improvement induced by ambitious objectives tends to lead not to the objective itself but instead to dead-end local optima. Indirectly supporting this hypothesis, great discoveries often are not the result of objective-driven search. For example, the major inspiration for both evolutionary computation and genetic programming, natural evolution, innovates through an open-ended process that lacks a final objective. Similarly, large-scale cultural evolutionary processes, such as the evolution of technology, mathematics, and art, lack a unified fixed goal. In addition, direct evidence for this hypothesis is presented from a recently-introduced search algorithm called novelty search. Though ignorant of the ultimate objective of search, in many instances novelty search has counter-intuitively outperformed searching directly for the objective, including a wide variety of randomly-generated problems introduced in an experiment in this chapter. Thus a new understanding is beginning to emerge that suggests that searching for a fixed objective, which is the reigning paradigm in evolutionary computation and even machine learning as a whole, may ultimately limit what can be achieved. Yet the liberating implication of this hypothesis argued in this paper is that by embracing search processes that are not driven by explicit objectives, the breadth and depth of what is reachable through evolutionary methods such as genetic programming may be greatly expanded.

Late in their essay, Lehman and Stanley illustrate their point by describing the navigation of mazes: If you’re going to make your way from the periphery of a maze to the center, you have to be willing to spend a good bit of time moving away from your goal. A determination to go directly towards your goal will “lead not to the objective itself but instead to dead-end local optima.”

(I got to this by following some links from Samuel Arbseman’s newsletter.)

I think this insight has implications far beyond machine learning, and even beyond what Lehman and Stanley call “large-scale cultural evolutionary processes.” It’s true of ordinary human lives as well. When we define our personal goals too narrowly or too rigidly, we render ourselves unable to reach them — or to reach them only to discover that they weren’t our real goals after all.

There’s a wonderful moment in Thomas Merton’s The Seven-Storey Mountain when Merton — a new convert to Catholicism — is whining and vacillating about what he should be: a teacher, a priest, a writer, a monk, something else altogether maybe, a labor activist or a farm laborer. And his friend Robert Lax tells him that what he should want to be is a saint. It’s a marvelous goal not only because all Christians are called to be saints but also because there’s a liberating vagueness to the pursuit of sainthood. In his great essay on “Membership” C. S. Lewis comments that “the worldlings are so monotonously alike compared with the almost fantastic variety of the saints,” and it’s true: there are so many ways to be a saint, and you can never know which of them you’ll be called to take.

I think these thoughts may have some implications for secular vocations as well.

My “productivity system” is … a calendar. That’s it, that’s all I got.

Currently reading: The Women Who Saved the English Countryside by Matthew Kelly 📚

my essential productivity app

… is a calendar. In some seasons of my life it’s a physical calendar, in others a digital one (I’m a huge fan of Fantastical, because it unifies my events and reminders in a single app). Basically I have a task list plus blocked-out periods on my calendar to work on specific projects. For instance, this week I’ve blocked out 8-11:30am every day to work on my biography of Paradise Lost. Also, for both events and reminders I use the Notes and URL fields to add information that will help me remember what specifically I need to focus on. (When I’m using a paper calendar, I jot down such details on sticky notes.)

And that’s it. That’s my “productivity system.” It is very simple and very powerful.

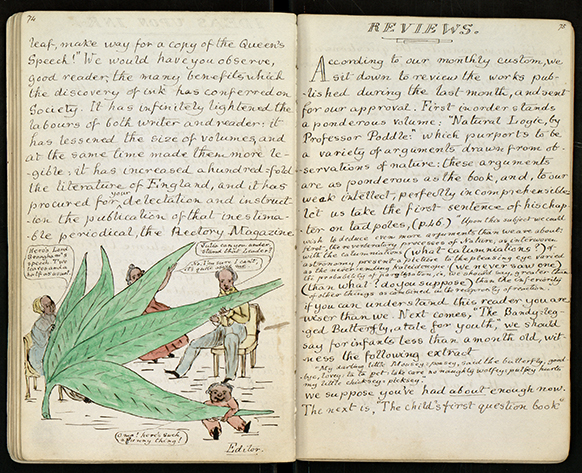

When Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (later to be known as Lewis Carroll) was a child, his father was the rector of the Church of St. Peter, Croft-on-Tees, North Yorkshire, so young Charles created The Rectory Magazine — a sample of which you see above.

Currently reading: Poet of Revolution: The Making of John Milton by Nicholas McDowell 📚

"She's Funny That Way"

“She’s Funny That Way” is a 1928 song composed by Charles N. Daniels, using the pseudonym Neil Moret, with lyrics by Richard A. Whiting — normally a composer himself: “Hooray for Hollywood,” “Ain’t We Got Fun.” But apparently he wrote this lyric for his wife. It’s a great, great song.

A thousand singers have recorded it, but one recording and one only is definitive: Frank Sinatra in 1944. (He recorded it again in 1960, but you can ignore that one — he was already shifting into Chairman of the Board mode, whereas in 1944 he was merely the greatest male pop vocalist of the twentieth century.) Go ahead, have a listen. I’ll wait.

Glorious, isn’t it?

You may have noticed that the song's construction is slightly unusual. Each stanza is comprised of four lines, the third and fourth of them always being “I've got a woman who's crazy for me / She’s funny that way.” You could say that the song is made up of two-line verses each of which is followed by a two-line chorus, or that it doesn’t have a chorus, or that it doesn’t have verses — though it does have a brief bridge in the middle. (Come to think of it, “Ain’t Misbehavin’” is similar.) However you describe it, it’s a classic — and, I think, one of the most neglected entries in the Great American Songbook.

But with all that context in place: I’m here to talk about Art Tatum. Tatum recorded “She’s Funny That Way” at least twice, but I want to focus on one of them, because I think it’s the most perfect jazz recording ever made.

First of all, if you don’t know Art Tatum’s work, you need to understand that (a) he plays almost nothing but standards, (b) he is indisputably the most technically masterful pianist in the history of jazz, and (c) he uses that technique to play those standards in outrageously baroque ways, often amounting to deconstructions of their melodic and harmonic structures. Have a listen to his version of “In a Sentimental Mood,” which he turns inside out about eleven times, twice interpolating “Way Down Yonder on the Swanee River.” It’s nuts.

So with that in mind, please listen to Tatum’s version of “She’s Funny That Way.” Again, I’ll wait.

The first thing you should notice is that for Art Tatum this is remarkably restrained. (It would be pyrotechnical from anybody else.) He never strays far from the melody or the basic harmony. Why he is so restrained I don’t know. But it’s the right choice.

You’ll also notice that he plays it at a much faster tempo than Frank, or anyone else, sings it. It’s a tender, slightly melancholy song, and everyone takes it slow — except Art. So in the first minute he plays the entire song: verse/chorus, verse/chorus, bridge, verse/chorus. And then, precisely at the one-minute mark, he starts to get down.

Maybe you’ve heard of stride piano? If you want to know what it is, just listen to what Tatum is doing with his left hand here. That bassline walking — no, it’s striding, it’s even strutting. One of the fathers of stride piano is James P. Johnson, who taught Fats Waller, who inspired Tatum. Tatum ended up playing with a harmonic and rhythmic complexity that neither Johnson nor Waller would have understood or maybe even liked, but he never lost the love of that stride bassline. (He even uses it in his version of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” the melody of which he starts deconstructing in the first bar.)

That stride rhythm anchors him for most of the rest of the song — even when you think he’s left it behind he slyly brings it back — and that anchor I think keeps him on the melody as well. Oh, to be sure, he's glissando-ing up and down the keyboard at supersonic speed, and elaborates a series of melodies-within-the-melody — listen to the delightful little run at about 1:51 — but you never lose track of where you are.

Around 2:03 he turns the whole song into — well, almost a barrelhouse number. You’d think that wouldn’t work with this intimate love song, but it’s awesome.

Even though the stride rhythm keeps going, and he’s flickering all over the top half of the keyboard, increasingly there’s some funny stuff going on in that left hand. He starts playing these rapid block chords that often go down when the melody is going up, and vice versa. Listen to around 2:40, for instance, when he’s playing the bridge again. Vertigo-inducing. But then he’s back to that joyous semi-barrelhouse.

At 3:09, with a booming note in the bass, he slows the stride rhythm, and as he moves towards the conclusion deploys some complex harmonies to remind himself and us that it’s a kind of art song he’s playing. Starting at 3:27 he breaks the rhythm; then, at 3:39, another booming bass note tells us that he’s about to recapitulate … and he does — but just when you think he’s about to return us to the tonic, hit us with that final chord (3:41), he has one more little trick to play: an absolutely delightful 23-note run up the keyboard that’s basically a variation on the theme, concluding with the last two notes of the original melody played up high, like a little signatory “Ta-da!”

It’s a work of genius, absolute perfection. If you were to ask me “What is jazz?” — I would just play you this song. It encapsulates everything that makes jazz the great American art form.

Here’s a little thing I often think about: On “The Weight” Garth Hudson is on piano, and as each chorus approaches he plays a little country-blues-gospel fill. Then he plays another fill after each line of the chorus. The chorus has three lines, and there are five choruses in the song, which means that he plays twenty of those fills — and no two of them are the same. It’s like a condensed encyclopedia of piano riffs.

How to give university lectures | Mary Beard:

The second [lecturing tip I picked up from colleagues] was from Keith Hopkins, who asked students at his first lectures on the Roman empire: What was the most important thing to happen in the reign of the emperor Augustus? All kinds of answers came in, from the “settlement of 27” to the return of the Roman standards from the Parthians. You could bet anything, he used to say, that no one (not even the committed Christians) would say “the birth of Jesus”. He used this to point out to them how narrow their vision could be, and how rigid the boundary was between the history of Rome and the history of Christianity, even though they were part of the same world.

This is a fascinating point in itself, but it reminds me that Hopkins was notorious for his frustration with academic lecturing, in all venues. He felt that very few academics took seriously their responsibilities to their audiences — or, really, were even aware that they have such responsibilities. Long ago a British academic told me about listening to a lecturer drone his way through an hour, never looking up from the paper in front of him, basically talking into his chest. As it happens, Hopkins was also in the audience. At the Q&A time, Hopkins stood up and said, “I have three reactions to your talk and the first is boredom.”

Just ordinary morning light, that’s all. But I like it a lot.

Pretty typical message to my wife, who’s in Alabama with family

Currently reading: London: A Social History by Roy Porter 📚

normie wisdom 4: quirky vs. basic

Right now, our society demands you be a Special Snowflake. Women who aren’t quirky enough are “basic bitches”, men who aren’t quirky enough are “yet another straight white dude”. Just today, I read some dating advice saying that single men need to develop unusual hobbies or interests, because (it asked, in all seriousness) why would a woman want to date someone who doesn’t “stand out”?

Someone on Twitter complained that boring people go to medical school because if you’re a doctor you don’t need to have a personality. Edward Teach complains that people get into sexual fetishes as a replacement for a personality. I’ve even heard someone complain that boring people take up rock-climbing as a personality substitute: it is (they say) the minimum viable quirky pastime. Nobody wants to be caught admitting that their only hobbies are reading and video games, and maybe rock climbing is enough to avoid being relegated to the great mass of boring people. The complainer was arguing that we shouldn’t let these people get away that easily. They need to be quirkier!

A friend read an article once about someone who moved to China for several years to learn to cook rare varieties of tofu. She became insanely jealous; she doesn’t especially like China or tofu, but she felt that if she’d done something like that, she could bank enough quirkiness points that she’d never have to cultivate another hobby again.

In this kind of environment, of course mentally ill people will exploit their illness for quirkiness points! We place such unreasonable quirkiness demands on everybody that you have to take any advantage you can get!

What the West Got Wrong About China – Habi Zhang:

The reason why China would brazenly “disregard the international law” that many other nations voluntarily abide by is that the rule of law is not, and has never been, a moral principle in Chinese society. […]

It was the rule of morality, not the rule of law, that defined Chinese politics.

In The Classics of Filial Piety — primarily a moral code of conduct — Confucius teaches that “of all the actions of man there is none greater than filial piety. In filial piety, there is nothing greater than the reverential awe of one’s father. In the reverential awe shown to one’s father, there is nothing greater than the making him the correlate of Heaven.” We can therefore conclude that the Durkheimian sense of the sacred object — the source of moral authority — is the father in both the literal and metaphorical sense. With this understanding, Confucianism can be viewed as a religion as manifested in the ritual of ancestor worship.

What the individual sovereignty is to liberalism, ancestor worship is to Confucianism.

Fascinating. James Dominic Rooney offers a partial dissent here — though it’s not to my mind especially convincing. David K. Schneider weighs in on the debate and comes down more on Zhang’s side: “liberal government is antithetical to the Confucian ideal of benevolent government. In Mencius, the happiness of the people is the measure of good government. But the people are not sovereign. Only a king is sovereign and conformity with Heaven’s ritual order is the responsibility of an educated political and economic elite, which is charged with the duty of acting as parents to the people, who in turn are obliged to submit.”

This argument sheds an interesting light on my recent essay on “Recovering Piety.”

I wish there were a larger version of this response by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to an autobiographical questionnaire. The eye is drawn to his joking response to “If not yourself, who would you be?” — but I like his answers to “What characters in history do you most dislike?” (“Very tolerant to them all”) and to “What is your present state of mind?” (“Jaded.”)