I do not criticize Josh Wardle, who deserves to get paid for his work — and I can’t even imagine what his hosting costs are — but I’m sorry to see this. When a small endeavor gets bought out by a big media company it is invariably bad news for the people who enjoy that small endeavor. How long, for instance, before every Wordle page is surrounded by ads on three or all four sides? Or before the game goes behind a paywall? Or, more likely, both?

UPDATE: Counter-take from Kottke here, which I don’t fully agree with, but I do resonate with one person he quotes: “the reality that supporting a small scale thing of beauty at large scale is beyond one person (now) & reasonable options are compromised … is bittersweet.” More “unfortunate” than “bittersweet,” but yes.

Currently reading: Index, A History of the: A Bookish Adventure from Medieval Manuscripts to the Digital Age by Dennis Duncan 📚

Newsletter: Harmonies and Dissonances.

excerpt from my Sent folder: dominant

Anyway, don't you realize that yesterday was a fantastic result for the USMNT? I read our coach's comments. He said we were "dominant." He said that the Canadians "couldn't handle our physicality." Frankly, I don't see how things could possibly have gone better.

(To me, in all seriousness, these sound like the comments of a man whose job is hanging by a thread and in my judgment ought to be hanging by a thread — at best. In fact, that press conference alone is a justification for sacking.)

Currently reading: The Time Machine by H. G. Wells 📚

eating people is wrong

I’m sure what I’m about to say has been said by many before me, but I’m counting on Adam Roberts to let me know about that.

Early in H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds, our narrator comes across an artilleryman who seems to be the only survivor of his company, which was otherwise obliterated by the Martians’ heat ray. The two men part, but then near the end of the book meet again, and by this time the artilleryman has done some thinking. He has decided that direct confrontation of the technologically superior Martians will be fruitless — “This isn’t a war…. It never was a war, any more than there’s war between man and ants” — but that some other form of resistance might, over the long term, work. He imagines a future in which the Martians keep some human beings for … well, he doesn’t know what for. He does not suspect what our narrator has learned, that the Martians want humans for food. But in any case, he is sure that the majority of people will meekly welcome their new Martian overlords. But, he also thinks, other, more determined and resourceful, humans will move underground to build a resistance movement, will avoid the Martians and bide their time, will read books and study science and grow in knowledge and power — until they are ready to strike back.

Meanwhile, in The Time Machine (written a couple of years earlier) Wells imagines a far future in which humanity has branched into a passive, infantile race bred for food and a second race that lives a more active and technologically sophisticated life underground — and of course eats the others.

What if we were to imagine a coherent H. G. Wells Fictional Universe in which both of the stories are true? At the end of The War of the Worlds the Martian invaders die from exposure to microbes, against which they have no defenses, but the Martians are a technologically advanced civilization and apparently in great need of a better life environment — Mars is dying — and more reliable sources of food, so one might very well infer that they learn from their unsuccessful first invasion and on a second attempt achieve their aims, setting up precisely the kind of social arrangement the artilleryman envisions, just with the meek obedient humans as their chief food. Suppose that this arrangement lasts hundreds of thousands of years, during which time the humans used for food become increasingly docile and infantile – a development accelerated and intensified by selective breeding – while the underground resistance gradually becomes better adapted for life in the dark. Eventually the Martians die, or are killed, or depart for more attractive planetary alternative, but by that point the two halves of humanity have taken such different evolutionary roads that they seem and perhaps reproductively are different species – which means that the Morlocks feel that no taboo is violated if they replace the Martians as apex predator and continue the practice of raising Eloi for food.

It all fits, I think.

Again, surely earlier readers and critics have already made this point; and in any case almost every reader of Wells knows that he’s obsessed, at this stage in his career, with selective breeding and eugenics. Thanks to certain prominent figures, these themes were omnipresent in late Victorian culture. (Later also: they’re essential to the projects of Morgoth, Sauron, and Saruman in The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion.)

But the rise of hopes and fears surrounding artificial intelligence has been accompanied by the decline of the hopes and fears surrounding eugenics. Gattaca gives way to A.I. and then Ex Machina; Ishiguro writes Never Let Me Go but then, fifteen years later, Klara and the Sun. Why go through the lengthy trouble of breeding humans to be slaves when one can manufacture slaves? So can the themes of eugenics and selective breeding of humans still have the claim on our imagination they once had?

ADDENDUM

- Stories about the breeding of slaves often feature the possibility, or the actuality, of a slave revolt -- but not in Tolkien. The orcs and other creatures bred by Morgoth/Sauron/Saruman may fail in various ways, but they never rebel. The possibility of a robot revolt, by contrast, seems to have been baked into the conception right from the beginning.

- The 20th-century fear of selective human breeding was sustained, in the West, by the wars of that century: First the Nazis were thought to be breeding Supermen, then, when the World Wars gave way to the Cold War, the new object of such fears became the Soviet Union. (And the fears weren’t simply manufactured: I remember stories of the American women swimmers in the Olympics hearing the baritone laughs and shouts of the testosterone-filled East German women in the next locker room.) Maybe the collapse of the Soviet system inevitably led to a diminishment in the anxieties associated with eugenics: no more Ivan Dragos, no more Winter Soldiers, no more Black Widows.

- In the reading of The Time Machine in his superb literary biography of Wells, Adam Roberts comments on the moment when, assaulted by Morlocks, the Time Traveler loses his little Eloi friend Weena: “I searched again for traces of Weena, but there were none. It was plain that they had left her poor little body in the forest. I cannot describe how it relieved me to think that it had escaped the awful fate to which it seemed destined.” To this, Adam says, “Better burned alive than raped by Morlocks, it seems.” But surely the Traveler means eaten by Morlocks. Which raises a question I hint at in the main body of this post: Have the Eloi and Morlocks taken such divergent evolutionary paths that the Morlocks could no longer think of the Eloi as objects of sexual interest? I am inclined to think so. After all, the taboo on interspecies sex and the taboo on cannibalism are in a sense mutually exclusive. If you can eat it, you can’t have sex with it; if you can have sex with it, you can’t eat it.

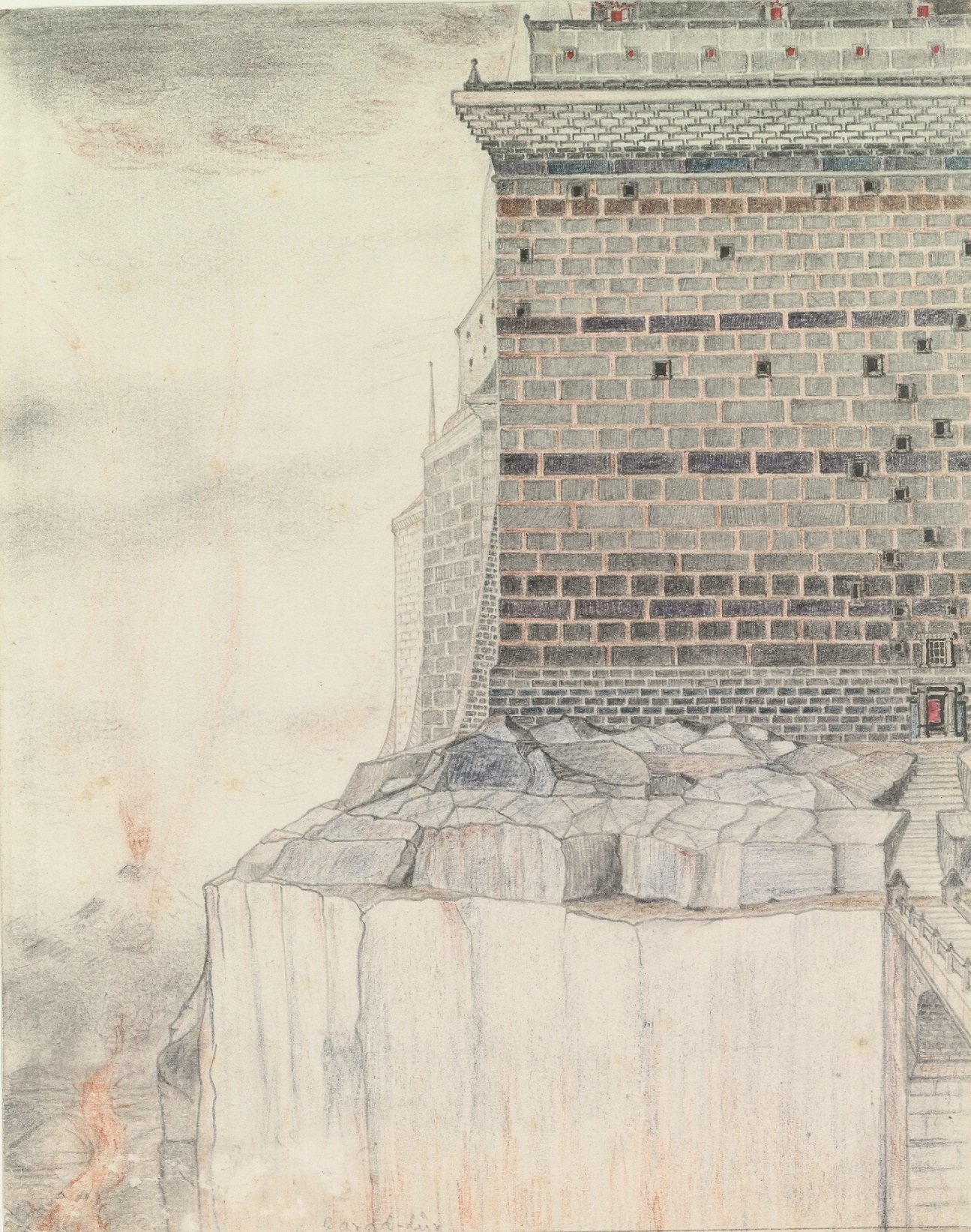

Tolkien’s own drawing of Sauron’s fortress Barad-dûr, with Mount Doom in the distance.

If Christians are ever again taken seriously in this country, it won’t be because they own the libs and rout the woke; it won’t be because they triumph over their enemies and enjoy the spoils of victory; it will be, it only will be, because Christians act like this. There is one Way. And whether we take it is our only truly meaningful choice.

In the wake of the 2016 election, Trump claimed to have had higher turnout at his inauguration than Barack Obama did. Subsequent polls and surveys presented people with pictures of Obama and Trump’s inauguration crowds and asked which was bigger. Republicans consistently identified the visibly smaller (Trump) crowd as being larger than the other. A narrative quickly emerged that Trump supporters literally couldn’t identify the correct answer; they were so brainwashed that they actually believed that the obviously smaller crowd was, in fact, larger.

Of course, a far more obvious and empirically plausible explanation is that respondents knew perfectly well what the correct answer was. However, they also had a sense of how that answer would be used in the media (“Even Trump’s supporters don’t believe his nonsense!”), so they simply declined to give pollsters the response they seemed to be looking for.

As a matter of fact, respondents regularly troll researchers in polling and surveys – especially when they are asked whether or not they subscribe to absurd or fringe beliefs, such as birtherism (a conspiracy that held that Barack Obama was born outside of the US and was legally ineligible to serve as president of the United States).

This is an absolutely vital point.

Well, this was different.

⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜

🟩🟨🟨🟨🟩

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

Currently reading: The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells 📚

I sort of hate my office, but I just yesterday (after eight years!) realized that the windowsill makes a decent standing desk.

Currently reading: The Road to Middle-Earth: How J.R.R. Tolkien Created a New Mythology by Tom Shippey 📚

scouring

In one of his Prefaces to The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien notes that many early readers of the book thought that the chapter called “The Scouring of the Shire” is a kind of commentary on the rigors of the immediate post-war years of what David Kynaston has called “Austerity Britain.” No, Tolkien insisted, it is not; that chapter “is an essential part of the plot, foreseen from the outset.” That is, from the beginning of his tale he had foreseen what the dominance of Sauron (and Saruman) would mean for the Shire, and had understood that, should that domination be overcome, some kind of reckoning would be necessary.

That reckoning takes the form of a “scouring,” and you should always pay attention to Tolkien’s words, especially when they are in any way unusual. He could have said “cleansing” or “purification” or could have invoked a very different image for putting things right.* But scouring is what we do to something that is not just dirty but has become encrusted — to a surface to which something foreign (old food, rust) has become affixed and cannot easily be removed. Scouring requires strenuous effort because the foreign object is highly resistant to removal — it seems to want to remain. And the foreign material obscures the intrinsic character of the object: the shining thing cannot shine.

And so when faced with an object that requires scouring we are tempted, sometimes, to throw it away and start over — to give up on it. But let’s look a little deeper into the word. The OED tells me that there are closely related terms in other European languages and that they all trace back to a key Latin word: cūrāre, care (from which we also get “cure”). Scouring is ex + cūrāre, to care for something by cleaning it out. To cure it. To return it to its proper cleanliness and shine and gloss.

To repair it. And the hobbits have to repair the Shire because it is their home. Starting over is not an option.

As everyone knows, the hero’s journey culminates in a nostos, a homecoming. One of the other interesting things the OED tells me is that repair as a noun may have this meaning:

return, return home, place one returns to, residence, home, abode (c1100 in Old French), meeting (12th cent.), place (13th cent.), visit, visiting, frequenting (13th cent.), place of refuge, refuge (14th cent.) … Compare post-classical Latin repairium, reparium, reperium harbour, haunt, resort

Such a network of meanings survives for us, if at all, only as a comic archaism: Let us repair to the pub for a restorative draught! But they were once central to this word, not only in its noun forms but in its verb forms as well:

Anglo-Norman repeirer, reparier, repairir, etc., Anglo-Norman and Old French, Middle French repairier, Anglo-Norman and Middle French repairer, reparer, Middle French reperer ... to return, go back, to go home, to head for, to go, to arrive, (of memory, strength, etc.) to return (also reflexive; end of the 11th cent.; also c1100 as repadrer), to dwell, reside, stay, to frequent (12th cent.)

We could say, then, that at the end of The Lord of the Rings the hobbits repair to the Shire to repair it.

There is in both scouring and repairing a strong suggestion of restoration: of bringing something back to its ideal condition and proper function. (Not always, but sometimes — and this is a point I want to return to — the restoration is accomplished less by what we do than by what we refrain from doing. Thus Shakespeare in Cymbeline: “Mans ore-labor'd sense Repaires it selfe by rest.” Milton in Samson Agonistes: “Secret refreshings, that repair his strength.”) When we are away from home, home naturally falls into disrepair; and does so even more quickly if it is not left alone but rather is despoiled by those who do not love it. This can be seen as vividly in the Odyssey as in The Lord of the Rings.

A question to ask myself: What do I despair of repairing? I would rather discard than scour. Scouring is a lot of work for an uncertain result. But I will do it for anything and anywhere I think of as my harbor, my place of refuge — my home.

- Since writing this I have learned, from Volume IX of Christopher Tolkien’s History of Middle-Earth, that his father’s first title for this chapter was “The Mending of the Shire.” For obvious reasons I like “Scouring” better.

trying

About to watch the USMNT v. El Salvador, and having a thought: When you watch a well-managed team, you can easily see what the team is trying to do, how they’re trying to play. This is true for very successful teams (Liverpool) and intermittently successful teams (Leeds) and struggling teams (Burnley). Half an hour of close observation is enough to show you what the plan is.

Since Gregg Berhalter took over the USMNT, I have watched every competitive match, and I have no idea what he wants the team to do, how he wants them to play. They may win, lose, or draw tonight but I doubt that I will be able to figure out what the plan is.

We are used to plaintive cries that not enough students opt for scientific subjects, and related worries about the supposed drift of our culture towards an anti-scientific relativism or, ultimately, a post-truth mentality. But one of the things we have learnt in the past ten months is that we set ourselves up for profound confusion if we talk about “science” as a source of self-evidently clear and effective solutions, as if narratives and values played no role. Bland claims to be “following the science” have acquired an unhappily hollow sound. […]

What does it mean to “fail our children” in this broader context? It means backing away from the scale of change that we face, and from the job of resourcing young people to respond with intelligence, imagination and honesty. It would be ridiculous to pretend that there are a few simple restructurings that will achieve this. We need a courageous rethinking of our ingrained assumptions about education. We need to pay some critical and sympathetic attention to those despised and frequently attacked parallel worlds of the Montessori and Steiner systems. We need the issue of resources for the human spirit to be at the heart of educational vision – including craft, drama, sport, exposure to the raw natural world, community service. And anyone who thinks this is somehow in tension with responsible scientific training has not understood either sciences or humanities.

Those with ears to hear, let them hear.

Currently reading: Early Christianity and Greek Paideia by Werner Jaeger 📚