Americans talk right now as if everything is disappointing and life is bad. And we need to understand that as a society — not just America, but Western societies generally — we’re getting what I think is the greatest single gift in the entire history of humanity, except maybe medical care. That’s the gift of 10, 15, sometimes 20 years of additional life in the most satisfying and pro-social part of life: late-adulthood.

We’re talking about a world in which people well into their eighties will be healthy enough to work, to contribute, to mentor, to coach. We’re getting a period of fantastic personal growth and development, right at the time in life when we’re best able to exploit it.

This is an incredible thing when you think about it. In many cases, people in history didn’t live long enough to experience this upturn in life satisfaction. So the challenge is to accept this gift, not to throw it away with age discrimination or by forcing people to retire or leave the workforce because supposedly there’s no role for them in their community.

I wrote about Paul Kingsnorth and the SCT.

I just discovered the World Encyclopedia of Puppetry Arts.

An oddity of musical recording: Records can sound quite different on CD & streaming & vinyl because they’re mastered differently for different media. That noted: the North Mississippi Allstars album Set Sail sounds better on vinyl than any record I’ve heard in a long time. It’s a terrific record, but the engineering is astonishing. If you’re gonna listen to just one song, make it “See the Moon.”

The nightmarish 1936 North American cold wave was soon followed by the nightmarish 1936 North American heat wave. California’s escape from both must have increased its desirability as a settling-place.

Silver pair-cased verge escapement watch with silver sun and moon dial by Humphry Adamson, London; from the Clockmakers' Museum.

Angus is reassured by my return.

The bokeh on the iPhone camera’s Portrait mode looks just awful. But on the positive side, after a week in the North it’s nice to return to find that Spring has sprung in Waco.

The correspondence of Dorothy L. Sayers and … Ezra Pound.

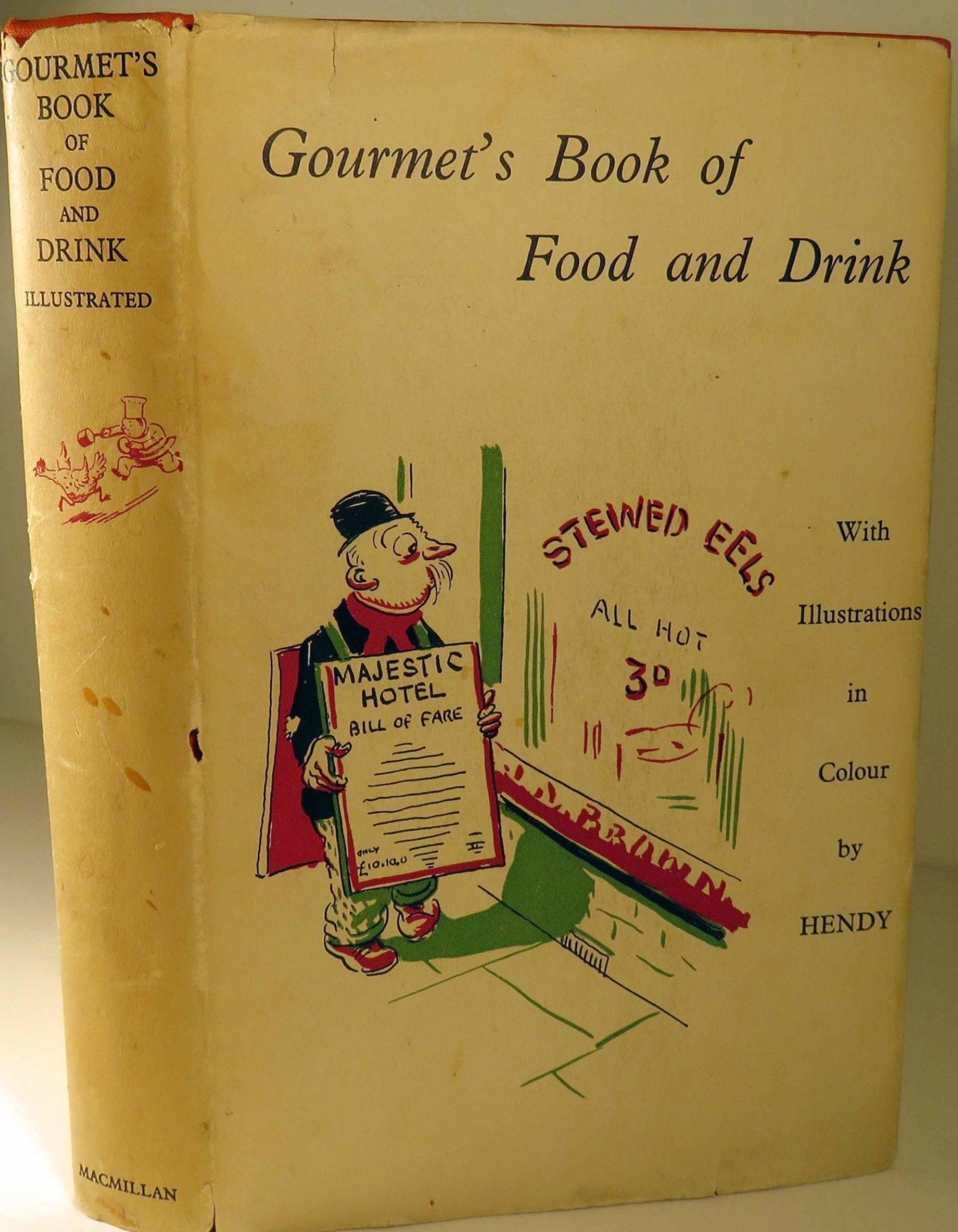

This book was written by Dorothy L. Sayers’s husband, Atherton “Mac” Fleming, and indeed was dedicated to her. (“To my wife, who can make an omelette.") At Christmas 1931 she sent a copy to G. K. Chesterton, who replied:

Will you please thank your husband a thousand times for thinking of trusting so rich and impressive a monograph to me — who who alas cannot cook or do anything useful: but only eat — and drink — and give thanks not only to God but my more creative fellow creatures: the great Craftsmen of the Guild and Mystery of the Kitchen. I hope he will forgive me if I do not thank him directly — or rather thank you both collectively — but I suppose I must wait a little while before you publish a companion volume, containing all the best ways of poisoning the foods he is so expert in preparing.

Y’all know how much I love to see my former students go on to do cool things. Today, working in the Wade Center, I ended up sitting next to my former TA Aubrey Buster! Now she’s a serious scholar of Second Temple Judaism and many other things I know little or nothing about.

When people critique “capitalism,” they usually mean one of two things:

- The currently dominant system of international free trade and global supply chains

- Greed

Usually it doesn’t take long to figure out which one they have in mind.

“Brilliance in controversy is a corrupting accomplishment. Always to play to win is to take one’s standards from one’s opponent, and local victory comes to displace every other consideration.” – Michael Oakeshott