An excerpt from Nick Carr’s outstanding new book:

In their early form, online social networks reflected, at least by analogy, traditional patterns of socializing. Their design maintained divisions of space and time. Each member of a network had his or her own “place,” in the form of a profile page, and people traveled, through hyperlinks, from place to place to “visit” friends. Status updates and other postings were arranged chronologically. They unspooled sequentially through time, as thoughts and experiences had always unfolded. When Facebook introduced its automated News Feed in 2006, it replaced the familiar structure of the social world with the logic of the computer. It erased the divisions and disrupted the sequences, removing social interactions from the constraints of space and time and placing them into a frictionless setting of instantaneity and simultaneity. Socializing in this new sphere follows no familiar, human pattern; it vibrates chaotically to the otherworldly rhythms of algorithmic calculation.

The consequences have been dreadful — as we all know, though sometimes we try to pretend otherwise.

Is any group of people more self-deluded than committed multitaskers?

Nass assumed that people would stop trying to multitask once shown the [detailed, irerefutable!] evidence of how bad they were at it. But his subjects were ‘totally unfazed,’ continuing to believe themselves excellent at multitasking and ‘able to do more and more and more.’ If individuals in a controlled experiment are this oblivious and refuse to change when confronted with proof of their shoddy performance, then what hope do the rest of us have as we wade through the daily sea of digital distractions?

Over at Mockingbird, where they usually feature trashy pop music and dumb movies, I’ve decided to bring some class to the joint by writing on spells, prayers, and RICHARD WAGNER. It’s still a very Mockingbirdy post, though.

I continued my series on the family and its challenges with a post on contractualism.

I’ve hiked down from the (offline!) mountaintop to handle some business, so while I’m here I’ll post a few things and then be largely cut off from the world for the next few days. There’s a chance of SNOW later this week and if I got marooned in my Hill Country retreat with just my books, my guitar, and a fireplace with plenty of firewood … well, I wouldn’t be too upset.

What 15 Very Different People Hope to See in 2025 | NYT:

Colson Whitehead: “I have no hopes for 2025. Humanity is disappointing. We killed the Earth. Villains triumph and the innocents suffer. I imagine these trends will continue.”

Also works for every year.

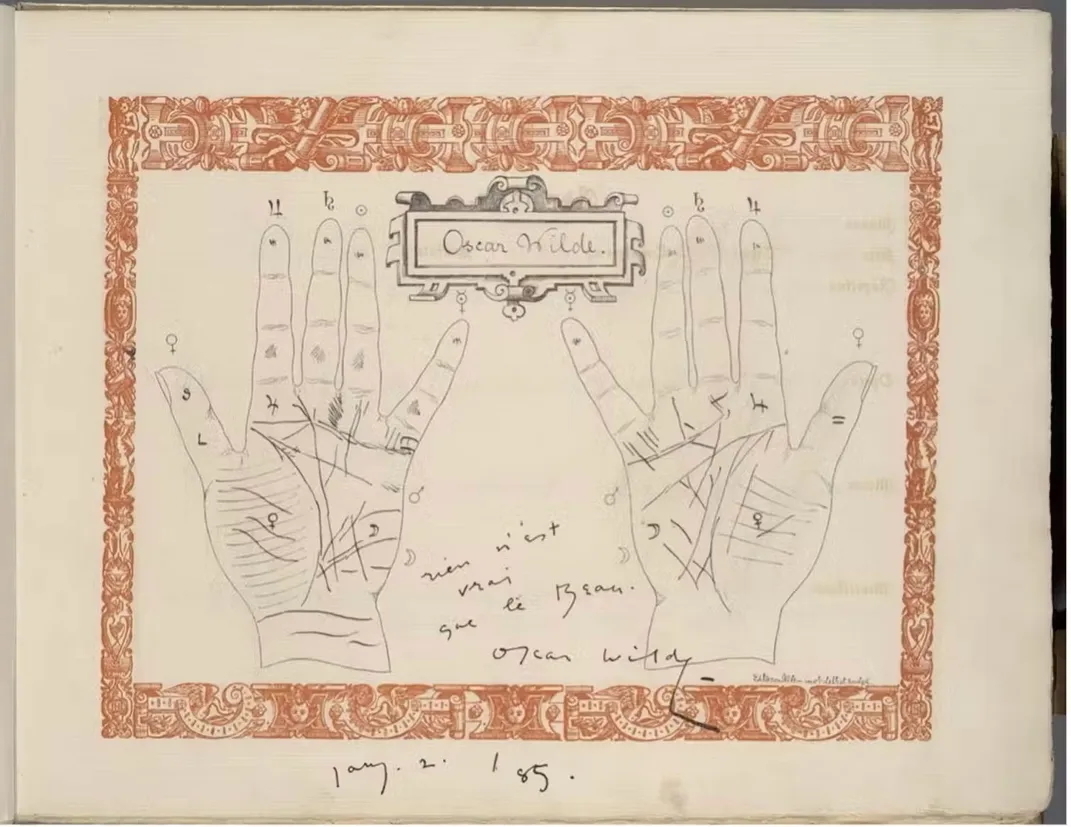

Oscar Wilde had his palms read — and sketched.

I quit Netflix six or seven years ago, and would never have come back … but when I learned that they’re doing Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl … well. If they’d charged me fifty bucks I’d have signed up immediately. Watched it tonight and it’s a masterpiece. 🎞

One of the best things I did last year was to inspire a couple of Austin Kleon’s collages.

Lo, how a rose … and Angus photobombing it

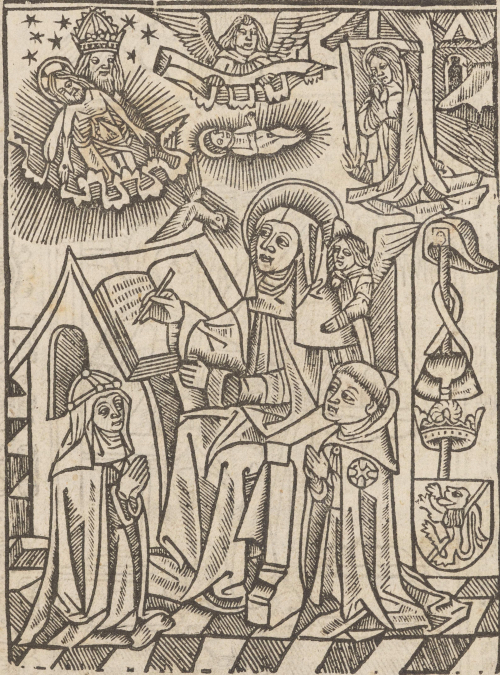

St. Birgitta writing out her account of the Nativity. She seems to have been an exceptionally large woman.

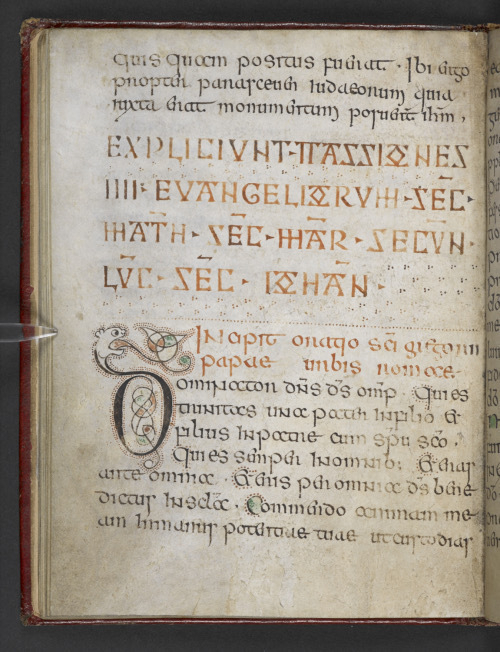

A Gospel page from the Nunnaminster Book

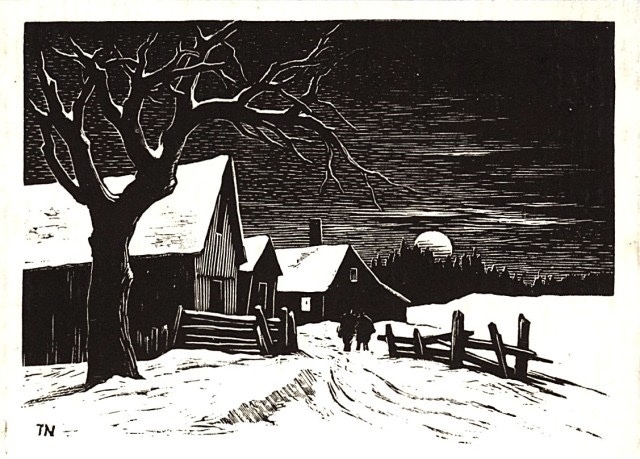

Thomas W. Nason, illustration for Donald Hall’s Here at Eagle Pond (1990).

Re-upping from a year ago today: Why I don’t keep track of how many books I read.

Do yourself a favor and listen to the incomparable Ella sing “What Are You Doing On New Year’s Eve?”