The great Shannon Mattern on cardboard boxes.

I wrote about a forthcoming essay of mine — and (more important) about a forthcoming novel that reveals some massive implications of my essay that, before reading it, I had not considered.

I have to give Apple credit here: the video is boldly telling us the truth. Other companies hide their true agenda, or even – if they have real competition – occasionally try to make things better for customers. But Apple’s globe-spanning monopoly gives it that walk-away scale of money and power that allows it to say – and then do – whatever it wants. For a totalizing company like Apple and the other Big Tech beasts, anything that stands in the way of the company’s dominance must be destroyed. You like playing the guitar for friends on the beach? No. Use a screen instead. You enjoy reading print books, which don’t spy on you as you read them? Not acceptable. Use a screen. Do you value being creative, or social, or just living a moment of your life off the screen? Get over it. Everything else will be destroyed. Only screens will remain.

the archetypal future

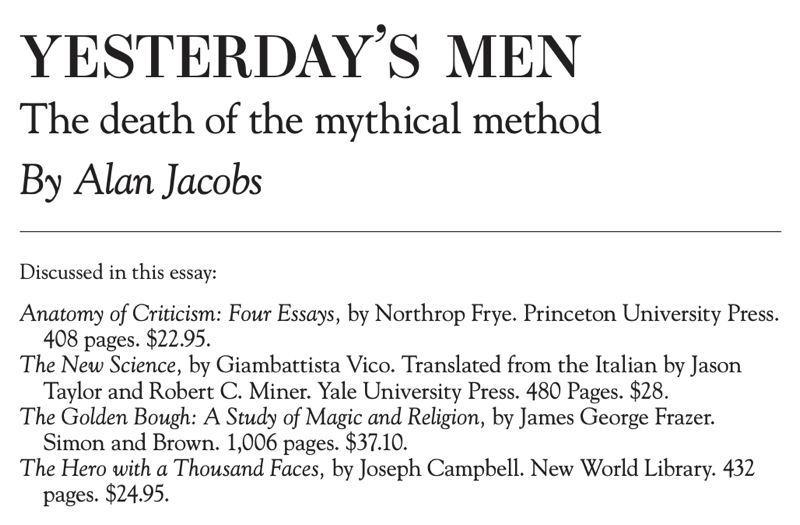

Next month I have an essay coming out in Harper’s called “Yesterday’s Men: The Death of the Mythical Method.” In it I look at the rise — a rise that started a looong time ago — of myth as the central category of discourse among poets, novelists, and humanities scholars; and then I look at the rapid decline of that category and its replacement by others. (Spoiler: the replacement categories are, mainly, overtly political.) Then, near the end, I ask whether “the mythical method” — a line I borrow from T. S. Eliot — has any literary future.

But along the way I also talk about the places where the language of myth and archetype still survives, and even thrives: in movies, for instance, and in many forms of what academics call “genre fiction.” A form of discourse, a vocabulary, a set of terms and images, might be passé in the academy without having lost its power elsewhere. (A fact that academics try not to notice.)

And here’s another implication of my essay, one which I have only since writing it become aware of: If, as celebrants from Vico to Northrop Frye and Joseph Campbell have said, myths and archetypes are deeply and pervasively embedded in all our cultural productions — and pause for a moment to reflect on the enormous significance of this — then, per necessitatem, they are also deeply embedded in our large language models. Which means, first, that GAI endeavors will be thoroughly shaped by those myths and archetypes; and second, that if human beings are able to create artificial general intelligence, if the Singularity really does happen, then it will be foundationally constituted by those very myths and archetypes.

Had you thought of that possibility? I hadn’t … until I read Robin Sloan’s delightful soon-forthcoming novel Moonbound, whose own spectacular narrative is generated by the double thought that (a) human beings are creatures made of myths and (b) whatever succeeds us twelve thousand years from now — however strange to us, and whether biological or digital or both — will be made of the same myths.

Put that in your pipe and smoke it. I’m having a nice long toke even as I write.

P.S. If you want to get a little deeper in the weeds re: AI and myths, read this characteristically smart post by Samuel Arbesman.

Auden’s The Shield of Achilles gets a starred review from Publisher’s Weekly.

temporary storage

Drafts is a fantastic app, so well-designed, so capable, so powerful. For my money it’s the best “bucket” app, ideal for holding onto chunks of text.

But I have a problem: I put things into Drafts and then forget about them. Yes, I tag them, but that doesn’t help. They just disappear into the bucket.

Which is why over the past few months I’ve been using Tot. I bought Tot when it first came out, but didn’t use it much. Now it’s vital to my organizational system. Here’s why: it has a single window with seven tabs, each tab a different color. That’s it. Seven is all you get.

And that’s what I love about Tot. I put things there and they’re easy to find; and when I’ve filled all the tabs, I have to decide whether (a) to delete something or (b) to put it into an proper text file to make something useful of it — a blog post, a reminder, a note for my students, whatever.

This is yet another situation in which I’ve learned to make friction my friend. Drafts is absolutely frictionless, brilliantly so, but for whatever reason my mind doesn’t thrive in frictionless conditions. Back to the rough ground!

try not to think

Fraudulent academic papers are on the rise, and will continue to be on the rise as long as academics substitute counting for judgment. The fetish for sheer numbers of publications should have ended decades ago, but the professoriate can’t confront its addiction, or accept its responsibility for creating this vast system of perverse incentives. It’s always interesting to see what elements of their wobbly structures academics are simply unable to reconsider, no matter how dire the situation. In this case, I think people who have climbed the greasy pole to tenure can’t bear the thought that some younger people might be less miserable than they and their cohort were.

I always like to remind people that the real, legal, birth-certificate name of Blossom Dearie was … Blossom Dearie.

Austin Kleon’s great newsletter edition on the objects we love and live with reminds me that we still use our metronome, some sixty-plus years after Teri’s mom bought it.

The most Arsenal thing ever would be for Spurs to beat Man City today and then Arsenal lose to Everton on Sunday. ⚽️

This by Rob Chapman is one of a zillion videos encouraging me to ask whether I’m a beginner, intermediate, or advanced guitar player. “Beginner” is a bad word here, because no one who has been playing for a long time (in my case, 20 years) can properly bre called a beginner. The better word is basic. Also, I think “advanced” should be distinguished from “professional.” So I think we need five categories:

- beginner

- basic

- intermediate

- advanced

- professional

I think I’m a basic/intermediate player, and will probably not get much better. It’s hard to progress when you start an instrument in your forties, and I have the added handicap of some permanently damaged fingers on my left hand (thanks to a habit, common among basketball players, of breaking them and then not having them properly set). But it would be silly to call myself a “beginner.”

By the way, if I could belong to one of the London livery companies, I would certainly choose the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers.

If you happen to be a Freeman or Freewoman of the City of London, then you may exercise your ancient right to take sheep across London or Southwark Bridge without paying a toll. That right is protected by the Worshipful Company of Woolmen, so now you know whom to thank.

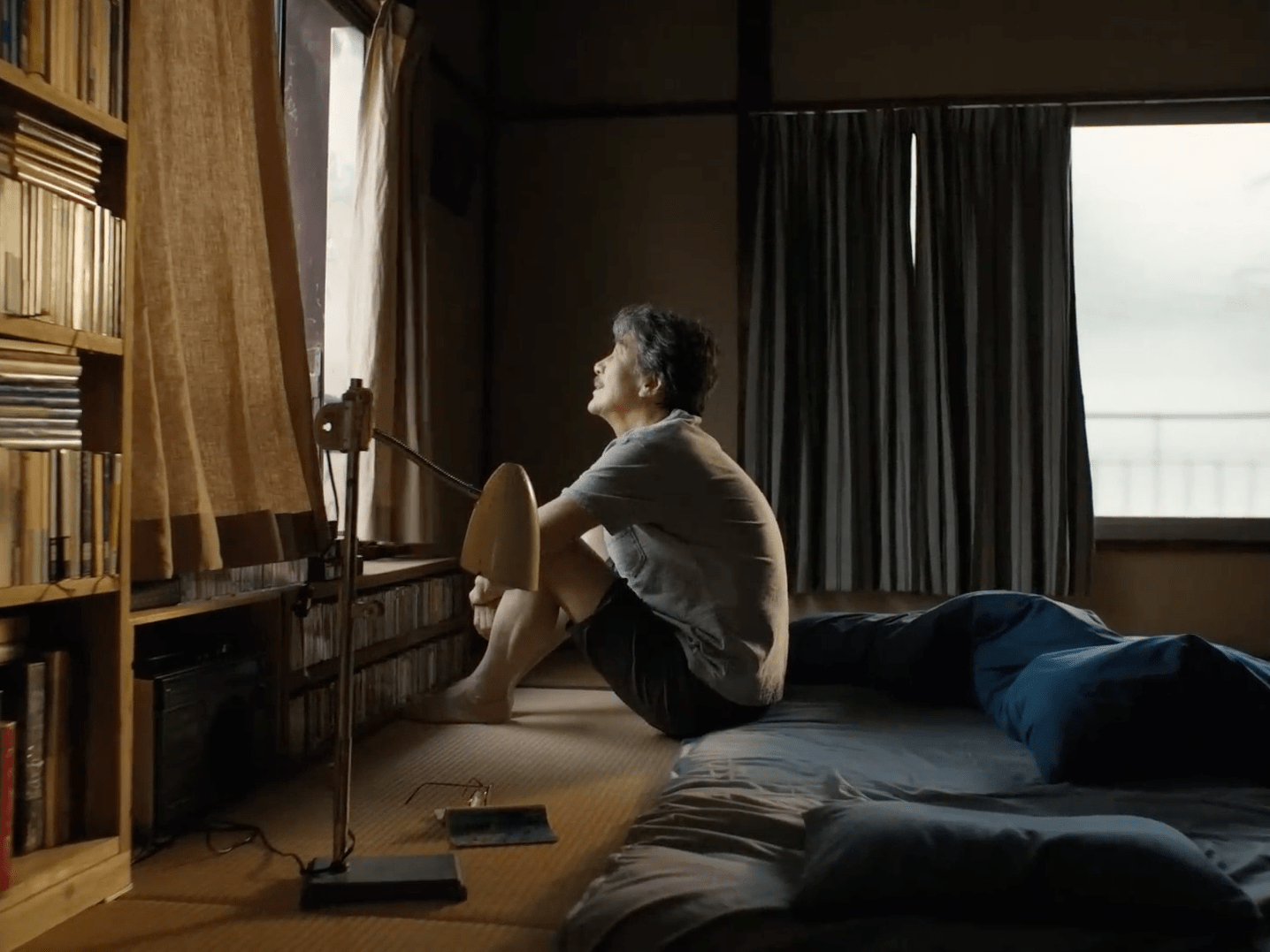

Perfect Days

The Richard Brody review of Perfect Days is a tone-deaf review by the most reliably tone-deaf reviewer out there. Every reviewer has limits to his or her catholicity of taste, because every human being is thus limited, but Brody’s cinematic sweet spot seems to be tiny, and when he doesn’t like a movie he simply doesn’t pay attention to it. I just don’t think Brody likes movies enough to review them for a living.

Brody wants everything in Perfect Days to be revealed, including (especially?) our protagonist’s politics. I mean, sure, how can we know what we’re supposed to think about another human being unless we know what their politics are? The idea that Hirayama might be utterly apolitical is one that seems not to have crossed Brody’s mind. Nor has he considered the artistic and moral possibilities of narrative reticence.

What’s wonderful about the movie is that it reveals just enough about Hirayama for us to understand that his simplified and repetitive life is both a comfort — a stabilizing power for a person who (for reasons only imperfectly glimpsed by us) desperately needs it — and also a kind of impoverishment. He is a lonely man who has many loose ties, which are unquestionably good things in his life, but no really strong ones, and we get a sense of what that lack of strong ties protects him from and what it deprives him of.

“Mama,” the woman who runs the little izakaya where Hirayama is a regular, wonders why everything can’t remain the same. Well, it can’t; but stability happens too. What we see at the end of Perfect Days is a kind of re-establishment of the rhythm of Hirayama’s life, but not without change, and not without the possibility of betterment. His new work partner seems to be a significant upgrade from the old one; his kindness to his niece Niko just might reconnect him to her and to his sister; and who knows, maybe he and “Mama” will forge the kind of relationship that he tells her ex-husband he doesn’t currently have with her. Change isn’t always bad. But a structured rhythm of life, a settled disinclination to chase novelty, an appreciation for what we can count on, including our friends the trees — that’s a very good thing indeed.

“The secret of good cursing lies in cadence, emphasis, and and antiphony. The basic themes are always the same. Conscious striving after variety is not to be encouraged, because it takes your mind off your cursing.“ – A. J. Liebling

I’m old enough to remember when I could say “Hey Siri, play [X]” and get the song I asked for.

Christian Spirituality: categories

The Great Texts program here at Baylor, where I teach about half my classes, begins its course of study with a series of periods: Ancient, Medieval, Early Modern, Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, Twentieth Century. Then it diverges into genres, themes, and topics. I’ve just concluded teaching Great Texts in Christian Spirituality — for the third time — and while that’s a very interesting and enjoyable course for me to teach, it’s quite a challenge to design. There are so many texts to choose from that (I tell my class) I could probably teach it five times with five completely different sets of texts and do equal justice to the theme.

And, of course, it’s very difficult simply to define the topic. What is Christian spirituality, for heaven’s sake? I always start with this: Christian spirituality is the application of Christian theology to the challenge of living — and then we work through various other definitions as the term goes on. But the boundaries between spirituality and theology never can become precise, and indeed, some key Christian thinkers would deny the distinction. As Jaroslav Pelikan has noted,

It was in the aftermath of the Council of Chalcedon that Maximus Confessor attained his historic importance, both for the history of spirituality and for the history of dogma (a distinction that he would not have accepted since, as every one of these treatises makes abundantly clear, there was for him no spirituality apart from dogma, and no dogma apart from spirituality).

Anyway: when I’m choosing texts, I’m careful to (a) cover the historical ground as best I can and (b) draw upon the three major streams of Christian writing on spirituality: Roman, Orthodox, Protestant. But over my three times teaching the course, I’ve come to think that certain other distinctions are important to acknowledge as well. I think especially of three axes:

- apophatic ↔ kataphatic

- individual ↔ communal

- encounter ↔ obedience

That is, any given Christian writer might emphasize the apophatic — what cannot be said about God and the experience of God — or the kataphatic — what can and must be said; might emphasize the individual or the communal and ecclesial aspects of the Christian life; might see the Christian life primarily in terms of an encounter with God or obedience to God. And you can sort Christian writers or texts accordingly. For instance:

- Julian of Norwich: apophatic/individual/encounter

- The Imitation of Christ: kataphatic/individual/obedience

- Eliot’s Four Quartets: apophatic/individual/encounter

- C. S. Lewis’s sermons and talks: kataphatic/communal/encounter

These classifications are arguable, of course! Also of course: they can’t be strictly distinguished from one another, for example, one’s obedience to God may have a great impact on one’s ability to have a genuine encounter with God. But as indicators of tendencies, as guides to emphasis, I think the categories are useful.

Some figures are difficult to classify: Maximus tends to cover all the possibilities, which is perhaps key to his uniquely powerful place in the whole tradition. (His Centuries are very much about communal life and obedience within that life, but he also wants to demonstrate the ways that an obedient life can lead to an encounter with the Divine that cannot easily be put into words.) But trying to place writers or books in this scheme has, in my experience, been a great way to generate conversation about them. Maybe some of you will find it useful.