Cory Doctorow: “AI companies are implicitly betting that their customers will buy AI for highly consequential automation, fire workers, and cause physical, mental and economic harm to their own customers as a result, somehow escaping liability for these harms. Early indicators are that this bet won’t pay off. Cruise, the ‘self-driving car’ startup that was just forced to pull its cars off the streets of San Francisco, pays 1.5 staffers to supervise every car on the road. In other words, their AI replaces a single low-waged driver with 1.5 more expensive remote supervisors – and their cars still kill people.”

You can’t just hate the present and long for the past, any more than you can make the future better by demanding of some nonexistent authority that they make it so. To make the future, you have to actually learn about the past, its glories and its follies alike, its conflicts and its contradictions. If we want to be like our forebears who successfully made it new, we have to, you know, be like them. We have to mine the incredibly rich resource of our past, and use that resource in whatever way we need to create new forms of art and politics, forms that are relevant to us. And then we have to hope that the future will treat us the same way, because then it will be alive.

Noah is absolutely right about this, because, you know, when is Noah not right? But I will just add that if you suggest that there is anything, anything at all, that we can learn from the past, a vast loud chorus will show up to shout: NOSTALGIA!

Adi Robertson: “As I’ve watched the Vision Pro go from announcement to release, it’s also seemed held back by something that has little to do with hardware. Apple is trying to create the computer of the future, but it’s doing so under the tech company mindset of the present: one obsessed with consolidation, closed ecosystems, and treating platforms as a zero-sum game.” Too true.

I’m going in.

On reading Horace: “In Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man James Joyce talks of the “human pages” of Stephen Dedalus’s ‘timeworn Horace’ that ‘never felt cold to the touch even when his own fingers were cold’. Many other readers have discovered in Horace’s poetry an intimate friend in the shape of a book. David Hume couldn’t look this friend in the eye when he was failing so abjectly to follow his advice.” I keep commending Horace, e.g. here. One of these days I’m gonna make him BIG!

Damon Krukowski: “If not Pitchfork, with more daily visitors than Vogue or Vanity Fair or the New Yorker - or GQ – then who in music journalism can possibly thrive in this economic environment. And if no one can… then all we’ll have left are streaming platforms, their algorithms, and the atomized consumer behavior they push on us.”

I deleted my micro.blog post on whether art makes us better people and replaced it with a somewhat longer one.

Effectual Art

David Brooks: “Does consuming art, music, literature and the rest of what we call culture make you a better person?” Answer:

- No. Consuming art can’t make anyone better.

- But experiencing art certainly can make you a better person.

- So can experiencing anything else. It depends on you.

But, okay, there’s more to say. Anything we experience may, depending on the circumstances, help to make us better people, but we have to be disposed to change, willing to change for the better. And maybe one thing art can do is to shape our dispositions, put us in a frame of mind or heart to live differently. (That’s what happened to Maggie Tulliver when she read The Imitation of Christ, which is not a work of art exactly but is a book artfully shaped.)

I still think one of the most useful approaches to this whole set of questions is Nick Wolterstorff’s early book Art in Action. Here’s a quote:

What then is art for? What purpose underlies this human universal?

One of my fundamental theses is that this question, so often posed, must be rejected rather than answered. The question assumes that there is such a thing as the purpose of art. That assumption is false. There is no purpose which art serves, nor any which it is intended to serve. Art plays and is meant to play an enormous diversity of roles in human life. Works of art are instruments by which we perform such diverse actions as praising our great men and expressing our grief, evoking emotion and communicating knowledge. Works of art are objects of such actions as contemplation for the sake of delight. Works of art are accompaniments for such actions as hoeing cotton and rocking infants. Works of art are background for such actions as eating meals and walking through airports.

Works of art equip us for action. And the range of actions for which they equip us is very nearly as broad as the range of human action itself. The purposes of art are the purposes of life.

I think these statements provide a great entry into the conversation about what art does and is, because they make the notion of “becoming a better person” less abstract. A mother whose lullaby soothes her baby and also calms herself is, perhaps, making herself a better person in that context, at that moment.

As a kind of pendant to my previous post, I comment to you this by Adam Roberts, which I thought of as I was writing:

When I was a kid I memorised — don’t laugh — the Bene Gesserit ‘Litany Against Fear’, and used to repeat it quietly to myself when I was in a place of terror. I was eleven or twelve, and my family had moved to Canterbury in Kent, from London SE23. Where we lived was about a mile’s walk into town, and the only way was down the narrow pavement alongside the Dover Road, on which enormous lorries and trucks would hurtle at incredible, terrifying speeds, on their ways to and from the port at Dover and London town — nowadays the city has built a ring-road to relieve its city centre of this burden of traffic, but that postdates me. Walking along this road as these T.I.R’s roared and howled inches from me was scary. Repeating the litany helped me cope with that fear.

I mean, sure: by all means laugh at me if you like … I was a massive SF nerd, not skilled at making friends, quite inward and withdrawn. I can see this little story has its ridiculous side. Then again, if I’m honest, when I look back at my younger self I find something touching and even, in its miniscule way, heroic about it, actually. I made it into town. I went to the Albion bookshop and spent my pocket-money on yet another pulp SF book. I got home again without being swallowed or consumed by my fear, although the fear, which perhaps looks trivial to you, was, inside me, vast and pressing and lupine, and was given prodigious materiality by the howling hundred-ton trucks speeding inches past me and whipping their trailing winds about me. I wasn’t really scared of the lorries; the lorries only gave temporary physical shape to something more pervasively in me and my relationship to life. I was a much and deeply frightened kid, as, in many ways, I still am, as an adult. Stories for kids should be beautiful and moving, but they should also furnish kids with the psychological wherewithal to understand and navigate the world and their own feelings about it.

Maggie and her Books

There’s a really extraordinary moment in George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss, a moment that says something profound about what we might call the ecology of reading in the age of print.

First, some background: Mr. Tulliver – the father of Tom and Maggie Tulliver, the two central characters in this novel – embarks upon a rash lawsuit which fails, and its failure sends him into bankruptcy. His family lose almost everything. As they are trying to adjust to their economic and social fall, Tom Tulliver receives a visit from his childhood friend Bob Jakin. Bob is a packman, a kind of traveling salesman who goes about on foot bearing a pack full of random goods which he sells mainly to the working poor. Bob is little better than working poor himself, even if through diligence and shrewd bargaining he is rising in the world: certainly he is constantly aware of his social inferiority to the Tullivers, despite their distressed circumstances; he always refers to Tom as “Master Tom.” Bob visits to try to give the Tullivers some money which Tom’s pride will not allow him to receive (probably he wouldn’t receive it from anybody, but he certainly won’t receive it from Bob). During their visit Tom’s younger sister Maggie comes in to the parlor and discovers that in the recent auction of their goods her books had been sold. Her eyes fill with tears; she is especially grieved over the loss of the family copy of The Pilgrim’s Progress: “I thought we should never part with that while we lived.”

Maggie is a devoted reader, much more so than her brother, and earlier in the book, when Maggie visits Tom at the pastor’s house where he is a paying pupil, we see that her intellectual interests are far stronger than his own and her capabilities far greater. But this was not an era in which young women of such gifts were reliably provided with an education adequate to them, so Maggie must remain largely self-educated. Thus she treasures so greatly the handful of books she owns and is so grieved at their disappearance.

Bob, who adores Maggie, though as a creature far above him in the Great Chain of Being, notices her distress and some weeks later pays her another visit. He has brought with him some books that he has scavenged in the course of his labors. Some of them are illustrated books – Bob himself thinks the illustrations quite fine and likely to interest Maggie – but he’s also aware that Maggie likes books with words in them and so makes sure to bring her a parcel of those: “I thought you might like a bit more print as well as the picturs, an’ I got these for a sayso, – they’re cram-full o’ print, an’ I thought they’d do no harm comin’ along wi’ these bettermost books.” (Bob, being illiterate, can’t tell you anything about the content of the books, he can only judge quantity of print.) Maggie receives these gifts gratefully but sets them aside; she has much on her mind and it’s not until later that she thinks to take up one of the volumes.

She does so at a time of great personal and familial distress. She has been forced to leave school — where she had been learning at least a few rudimentary skills that a young woman might need — in order to tend to her father, who has collapsed in the aftermath of his financial defeat and its consequent shame. All her life now is caring for her father’s needs, but she is a teenage girl of high intellect and great passion, and the consumption of her whole being in the dreary round of daily service is of course a struggle to her. Among the books in Bob’s parcel, the one that catches her eye is an old translation of Thomas a Kempis’s The Imitation of Christ. She feels that she has heard the name but knows nothing about the book; she picks it up and begins to read.

And here is where something extraordinary happens.

She took up the little, old, clumsy book with some curiosity; it had the corners turned down in many places, and some hand, now forever quiet, had made at certain passages strong pen-and-ink marks, long since browned by time. Maggie turned from leaf to leaf, and read where the quiet hand pointed: “Know that the love of thyself doth hurt thee more than anything in the world…. If thou seekest this or that, and wouldst be here or there to enjoy thy own will and pleasure, thou shalt never be quiet nor free from care; for in everything somewhat will be wanting, and in every place there will be some that will cross thee…. Both above and below, which way soever thou dost turn thee, everywhere thou shalt find the Cross; and everywhere of necessity thou must have patience, if thou wilt have inward peace, and enjoy an everlasting crown…. If thou desirest to mount unto this height, thou must set out courageously, and lay the axe to the root, that thou mayest pluck up and destroy that hidden inordinate inclination to thyself, and unto all private and earthly good. On this sin, that a man inordinately loveth himself, almost all dependeth, whatsoever is thoroughly to be overcome; which evil being once overcome and subdued, there will presently ensue great peace and tranquillity…. It is but little thou sufferest in comparison of them that have suffered so much, were so strongly tempted, so grievously afflicted, so many ways tried and exercised. Thou oughtest therefore to call to mind the more heavy sufferings of others, that thou mayest the easier bear thy little adversities. And if they seem not little unto thee, beware lest thy impatience be the cause thereof…. Blessed are those ears that receive the whispers of the divine voice, and listen not to the whisperings of the world. Blessed are those ears which hearken not unto the voice which soundeth outwardly, but unto the Truth, which teacheth inwardly.”

The quiet hand – Eliot repeats the phrase: “She went on from one brown mark to another, where the quiet hand seemed to point, hardly conscious that she was reading, seeming rather to listen.” Her reading of this book becomes a kind of three-way conversation: this miserable adolescent girl in Lincolnshire, the old monk, and the long-dead reader whom Maggie thinks of as her “invisible teacher.”

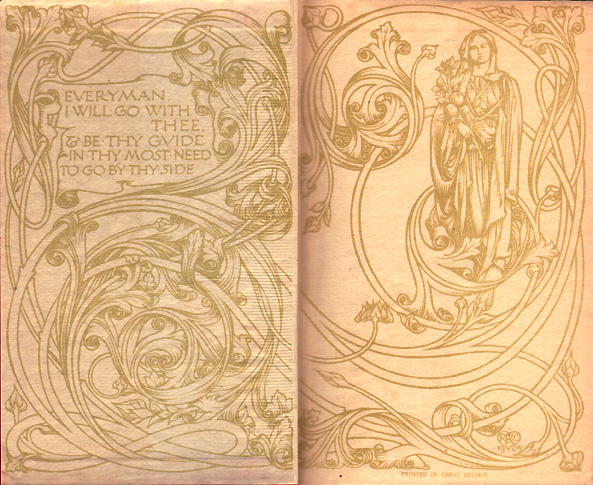

Maggie has been deprived of visible teachers, at least ones who would teach her the things that she most cares about, but here she finds one – in the margins of an old book picked up in some dingy provincial shop by an illiterate packman – who is able to guide her in her time of greatest distress. I find myself remembering here the motto of the Everyman’s Library editions, words that in the medieval morality play Everyman are spoken by Knowledge:

Everyman,

I will go with thee,

and be thy guide,

In thy most need

to go by thy side.

So the publisher, by gathering these great books together and making them both presentable and affordable, can become itself an “invisible teacher.”

By the time she wrote The Mill on the Floss, Eliot had (to my regret) left behind the evangelical piety that dominated her own teenage years; but that does not reduce her admiration of The Imitation of Christ:

I suppose that is the reason why the small old-fashioned book, for which you need only pay sixpence at a book-stall, works miracles to this day, turning bitter waters into sweetness; while expensive sermons and treatises, newly issued, leave all things as they were before. It was written down by a hand that waited for the heart’s prompting; it is the chronicle of a solitary, hidden anguish, struggle, trust, and triumph, not written on velvet cushions to teach endurance to those who are treading with bleeding feet on the stones. And so it remains to all time a lasting record of human needs and human consolations; the voice of a brother who, ages ago, felt and suffered and renounced, – in the cloister, perhaps, with serge gown and tonsured head, with much chanting and long fasts, and with a fashion of speech different from ours, – but under the same silent far-off heavens, and with the same passionate desires, the same strivings, the same failures, the same weariness.

That heartfelt and heart-prompted book was once found by a reader whose own heart responded to it; and he (or she) recorded that response with a pen; and that record, many years later, gave direction and comfort to a friendless and miserable girl in a small English town.

This idea of books and their readers as friends and teachers, as a silent fellowship extending across time and space, is a very dear one to me. Like Francis Spufford, I was a child that books built; in a childhood with its own deep unhappiness, books were my best companions and almost my only real teachers. And at a moment when our educational system is in such disarray, when it so often does ill rather than good to its students, it’s important to remember that these resources are available – and available in radically more extensive forms than Maggie Tulliver could have dreamed possible. The world of print, publication, and distribution holds together an ecology of reading, a vast circulatory system by which mind speaks to distant mind, and heart to distant heart.

That old copy of The Imitation of Christ and the invisible teacher within it guide Maggie through a great crisis in her life. Through them she learns the discipline of self-renunciation, and while she later comes to question – is forced by a man who loves her to question – whether self-renunciation is indeed her call, there is no question that what she learned from that book truly saves her in that crisis. And she never wholly forgets what she learned in that season of life, through the book’s text and through the patient directions of the quiet hand.

The lessons of the old monk and the invisible teacher might have been valuable to her much later in life, had she been granted a long life. But that is a longer and a darker story, one that I will take up elsewhere.

A scholar named Isaac Waisberg has put together a vast collection of translations of Horace into English. This is quite interesting to me because Horace does not go easily into English: he can be both casual and concise, and English finds it hard to be both at once.

I’m really pleased that the new AppleTV series Masters of the Air features a portrayal of Robert “Rosie” Rosenthal, who ought to be, but is not, one of the most famous American military heroes. A bomber pilot of unmatched skill and unmatched courage, he received every imaginable medal from the United States, Great Britain, and France. After the war he resumed his career as a lawyer — as a member of the legal staff for the Nuremberg Trials, in which capacity he interrogated Hermann Göring. Later in life, responding to the rumor that he had fought so fiercely because he had relatives in Nazi concentration camps, he said, “That was a lot of hooey. I have no personal reasons. Everything I’ve done or hope to do is because I hate persecution. A human being has to look out for other human beings or there’s no civilization.”

a small parable

Occasionally I find myself in groups populated by business people, technologists, consultants, people who work in nonprofits, practitioners of various kinds — and academics. Such groups gather to figure out how to respond to certain major social problems. Because the participants come from various professional worlds, it can sometimes be difficult to discover a common language, but one theme is always quickly settled on: It’s totally fine to talk about how useless academics are — especially academics in the humanities.

I’ve experienced this so many times over the years that I have to make a point of reminding myself of how curious it is. I mean, why invite people to a gathering only to tell them that they have no contribution to make? But I never respond to the dismissal and mockery; I just sit there and smile. I am only tempted to reply in one situation: When people say that academics “have their heads in the clouds.” Or that we humanists are always taking “the view from 50,000 feet.” That’s when I want to say: No. We’re not taking the view from 50,000 feet, we’re taking the view from ten feet underground, and from long long ago.

Once there was a man named Jack who owned a nice house. One day, though, Jack noticed that one end of the house was a little lower than it had been. You could place a ball on the floor and it would slowly roll towards that end. Jack was a practical man, so he called Neil, another practical man he knew, who worked in construction. Neil said that he could jack up that end of the house and make everything level again. Jack agreed, and Neil got to work.

Jack had a neighbor named Hugh. Hugh was interested in many things, and watched closely as Neil jacked up the low end of the house. With Jack’s permission, he looked around the basement of the house. All this made him more curious, so he walked down to the town’s Records Office and got some information about Jack’s house: when it had been built, who had built it, and what the land had been used for before. Hugh also learned a few things about the soil composition in their neighborhood and its geological character.

Hugh paid Jack a visit so he could tell Jack about all he had learned. He stood at Jack’s door with his hands full of documents and photographs, and rang the bell. But when Jack answered he told Hugh that he didn’t have time to look at documents and photographs. He had a very immediate problem: that end of his house was sinking again. In such circumstances Jack certainly couldn’t attend to Hugh’s ragbag of information and discourses about ancient history. After all, Jack was a practical man.

Tyler Austin Harper: “The first step is refusing to indulge in certainty, the fiction that the future is foretold. There is a perverse comfort to dystopian thinking. The conviction that catastrophe is baked in relieves us of the moral obligation to act. But as the extinction panic of the 1920s shows us, action is possible, and these panics can recede.”

a note on plagiarism

The Claudine Gay plagiarism scandal — or, depending on your point of view, “plagiarism” scandal — has me thinking about How We Write Today. John McWhorter has recently written that there really is a meaningful distinction between plagiarism and “duplicative language,” and I suppose there often is, but it’s all because of technology, innit?

That distinction arises because of what people do when they read as well as write on a computer. “Duplicative language” arises when scholars (presumably in something of a hurry) see something in a digital book or article that they want to use, copy the relevant text, and then paste it into Word with the intention of editing it later to in some sense make it their own. (Part of McWhorter’s argument is that maybe we don’t need to do that, or do it as often. I don’t think I agree, but I’ll waive the point for now.)

At least some of these issues arise from a general sense that one’s work should not contain too many long quotations, an idea that Adam Roberts has explored and questioned here. (I might disagree with Adam also, but I’ll waive that point as well as McWhorter’s.) The tendency to overquote becomes a problem when professors don’t have a lot to add to an existing scholarly conversation but need publications for tenure or promotion. In such circumstances, the bulk of any given article will likely be the collecting of other scholars’ work, and if you quote too much, it might become obvious that there’s not a lot of you in your article. So you need to rework the quotations to make the extent of your debts less obvious.

But note that all of this is a result of the pressure to publish, a pressure that people might feel especially strongly if their stronger interests are in teaching or administrating. That Claudine Gay has never written a book, and has produced only eleven journal articles in twenty years, one of those co-authored, and moreover moved quite early in her career into administration, all suggests that we’re dealing here with a person whose primary calling is not the production of scholarship. And that’s totally fine! By all accounts Gay has been an effective administrator, and Lord knows academia needs more of those. Heck, maybe Gay even has some scholarly humility, something I have heard of, occasionally.

So if you’re a person who is publishing under pressure, and not really extending the scholarly conversation in dramatic ways, and perhaps not even very excited about writing, then you’ll probably be more prone to (a) copy and paste that digital text and (b) forget later to make the necessary changes.

I don’t think I do this? I hesitate to assert too strongly, because I may be deficient in self-knowledge. But I will say this: whenever I copy and paste from some existing text, primary source or secondary, I paste it as a quotation. I never ever paste it into the body of my work. When I’m drafting an essay or article or book chapter I just don’t worry about whether I have too many quotations or whether the quotations are too long. That’s something I assess in revision.

Which makes me wonder whether some of the plagiarism (or “duplicative language") we’re now seeing so much of is a result of one small habit common to digital writing: pasting wrongly. Pasting as body text and not as quotation. Maybe this should be part of what we teach our student writers: If you think you can just drop a quotation into the body of your text and and then go back to fix it later, you’re may well be fooling yourself.