Quanta Magazine interview with Leslie Lamport:

One last thing, about another side project of yours with a sizable impact: LaTeX. I’d like to finally clear something up with the creator. Is it pronounced LAH-tekh or LAY-tekh?

Any way you want. I don’t advise spending very much time thinking about it.

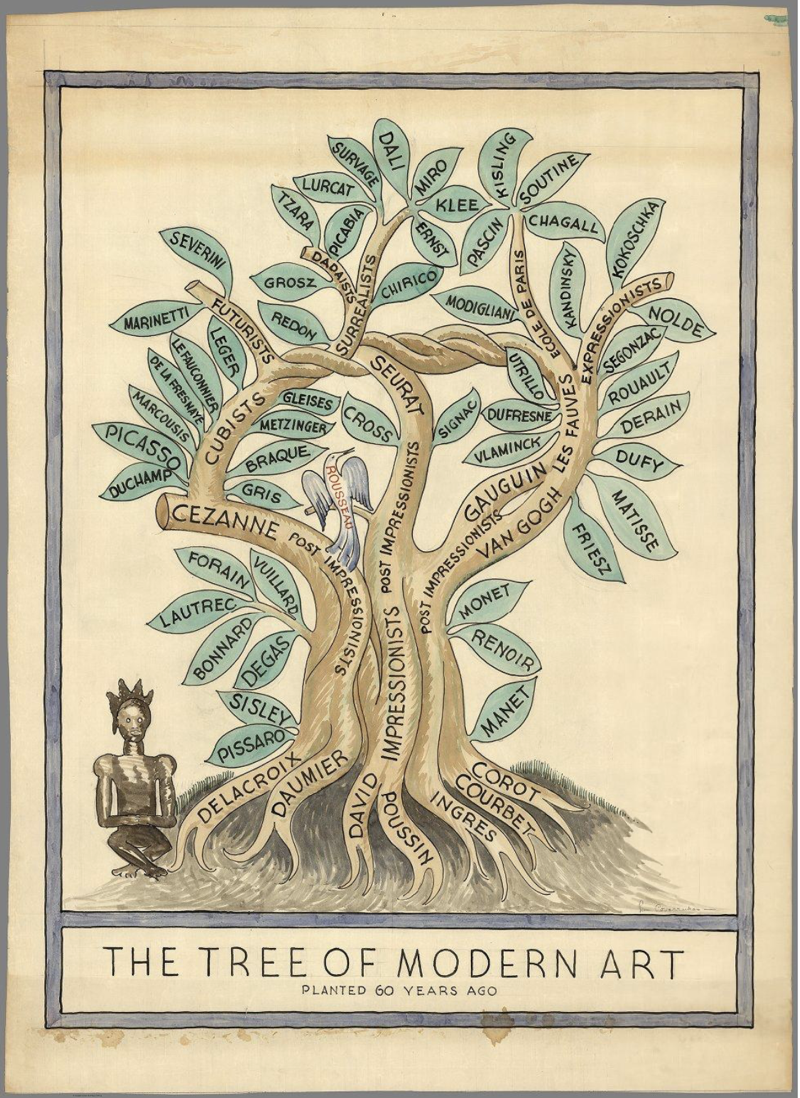

By accident of birth I am a modern, which means I will never know a charmed world. A world of consecrated hosts and faerie-haunted forests, where the line between individual agency and impersonal force is blurred at best. Gone is the idea of a porous human self, vulnerable to immaterial forces beyond his control. Significance has retreated from the outer world into our respective skulls, where, over time, it has stiffened, bloated, and finally decomposed into nothing, into dust.

This decay of faith — in institutions, in other people — is practically audible to me. I exist within a purely immanent culture in which the value of human life has been reduced to the parameters of the marketplace, where little is sacred and even less is profane. And I cannot take this shit much longer, I said.

So he started getting to know a man who says he can summon demons. An extraordinary essay. For context, I would — with all due humility — suggest that you read two pieces by me:

I very much enjoyed the recent Rest Is History podcast episode on Agatha Christie — and if you did too, you might be interested in this essay of mine. I don’t think many people have ever read it, but it’s one I especially enjoyed writing, and the New Atlantis editors supplied some illuminating images. Give both the podcast and the essay a try, please!

The Incapable States of America? – Helen Dale:

State capacity is a term drawn from economic history and development economics. It refers to a government’s ability to achieve policy goals in reference to specific aims, collect taxes, uphold law and order, and provide public goods. Its absence at the extremes is terrifying, and often used to illustrate things like “fragile states” or “failed states.” However, denoting calamitous governance in the developing world is not its only value. State capacity allows one to draw distinctions at varying levels of granularity between developed countries, and is especially salient when it comes to healthcare, policing, and immigration. It has a knock-on effect in the private sector, too, as business responds to government in administrative kind.

Think, for example, of Covid-19. The most reliable metric — if you wish to compare different countries’ responses to the pandemic — is excess deaths per 100,000 people over the relevant period. […]

The US has the worst excess death rate in the developed world (140 per 100,000). Australia has the best: -28 per 100,000. Yes, you read that right. Australia increased its life expectancy and general population health during the pandemic. So did Japan, albeit less dramatically. The rest of the developed world falls in between those two extremes: Italy and Germany are on 133 and 116 per 100,000 respectively, with the UK (109 per 100,000) doing a bit better. France and Sweden knocked it out of the park (63 and 56 per 100,000 excess deaths).

Dale’s takeaway: “Americans are individually charming and pleasant people who deploy their wits to get around a state that doesn’t work.”

pandemic and biopower

"Permanent Pandemic," by Justin E. H. Smith:

When I say the regime, I do not mean the French government or the U.S. government or any particular government or organization. I mean the global order that has emerged over the past, say, fifteen years, for which COVID-19 served more as the great leap forward than as the revolution itself. The new regime is as much a technological regime as it is a pandemic regime. It has as much to do with apps and trackers, and governmental and corporate interests in controlling them, as it does with viruses and aerosols and nasal swabs. Fluids and microbes combined with touchscreens and lithium batteries to form a vast apparatus of control, which will almost certainly survive beyond the end date of any epidemiological rationale for the state of exception that began in early 2020.

The last great regime change happened after September 11, 2001, when terrorism and the pretext of its prevention began to reshape the contours of our public life. Of course, terrorism really does happen, yet the complex system of shoe removal, carry-on liquid rules, and all the other practices of twenty-first-century air travel long ago took on a reality of its own, sustaining itself quite apart from its efficacy in deterring attacks in the form of a massive jobs program for TSA agents and a gold mine of new entrepreneurial opportunities for vendors of travel-size toothpaste and antacids. The new regime might appropriately be imagined as an echo of the state of emergency that became permanent after 9/11, but now extended to the entirety of our social lives, rather than simply airports and other targets of potential terrorist interest.

An absolutely brilliant, disturbing, essential essay — to be considered in light of certain reflections by Giorgio Agamben. From later in the essay:

There is no question that changes of norms in Western countries since the beginning of the pandemic have given rise to a form of life plainly convergent with the Chinese model. Again, it might take more time to get there, and when we arrive, we might find that a subset of people are still enjoying themselves in a way they take to be an expression of freedom. But all this is spin, and what is occurring in both cases, the liberal-democratic and the overtly authoritarian alike, is the same: a transition to digitally and al- gorithmically calculated social credit, and the demise of most forms of community life outside the lens of the state and its corporate subcontractors.

I’m annotating this in detail — and by the by, there ought to be a better way for me to share my annotations. You can do some cool stuff with Hypothesis, but not all the things I want and need. Maybe more on those wants and needs in another post, but for now, back to my PDF of Smith’s terrific essay.

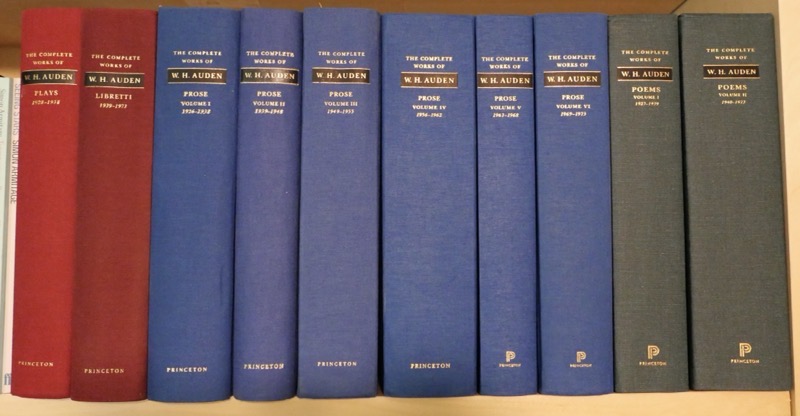

These beauties arrived:

So now the set is complete:

Had to do my review from PDFs, so this seems my just reward.

Finished reading: Anarchy and Christianity by Jacques Ellul 📚

Writing for a notional audience — particularly an audience of strangers — demands a comprehensive account that I rarely muster when I’m taking notes for myself. I am much better at kidding myself my ability to interpret my notes at a later date than I am at convincing myself that anyone else will be able to make heads or tails of them. […]I like this post very much — and especially Doctorow’s idea of a blog as a place to make your commonplace book public. I hesitate to go all-in with this approach simply because I don’t want to overwhelm my readers with stuff.Blogging isn’t just a way to organize your research — it’s a way to do research for a book or essay or story or speech you don’t even know you want to write yet. It’s a way to discover what your future books and essays and stories and speeches will be about.

I’m trying it out, but this is my fifth post today, which seems massively self-indulgent. On the other hand, it is rather odd for me to have two separate collections of notes, one on my computer and one on my blog.

notes

Interesting convo at micro.blog about what people use to take notes. Me?

- Handwriting in notebooks (usually Leuchtturm)

- Marginal commentary and sticky notes in books

- Voice notes in .mp3 format (the plain text of audio)

- Plain text notes on the computer

I want my notes to be future-proof and platform-agnostic.

For what it may be worth: As the years go by my opinion of OK Computer ascends and my opinion of Kid A descends.

welp

More than twenty years ago Malcolm Gladwell published a fascinating essay about two different modes of failure in sports: panicking and choking. “Panic … is the opposite of choking. Choking is about thinking too much. Panic is about thinking too little. Choking is about loss of instinct. Panic is reversion to instinct. They may look the same, but they are worlds apart.” Over the past decade, Arsenal have become masters of both modes of failure. When a player flies into a late tackle or drags down an attacker, he’s panicking (hello Xhaka, hello Rob Holding), but what happened to the side yesterday was a unanimous collective choke: when they needed a solid performance, everyone became paralyzed.

Arsenal are like the Ship of Theseus: All the players change, all the front office people change, nothing is what it was a decade ago … except the panicking and choking. Those endure. It’s a mystery to me, but if you’re going to be an Arsenal supporter you have to learn to live with it, because it’s hard to imagine it changing — it’s part of the DNA of the club now.

I’d prefer to be a supporter of any other kind of club, but it’s difficult (I’m inclined to say impossible) to choose these things. You end up emotionally attached to a team for reasons unknown and probably unknowable. So I would drop Arsenal in a second if I could, and turn, not to a better club, but a less neurotic one. But I don’t think I can.

this is your brain on shuffle

Every morning — and I mean every single morning — when I awaken from slumbers, my brain serves up a song. A different song each day, as a rule. Never merely a chune, as the Scots fiddlers would say, but always a song with words, and usually a pop song from any time in the past fifty years. Rarely it's a hymn, and even more rarely a pre-Sixties pop song; but from within that fifty-year window it can be pretty much anything, including songs I haven’t thought of in years or even decades. A few times it’s been a theme song from an old TV show.

The only exceptions to the Random Shuffle Rule come when I’ve had a song on heavy playing rotation. For instance, last year when I was obsessed with Big Red Machine’s gorgeous “Phoenix” it became my morning song on several occasions. But typically what turns up as I lift my head from the pillow is a surprise and I love that.

This morning it was “Gates of the West” (a neglected little gem, that one); yesterday it was “Mykonos”; and that’s all I’m going to say. I’ve never actually written or (except to my family) spoken about this oddity of mine, and I’ve never made a record of the songs — I’m superstitiously afraid that any such documentation will put an end to the service. So this post is as far as I’m willing to go in self-revelation.

But I mention it because I wonder how many other people have something like it — a central element of daily experience that no one else (or hardly anyone) knows about. Some quirk, some habit, whatever; but something that for you is a major feature of life even though no one would have any way of knowing it.

Currently reading: The Moving Finger by Agatha Christie 📚

Currently reading: The Recognitions by William Gaddis 📚

reification and metaphysical capitalism

I’ve written occasionally here about what I call “metaphysical capitalism” — see the relevant tag at the bottom of this post — but one thing I have neglected to note is that one of the most powerful elements of the Marxist critique of capitalism has been the argument that it is the nature of modern capitalism to extend its understanding of the world into the personal, the emotional, the spiritual — in general the metaphysical realm.

A key text here is George Lukács’s famous essay on “Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat,” where he writes of “the split between the worker’s labour-power and his personality, its metamorphosis into a thing, an object that he sells on the market.” This happens in varying ways in the varying professions of the capitalism world; for instance, in any bureaucracy:

The specific type of bureaucratic ‘conscientiousness’ and impartiality, the individual bureaucrat’s inevitable total subjection to a system of relations between the things to which he is exposed, the idea that it is precisely his ‘honour’ and his ‘sense of responsibility’ that exact this total submission all this points to the fact that the division of labour which in the case of Taylorism invaded the psyche, here invades the realm of ethics.

And when Taylorism conquers both the psyche and ethics, we get self-Taylorizing — the complete internalization of metaphysical capitalism and the consequent redescription of a condition of enslavement as a condition of self-making. People come to believe that they’re expressing themselves on social media when in fact they’re doing Mark Zuckerberg’s bidding for free. They’re like Eloi thinking that they’re the masters of the Morlocks when in fact they’re merely food.

What I found especially interesting in my re-read of Lukács (for the first time in many years) is his demonstration that this commodification of the human person goes back a long way, much longer than we might typically think. For instance, he notes that in the Metaphysics of Morals (1797) Kant defines sex and marriage in the most commodified way imaginable: “Sexual community is the reciprocal use made by one person of the sexual organs and faculties of another,” while marriage “is the union of two people of different sexes with a view to the mutual possession of each other’s sexual attributes for the duration of their lives.” Lukács comments, “This rationalisation of the world appears to be complete, it seems to penetrate the very depths of man’s physical and psychic nature.” It’s capitalism all the way down.

I am anything but a Marxist, but it’s important for me to realize (however belatedly) that some of my own recent arguments were anticipated by Marxist thinkers a hundred years ago. I should probably be making better use of that critique — if not of their suggestions for what should replace capitalism.

I was very interested in this Jonathan Malesic essay on how college students are or are not coping with the stresses of Covidtide. For what it’s worth — all such reports are anecdotal, but, despite what people say, the plural of anecdote is data, when there are enough anecdotes and they’re read with sufficient intelligence — my Honors College students have been much more like those at the University of Dallas than the ones at SMU, where Malesic teaches. I have been consistently surprised and gratified by how cheerfully and competently my students have navigated the various complexities of this era. Indeed, they’ve handled it all with considerably more grace than I have. I can’t be sure why they’ve managed so well, but I think it has something to do (in many cases anyway) with Christian formation and something also to do with the sense of community and common purpose fostered by Doug Henry, the Dean of the Honors College, and those support staff who work regularly with the students.